Unlike so many of my hardworking colleagues who are rapidly having to ‘pivot’ to online teaching and support their students online through challenging personal and academic times, I’m currently on a Leverhulme Research Fellowship. This brief blog is my attempt to get my head round this and start to work out, in these new circumstances, what on earth I can do for the next six months (until I’m due back teaching).

With a focus on organised playing out sessions on residential streets, I’m supposed to thinking about the following questions:

- how play creates a potential space for new and creative relationships between neighbours of all ages

- how regular playing out intensifies children’s and adults’ connection to the objects and materialities of the street itself, through hanging out on and exploration of its kerbs, roads, pavements, trees, walls, and other affordances

- how the radical potential of play might open up debates around the place and value of relationships in our everyday lives;

- how these explorations around play and relationships map on to developing policy debates around community, loneliness, intergenerationality, and belonging.

In short, my work at the moment is focused on thinking about the relationships between play, neighbours and streets.

I received ethical approval for my fieldwork, to be based on observational and participatory research on streets across the UK, just as the coronavirus crisis hit, as universities withdrew support for all travel, and, then as the national lockdown was introduced. I can’t travel around the UK and streets will most likely not be playing out anyway, if they adhere to current guidance. So, I won’t be spending time on streets as they play out this spring and summer.

Yet, the relationships between play, neighbours and streets seem to be both all the more important and all the more complicated. As the coronavirus crisis and the lockdown have enforced new conditions for social contact, for the use of public space, and for the everyday lives of children and adults, my research questions seem both critical and almost impossible.

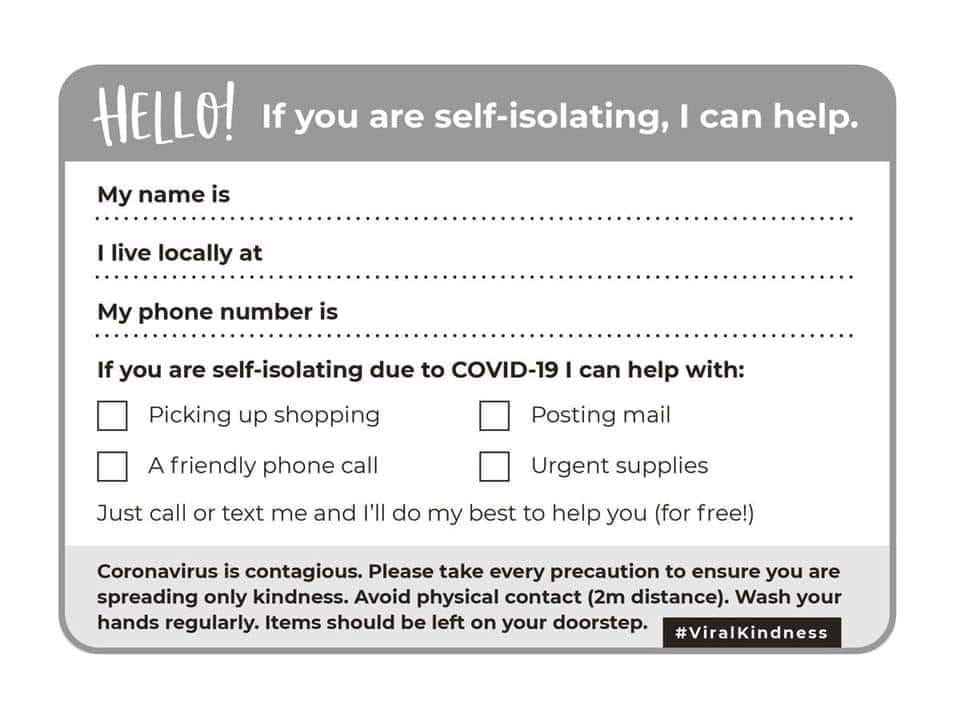

Of the many emergences in recent weeks, we have seen thousands of examples of neighbours connecting to support each other through notes distributed to letterboxes, through Facebook and WhatsApp groups, and through more formally organised mutual aid groups. This has happened on streets across the country (and of course elsewhere) but it certainly happened rapidly and fairly straightforwardly on streets that were already connected through play, where the intimate social infrastructures of neighbourhood connections already had names and faces attached. Our recent research on streets that play out found that an amazing 95% of respondents felt that they knew more people because of playing out sessions and 86.7% felt that their street felt friendlier and safer. We concluded that these connections support everyday contact and conviviality, friendships between adults and children, the exchange of help of all kinds, and a range of other neighbourhood activities, and we have seen these relationships develop and transform in recent weeks. But we also know, of course, that these connections are uneven and that they can be unwelcome and exclusionary, so there are many critical questions to be asked about this blossoming of neighbourhood support, its value, and its impacts.

