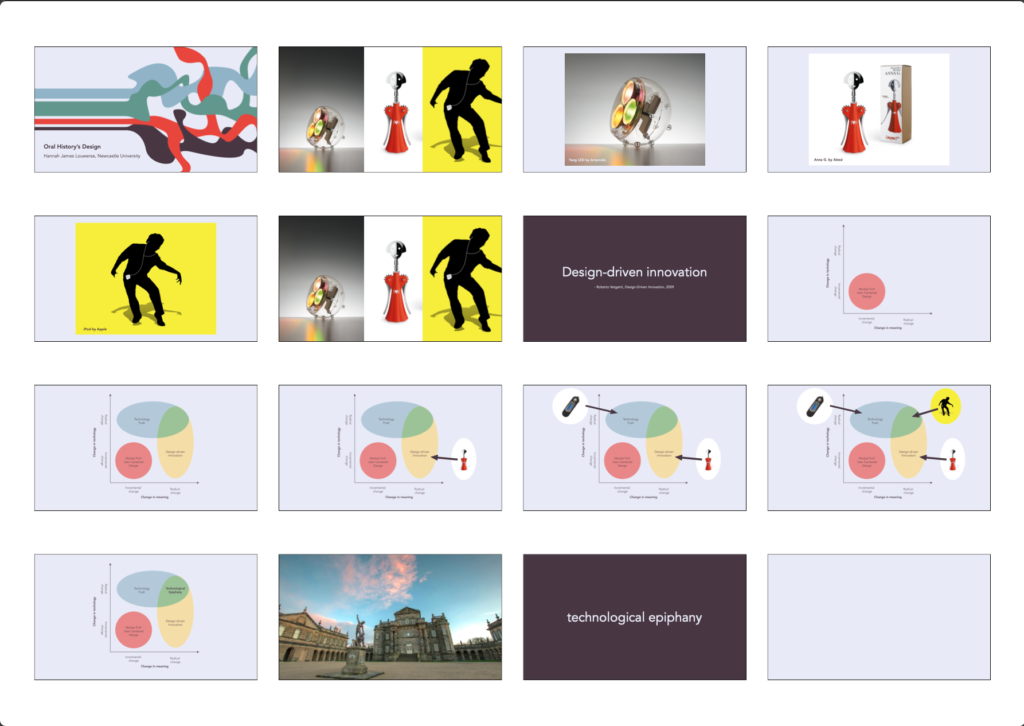

In Back to the Future Part Two, Marty McFly travels to 2015. There are flying cars, holograms, hoverboards, and many many fax machines, but no sign of the internet or smart phones. It is easy for twenty-first century viewers of the film to roll their eyes at this past portrayal of the future, because we are blessed with hindsight. These technologies have so seamlessly integrated into our lives, we cannot imagine a world without the internet or smart phones. People who have been able to perfectly predict future technologies are in a significant minority. The majority of portrayals of the future either have been or will be proven incorrect. This principle can be transferred onto the real world, where people spend their time developing technologies in the hope that it will become the future only for it to miserably fail. Artistic interpretations of the future and experimental future technologies are kindred spirits fuelled by great hope and excitement. In the early 1990s one of the first oral history technologies was born in Alaska at the University of Alaska Fairbanks — Project Jukebox. According to a paper on this digital oral history archive, “a fantastic jump into space age technology awaits the user when he or she sits down before the Jukebox workstation.” (Lake, p. 30) This “space age” technology involved a lot of CD-roms and received support from Apple Computer Inc. (their words not mine) through their Apple Library of Tomorrow scheme. In the papers written on Project Jukebox there is this wonderful sense of hope that technology will solve the problem with reusing oral histories, but like Back to the Future Part Two hindsight makes us shake our heads at talk of CDs. The discussion around copyright is especially alien to 2021 readers as it focuses solely on the copyright of the photographs in the archive, with little to nothing on the copyright of the recordings and no mention of the interviewees’ privacy. (Smith, p. 19) In the first chapter of the book Oral History and the Digital Humanities, Willem Schneider, who was one of the original creators of Project Jukebox acknowledges their hopeful naivety: “we stumbled onto digital technology for oral history under the false assumption that it would save us money and personnel in the long run.” (p. 19) This does not mean that Project Jukebox was a failure, on the contrary, it plays an essential role at the start of the journey of oral history technology. The naive exploration of future technologies is the first stage of all journeys that aim to find a technology that becomes as everyday as the smart phone.

