Tag Archives: Data

OHD_BLG_0034 21st Century Ghost

Have you ever heard of the twenty-first century ghost? You have definitely seen it and heard it. It hides in many places, but its favourite spot is in the pocket of your trousers, next to you on the table or in the palm of your hand. The ghost of the twenty-first century lives in the interactive rectangle that is your smart phone. This ‘digital urn’, as described by Kirsty Logan in the podcast series A History of Ghosts, is filled with your voice, your face, your ideas, your questions, your life. Every day we work on growing our own twenty-first century ghost by feeding it incredibly personal information and preserving it in our digital urn. But our twenty-first century ghosts’ range is not limited to our smart phones, they spread across the world, roaming around social media servers and traveling in the inboxes of other people’s digital devices. The average person has no control over what can be found in their digital urns, what past lives the ghost can expose and havoc it can cause.

Some people have a different type of ghost, one that is a little more timid and introverted. If you have ever taken part in an oral history project you probably have such a ghost; a recording of your life’s story told by you living in an archive staying put until someone calls on it. In order to put an oral history interview into an archive and create an archival ghost, one has to fill in what seems endless ethical approvals, consent forms and permission slips. These documents are there to highlight the potential “dangers” of having something in an archive: how you privacy might be violated or how someone could misuse your testament and twist your words. Social media sites do a similar thing, only they condense the stacks of paper into one tick box. Clearly the archiving process is more transparent in comparison to the methods use by those in the Silicone Valley, which at best are questionable and at worst violate basic human rights, however transparency does have its drawbacks.

The reaction people have to this transparency is similar to that when you ask some people to travel by air. People are terrified of flying because they are fully aware of how wrong it can go, but statistically it is a lot safer than walking to the corner shop. Just like the designing an aeroplane, archiving an oral history has to follow certain rules from the start, because those involved, aerospace engineers and oral historians, are fully aware of the chaos and pain it could cause if the systems fail. Having these restrictions is seen as more ethical, but it also inadvertently puts disproportionate emphasis on the dangers of archiving (and flying). In opposition, walking, like the ticking of the terms and conditions box, is easier and it delivers blissful ignorance to the high probability of being hit by a car or having one’s data stolen. Unlike the oral historians and archivists, the developers of the uncomplicated tick box view their users as nothing more than data sets and potential profit. Some could say that this has led them to be dismissive of a human’s right to privacy and be vague when it comes to revealing the true cost of using one of their platforms. However it seems that by not drawing attention to terms and conditions, people have become very happy to hand over their personal information.

The existence of these two ghosts, the restricted and timid archival ghost, and the free and uncontrollable twenty-first century ghost, makes the people’s relationship to their privacy seem incredibly distorted and ill-informed. It seems odd to trap the archival ghost with paperwork in order to protect their corresponding human, when that exact human is completely content with sharing every single part of their lives with strangers on the internet. However, it is this sharing that is key to success of social media. By giving up their privacy the users of social media are granted access to a huge network of listeners and viewers. After all a story is not a story if there is no one to listen to it. By the same logic if the oral history is never reused, the archival ghost is never called upon and the story is never listened to, its very existence becomes void. So this raises the question: should we even bother archiving oral histories in the first place if the paperwork blocks it off from listeners? For the sake of my research we’ll say yes, in which case let’s follow it up with the question: should we be more like Silicone Valley and be a little less pedantic when it comes ethics?

For now I am going to go with yes and no. The current process around ethical archiving does need updating but because I also fundamentally believe that Silicone Valley is wrong and I think people are starting to catch on. People are becoming increasingly aware of what their twenty-first century ghost might expose. For example, a growing number of people are being ‘cancelled’ because the public have dug through their digital urn and found a tweet they sent when they were twelve and used a term that is now considered very derogatory. There is also a generation of people, who are unhappy with their parents relentless ‘sharenting’. Sharenting is the practice of posting everything your child does online, which results in the child having a data presence before they can even speak and therefore give consent to its existence. This faint atmosphere of mindfulness around posting, uploading and sending is descending over the digital world. People are reflecting on the ghosts they have created and are now trying to do damage control.

