I think I know quite a lot of North Tyneside, where I live, very well, especially the parts east of Wallsend. The geographer in me (which, to be fair, is most of me) insists on learning, getting to know and mapping the places I visit, let alone the places I live. Mostly I know these streets and roads for driving and, closer to my North Shields home, for walking. I got to know many of local streets and roads pretty quickly when I first moved here (in 2011) as I had a newborn daughter who I walked and drove endlessly, to get her to sleep and to give me some time out of the house.

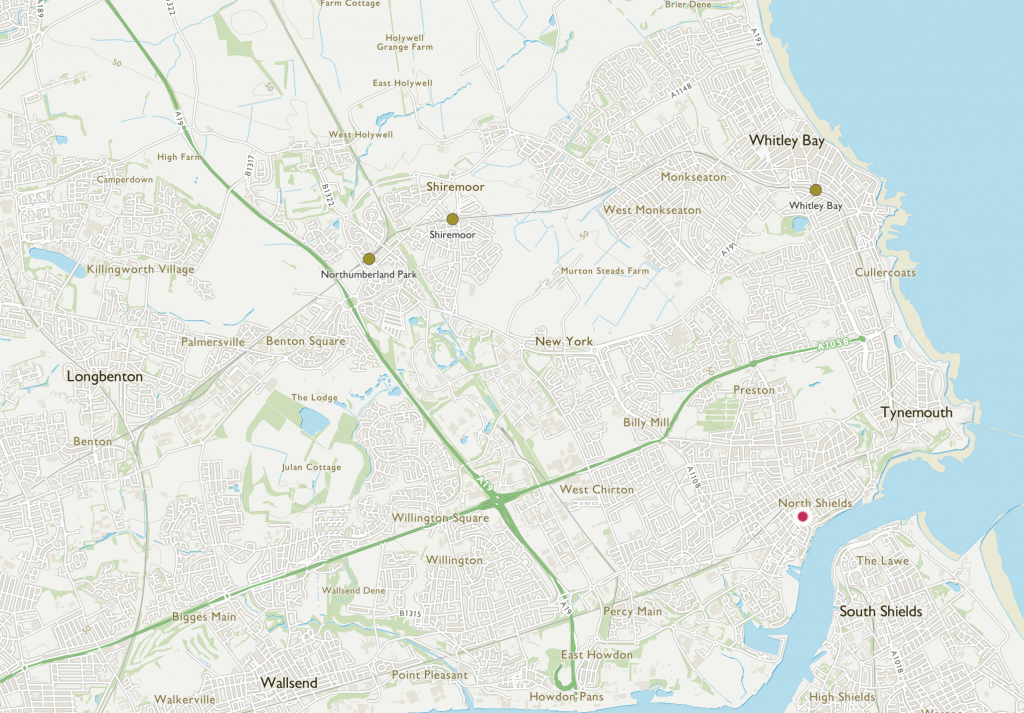

I drove west and north and round in circles, through Seaton Delaval, Seaton Sluice, Blyth, north to Northumberland (Cramlington, Morpeth) and south again through Killingworth and Forest Hall. Tha A19 and A1058 were my axes (the green lines on the map above) but I found other signed routes and used my instincts to always return a different way to my outward journey, making connections between places I was getting to know.

More often, I walked – up streets, through back alleys, finding snickets, new landmarks, with friends, on my way somewhere, or just to fill time. On these walks, I found the street we later moved to and the ‘secret garden’ where I now have an allotment. These walks created so many the ties I now have with my neighbourhood, brought me closer – step by step – to feeling at home here, marking my territory by beating the bounds.

From 2015, when we started to play out on my street, I started to make connections with other streets doing the same, with whom we had to share signs, passing them on from doorstep to doorstep on the morning of our street play sessions. And in 2017, I started to develop and coordinate playing out across the borough and got to know another layer of North Tyneside’s geography – working out whether streets could be closed, looking on Google Maps at terraces and semis, cross-streets, back alleys, and cul de sacs to see how easy and safe it would be to stop through traffic for a few hours a week, then delivering letters, notices and Road Closed signs to the growing number of streets that got involved, and finally beginning to see the patchwork of play streets connect across the borough.

So, I like to think I’m pretty well connected to North Tyneside, that I know its geography at a number of scales, that I think about where I’m going and make connections to the places I pass and travel to.

Yet, during successive lockdowns and the pandemic months, my connection to North Tyneside has grown, extending to new places and new perspectives, and deepened, as I’ve seen more in the places I know. I wrote here about how walking and scooting with my daughter in our closest streets fed an increasingly granular feeling of recognition and attachment, but as lockdown lifted, we filled the summer months with cycling and, for the first time, kayaking in and around the North Tyneside coast.

With and without my daughter, I’ve been cycling more and more – for fun and to visit friends along the Sunrise Cycleway, a 3-mile pop-up cycle lane created by North Tyneside Council in July (and ripped up in November), but also all around the coast, on all sorts of roads and paths, to shop and just to get around. My old bike died, I bought a new one, and now I’ve hired an ebike, to try it for a month. I’ve filled my ageing car up with petrol just 3 times in 9 months.