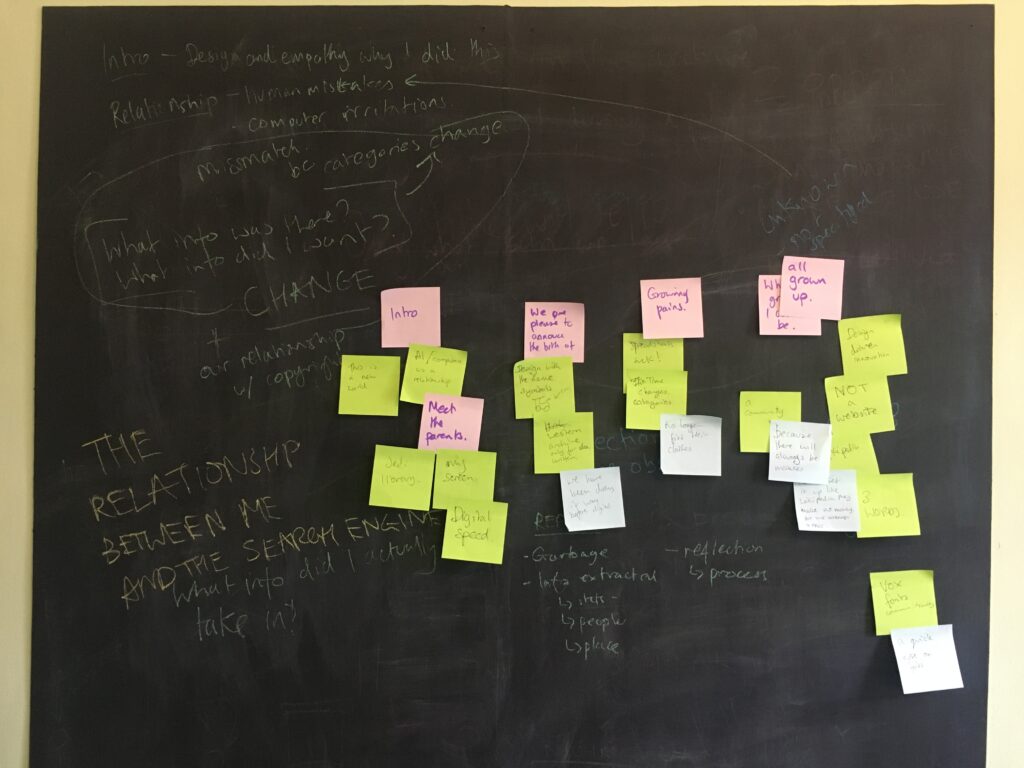

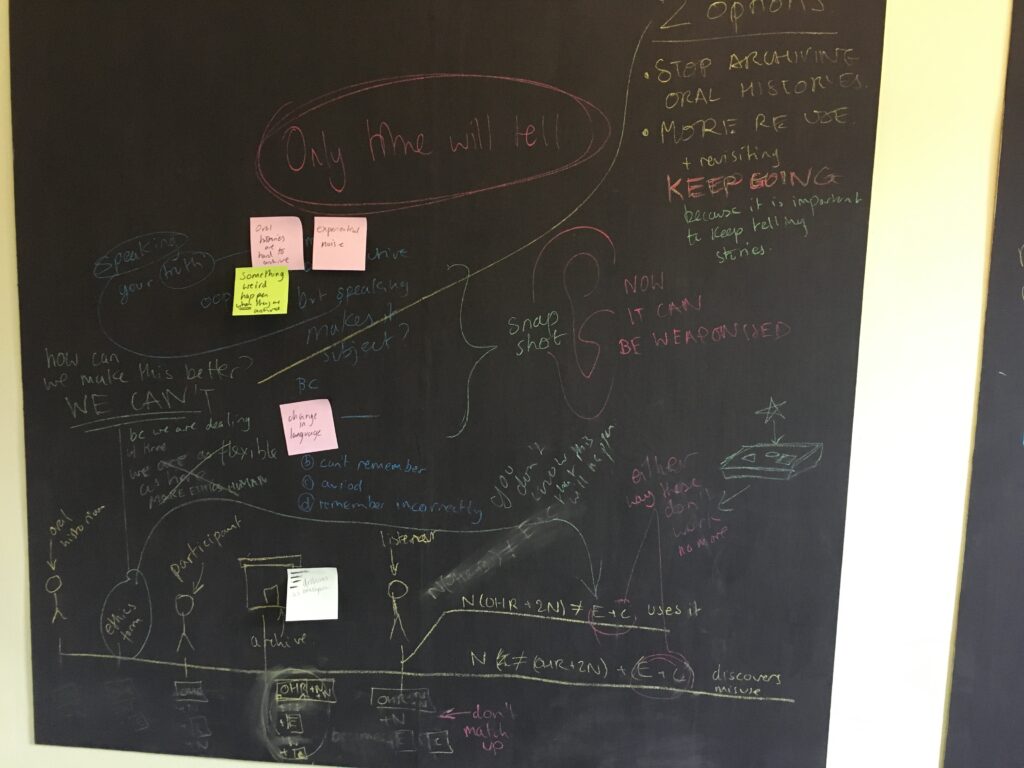

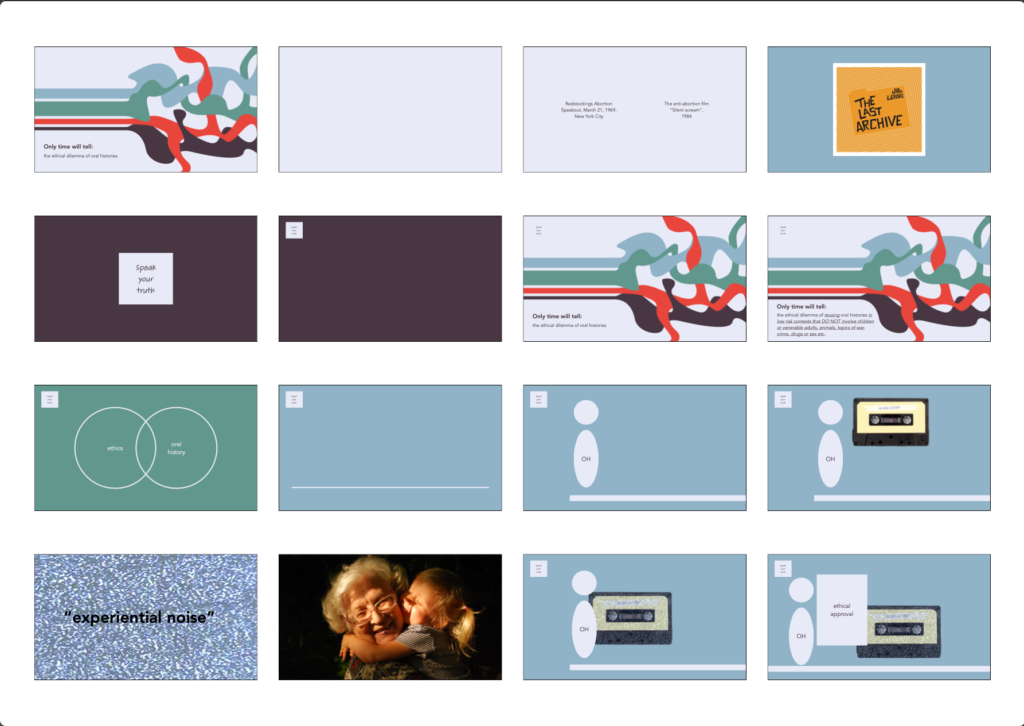

However, the journey from naive exploration of future technologies to seamlessly integrated technologies is a bumpy ride. It is really hard to establish a technology in society. It takes a lot of work and time, and above all — money. In the following essay I am going to look at the journey of digital oral history technologies. I would not be writing this if there already was an established digital oral history technology but, we are also no longer in the naive exploration stage that Project Jukebox started. We are somewhere in the middle, which in my opinion is the hardest place to be: no longer in the fun, playful, and hopeful beginning stages, but still quite a way off a solution. I therefore am not going to talk about which digital oral history technology is the most user-friendly. I believe it would be very unproductive to pit these technologies against each other, instead I want to discuss what I believe contributes to the struggle of establishing a solid oral history technology.

I must confess that the research I had to do for this essay was not the easiest. Not only do many of the oral history technologies no longer exist but there is minimal literature on why they stopped existing. I have a folder filled with papers and articles all on the topic of digital solutions in oral history archiving and reuse. There are many hyperlinks in these documents, some even have QR codes, sadly the majority of them are dead links. I can probably count the amount of links that do work on my fingers, which is not great when you are doing research. From my limited research on these technologies I have however been able to extract a handful of factors that play contribute to the bumpy journey of developing oral history technologies, including the usual suspect — money. But first we need to understand what happens to our storage and preservation systems when we introduce digital technologies.

Tech = Risk = Maintenance = Money

In my house there are several types of analogue storage units: bookshelves, cupboards, drawers etc. If I put a book on a shelf it stays there unless I move it or some uncivilised person decides to remove it without my permission. It is possible I might forget which shelf I put it on and have to spend some time searching for it, desperately trying to remember if I had lend it to somebody. In this scenario in order to preserve, store, and access the book I need nothing more than a shelf to keep it safe, and my brain to remember where it is. This is a pretty stable situation as the shelf does not move and my brain currently functioning fine (touch wood). Now I have found my book I want to put some background tunes on while I read. I get my electronic device (laptop or smart phone); press away the notification that I need to do an operating systems update; realise it has no battery so have to plug it in the mains, after locating my charge; and then finally open my Apple Music application (formally iTunes) and play the song. I might even connect my device to a bluetooth speaker so that the sound is better quality. Here there are a couple more steps and players involved in the storing, preserving and accessing of my song than in comparison with my book on the shelf, but as long as I have the hardware, software, power supply I have access.