Currently the archival ghost and the twenty-first century ghost are two extremes on the scale of privacy and its corresponding ethics. However, the increased awareness around the rabidness of the twenty-first century ghost is pushing it along the scale in the direction of the archival ghost. I believe it is now the turn the archival ghost to make a similar move towards the centre. There needs to be more innovation when it comes to the ethics of archiving because at present it is stopping people listening back and that is truly a shame. People bond over sharing stories, they create communities around the most random of things and social media proves this. However social media also showcases perfectly the consequences of condensing very complicated ethics into one tick box for the sake of ease. Changes need to be made on both sides of the scale. By observing the current situation on each side, investigating the pitfalls, challenges and opportunities, and reviewing how different people in the respective fields are attempting to solve these problems, we can start seeking an equilibrium and find a balance between private and public. This managing of our ghosts is a strange and distorted process that is only in its infancy, but hopefully by the end we will be able to free the locked up archival ghost and calm the twenty-first century ghost.

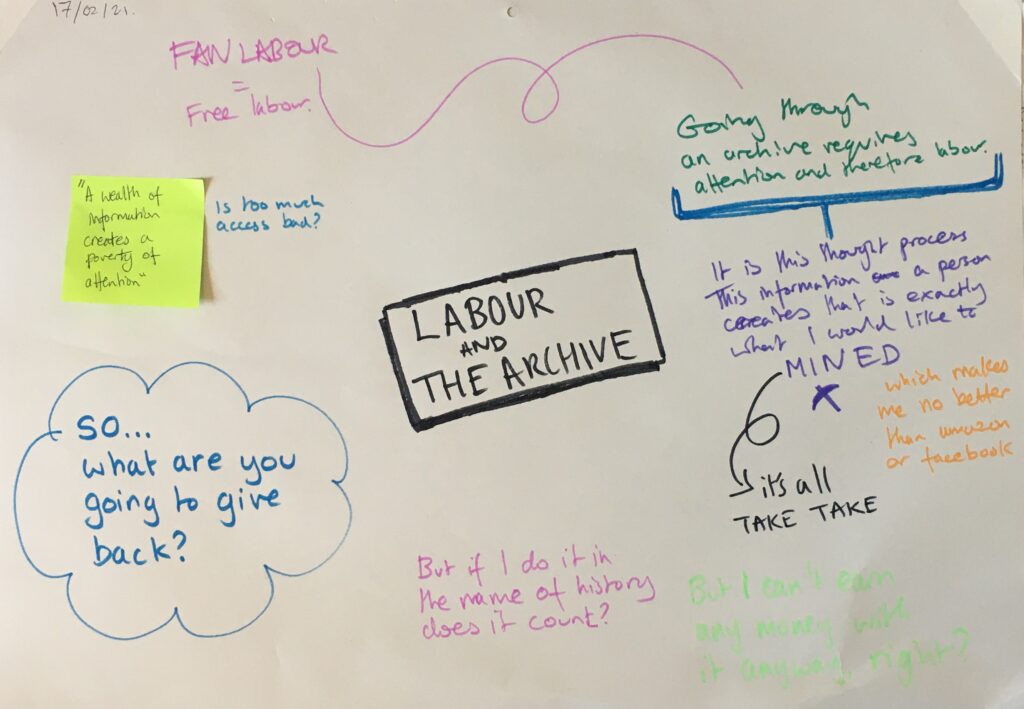

OHD_MDM_0019 Mind map about labour and the archive

OHD_LST_0123 questions

Here is a collection of questions I have asked myself concerning the topic of my PhD both big and small.

How do we handle the racism that exists in the archives? Date: 16/06/2020

What do we do with unused interviews? Date: 19/06/2020

Do we need to reevaluate how we create oral historians in order to ensure more equality within the sector? Date: 16/06/2020

What is the difference between a documentary and an oral history project or article? Are they not both curated equally? Is the only true form of oral history stuck unedited in the archives? Date: 20/07/2020

How can we utilise Gen z and the digital natives in oral history archives? What might the pitfalls be? Date: 21/07/2020

Do I have a problem with the word history in the context of oral history interviews? Date: 21/07/2020

Are there any aural oral history papers? If so where are they and why aren’t there more of them Date: 01/10/2020

How does the archive function in a ‘knowledge/data’ economy? Date: 23/10/2020

Do filters for the public limit or increase accessibility? Date: 23/10/2020

Are we looking for an ‘archive’ or a completely new system? Date: 23/10/2020

What should an archive be like during an pandemic? Date: 08/02/2021

How does “Material History” work in the context of oral history? Date: 08/02/2020

Do we get bogged down in the ethics? Date: 16/02/2021

What is our relationship to the ‘public’? Date: 16/02/2021

What does digitization replace? Date: 10/03/2021

Are result lists the problem when it comes to searching? Date: 12/02/2020

What does it mean if people can’t remember? When people are scared of not being able to remember? Date: 16/03/2021

Where does intertextuality and oral history theory end and academic snobbism begin? Date: 16/03/2021

Is having an oral history recorded like donating your body to science? Date: 16/03/2021

What do the interviewees think about reuse? Date: 16/03/2021

How do we take stuff back to the interviewee? Date: 16/03/2021

How do you build a community? Can you build a community? Or do they only grow naturally? What is the balance between setting up/designing a community and having one naturally occur? Date: 30/04/2021

Can the digital ever be transparent if those who make it are from one exclusive group? Date: 11/05/2021

Do we trust archives? Date: 11/05/2021

Does our idea of original need to change? Date: 11/05/2021

Can you democratise history outside of a democracy? Date: 07/05/2021

OHD_BLG_0087 Design Thinking Sprint report – 03/02/21

I did a mini design sprint today. It was really fun to do something design-y after such a long time. It was about data and data collection. At the beginning the workshop lead showed us different data collection tools, including ‘My Activity’ page on my Google account. On this page I could see what they had been tracking but I also saw how I could turn them off or at least ‘pause’ them. This makes me think that they can unpause them at some point like how your bluetooth automatically switches on all the time.

During this mini design sprint we were challenged to design the app for Newcastle University, which is something I had already done for the university across the road during MDI. The end product my team came up with was a personalised data set report.

The main aim of the personalised data set report was to make the data less passive. We found that the way the data was presented in an example version of the app was flat and not very informative, so we wanted the information to be more personalised. The idea of having the data set report was because I asked the others if they would actually look at this information every day if they had access to it? The answer was no, they won’t look at it every day, but they might if one, it wasn’t constant and two, if it was personalised. So we made the personalised data set report.

This way the information can be condensed and the user can get a better overview of their data over a certain period of time, instead of being bombarded with information constantly. The second thing we did was make the data less passive by getting the user to respond to it. For example, the user could put in targets in response to the data set or they could tweak their recommendations to get the app to push for a different genre of event.

The lead was very happy with our idea.

My big problem with data collection is that one, it’s sneaky, two, it’s too much and three, I don’t have easy access to it. Basically you can boiling these three points down to one – data collection is not user friendly. Firstly, the user is often unaware of it because it is hidden in long ass terms and conditions. Secondly, the shear quantity of data mined off one person makes it impossible for that same person to look through it and digest it. And lastly, the user does not have access to it or at least the access is hidden and complicated. I need to read up on the freedom of information act…

I just realised this is the exact point that guy tried to make to Cambridge Analytica and Facebook in the Great Hack and real life obviously.

BTW did you know that there is an online library which you can log onto and sit in a virtual library? I need to know where to find it.