I was inspired to write this blog after my recent 23-mile bike ride, a carefully-planned round trip from North Shields to Battle Hill, Forest Hall, Killingworth, Backworth, Shiremoor, Wellfield, Monkseaton, Whitley Bay, Tynemouth and home to Shields. I spent a lot of time working out the route, asking advice, poring over Google Maps and Street View, weighing up the benefits of traffic-free routes against a fear of feeling scared. I was already developing a granular geography – seeing where there were alleyways to cut off a corner (or a few more metres on a busy road), spotting landmarks that would reassure me I was on track (primary schools, street names, the metro line, a pub or pizza takeway), and identifying places – roads, bridges, parks, paths – that I wasn’t sure I’d feel safe in. And, of course, I was connecting it to the places I already knew, from car and foot.

Heading out on Saturday morning marked the translation of this cartography of the mind and screen to a geography of body and bike, moving through these places I’d marked and memorised. At times, this meant realising that the short-cuts I’d planned on a screen took me up steep hills with sharp bends, or on narrow paths filled with families walking, or along rutted tracks and coarse gravel, or through an underpass in the earshot of the revving engines of micro bikes, that the physical, tangible geography of the real route was felt through my body – in exertion, in vibration, in anticipation and in fear. But it also meant that those bright, two-dimensional routes on screen translated into a short wooded path with a glorious soundtrack of birds and rustling leaves, a lakeside stretch fringed with reeds and new town houses, and a surprise level crossing with a warning to Stop Look Listen.

I was alert to the route, the traffic, and those with whom I shared my journey, for moments more or less brief. I observed and felt the surfaces, the potholes, the loose paving, the kerbs of different heights, the mud and the debris. I was grateful for smooth tarmac, alert to unavoidable ruts, looking ahead to see how I could navigate a turn or a crossing with the gentlest path for me and my bike. I noticed the speeds of cars, and roundels to warn me; I kept a constant eye on car doors and bends in the road, to expect the unexpected; and I looked for ways to avoid traffic if it came too fast and too close. I looked down and over my shoulder to be sure I could pull out, around a parked car or a pothole, if I needed to. I scanned ahead – and to the sides – for pedestrians, for children playing, and for dogs, tuning in for moments to witness their play, overhear their conversations, predict their next moves, at times ringing my bell, shouting a “thanks” or sharing an acknowledgement. And, at times, I listened to the voice on Google Maps telling me turn left, go straight ahead, make a u-turn.

I kept an eye out for those landmarks I’d recorded, to mark my progress and feel confident in my navigation, breathing a sigh of relief when the right path appeared or as I passed the school or shop I’d expected, and I tagged all these places on the maps in my head, to populate and animate my personal geography, and for the next time I travelled these routes. I also responded to the sites and sights that caught my attention, taking detours onto a path closer to the lake, or a road adjacent to the East Coast mainline and a speeding Pendolino, to check a noticeable street name, or take in a new housing development, to follow a path I suspected would lead me in the right direction. And I added all of these to those maps in my head.

And, of course, there were the wrong turns too, the bad choices, the moments of fear, a retracing of my steps, wasted time, a quick decision to get off and walk, or to move onto the pavement, to cross the road for more space or a better path. And each of these was accompanied by a calculation, a moment of self-criticism, of doubt and anxiety, of hesitation, felt in my body on a bike. And each was added to the maps in my head.

Some of this was bad infrastructure, a common theme in cycling narratives. There’s of course a sense of disappointment and frustration when a cycle lane appears and disappears within metres, or a painted bike directs you along a useless or impossible path, but bad infrastructure is also felt in the stops and starts, the dismounts, the endless decisions, and the continuous attention to the kerbs, the surfaces, the camber, the bends, the micro-topography of the streets and roads.

And, of course, there were the places I wanted to see – the Ryder and Yates 1967 British Gas Engineering Research Station, now North Tyneside Council’s Killingworth Site, the new town estates of Killingworth – its East and West Bailey and ‘garths’, the new-build estates of Backworth and Northumberland Park, the 1930s cycleway on Whitley Bay’s Links, and St Mary’s Lighthouse – a fairly eclectic mix of sights but ones which help me map and get to know North Tyneside’s many faces.

This is how you learn a route and a landscape. On a bike, you can’t progress without paying real attention to the details of the route, from the road names, to the landmarks, to the potholes and kerbs; this attention is essential, but it is also valuable. You have to see, listen, feel, and because you have to, you connect more. In contrast to travel by car, or even on foot, the route becomes richer, denser – more granular – every sense is invoked by the nature of your contact with the road and the route, a body on two wheels, propelling itself, in an in-between place between car and foot, between road and pavement, moving from one to the other.

These were mostly new places and new routes, but through their inscription in my head they’re mapped for the next time, not just these actual places – where to go, where to find something, how to get from A to B – but also a more general sense of what feels right when I’m riding my bike, and what I need to pay attention to.

The attention to place, at every scale, which I reflected on and recorded in this one trip plays out in more mundane ways in my everyday geographies. On those routes I travel regularly – to the shops, to friends, to the beach – I have mapped the breadth of the roads, the choice of paths, the pinch points, the steepness and camber, the changing surfaces, the worst potholes, the joyous stretches, the viewpoints, and I have felt them, in mind and body. As a ride, I map and re-map the spaces of my everyday life, making connections, feeling the places I move through, adding layers to my mental maps. I see what is possible and what is restricted. These inscribed geographies embed me in my everyday worlds and they ready me for my next trip, allowing me to see where to go and how to move as each day I find my way in North Tyneside.

Thank you. Lovely description of everything I see, feel, hear whilst cycling and route finding. Helping out at Bike4health makes me conscious of ‘can I safely lead children’ on this route. This makes it doubly difficult to find as safe route as a single bottleneck or fitted section can eliminate it.