Please find below a list of some of the questions which were asked following the presentation with the answers.

What would have happened if Armstrong wasn’t here? Did he stop other people doing what he did?

Armstrong’s factory was described as the workshop of the world as it could make and supply warships as well as the modern ordnance to arm them. Armstrong was a successful inventor and industrialist, but he didn’t stop people doing what he was doing. For example, when he was designing the Armstrong Gun, his most serious rival was Manchester engineer Joseph Whitworth. The Ordnance Committee decided Armstrong’s guns were more accurate in 1858 and the Government signed a contract with them. Whitworth, however, continued to produce weapons and began to supply to foreign interests and built up an international market earlier than Elswick.

Similarly, Armstrong became interested in the advancement of shipbuilding in 1863 when he began to collaborate with Charles Mitchell at his Walker Yard. Charles Mitchell had been building ships for the Russian Navy since 1862. The first product of the collaboration between Armstrong and Mitchell was Staunch, a ‘floating gun carriage’. Staunch was ordered by the Admiralty, designed by George Rendel, built by Charles Mitchell and completed in 1868. Thus, war ships were already being built and designed on the Tyne before Armstrong’s interest and subsequent Shipbuilding Yard at Elswick.

You haven’t used any examples from British ships, was that deliberate?

This presentation focused on particular case studies from other countries which demonstrated the colonial ramification of the business. This is not a complete study of the Elswick Shipyard and all the ships produced there. It is more of an introduction to make people aware of this narrative and to create conversations to look at the business through a post colonial critique.

Armstrong’s shipbuilding company at Elswick produced over 30 ships for Britain, including 4 battleships. These Royal Navy ships, however, were often limited to training or patrol vessels and assigned to Home and the Grand Fleets. The battleships saw action in the Battle of Jutland and served in WW1.

Did Armstrong know Charles Parsons?

Yes, Charles Parsons began his career, after graduating, as an apprentice at the Elswick Works of Sir William Armstrong in 1877.

The Revolt of the Lash, has that been written up at all?

The Revolt of the Lash has one main published work by Zachary R. Morgan, Legacy of the Lash: Race and Corporal Punishment in the Brazilian Navy and the Atlantic World. Morgan provides a social and cultural history of the navy dating from the years preceding the abolishment of slavery through to the consequences of the Revolt and the legacy it left in Brazil. There are also different representations of the Revolt including “A Revolta da Chibata” which was presented as a stage play in Brazil in 1970. Also in 1974, a popular song about the Revolt was released with its lyrics originally censored.

Can you tell us a bit about the sources and research you used in this project?

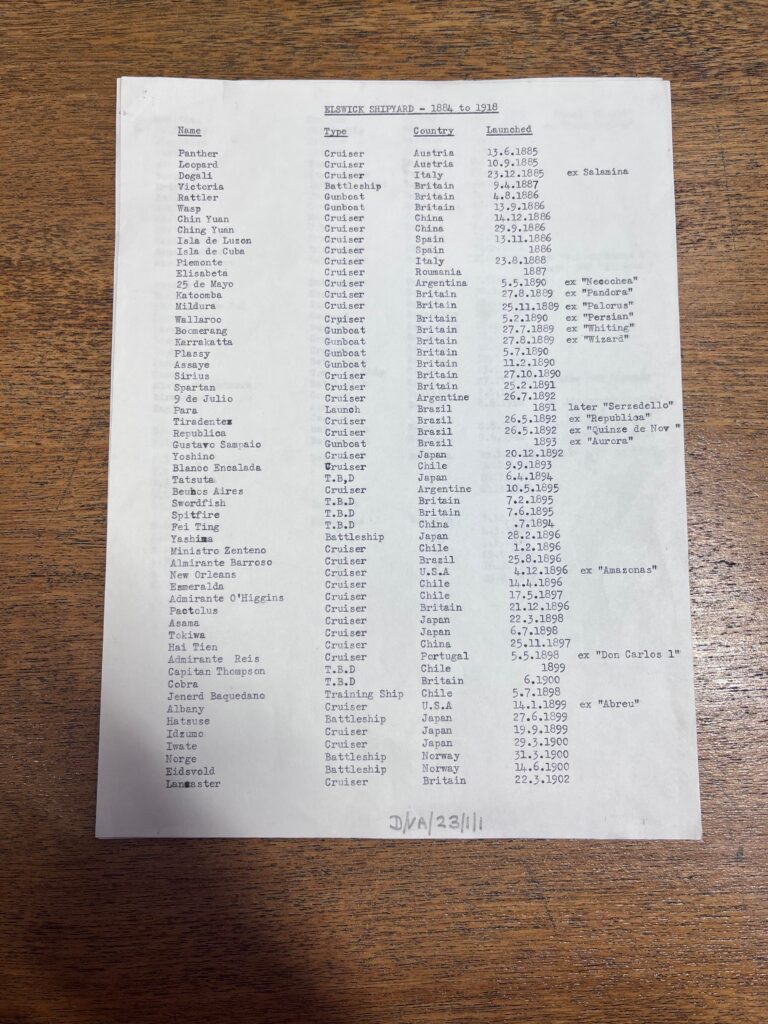

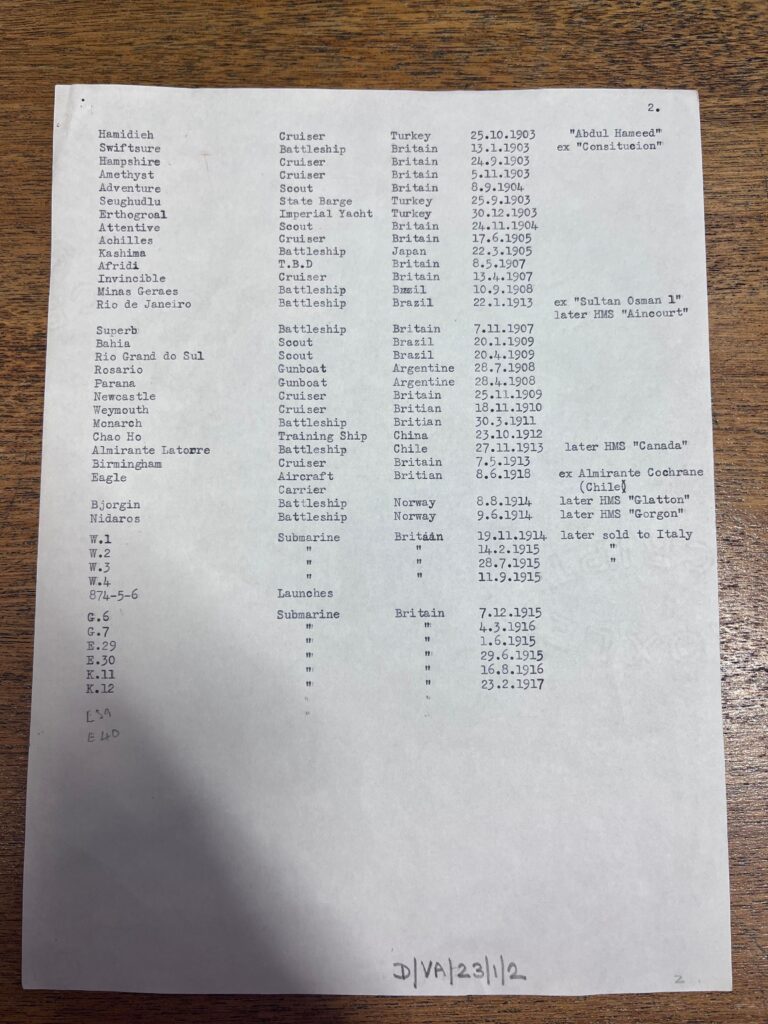

The Tyne and Wear Archives at the Discovery Museum were the start point of the research. After already researching Lord Armstrong I chose to look further into his shipbuilding business with a post colonial critique. The Tyne and Wear Archives have all the old company documents including inventory lists of the ships; launch cards for all the vessels; annual reports of the business and various images. I used a list of all the ships produced at Elswick and from there researched all the ships which a country had purchased in a case study manner. Secondary research, including books and websites, were used to follow the ships beyond their launch date. The Tyne Built Ships website has a detailed history of Tyne shipbuilders and the ships that they built, with images. I therefore also consulted this website for extra information on the ships built at Elswick.