However, it is the twenty-first century so nothing actually happens unless you post it on social media. I capture this moment of me reading my book and listening to my music by again using hardware, software, and power supply, but to upload the image onto the storage space of social media several more actors come into play. Firstly, I need WiFi, which is supported by a very complicated infrastructure of towers and wires. Secondly, I need the appropriate social media application, which is supported by a separate infrastructure of towers, wires, and servers. Both these infrastructures rely on a huge power supply to function. If there is any disruption in the internet supply or at the social media servers I cannot store or access my images on my social media profile and can therefore not prove that I read books.

With this narration I wanted to illustrate what happens when we introduce digital technologies to our storage and access systems. I find that there is a direct correlation between the amount of technology needed to store, preserve and access stuff, and the potential risks associated with that same system. In order to avoid these potential risks more maintenance is required, which in turn means that more money is needed to keep everything running smoothly. Doug Boyd, who is the Director of the Louie B. Nunn Centre for Oral History at the University of Kentucky, has experienced how the lack of acknowledgment of the rise in risk, maintenance, and money due to an increase digital technology can be the downfall of an oral history technology. Boyd worked on the Civil Rights Movement in Kentucky Oral History Project Digital Media Database, which in his words was a “gorgeous” website that had “logical” information architecture. However, Boyd also admits that the project was intensely focused on the userbility of the site and actually was more akin to a “complex, elaborate, and beautiful digital [exhibit]” than a digital oral history archive. (2014, p. 89) This user-centric design of the Civil Rights Movement in Kentucky Oral History Project Digital Media Database, meant that the archiving perspective fell by the wayside. There was minimal consideration for the maintenance required to keep all this digital technology running smoothly, and the money needed to sustain this maintenance. Boyd admits that it eventually led to the website being “digitally abandoned, opened up to online hackers and eventually taken down.” (2014, p. 90) The Civil Rights Movement in Kentucky Oral History Project Digital Media Database is an example of the naive experimentation that happens at the beginning of the technological journey. We learn from these experiences and move on, which is exactly what Boyd went on to do.