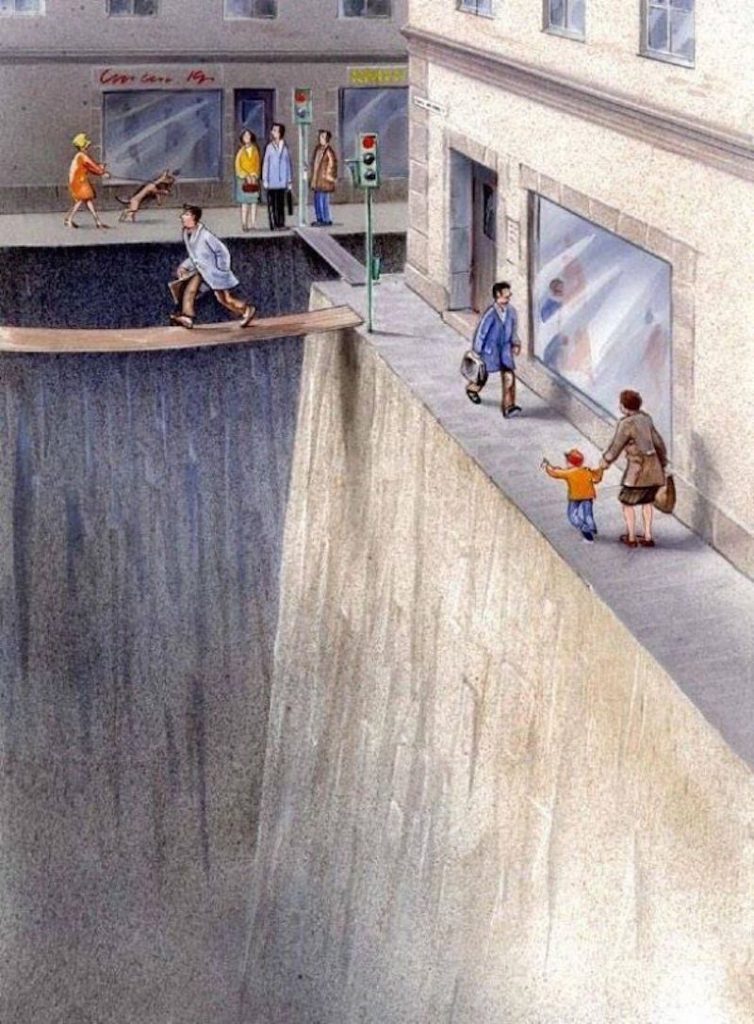

At the same time, our streets have been transformed by the restrictions of non-essential movement – car traffic has dropped enormously. The car has been parked, literally and metaphorically, and streets have quietened. In some places, there have been reports of speeding as the awkward few seek to take advantage of the situation, but in many instances, streets have been reclaimed by cyclists, families walking, to the shops or for exercise, runners, old and young, dog walkers, and children on scooters. The empty spaces of the street invite us to facilitate social distancing by using the whole of the street, not just its margins. In some ways, children and their families become paradoxically more visible on our streets, even in a time of lockdown, as they take their approved breaks from home-schooling to get daily fresh air and exercise. As I watch my street from my desk, most of the passers-by are parents with children, walking, running, scooting, cycling and in buggies. It is not like this in more normal times. Yet, the roads do still belong to cars and this remaking is both partial and precarious. Cycling and walking campaigners are increasingly asking that these changes be recognised and valued, as life eventually returns to normal, so that we can secure more permanently safer passage on our streets for pedestrians and cyclists. For those who dwell on streets – and especially children, families and the more vulnerable – we might also push harder the more challenging questions about how we could use street spaces better for all those who live and play on them and those who move through them, questions about who has the possibility and the right to spend time on and occupy our residential streets.