Was he politically active in visiting and choosing which countries he built ships for or was it just to keep his business going?

Armstrong was not known for being very politically active in Britain or abroad. Whilst there are records of him travelling to a lot of the countries he sold ships to, Armstrong was more involved in the technological development and the overall direction of the firm. It was his directors, particularly Stuart Rendel who promoted Elswick’s reputation abroad and developed a worldwide network of agents and clients.

Which bit of the research did you enjoy most?

Researching the ships was a very long process however I did get excited when I found something interesting that the ships were involved in such as the Revolt of the Lash. I had never heard of this event before and finding out that so many Brazilian sailors had spent time in Newcastle and this had subsequently influenced their decision to revolt really highlighted the international scale of this local business. As a member of the Royal Navy Reserves myself the research also felt like it was coming full circle when I found out that HMS Calliope and the presence of the Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve on Tyneside started at Elswick.

Do you think part of the attraction of his ships was the size of his guns, the fact he was a gun maker?

I think this definitely helped. On the one hand he and his company at Elswick already had an international reputation, due to the client base the company had gained selling his guns. On the other hand, the fact that he could produce modern ships and also arm them with his ordnance meant the ships did not have to be sailed somewhere else to be armed before completion.

You talked about the shipyard bringing prosperity to Tyneside, do you know how many people were employed by the shipyard and whether their wages were good for the time?

In 1884, just before the shipyard was opened, the Elswick Works employed fewer than 5000 people. By 1897, after Armstrong bought Sir Joseph Whitworth’s Steel Company, he was employing more than 10,000 people on Tyneside. During the last decade of the 19th century, Armstrong’s periodically occupied first place in the league of British shipbuilders.

With regards to wages, I have not come across anything in my research about the wages of the workers and whether of not they were good for the time. It is an interesting question and another area of this topic which should be explored. Armstrong opened the Elswick Mechanics Institute which had specially equipped classrooms and a 500-seat lecture theatre as he believed passionately that education was the key to self-fulfilment and success in life. He also opened the Elswick Elementary School in 1866 for the workers families. However, on the other hand the workers at Elswick were involved in the 9 hour strike in August 1871, and Armstrong brought in foreign labour, rather than meet their demands.

What are people in Newcastle taught in schools now about the shipbuilding heritage? Is any of this mentioned, in that it was involved with colonialism and war, or is it all glossed over?

I personally am not from the North East and do not know what is currently taught in schools. I do know, however, that there are increased efforts to teach more local history in schools.

For example, we were involved in a local public history project run by Museums Northumberland on our MA course called Our Past Your Future. This website showcases the regions rich history of innovation in the fields of STEM through an interactive map. The map is constantly evolving as entries are added in partnership with communities companies and schools. Our Past Your Future is currently being used in 15 schools across Northumberland, North Tyneside and Newcastle to aid in the delivery of an intensive STEM learning programme.

There is also We Made Ships, a project of the Newcastle University Oral History Unit and Collective. We Made Ships focuses on the people who built the ships and what the shipyards were like for the people who worked there. This website brings together a wealth of local history projects and resources about shipbuilding, including photographs, videos and oral histories. These resources are presented in an easily accessible and interactive site, edited in consultation with secondary school teaching staff, to make it as useful as possible within schools.

However, unfortunately if the history of shipbuilding within the North East is taught in schools, I imagine in most cases, it is not from a post-colonial perspective.

Please find below a list of any references to publications or websites listed above.

Morgan, R. Zachary. Legacy of the Lash: race and corporal punishment in the Brazilian Navy. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2014.

Tyne and Wear Archives. View their catalogue at: https://twarchives.org.uk/.

Tyne Built Ships. “A history of Tyne shipbuilders and the ships that they built.” Accessed 9th August 2022. Available at: Tyne Built Ships & Shipbuilders.

Museums Northumberland. “Our Past Your Future.” Accessed 9th August 2022. Available at: https://museumsnorthumberland.org.uk/project/our-past-your-future/

We Made Ships. “Shipbuilding History in the North East.” Accessed 25th August 2022. Available at: Shipbuilding History in the North East (wemadeships.co.uk).