Growing Pains

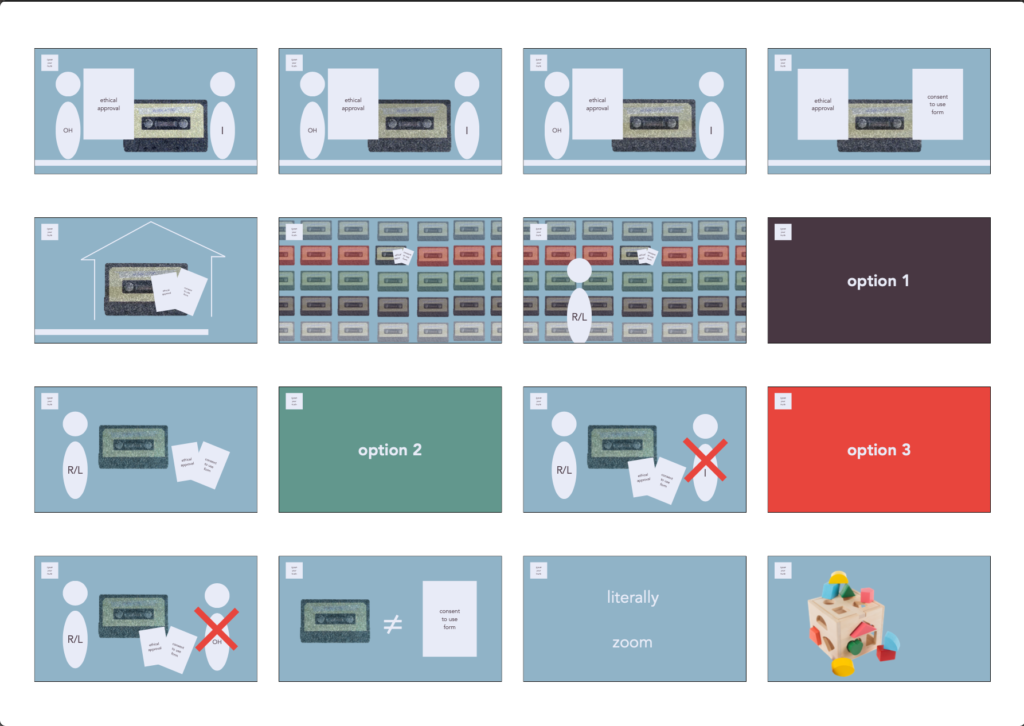

The Oral History Metadata Synchronizer (OHMS) was developed by Boyd after his work on the Civil Rights Movement in Kentucky Oral History Project Digital Media Database. It still exists, which is quite an achievement. Unlike the Civil Rights Movement in Kentucky Oral History Project Digital Media Database OHMS is not a repository but a software that individuals can use to make their repository better. There are two parts to OHMS, the Synchronizer, where the user creates the metadata for the oral history recording and, the Viewer, which makes it easy for others to access and search the oral history recording. (2013, p. 97) When it comes to the amount of digital technology involved in OHMS compared to the Civil Rights Movement in Kentucky Oral History Project Digital Media Database, I cannot say for sure whether it is more or less because I simply do not know enough about their set up. Either way, both are web based, so it is likely to be a considerable amount and definitely more than my bookshelf. Boyd is therefore still battling with the high amount of maintenance, luckily though he is now more aware of it. In a 2013 article he reflected on OHMS’ original shortcomings: its heavy reliance on transcripts and the struggle to expand it beyond the Kentucky Digital Library.

It is well known that text is a lot more searchable than audio files. This is one of the founding ideas of OHMS as it connects up the audio/video file with a transcript. However, not all oral histories have transcripts because they are expensive to make: only big institutions with huge amounts of funding could afford transcribing all the oral history recordings. (2013, p. 99) This is a good example of how technology dictates the amount of money and work needed. OHMS’ technology needed transcripts to work, but this requires a lot of work and money, making the system a very exclusive product. Boyd, however, went back to the drawing board and, inspired by Michael Frisch’s ideas around indexing, altered OHMS to be able to also run off indexes. Indexing involves a lot less work which means it is cheaper. (2013, p.100) The technology also does not suffer because indexing is text based. The quick text searches which was the foundation of the original OHMS design can still be run.

When it comes to the issue of moving OHMS beyond the Kentucky Digital Library Boyd’s has a little less to write in his 2013 paper. (2013, p. 105) I find the tone in this section similar to the Project Jukebox papers; filled with hopes and goals for the future. There is a hint of awareness that the road is rough ahead, OHMS is open source which Boyd admits “does not always mean free or simple”. However, the following to me is the stand out hope:

The hope is that smaller historical societies or similar organizations with very limited budgets and almost no IT support can take full advantage of the OHMS system for presenting oral history collections online. (2013, p. 105)

This to me feels like a very distant future. These technological solutions, Project Jukebox, the Civil Rights Movement in Kentucky Oral History Project Digital Media Database, OHMS, have all been developed and used within universities which have relatively high (although not enough) access to funding opportunities. But I also do not believe that money is the only barrier to achieving Boyd’s dream. I have suspicion that “limited IT support” is a barrier that is higher than we think.

DIY Digital

Computers are magical. They can do really amazing things. However just like a hammer or a paint brush this magic can only be unlocked by a skilled user. Computers are after all no more than very complicated tools. Their complicated nature has sadly resulted in only a select group of people (mostly men) fully understanding the ins and outs of these tools. This discrepancy between those who do understand computers and those who do not is referred to as the “digital divide”, a termed coined in United States during 1990s. The digital divide refers to the differing levels of access to hardware, software, and the internet. Professor of Communication Science at the University of Twente, Jan A. G. M. Van Dijk explains in his 2017 paper, Digital Divide: Impact of Access, how in the early 2000s the main focus of the research into the digital divide was on digital infrastructure and access to physical devices and the internet (p. 1). In recent years the idea of access has been broadened to include the skills needed to access and retrive information and increasingly, the skills needed to communicate through various mediums, and create content. The reason for this expansion is because digital inequalities did not disappear in places where there was unilateral physical access to digital technologies. Van Dijk believes that digital inequality only truly starts after digital media had become defused into our everyday lives (p. 2). He splits the digital divide into three types of access: physical, skills, and usage. I will be focusing on the latter two and the divide that occurs after physical access has been achieve.

The access granted by skills can be view from two directions: the creator and the user. I would like to start by looking at how skills can facilitate access in the former and then look at skills and usage from the perspective of the user. Willem Schneider writes that there are three main roles in oral history preservation: the oral historian, the collection manager, and the information technology specialist. If we consider the things I talked about in the previous section, the preservation of the oral history relies increasingly heavily on the skills of the information technology specialist, especially when things are moved online. They are the ones who have to handle the risks and maintenance of the digital technology involved in the project. Their computer and digital skills directly influences and limits the preservation and access of the oral history recording.

