Who is this blog post for: Current or emerging middle leaders and for senior leaders or Headteachers who are developing middle leaders.

Author: Lisa Ramshaw

Posted on: 24th March 2023

Keywords: model; transformative; formal; collegial; political; subjective; ambiguity; cultural; goals; organisational structure

Introduction

This blog post shares a range of theoretical models that may help you recognise how your school or your educational organisation is structured and led.

Tony Bush is a leading educational theorist*, and he writes, “if practitioners shun theory, then they must rely on experience as a guide to action” (2020, p.20). As stated in the introduction to this blog series, we would like to create links between the theory, research, practice and reflection of leadership, whilst effectively utilizing case studies as an experiential component.

In the first reflection post of this series, it was prefaced that the two layers of the hierarchical structure can pull a middle leader in many directions; however, not all structures within an educational setting follow a particularly hierarchical model. This article aims to present six different theoretical models of educational management by Bush (2020), in order to provide different ways of viewing your institutional structure. Bush (2020, p.22) claims that “each theory has something to offer in explaining behaviour and events in educational institutions”.

Recently, I facilitated a seminar that focused on these educational models and a school leader said to me – “I understand my own institution and how things work but an understanding of these models has now allowed me to put a ‘name’ to it and therefore understand the school structures and processes more deeply than I did before. I also now know the educational model I would like the institution to move toward. I feel like I have clarity on the institution’s development now”.

So, let’s look at these models in more detail. In his book, Bush (2020) explains six educational models. Click the title below to view a summary of each model.

Six Educational models (click to expand)

| Formal | The formal model depicts the most common hierarchical model that most of us would recognise in institutional structures, where there are clear positions and accountability. |

| Collegial | Collegial models are more about a collaborative approach whereby people agree on goals / shared views of values, in a more lateral structure. People work together in a collaborative manner and leadership is usually distributed effectively. |

| Political | In a political model, processes of negotiation and bargaining are common, and interest groups develop and form alliances or coalitions in pursuit of particular objectives. At times, conflict can emerge, and different forms of power can be used, including positional power; authority of expertise; personal power; control of rewards; coercive power. |

| Subjective | In this model, there is more interest in processes and relationships and the organisational structure tends to be an outcome of the interaction between people. The individual participant is at the heart of the organisation and should not be regarded simply as a cog within the institution. |

| Ambiguity | In an ambiguous model, institutions are characterised by fragmentation and ‘loose coupling’ – i.e., sub-units operating autonomously. Rules and regulations are unclear or disregarded and participation in decision-making is fluid. |

| Cultural | In a cultural model, there is a close link between culture and structure, and values and beliefs are expressed in the pattern of roles which underpin attitudes and behaviours. There is a development of shared norms and meanings: the ‘way we do things around here’ and these are expressed through rituals and ceremonies which support the beliefs and norms. |

Figure 1: Six Educational Models (Bush, 2020).

Reflection (click to expand)

- What educational model do you think your institution reflects most based upon the above summary statements?

Now let’s reflect on each model a little more closely. The table in the drop-down section below sets out a number of reflective questions so that you can consider what model or models are most applicable within your context.

There is no hard and fast rule that only one model can be applicable to a particular context: there may be a combination of different models evident at any one time, based on the nature of the task or activity, so bear this in mind as you work through the reflective questions.

Reflective questions for each model (click to expand)

| Model | Organisational structure | Leadership | Goals |

| Formal | Is your institutional structure hierarchical and vertical? Are there clear role accountabilities? Is the structure defined by particular positions in the institution? | Do leaders operate through a top-down approach? Do you feel leaders are pragmatic and clearly divide labour to meet particular goals and tasks? | Are goals and direction set for you in the institution? Are there goals at multiple levels throughout the hierarchy? |

| Collegial | Is your institution structure lateral and horizontal? Do you feel there is an equal right to determine policy? | Is there authority of expertise, in that leadership is a collective endeavour, which may include peer leadership (for example) amongst teachers? Is leadership effectively distributed and shared? | Do staff agree on goals and have a shared view of values? Is there a collaborative approach to such agreements? |

| Political | Has your institutional structure emerged from a process of negotiation and bargaining? Have ‘interest groups’ developed and formed alliances or coalitions in pursuit of policy objectives? | Do you feel that the leadership is coercive? Do leaders use power within the institution? | Is there a focus on goals of sub-units rather than the institution itself? Do these usually conflict with the wider goals of the organisation, and hence are unstable and contested? |

| Subjective | Are different meanings placed on organisational structure based on the perception of individuals (e.g., are senior leaders perceived by the Head as participative, but teachers feel they transmit knowledge one way)? Is there more interest in processes and relationships, than structure? | Do those in leadership have their own separate values, beliefs and goals? Do situations arise that require an appropriate response from those best situated to address it (i.e., it doesn’t feel that there is clear leadership)? Do positional and personal power combined tend to command the respect of colleagues? | Do you feel that individual staff are at the heart of the organisation and are not simply regarded as a cog within the institution? Do personal aims of individuals take precedence? Do organisational goals tend to reflect the personal aims of influential people? |

| Ambiguity | Is the organisation characterised by fragmentation and ‘loose coupling’ – i.e., sub-units operating autonomously? Are rules and regulations unclear / disregarded? Is participation in decision making fluid? | Do leaders seem to have little or no control? | Are objectives and processes unclear and not understood? |

| Cultural | Is there a loose link between culture and structure? Do staff work interdependently with each other? Are values and beliefs expressed in the pattern of roles which underpin attitudes and behaviours? Are shared norms and meanings developed: the ‘way we do things around here’? Are beliefs and norms expressed through rituals and ceremonies? | Do heroes and heroines exist who embody the values and beliefs of the organisation? | Is the culture expressed through goals? Are goals and values consistent with each other? Do the vision, mission and the goals align? Is there consensus amongst staff on these things? |

Figure 2: Reflective questions related to each model (modified from Bush, 2020).

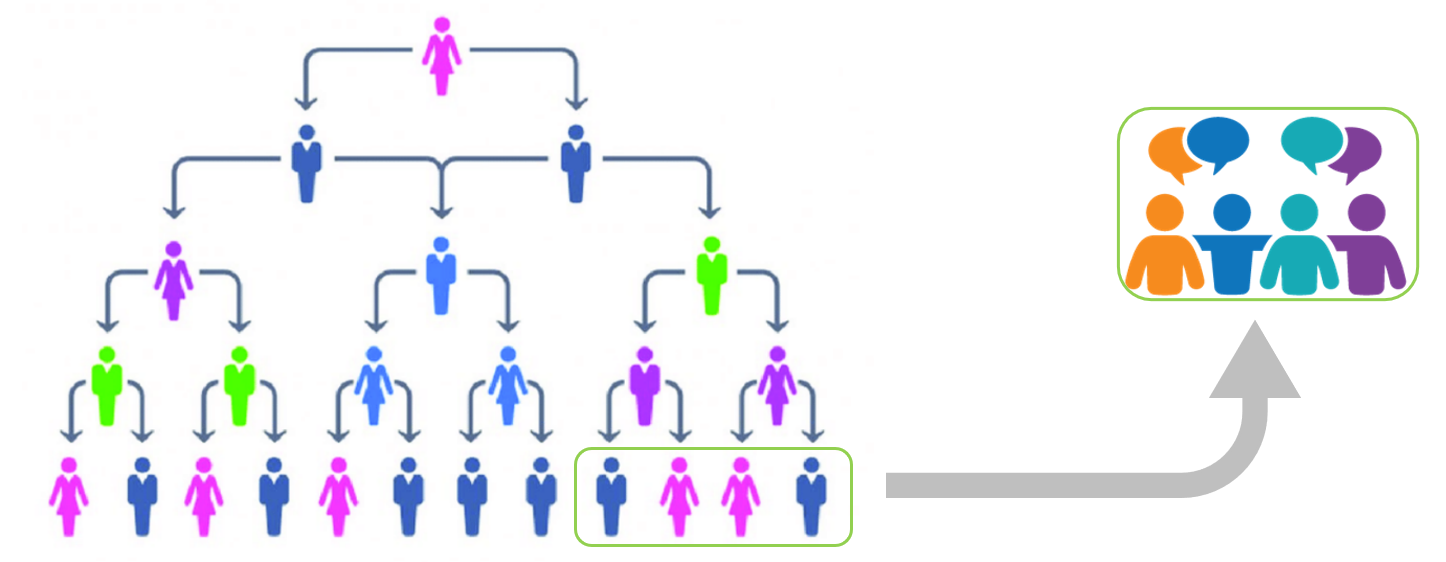

Depending on how you answered the reflective questions above, you may feel that your institutional structure exemplifies more than one model. For example, you may feel that your institution has a hierarchical structure; however, there are tasks and teams that work together in a collegial way.

Figure 3: Formal and Collegial models combined.

Reflection (click to expand)

- How is your leadership role / position influenced by the model your institution seems to have adopted?

As stated in the first reflection post of this series, middle leaders are often opportunistically positioned, or ‘sandwiched’, to be able to listen up, down, across or through the organisational model, in order to effectively implement, and this position could also allow middle leaders to influence and contribute to the wider goals and vision. How a middle leader capitalises on this opportunity could prove beneficial to the setting of more phase and subject-specific goals so that they positively impact change.

Reflection (click to expand)

- Despite your institution adopting a particular model, do you operate with a different model within your own department / team / section?

- Would you like your institution to adopt or move toward a different educational model? If so, which one and why?

*At the time of writing this blog post, Tony Bush is a Professor of Educational Leadership at Nottingham, with responsibilities in the UK and Malaysia. He is President and a Council member of the British Educational Leadership Society (BELMAS) and has been the editor of the SSCI-listed international journal, Educational Management, Administration and Leadership (EMAL) since 2002. His previous experience includes professorial appointments at the universities of Leicester, Reading, Lincoln and Warwick. He was presented with the BELMAS Distinguished Service Award in 2008 and appointed as a Fellow of the Commonwealth Council for Educational Administration and Management (CCEAM) in the same year. He has been a consultant, external examiner, invited keynote speaker and research director in 23 countries, and has also authored a number of his own books focusing on educational leadership.

References

- Bush, T. (2020) Theories of Educational Leadership and Management, London: Sage.