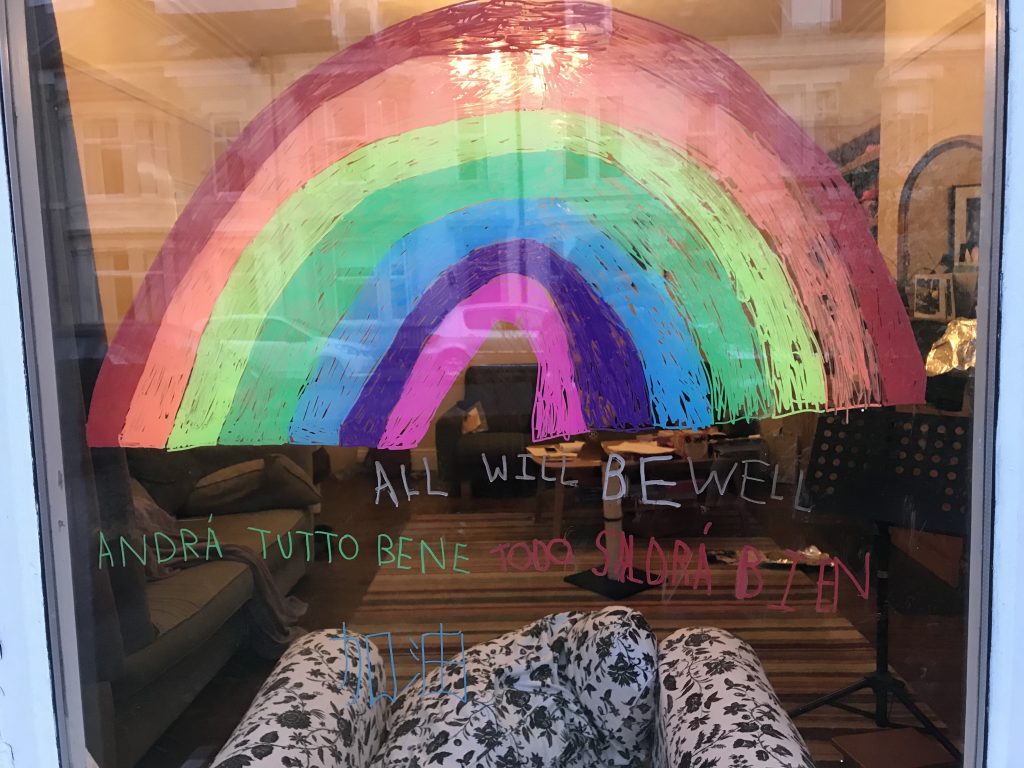

We also see a proliferation of playful acts between neighbours – from Italian and Spanish apartment residents singing in impromptu balcony choirs, to children’s painted rainbows appearing as signs of hope and developing into #rainbowtrails, to window bear hunts inspired by Michael Rosen, to hopscotch grids and other chalk art on pavements. The desire to connect through play – even at a distance – reflects the critical importance of play, for children and adults. As many play theorists have argued, we often make connections through play that we don’t make as easily otherwise. These acts then can be seen as evidence of our recognition that play facilitates connections and opens up new spaces for contact and for relationships. These acts would seem to be an attempt to remain social, to reach out, in a context where physically that is now extremely difficult. These playful signs, trails, sounds offer ways to hold a connection that is joyful and enlivening and that connects us as humans, even if we can rarely connect physically across the short distances that separate us. Those additional pedestrians, those families making the most of their time outside – who have space and time to linger and dawdle – stop to spot the rainbows or the teddy bears and make a brief, remote connection to their neighbours, perhaps also waving through the windows too. But we can also identify critiques of these acts – they’re superficial, gestural – like the #clapforNHS – and they perhaps do too little to really transform the spaces and relationships of our everyday lives. Their appeal is immediate but their value is as yet unclear.

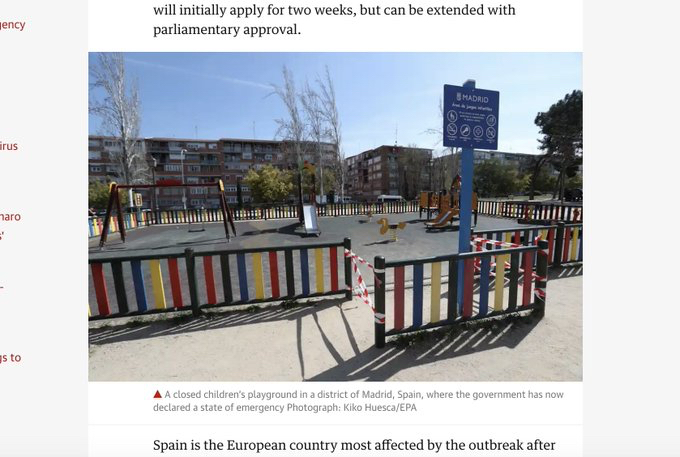

All these acts are all the more important as the spaces where we might otherwise connect and play are closed to us – schools, libraries, workplaces, each other’s homes, and, of course, playgrounds. Across the UK and beyond, playgrounds were one of the first casualties, as the social distancing guidance tightened, for fear of contact being too close and of contaminated swings and slides, as researchers evidenced the half-life of the coronavirus on different surfaces. The spaces and practices of outdoor play have been the subject of considerable debate amongst play activists since the crisis started, with a recognition that things could not continue as normal. Yet, there is also a recognition that space for outdoor play must somehow be protected, especially for those who do not have gardens, yards, or even balconies. As some municipal parks close for fear that social distancing isn’t being or can’t be maintained in such open, public spaces, others are calling for priority access to parks for children and their families. But what of our streets as spaces for play, especially in the context of falling traffic and their reclaiming by pedestrians and cyclists? Are there safe ways to advocate for outdoor play on our doorsteps that might alleviate some of the very real difficulties that a lockdown creates for families with children? And how might this rethinking challenge us again to reimagine where play takes place?

In all these myriad ways, my research questions are being brought into very sharp – but very different – focus. They are being refracted, reshaped, and challenged everyday, with new developments, new ideas and new practices. I am extraordinarily wary of attempting to capitalise on the covid crisis – but these questions of play, streets and neighbours are my job for the next six months. It would be utterly inappropriate too to ignore the changing circumstances and new challenges. How I refigure these questions in this context is a politically and personally difficult problem, complicated daily by the now more intense work of parenting and by the distractions and obstacles of life in a pandemic.