In the case of Stories Matter the person taking on this role was Jacques Langlois. Stories Matter started as a in-house database software created at the Centre of Oral History and Digital Storytelling at Concordia University in Montreal. In the abstract of an article on the development of the software, Stories Matter is described as a programme that “encourages a shift away from transcription, enabling oral historians to continue to interact with their interviews in an efficient manner without compromising the greater life history context of their interviewees”. (Jessee, Zembrzycki, High, p. 1) Jacques Langlois was the software engineer from Kamicode software, who mostly had experience in developing video games and no experience with oral history. (Jessee, Zembrzycki, High, p. 5) As a software engineer Langlois has a higher level of digital skills in comparison to the rest of the team working on the software. There was a clear digital divide between the rest of the team and Langlois. This only expanded when Langlois decided to use the the runtime platform Adobe Air, which the rest of the development team had little to no knowledge of and therefore were unable to support Langlois in his development. (Jessee, Zembrzycki, High, p. 6) How the individual team members approached the development of the software was also a result of their in-team digital divide. The oral historians viewed the software as something made for oral historians by oral historians and were primarily focused on userbility, which as I previously discussed was something Boyd has noted as the downfall of the Civil Rights Movement in Kentucky Oral History Project Digital Media Database. Meanwhile Langlois simply wanted to make sure that the software did not crash and ran smoothly. The digital divide in the team and the pressures on Langlois are perfectly illustrated in the article on the programme through a frustrating bug finding saga. (Jessee, Zembrzycki, High, p. 9)

As far as I can tell Stories Matter no longer exists. The majority of the links in the article on the software are dead and, although Stories Matter does have a page on the Kamicode software website, I am unable to download it. As I mentioned in the first section of this paper building an application software and keeping that sustainable and updated takes up an insane amount of money, labour, and time. You cannot just make an application and hope that it lasts forever because it will not. Technology is constantly evolving; new devices are developed and the operating systems are constantly updated by their own developers.

When it comes to the user side of oral history technologies I would like to start by highlighting that the majority of the time oral historians do not use bespoke oral history software. In a paper on the now non-existent InterClipper software Douglas Lambert and Michael Frisch identify a couple of “caveats” when it comes to their use of technology. When reflecting on the 1990s cyber punk roots of the digital age they admit that a do-it-yourself mentality of “rummaging around in our virtual toolbox” instead of “waiting for the “perfect software” or a single methodology to resolve the complex challenges of oral history practice in the digital age” is often a cheaper, quicker, and more effective way of analysing oral histories (p. 142). This does not mean that oral historians should adopt an exclusively DIY approach and give up making a more appropriate oral history software. However, I do believe that maybe reflecting a bit more on the tools we already use and searching within the parameters of our own digital skills, we might save some time and money. Most importantly I believe that this attitude can help us stay grounded and stops us from getting swept away in the magic of digital technology. In addition I believe that this principle can be extend to encompass not only our digital skills but also our personal research skills.

I did it my way

In the document on Stories Matter the writer discuss InterClipper and their experiences of using it. InterClipper was initially a software developed for market research and was enthusiastically adopted by Michael Frisch in 1998. The appealing thing about the software was “the seamless linkage between the digital audio/video files and a fairly robust multifield database for annotating and marking audio/video passages.” (Lambert and Frisch, p.137) However, according to the Stories Matter team, the students who tested out InterClipper found a handful of problems with the software. They did not like that the oral history recordings had already been clipped. The students found that they clipped recordings were difficult to navigate and they lost the wider context of the life history. Furthermore, they disliked the indexing which they found “too scientific.” (Jessee, Zembrzycki, High, p. 3).

To clip or not to clip? To transcribe or to index? Text verses audio verses video. I have heard all sides of the all of these arguments. When it comes to digital skills the DIY attitude is about whether the individual can use Microsoft Word or Adobe Audition, however with usage it is about how people research and their preferences when it comes to consuming knowledge, which can be a very personal affair. To start with people might have a physical or learning disability which restricts how they can research. People also have different learning styles. (Marcy) I, for example am a visual and audio learner, which means that I struggle with reading, and if there is the option consume the information through a documentary or podcast I will take it. People also have different motivations to access an oral history. An oral history is a multilayered artefact, a cornucopia of stories, which holds information that can be useful to a wide range of people from different fields of work and research. However, many of these softwares are created at universities: Stories Matter at Concordia University, Project Jukebox at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, and OHMS at the University of Kentucky. These softwares will undoubtedly be influence by the environments in which they were made. In the case of Stories Matter the software was explicitly made for oral historians by oral historians, which is a pretty exclusive attitude. This also reenforces digital inequalities as Van Dijk says that the biggest digital divide in terms of usage is between those who have a higher education and those who do not. (p. 8)

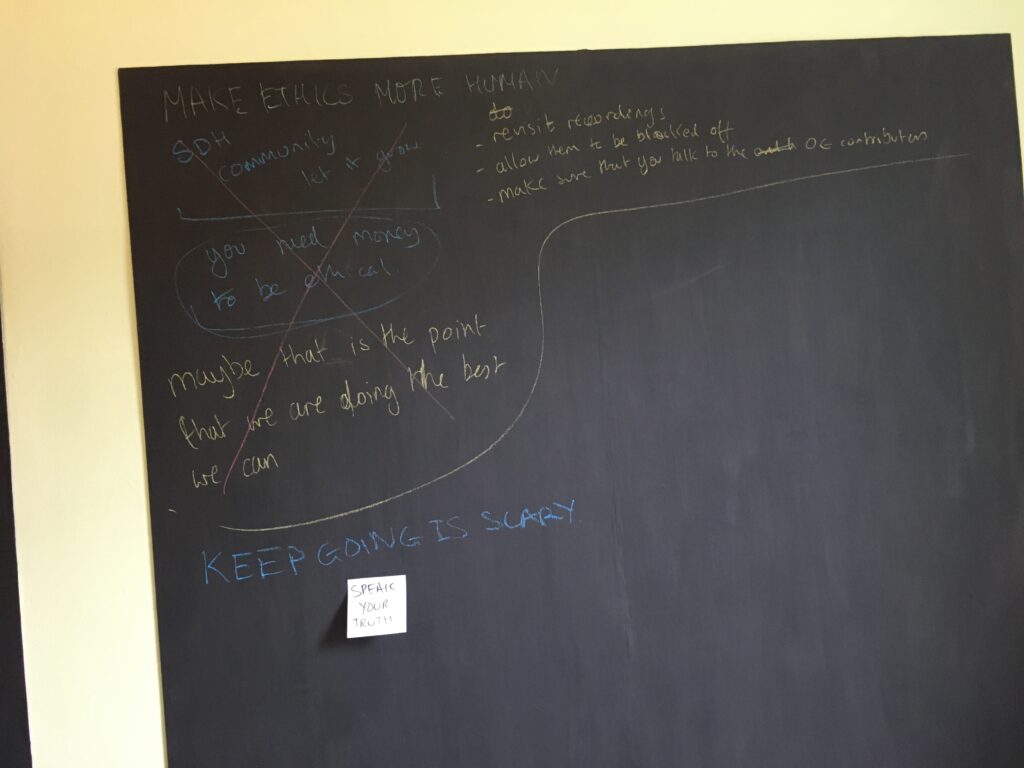

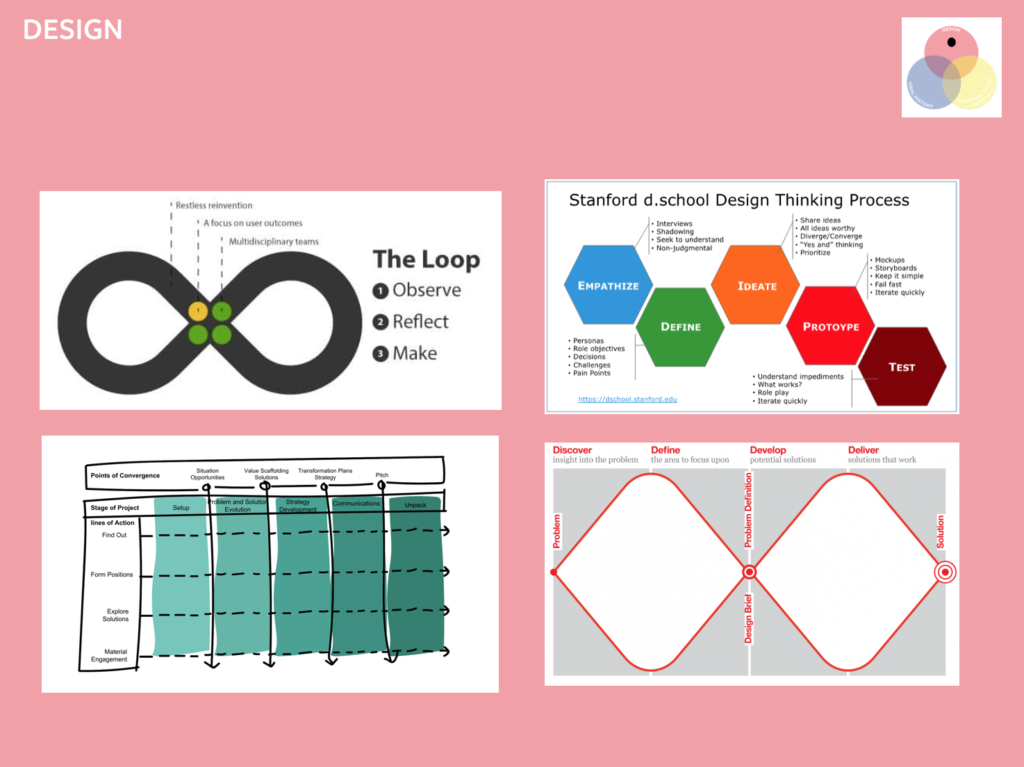

It is not particularly radical to conclude that everyone is a unique being that does things in their own way. However, it is very important to remember this when you are designing something, which is exactly what the oral historians involved in these technologies are doing. In his zine, Ruined by Design: How Designers Destroyed the World and What We Can Do to Fix It, the designer Mike Monteiro outlines a code of ethics for designers. One of the things included in his code is “a designer does not believe in edge cases”. (p. 37) There is a history in design to have a target audience for your product, this by default means that you also have a non target audience. According to Monteiro this basically means you are marginalising people: you are actively deciding that your product will not be used by other people. He gives the example of Facebook’s real names projects, which affected trans people and people of indigenous backgrounds whose names were not consider “real”. But he also gives examples beyond Silicone Valley of single parent households “who get caught on the edges of ‘both parents must sign’ permission slips”, or voting ballots in America only being in English, excluding those of immigrants who have a right to vote but struggle with English. (p. 38) Within the setting of the oral history technologies I have talked about, the statement “a designer does not believe in edge cases” means that thought needs to be put into the differences between people’s digital skills and their research preferences. This applies both to the creator and the user of the oral history technology. Selecting who you are designing for in statements like “for oral historians by oral historians” is not caring for the edge cases, which in a field like oral history where one of the founding principles was giving a voice to the voiceless is shameful.

Forward to the Past

Imagine if they remade Back to the Future but kept it in the same time settings as before. Marty McFly would then be able to travel to the real 2015 and be thoroughly disappointed that everything kind of look the same accept no one would look him in the eye because they were all looking down at their phones. Imagine the audience’s disappointment when they presented, not with the magical flying car technology of the original movie, but the painful reality of a 2015 where we did not have the technology for hoverboards. Below you can see the interfaces of Project Jukebox in 1990 on the left (Smith, p. 17) and a screenshot of their website in 2021 on the right.

Back to the Future Part Two’s 2015 is the embodiment of the hopeful dream that is so heavily associated with technology. The same magic that can be felt in the papers on the original Project Jukebox which created the interface on the left. The real 2015 was more like the current interface, similar to what came before only now you can view it on a different device. Many people would take one look at the Project Jukebox’s interfaces and roll their eyes. They might ask, why has so little changed in the last 30 years? Hopefully, I have been able to slightly answer that question. Over the last 30 years oral historians have been wrestling with digital technology, searching for the best solution, only to end up penniless, tired and confused with only a few dead links to prove that something might have existed at some time. This might be a slight exaggeration. We have come far in the journey of oral history technology. However, I do wonder if we would not benefit more from looking back on our past, evaluating our failures, acknowledging the maintenance required, and using our old methods and DIY technologies as inspiration for our next creation. Maybe this will be a better way to continue instead of chasing the Back to the Future – esque dream of the perfect oral history technology.

Bibliography

Boyd, D. (2013) “OHMS: Enhancing Access to Oral History for Free” in The Oral History Review. 40(1) pp. 95-106

Boyd, D. (2014) “’I Just Want to Click on It to Listen’: Oral History Archives, Orality, and Usability” in Oral History and Digital Humanities ed. D. Boyd and M. Larson. pp. 77-96. Palgrave Macmillan: New York.

Jessee, E., Zembrzycki, S. and High, S. (2011) “Stories Matter: Conceptual challenges in the development of oral history database building software” In Forum: Qualitative Social Research. 12(1)

Lake, G. L. (1991) “Project Jukebox: An Innovative Way to Access and Preserve Oral History Records” in Provenance, Journal of the Society of Georgia Archivists. 9(1) pp. 24 – 41

Lambert, D. and Frisch, M. (2013) “Digital Curation through Information Cartography: A Commentary on Oral History in the Digital Age from a Content Management Point of View “ in The Oral History Review. 40(1) pp. 135-153

Marcy, V. (2001) “Adult learning styles: How the VARK learning style inventory can be used to improve student learning” in Perspectives on Physician Assistant Education. 12(2) pp.117-120

Monteiro, M. (2019) Ruined by Design: How Designers Destroyed the World, and What We Can Do to Fix It. [EBOOK] Mule Design: San Francisco

Schneider, W. (2014) “Oral history in the age of digital possibilities” in Oral History and Digital Humanities ed. D. Boyd and M. Larson. pp. 19 – 33. Palgrave Macmillan: New York

Smith, S. (Oct 1991) “Project Jukebox: ‘We Are Digitizing Our Oral History Collection… and We’re Including a Database.’” at The Church Conference: Finding Our Way in the Communication Age. pp. 16 – 24. Anchorage, AK

Van Dijk, J.A. (2017) “Digital divide: Impact of access” in The international encyclopedia of media effects ed. P. Rössler. pp.1-11. John Wiley & Sons: