A brainstorm document about an alternative GLAM space. It was interactive but that made it too big to upload.

Tag Archives: Design

OHD_LST_0128 experiments

In an attempt to create order in the chaos of my mind I thought that it would be helpful to also write all the ideas I have thoughout this process alongside all the questions, insights I have.

The Shelter for Phantom Voices

This idea came to me while I was doing a podcasting workshop (26/04/21 – 27/04/21). Combining the Last Archive podcast and the book Imaginary Museum and then ripping them off, I decided to make the Shelter for Phantom Voices: home of oral history. I thought it would be a good idea to used different oral history projects to illustrate the various challenges and opportunities that can be found in the field of oral history.

I don’t know whether I’ll make it into a podcast or just keep it as a mind palace for myself but either way it is a fun way to think about it.

Pop-Up Archive

I was zooming with Emma because we need our bi-weekly PhD vent. She had been busy with ethics forms which was driving her crazy and I had been thinking about reusing archives (duh). This combination led us to brain storm how you can make an archive pandemic and power-cut proof, while also sticking to GDPR regulations. Our conclusion, a pop-up archive where you can simply hear the oral histories live from the people without any recording. You see if there isn’t a document you do not need to worry about GDPR, power cuts or pandemics because the archive lives within the people. Inspired by oral tradition of Anansi the histories live within the generations through pop up archives. No collection, no storage problems.

PhD student seeking…

Since my roots lie with fine art and I am a strong believer in art as a frontier of exploration, I find it fitting that I should start this project with some type of collaboration with art students. I imagine this would involve me commissioning artists to create pieces that explore the ideas of: sustainability, audience participation, legacy, evolution, story telling, manipulation etc. Should be fun.

Continuing this idea but expanding it to software developers and architects.

The diverse feminist experience

I am currently (21/07/20) watching the drama series Mrs. America, which is about the ERA (equal right amendment) in 1970s America and the women who are both for and against it. The drama demonstrates perfectly how difficult it is for feminist unity because everyone has different life experiences. Women of colour have a different story to white women, young and old differ, lesbians and straights, rich and poor. It is a mess and the exact reason that when my brother asks why can’t women do what #blacklivesmatter protesters do, I reply with it’s just too complicated.

However what this particular situation offers is an extreme situation and extreme situations are very helpful in the case of designing something (Tim Brown, Change by Design). With this in mind I believe that an experiment involving the various opinions of a diverse group on the topic of feminism could provide an exceptional interesting source of footage. Something that could possibly be edited to fit any point of view.

I therefore imagine collecting this in a Photo Booth set up on, lets say, the university grounds and then later inviting people to create their own interpretation of the footage.

I think the aim of the experiment would be to see if you can edit any footage to fit your opinion even if you have collected a wide range of opinions.

Alternatively…

I could make a set up where you can answer a question and leave a question. Like a chain of opinions. Completely random. Could be a website or an installation of some kind.

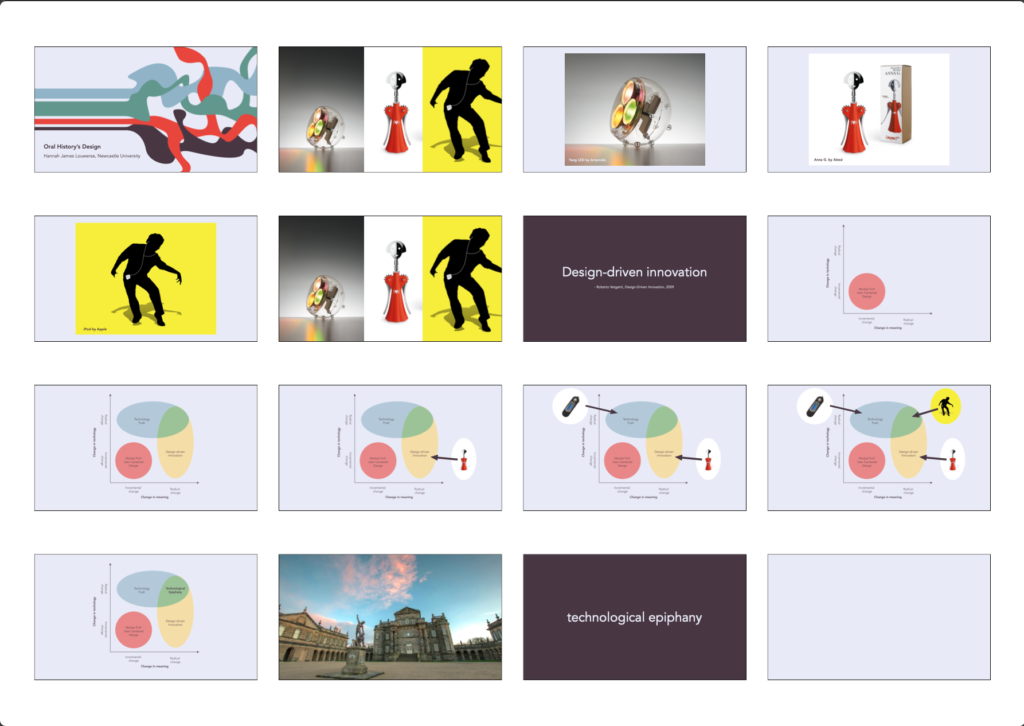

OHD_PRS_0126 Oral History’s Design

This presentation was only 3 minutes. There were some lovely archive nerds in the audience.

Slides

Script

[slide one]

What do this lamp, this corkscrew and the iPod have in common?

Other than the fact that they are all very colourful, they also all radically changed the meaning of their use in comparison to their predecessors.

[slide two]

Lamps are there to illuminate a room and look pretty.

But Yang LED was made to adapt to the mood of resident and is not even meant to be seen.

[slide three]

Corkscrews are there to open my wine

But this corkscrew by Alessi “dances” for you.

[slide four]

Portable music players allowed you to listen to music on the move.

But the iPod allowed you to cheaply buy songs from iTunes and then curate them into your own personal soundtrack.

[slide five]

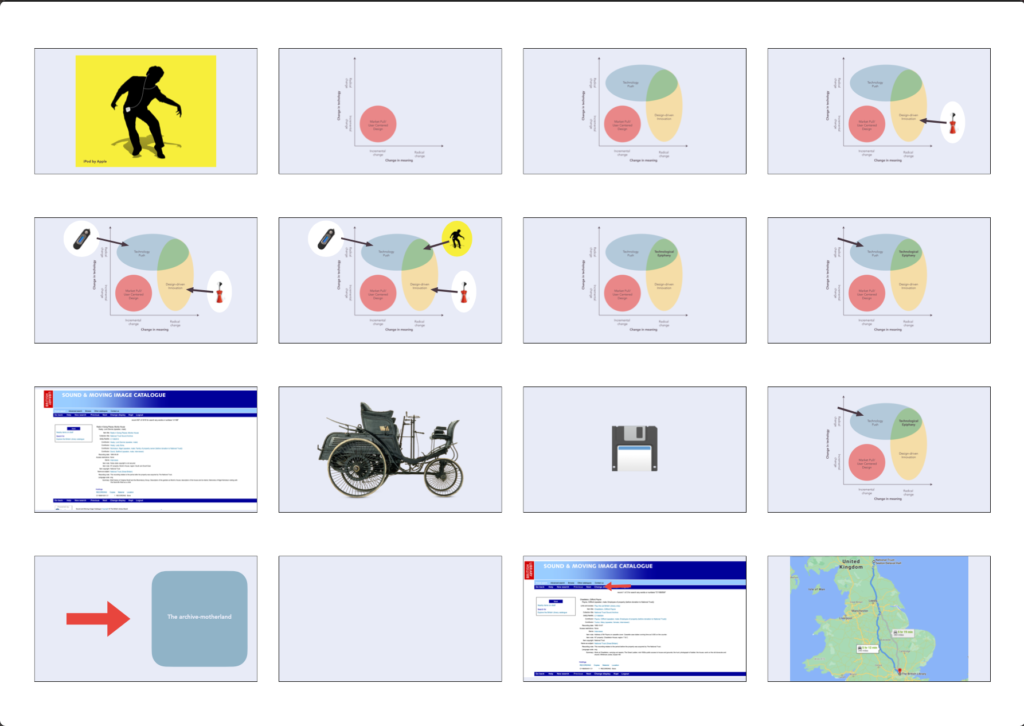

All three of these examples and their respective change in meanings are the result of design-driven innovation a term used by the design scholar Roberto Verganti in a book by the same name.

Design-driven innovation works like this…

[slide six]

Here on this graph we have two axis: change in technology and a change in meaning both have a scale from incremental to radical change. In the corner we have market pull/user-centered design.

[slide seven]

Here we have the bubble design-driven innovation, where see radical change in meaning and the bubble technological push where there is radical change in technology.

In this yellow part where there is a radical change in meaning but not in technology we find designs like alessi’s corkscrew.

In this blue section we find technologies like the first mp3 player, which was a significant technological upgrade from portable cassette and cd players.

Now in this green part we find the iPod.

[slide eight]

This is green part is what Verganti refers to as a technological epiphany.

[slide nine]

My PhD is in collaboration with the National Trust property Seaton Delaval Hall. This property wishes to create an oral history archive and the reason that I started this presentation by talking about the now obsolete iPod is because just like Apple did in 2001 I would also like to achieve a

[slide ten]

technological epiphany.

[slide eleven]

Presently archives are very busy digitising their collections which is great especially during the pandemic.

[slide twelve]

However this push to digitise fall very much in the blue technological push category. Everyone else is online so archives better move there too. The result of this however is websites that look like this.

[slide thirteen]

Not particularly sexy or even that helpful.

[slide fourteen]

What I want to do with my project is actually stop and think about how this technology could actually change the meaning of archiving.

[slide fifteen]

Venganti describes the many ways one can achieve this but it all boils down to doing a lot of talking across disciplines.

[slide sixteen]

How would a graphic designer redesign this page? How does the PhD student feel when they are in an archive? How would an environmentalist make a sustainable archive? How do game designers handle information? Many questions, a lot of information and hopefully a change in what it means to archive.

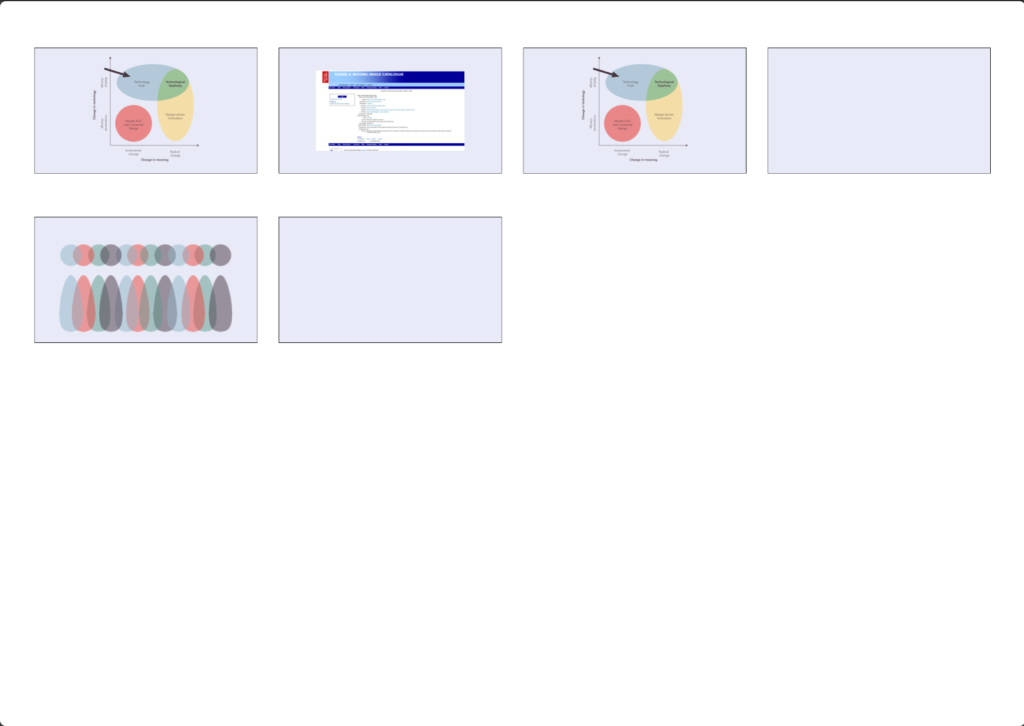

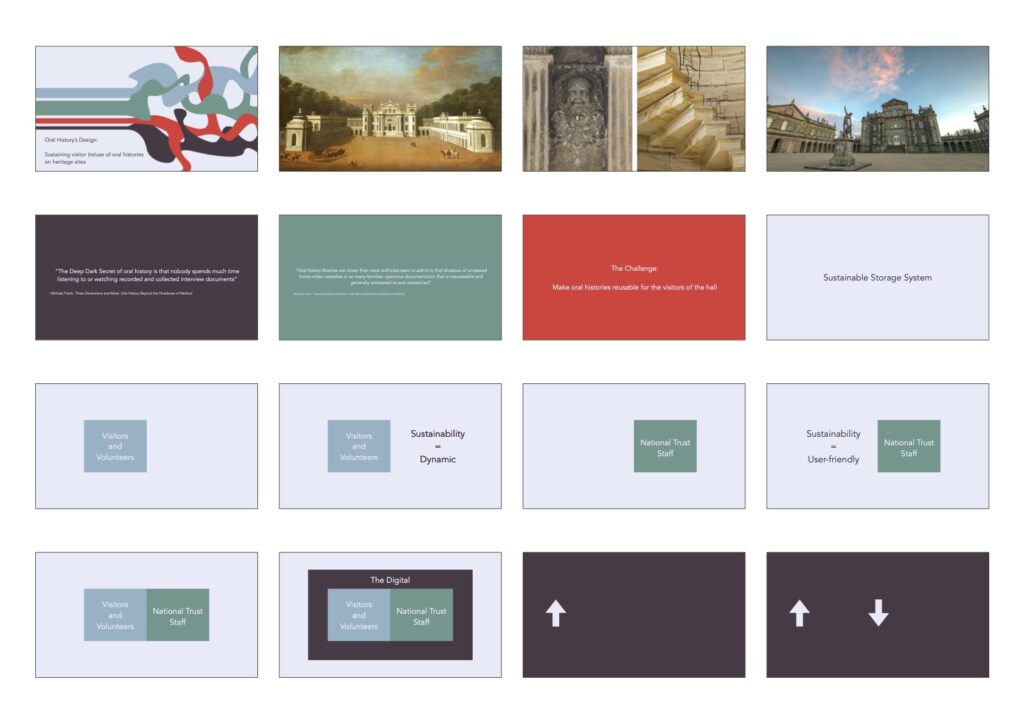

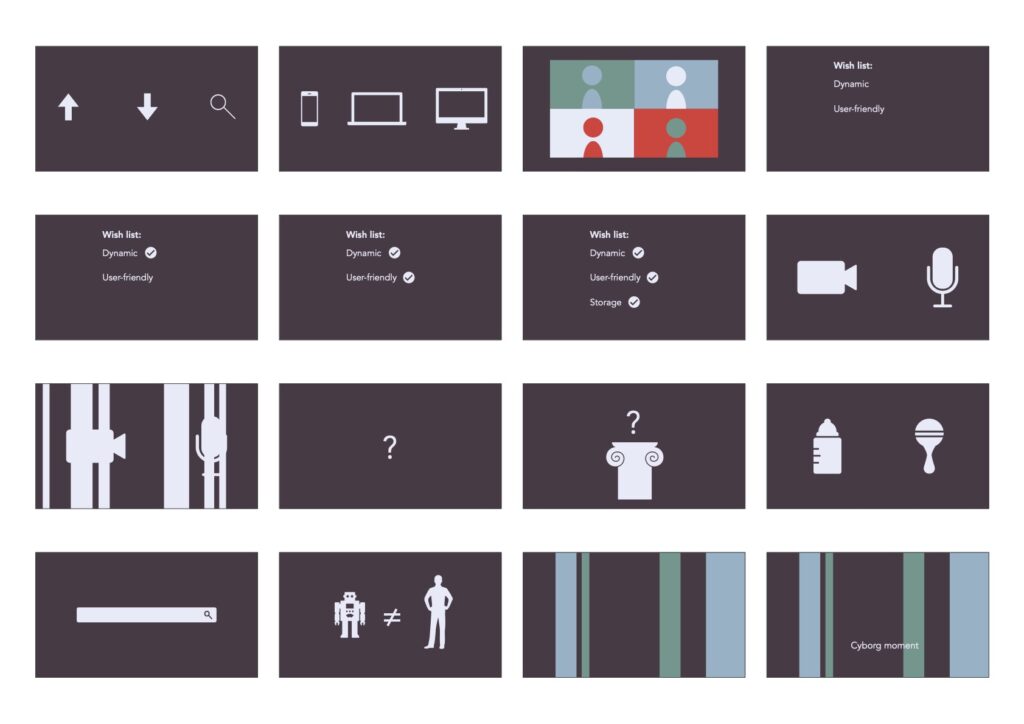

OHD_PRS_0125 Oral History’s Design: Sustaining visitor (re)use of oral histories on heritage sites

On 26 March I presented my first paper during a series of Digital Heritage Workshops organised by Lancaster University and IIT Indore. It was really scary and weird. I didn’t feel looked after at all. I also presented something that had already been discussed by previous speakers. Anyway you live and learn.

Script

This is Seaton Delaval Hall. Built in the 1720s the hall and its residents, the ‘Gay Delavals’ became renowned for wild parties and other shenanigans. In 1822 the hall went up in flames severely damaging the property. This history is represented very well in the collection that is housed at the hall which is now run by the National Trust.

What is less represented is the more recent history. The community that looked after the hall after it burnt it down, when it was a prisoner of war camp during both wars and later when the late Lord Hastings invited the local people to parties after its restoration.

This history lives within the local community. Luckily we have the wonderful field of oral history that allows us to capture this predominately undocumented history.

However oral history has a deep dark secret. After recordings have been made and analysed, they are locked into an archive or into a historians cupboard and never heard from again. They are like a box of unwatched home videos.

This in the context of Seaton Delaval hall seems sad as its strength as an institution lies within its deep connection with its surrounding area. It would therefore be a shame if the community who gave these histories cannot access them. I also personally think this to be ethical dubious as the lack of access to these oral histories brings up issues of power inequality where an institution like the National Trust happily takes the oral histories but not giving something in return.

SO this is the challenge: we want to make oral histories reusable for the visitors of the hall.

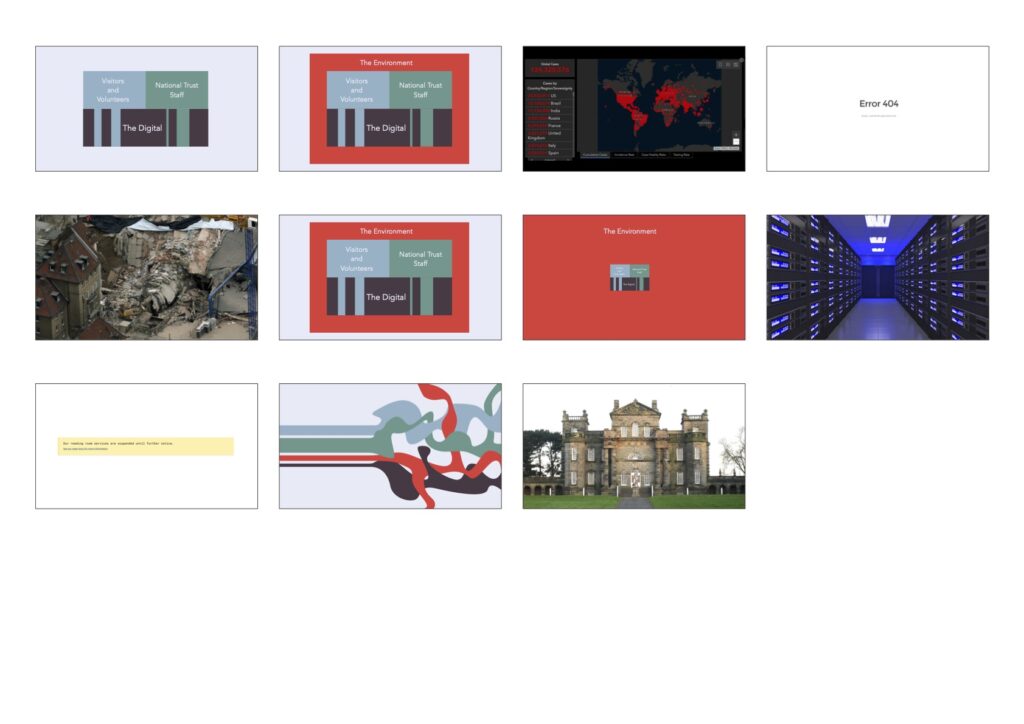

To make the rather complex problem more tangible I have focused in on the idea of sustainability:

I would like to point out here that I am using the term storage system instead of archive because I feel that the idea of the archive is very loaded and cultural represented as not particularly accessible to the masses.

Let’s start with the visitors and volunteers. This particular group, especially the volunteers, are the people who will contribute and donate their oral histories to the hall. Now because of the standard time and financial constraints the period of recording will not be able to capture all the stories. So this system that will house the the initial recordings needs to be dynamic and sustainable enough for the visitors and volunteers to keep adding and reflecting on the history.

For the staff the term sustainability addresses user friendliness. It needs to be easy for a new staff to learn how the system is use and managed.

This is where I believe the digital can help.

The digital as we are all fully aware has the amazing capacity to allow people from across world to upload, download, browse all sorts of content. It’s awesome. Also as time goes on more and more people are getting familiar with the digital sphere. Especially with the pandemic which forced to many use it more. This is not just individuals but also the case for most institutions notably those in the culture sector who have been very busy trying stay afloat by working out how they can use all these digital tools to keep their audience. The digital and its tools have become and are increasingly becoming part of everyday life.

The dynamic and sustainable requirement of the system, where people can easily add information and stories is pretty covered by basic digital systems.

The user friendliness can be achieved if the staff are involved right at the beginning with the design of the system. Allowing it to mould to the staff’s digital habits and knowledge.

What the digital can also help the staff with is storage. The digital is able to store documents in also sorts of formats and in all sorts of locations. I personally find that the internets ability to duplicate (think memes) might be a possible tool that could help storage issues but that simultaneously brings up all sorts ethical issues around permissions and copyright.

However what the digital also has done is created this desperate need to record and store everything and therefore also a huge sense of loss when something isn’t captured. Because as you are able to capture and store something you also create a whole bunch of things that arent captured and therefore lost. Technology has always played a huge role in this, just look at the field of oral history which relies completely on the ability to record someone’s voice. So then the question is should we record everything? Do we need to record everything? It’s tempting when you can record everything. But then you have everything and that is also useless because you cannot reuse everything. One of the archivists at the Parliamentary Archives once told me that they had calculated how long it would take for them and their colleague to digitise everything and it was 120 years. This paradox brings up issues around value. What do we value? Whose voices do we value? But an even bigger problem is what will we value?

This one of the bigger I imagine we will be dealing with in the next couple of years. Trying to keep the digital eco system healthy and not complete collapse under its own weight.

The digital is still very young. Which is proven by what it can do really enthusiastically like record everything and allow everyone to contribute. But it is also proven by the gaps that has. For example many search functions on online archives are difficult to use and don’t deliver that same serendipitous feeling that brick and mortar archive has. A search bar is not close to being the same as an archivist who knows the collection. Robots are not completely ready to replace humans just yet. For now humans will have to fill in the gaps that the digital has.

A good example of this blend of human and digital is that people who are unable to do their research because they cannot go into archives or the digitisation of the document they are interested in is not good enough. What I have seen many people do now is use their human network to access these documents by ringing people up and asking them take pictures of documents. I thought this was a funny cyborg-y moment where people needed both technology and a human person to achieve their goal.

So what we are looking at is how the digital can support the needs of humans at Seaton Delaval Hall by adapting to their needs. But at the same the humans are free and able to fill in these gaps that are present in the digital.

However there is one more layer I would like to add to this challenge of building a sustainable storage system. And that is the environment. Our environment heavily influences whether we can access archives. A pandemic can shut us off from the brick and mortar archives. A power cut can take down the servers where the digital archive stored. Or an earth quake or storm can destroy both completely.

This in addition to digital gaps is why I do not believe that it is sustainable to solely relay on either a digital or a brick and mortar storage system. A system that floats between these two worlds and at its centre has the humans that are reason for its existence, that I believe is the closest we might get to having something sustainable. Something that will allow Seaton Delaval Hall and its community continue telling stories for generations to come.

Slides

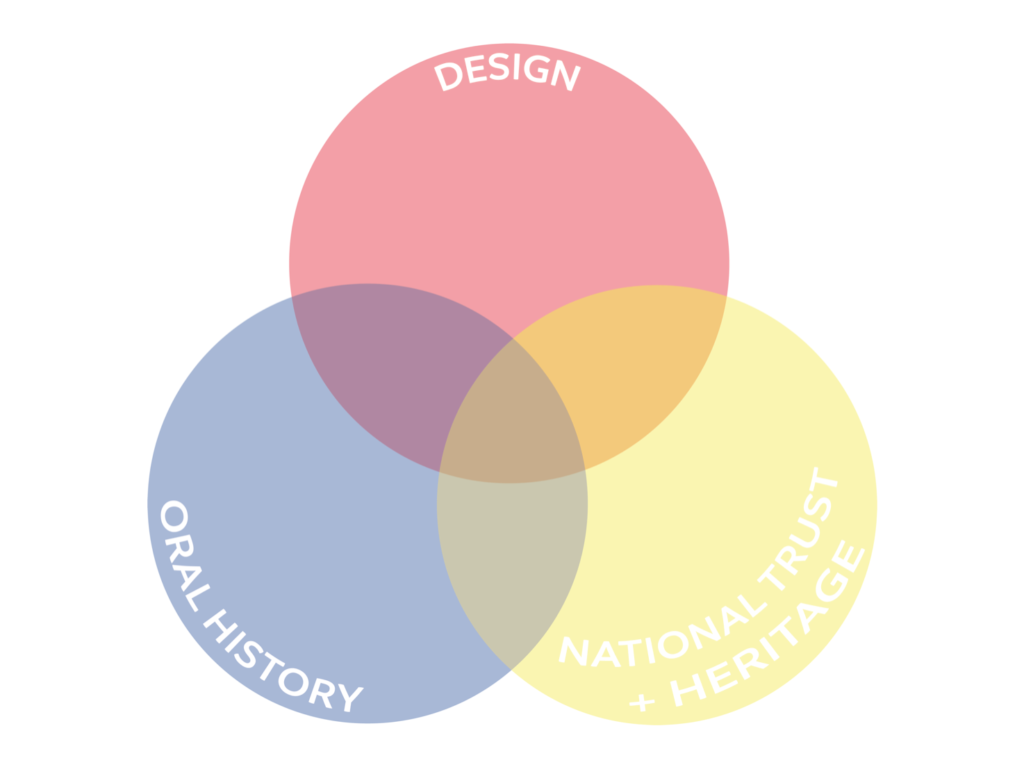

OHD_PRS_0124 Presentation/Interview

Below is the presentation I had to do in order to be chosen as the student to complete this PhD. The interview took place on Feb 18th 2020 and the question I had to answer was, “What are the key challenges and opportunities [in this PhD] and how will you address them?”

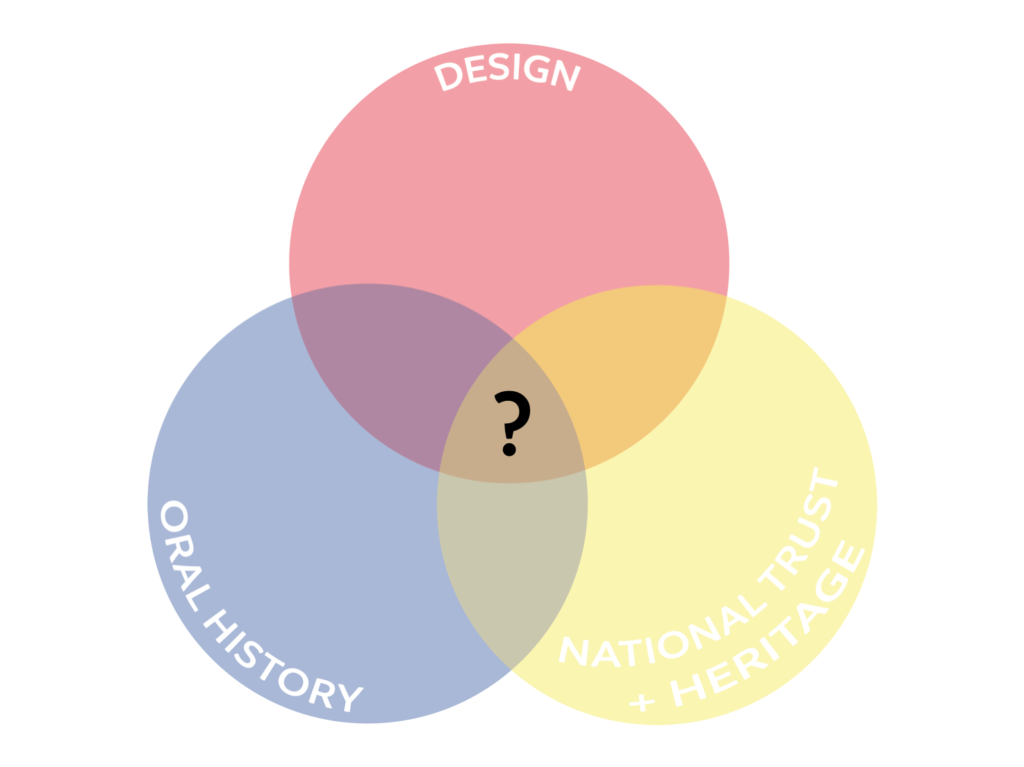

SLIDE ONE

I have set this presentation up as a Venn diagram of three main parties of this CDA: National Trust and the heritage sector, Oral history and Design. In order to answer your question, I will navigate through the various sections of the Venn diagram identifying opportunities, challenges and how will address them.

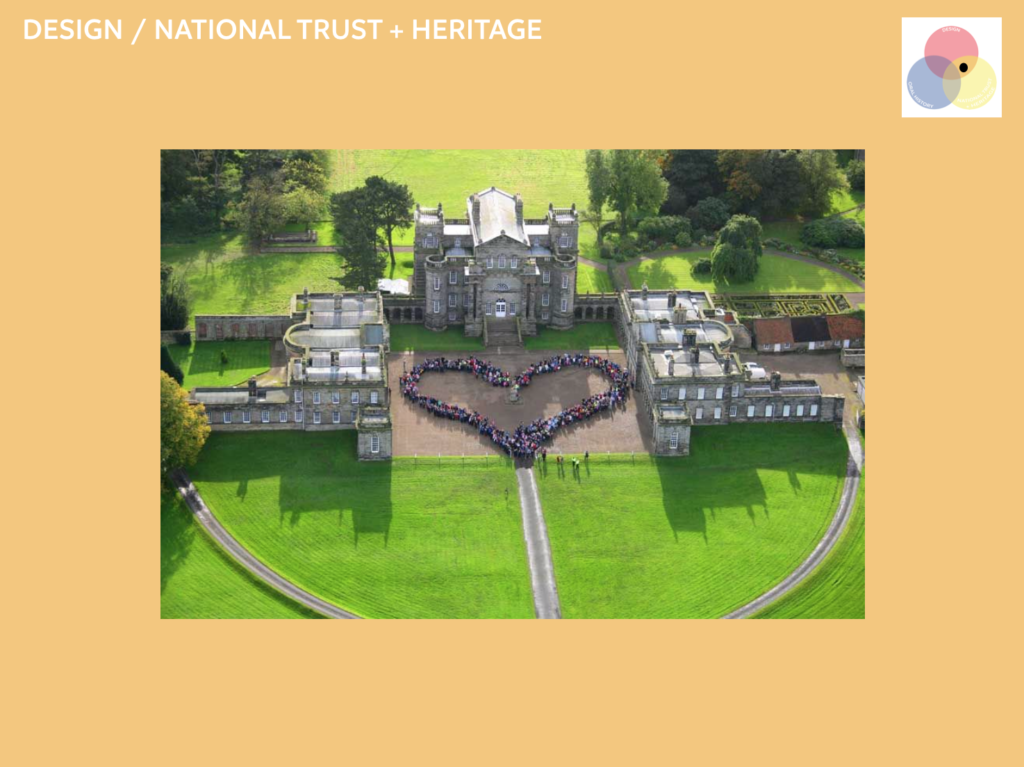

SLIDE TWO

I think the first opportunity lies with the National Trust property Seaton Delaval Hall. If you observe the setting and history of the Hall you will find it to be the appropriate setting for this CDA. Firstly, the Hall is in the middle of a wide and rich community. Over hundreds of years the Hall and its inhabitants have contributed to this community and return the community has also given back with the most recent example being the money that was raise to help the National Trust take over the property. Secondly, it is a relatively young National Trust property. By that I mean that it has only been acquired by the National Trust in the last 11 years, meaning that until very recently; stories, memories and histories were being made at the Hall. Seaton Delaval Hall is therefore a perfect candidate for any oral history project, however a recent collaboration between the National Trust and MA in Multidisciplinary Innovation at Northumbria University makes the Hall the perfect location for this CDA.

SLIDE THREE

In May 2019 as part of the Rising Stars Project the National Trust came to Northumbria University with hope to collaborate in setting up a new oral history project. I was part of the team on the Multidisciplinary Innovation MA that was given the challenge of creating a new, an innovative method for collecting, archiving and displaying oral history. We started off by investigating methods of collecting group memories, as at first we found the National Trust’s current prescribed method of collecting oral history too formulaic. We concluded that due to the aforementioned setting of the Hall there should be a focus on reengaging the local community through this oral history programme. So we wanted to create a more participatory type of oral history that reveal a bigger picture of the Hall and created a sense of collective ownership of these histories. Instead of the “rather odd social arrangement” of the one-to-one interview, as Smith describes it in Beyond Individual / Collective Memory: Women’s Transactive Memories of Food, Family and Conflict, the team wanted to lay the power of the narrative with the participants instead of the interviewer. What we wanted to avoid is what the historian Lynn Abrams experienced while working on a project about women’s life experience in the 1950s and 60s. During that project she found that her position as an expert in women’s and gender history and implied feminist meant that her participants adapted their story to fit the wider feminist narrative. However, as our project progressed and the team dove further into oral history theory we started to understand the importance of individual interviews. Especially because during the testing of our group interviews we found that some people were less comfortable with the group setting and therefore would contribute less.

SLIDE FOUR

So, after three months of research, designing, testing, refining and testing again we developed two new group-interview methods alongside an incorporated individual interview. We also created several ways to display oral histories around the property, and potential new methods of archiving oral histories. Despite the high level of outputs the project only really scratched the surface, however it gave the opportunity for this CDA to exist in the first place. I view this project as the launchpad for this CDA. What it did was start an exploration into collective ownership and the role of community within the context of oral history at Seaton Delaval Hall and it brought together the various parties sitting here today. But most importantly it revealed that it would require more time and effort for it to be successful. This is especially the case with archiving, which was purposefully left open ended by the team, because as we producing all the previously mention outputs we discovered that oral history archiving is a very difficult problem.

SLIDE FIVE

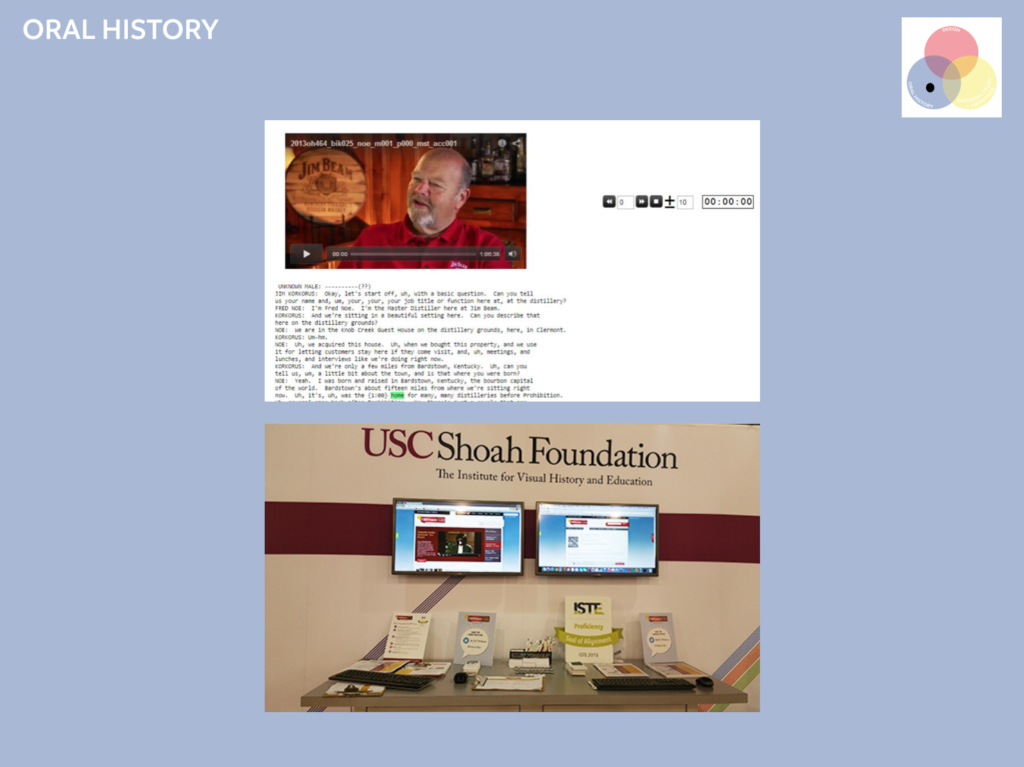

Micheal Frisch discusses difficult problem this extensively in his paper ‘Three Dimensions and More’. He describes oral history archives as a shoebox of unwatched family videos and outlines various paradoxes that occurs in oral history archives. One of the paradoxes, the Paradox of Orality, refers to the inappropriateness of the reliance on transcripts in the context of oral history. Many oral historians, including Alessandro Portelli, agree that using transcripts in archiving reduces and distorts what was originally communicated by the interviewee. Although there are many archives that rely on transcripts, there are also archiving systems being developed that tackle this exact issue. Certain systems are already engaging with this paradox by using various forms of technology. Such as the Shoah Visual History Foundation, set up by the film director Steven Spielberg, where video testimonies of holocaust survivors are indexed, timestamped in English and can be navigated along multiple pathways. Another example is Oral History Metadata Sychronizer (OHMS) created at the Louie B. Nunn Center for Oral History at the University of Kentucky Libraries, which can be navigated by searching any word and it will jump to the exact moment that person is talking about the searched word (Boyd). I imagine throughout the CDA these systems, including the more analogue archives need to be explored further in order to uncover the opportunities for innovation. What we are specifically looking for is the opportunity to create a system that is not driven by technological advancements, but by a desire to change the culture of how we use archives.

SLIDE SIX

Currently, we use all types for archives in a static way, which is the opposite to how we treat history. Not only are we constantly making new history through the passage of time, our attitudes towards history constantly changes. For example the global discussion surrounding artefacts in the British Museum or even attitudes towards mining. Recently I worked with the arts and education charity Hand Of at the Durham Miners Hall with children from the local area. Working with these children you see that they view mining through a completely different lens to the generation that came before. While you and I might associate mining with the miners’ strike and the deindustrialisation of the UK, these children view mining as something from the pass, something important to the previous communities but ultimately something unsustainable and bad for the environment.

The static nature of the archives is in complete contradiction to how people experience history. I believe this CDA is looking for is a more sustainable and dynamic preservation of stories. A system that taps into the ever changing zeitgeist reflected in its visitors instead of keeping everything frozen in time.

Well the CDA is called the ‘Oral history Design’. In my eyes I see design the provider of tools for exploration, with Seaton Delaval Hall providing the test subjects. This CDA would not be possible if it was not for the resources that the National Trust has to offer. Those resources being the visitors, the volunteers, those who provide the histories and the team working at Seaton Delaval. I believe that in order to create a system that is truly sustainable it needs to be tested at every point of the process and the collaboration with the National Trust gives us that opportunity.

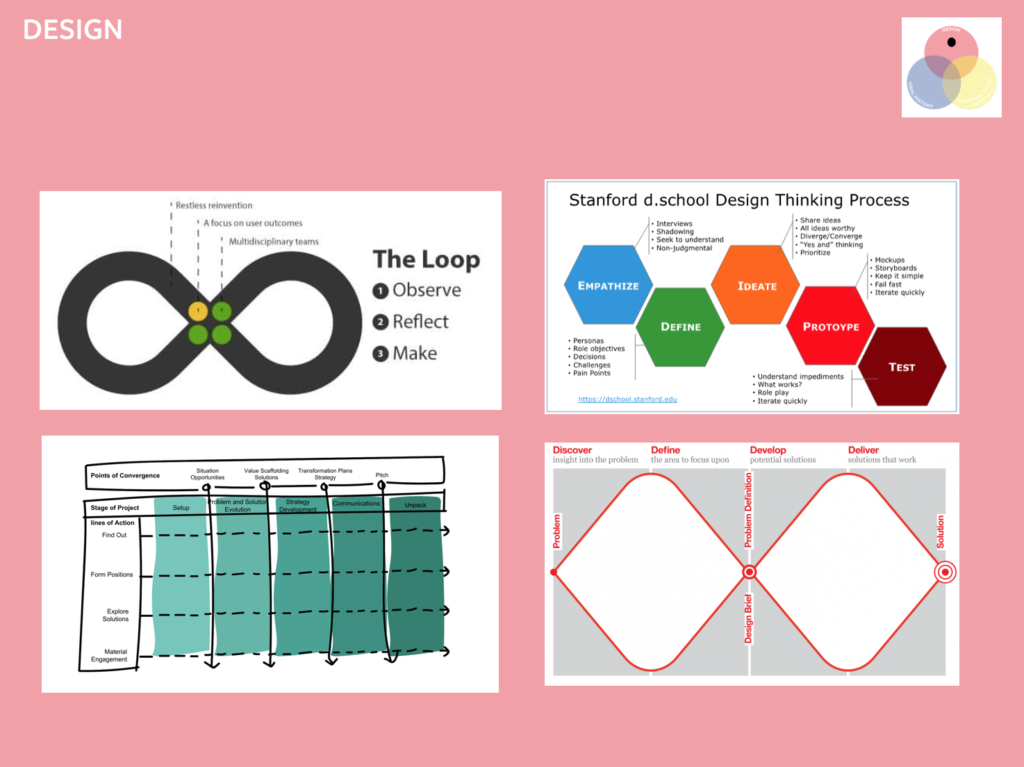

SLIDE NINE

The challenge however is finding the appropriate design tools. Design intervention and the use of design thinking tools can deliver high rewards but it can also cause considerable damage if not use responsibly. Not only do I expect to do more research into design methods on top of the ones I am already familiar with. I also expect to constantly be reviewing, adapting and modifying the tools and design process as project progresses. This is something that is highly encouraged by many people in the field of including the Kelley brothers, from IDEO, who openly invite people to adapt their methods and Natascha Jen from Pentagram, who argues that design thinking is more of a mindset, not a diagram or tool. Within this CDA this might evolved into regular reflection on the process both from myself as the student and from the other parties involved. All of this is especially important because the collaboration between design and oral history is a relatively new and unexplored territory.

SLIDE TEN

This unexplored territory, however gives the CDA opportunity to explore something in addition to the creation of a new archiving system; the methodology behind cross-disciplinary work within the academy. Cross-disciplinary work is nebulous and struggles to be categorised within the academic system. As I found throughout my MA there is a lot literature that talks about interdisciplinary, transdisciplinary, multidisciplinary, cross-disciplinary work. These papers, books and articles talk about bringing various parties together in order to solve a problem but it is nearly always in the context of business or social enterprise. The CDA will therefore offer us the opportunity to research and experience multidisciplinary or cross-disciplinary work within the context of a university.

However, cross-disciplinary, transdisciplinary, interdisciplinary, multidisciplinary work, whatever you would like to name it, does come with its fair share of challenges. I am familiar with this as during my MA I had to work in an 18-strong team of people from a diverse range of ages, ethnicities, nationalities and socio-economic backgrounds and different fields of work. Throughout the year it was clear that one of our biggest barriers was communicating across these differences. It often felt like I was speaking a completely different language, which sometimes was the case, as certain ambiguous words were perceived differently depending on the person’s background. I predict this to happen throughout the CDA, not only across the design and oral history but also with the National Trust and any additional parties that might be involved.

SLIDE ELEVEN

It is essential that we have as many of these cross-disciplinary conversations as possible. Roberto Verganti, in his book Design-driven Innovation, refers to these types of cross-disciplinary conversations as a ‘design discourse’ – experts from different backgrounds exchanging information. Verganti finds this to be essential in design-driven innovation, an innovation strategy that pursues change through a reinvention of the meaning of a product or system instead of relying of technology. Which is exactly what this CDA is looking for.

This design discourse needs to be managed and organised efficiently, which I feel confident I am capable of doing due to working in teams throughout my professional and academic work. Especially thanks to my MA and my work with Hand Of and teaching for the early English programme Such Fun! I know the importance of clear communication and disciplined organisation. I imagine that I as the student of this CDA, I will have to take a project manager-esque role in order to float between the different disciplines, communicating progress and finally managing expectations.

SLIDE TWELVE

And that really is the crux of it all, managing expectations, because you cannot guarantee anything. For all we know the answer to design oral history archives is – don’t, National Trust’s prescribed archiving method of electronic cascading files does the job perfectly well. For now this CDA is exploring the unknown, but that is what I like about it. I spent three years in a Goldsmiths art studio exploring the unknown, then I did an MA do to more targeted exploration of the unknown and now I have a narrow it down again in applying for this CDA. Exploring the unknown is full of opportunities and challenges, but you have to do it in order to find them and I very much like to do it.

The feedback a got on my presentation was good, however I did not do as well on answering the questions. This is a completely fair judgement as I felt slightly unprepared. I think it is important that I start planning out the steps I will be taking throughout the three years and deadlines for certain outputs.

OHD_LST_0123 questions

Here is a collection of questions I have asked myself concerning the topic of my PhD both big and small.

How do we handle the racism that exists in the archives? Date: 16/06/2020

What do we do with unused interviews? Date: 19/06/2020

Do we need to reevaluate how we create oral historians in order to ensure more equality within the sector? Date: 16/06/2020

What is the difference between a documentary and an oral history project or article? Are they not both curated equally? Is the only true form of oral history stuck unedited in the archives? Date: 20/07/2020

How can we utilise Gen z and the digital natives in oral history archives? What might the pitfalls be? Date: 21/07/2020

Do I have a problem with the word history in the context of oral history interviews? Date: 21/07/2020

Are there any aural oral history papers? If so where are they and why aren’t there more of them Date: 01/10/2020

How does the archive function in a ‘knowledge/data’ economy? Date: 23/10/2020

Do filters for the public limit or increase accessibility? Date: 23/10/2020

Are we looking for an ‘archive’ or a completely new system? Date: 23/10/2020

What should an archive be like during an pandemic? Date: 08/02/2021

How does “Material History” work in the context of oral history? Date: 08/02/2020

Do we get bogged down in the ethics? Date: 16/02/2021

What is our relationship to the ‘public’? Date: 16/02/2021

What does digitization replace? Date: 10/03/2021

Are result lists the problem when it comes to searching? Date: 12/02/2020

What does it mean if people can’t remember? When people are scared of not being able to remember? Date: 16/03/2021

Where does intertextuality and oral history theory end and academic snobbism begin? Date: 16/03/2021

Is having an oral history recorded like donating your body to science? Date: 16/03/2021

What do the interviewees think about reuse? Date: 16/03/2021

How do we take stuff back to the interviewee? Date: 16/03/2021

How do you build a community? Can you build a community? Or do they only grow naturally? What is the balance between setting up/designing a community and having one naturally occur? Date: 30/04/2021

Can the digital ever be transparent if those who make it are from one exclusive group? Date: 11/05/2021

Do we trust archives? Date: 11/05/2021

Does our idea of original need to change? Date: 11/05/2021

Can you democratise history outside of a democracy? Date: 07/05/2021

OHD_PRS_0122 Staying flexible: how to build an oral history archive

The second conference paper I presented. This one went better than the first one so that is positive.

Slides

Script

[slide two]

This is Seaton Delaval Hall. This National Trust property can be found in Northumberland just up the coast from Newcastle. Built in the 1720s the hall and its residents, the ‘Gay Delavals’ became renowned for wild parties and other shenanigans.

[slide three]

In 1822 the hall went up in flames severely damaging the property. This history is well represented in the collection that is housed at the hall.

[slide four]

What is less represented, however, is the hall’s more recent history: the community that looked after the hall after it burnt it down, the prisoner of war camps, and the medieval themed parties that the late Lord Hastings threw after the hall’s restoration.

For my PhD I will attempt to solve this issue of missing history by building an oral history archive. Oral history is a tool that has been employed many times to help represent the underrepresented in history. The challenge however is to build an archive with these oral histories. To help me explain how I am approaching this challenge I will use a metaphor.

[slide five]

This is a Ferrero Rocher. Through this yummy treat I will attempt to explain my project and the various layers of the process that need to be considered and analysed in order to be able to build an affective oral history archive.

[slide six]

The Hazelnut AKA a new storage system

The metaphorical hazelnut and core of this project is this storage system that will hold the oral histories I record. Why do I call it a storage system and not archive? I say this for three reasons, firstly because archives and oral history recordings are not the best of friends.

[slide seven]

The original framework that we use to structure and build archives is, and has always been, based around archiving mostly written documents. Searching through this type of material is easy because their content is visually apparent. These days you can, if they have been digitise, word search the documents very easily.

[slide eight]

Oral histories recordings (not the transcripts) struggle to fit into this framework, because their content can only be accessed if you sit down and listen to them. Listening back to these recordings can take a lot of time and can be hindered by outdated technology. This mismatch between the material and the place where it is stored often discourages people to reuse oral histories.

[slide nine]

I think the oral historian Micheal Frisch puts it best when he called oral history archives “a shoebox of unwatched home videos.” The content is there but the viewing a specific moment is an arduous task. Mining the hall’s community for stories and throwing them into a shoebox is exactly what I want to avoid with this PhD.

[slide ten]

At Seaton Delaval Hall I want to create a storage system that broadens access to and actively encourages reuse of the oral histories, in order to support the community that has looked after the hall for so many years.

The second reason I say storage system instead of archive is ….

[slide eleven]

because currently archives are struggling with adapting to advancing technology. In recent years there has been a push to digitise archives with the COVID-19 pandemic giving this process an exceptional boost.

[slide twelve]

However, this digitisation requires a lot of resources like money, time and manpower that many archives, especially smaller ones, simply do not have.

[slide thirteen]

In addition, what this push to digitise does, which it does in many sectors, is attempt to replace a human with a robot, who in my opinion is simply not up to the task. Typing into a search bar is not the same as asking an archivist for help.

[slide fourteen]

While a search bar is a tool one uses when researching, the archivist becomes a fellow researcher, making room for far more flexible and creative exploration.

[slide fifteen]

Thirdly, archives are rather static in comparison to the world outside of their brick and mortar walls.

[slide sixteen]

Especially in the last year there has been increasing pressure to review how we present our history as a society. This dynamic debate is not reflected in the way we store our historical documents.

[slide seventeen]

This limited reviewing and updating of our archives actually makes it harder to do research. The most obvious instance being how certain keywords become outdated over time, which is something that is especially prominent in the archiving of minorities’s histories such as LGBTQA+ and Black history.

[slide eighteen]

The way we traditionally build an archive does not fit with contemporary society. Archives were initial set up to preserve one view of history in one type format. They did not leave room for new technologies and new points of view. Now, archives are attempting to change this by rather awkwardly moving into the digital space without truly questioning how these digital tools affect the archiving process and researching in archives.

In order to create a new storage system I wish to let go of these traditions, these symbols and languages that we use to navigate oral histories, archives and the digital.

[slide nineteen]

I want to start with a blank canvas and build a storage system that not only reflects the technology and views found in society but also makes room for any further developments in these areas. Now, the next question is: how we might go about building this new system?

[slide twenty]

The chocolate filling AKA working together without killing each other

[slide twenty-one]

AKA collaborating! A truly fabulous buzzword that works very well in funding applications but in reality is really difficult to do. Why? Well, every field of research has its own type of

[slide twenty-two]

‘disciplinary upbringing.’

[slide twenty-three]

When I say ‘disciplinary upbringing’ I am referring to the lens that each field views things like language and methods of work through. In other words the

[slide twenty-four]

‘here we do things this way’ attitude.

[slide twenty-five]

When people collaborate across disciplines they bring this lens, this disciplinary upbringing, with them so when the work starts everyone is viewing the challenge through separate and different lenses. This can lead to a lot clashes and plenty confusion.

So how do you solve this?

[slide twenty-six]

You could just say that people should leave their disciplinary upbringing at the door but that never works.

[slide twenty-seven]

Instead I intend on using these disciplinary upbringings to the advantage of the creative process by encouraging people to be open about them and in some cases even exaggerate them a bit. What this does is bring to light the various

[slide twenty-eight]

‘creative tensions’ that are present in the collaboration.

[slide twenty-nine]

For example in the context of this project where we have a collaboration between the fields of oral history, design and heritage you can find many creative tensions that are the consequence of differing disciplinary upbringings.

[slide thirty]

Between oral history and design there is the tension of the medium of communication; historians like writing and designers love a good visual.

[slide thirty-one]

I can tell you from experience that design and heritage work at dramatically different speeds. One of design’s key philosophies is “fail fast”, which is definitely not something would be mentioned in a National Trust meeting.

[slide thirty-two]

Finally, between oral history and heritage we find possibly the most challenging of creative tensions, which is differing opinions on the representation of history.

[slide thirty-three]

It is important to identify these creative tensions because they highlight issues that might have otherwise gone unseen if everyone had just been polite and kept their mouth shut.

[slide thirty-four]

Once they have been determined they function as a great source of information. This information needs to be drawn out through thorough questioning. It is essential to discover why the tension exists and how it might inform the creative process.

[slide thirty-five]

This does however mean that sometimes you might have to ask what seem like silly and obvious questions, because your disciplinary upbringing to begin with blocks you from fully understanding where other people are coming from. To complete the questioning to its fullest potential it is necessary to unpack any confusion no matter how small or trivial they might seem.

[slide thirty-six]

However the most fundamental thing within this chocolate filling of collaboration is — listening. One must always remember that you are not there to defend your disciplinary upbringing, you are there to solve a collective problem. When identifying and questioning creative tensions everyone must listen to all of those collaborating.

[slide thirty-seven]

Overall the chocolate filling represents something that can be very difficult, but with open minds, questioning and listening can be exceptionally fruitful.

[slide thirty-eight]

The Crunchy shell aka beyond the toolkit

A Ferrero Rocher is not complete without its crunchy shell and neither would this project. The crunchy shell in this context represents the legacy of the project. It is important to me that the project and the storage system does not end with the completion of this PhD.

[slide thirty-nine]

In order to avoid this I and everyone involved in the project shall thoroughly question and analyse the process of building this storage system. We need to reflect on what worked and what didn’t work. This questioning needs to be beyond which workshop activity was fun and whether we had enough time.

[slide forty]

What we need to do is extract questions that will help someone else set up a similar project. So instead of creating a rigid set of instructions with painfully particular processes, we offer future oral history projects questions that they must ask themselves before, during, and after the project. This hopefully will allow them to adapt the process to their needs and encourages them to think more creatively.

[slide thirty-nine]

Conclusion

Now I completely recognise the irony of me slamming the idea of a rigid sets of instructions and then ending on a how-to guide, but in my defence I had the title before I fully wrote the paper so please forgive me.

How to build an oral history archive

- Let go of your preconceptions of what an archive is (and also what the digital is)

- Work together by allowing creative tensions to occur and be questioned

- Reflect on your process and extract questions for future projects

The true aim of this how-to is to make sure that we do not end up in the same position we are now, where our archives no longer reflect society. The world is only going to get more complicated so if we do not leave room for questioning and change, archives are always going to be behind. This would be a disaster as archives on a macro scale are the keepers of our history and (in theory) hold the foundations of our collective identities as a people. On a more micro scale I have personally always found comfort in how archives keep documents that show everyday humanity, like a postcard to a fellow artist or a writer’s note to a partner.

So here is my how-to on making an oral history archive. Take it with you, try it out, tell me if it worked. I am going to do the same and probably change it many times in the next three years.

OHD_WRT_0121 the code/manifesto

The manifesto below is based off Meirle Laderman Ukeles’ Manifesto for Maintenance Art.

This the code of ethics outlined in by Mike Monterio in Ruined by Design. I am using this as a base for my code of ethics for this project. I have written a summary of each rule and then written in the green text how I might fulfil it.

A designer is first and foremost a human being.

Designers work within the social contract of life. Within their work they need to respect the globe and respect fellow humans. If their work relies on the inequalities in society they are failing as a human and a designer.

This project risks becoming a completely digital affair, which can be alienating to some in society, especially the elderly who make up the majority of this project’s audience. Another large responsibility is making this an eco friendly venture, which in my opinion is essential but not easy.

A designer is responsible for the work they put into the world.

The things designers make, impact people’s lives and have the potential to change society. If a designer creates in ignorance and does not fully consider the impact of their work, whatever damaged then is caused by their work is their responsibility. A designer’s work is their legacy and it will out live them.

This is where I think an oral history project about this project will encourage an awareness around the impact of the design. If one of the first things the archive designed houses is recordings of those would built it, it will show confidence in the work. The legacy of the project will live within the outcome of the project.

A designer values impact over form.

Design is not art. Art lives on fringes of society, design lives bang in the middle of the system of society. It does NOT live in a vacuum. Anything designed lives within this system and will impact it. No matter how pretty it is if it is designed to harm it is designed badly.

Nothing a totalitarian regime designs is well-designed because it has been designed by a totalitarian regime.

M. Monterio ‘The Ethics of Design’ in Ruined by Design

Let’s make it inclusive before we pick out the font. This is especially a rule for me, a former artists.

A designer owes the people who hire them not just their labor, but their counsel.

Designers are experts of their field. Designers do not just make things for customers, they also advise their customers. If the customer wants to create something that will damage the world it is the designer’s job as gatekeeper to stop them. Saying no is a design skill.

The team at the National Trust and the oral history department are (relatively) new to the world of design so it is my job to help them navigate this rather messy world.

A designer welcomes criticism.

Criticism is great. Designers should ask for criticism throughout the design process not only to improve the thing being designed but the designer’s future design process.

Now that I am working between three different parties it is essential that I keep communication open at all ends. The more the merrier attitude must reign.

A designer strives to know their audience.

A designer is a single person with a single life experience, so unless they are designing something solely for themselves they probably cannot fully comprehend complexity of the problems their audience is facing. Therefore it is designers’ responsibility to create a diverse design team, which the audience plays a big role in.

This collaborative project is perfectly set up the fulfil this, as long as COVID-19 does not get in the way.

A designer does not believe in edge cases.

‘Edge cases’ refers to people who the design is NOT target at and therefore cannot use. Designers need to make their design inclusive. Don’t be a dick.

The National Trust has a very particular audience which in some design projects would make them edge cases. In this project I think I need to look at how people with disabilities would use the archive and people who are not native to digital technology.

A designer is part of a professional community.

Each individual designer is an ambassador for the field. If one designer does a bad job then the client will trust the next designer they hire less. It also goes the same way, if a designer refuses to do a job on ethical grounds and then another designer comes along and happily completes the job, then the field becomes divide.

This collaboration between Northumbria University, Newcastle University and the National Trust has the potential to be the start of a series of collaborative projects. It is therefore my responsibility to ensure a positive working relationship with all involved. I need to be aware that I am an ambassador for all the institutions involved.

A designer welcomes a diverse and competitive field.

A designer needs to keep their ego in check and constantly make space for marginalised groups at the table. A designer needs to know when to shut up and listen.

I want to invite everyone to the party. Because the collaboration I have access to all the experts at the university but also at the National Trust. And each institution also has a huge and diverse group of people who can help influence and criticise the work. Think MDI and the volunteers at Seaton Delaval Hall.

A designer takes time for self-reflection.

Throwing away your ethics does not happen in one go, it happens slowly. Therefore constant self-reflection is essential. It needs to be built into each designer’s process.

I started doing this during MDI so now I can build on it. Maybe this website can help me reflect by holding all my thoughts. I should probably also timetable in moments of reflection from the off.

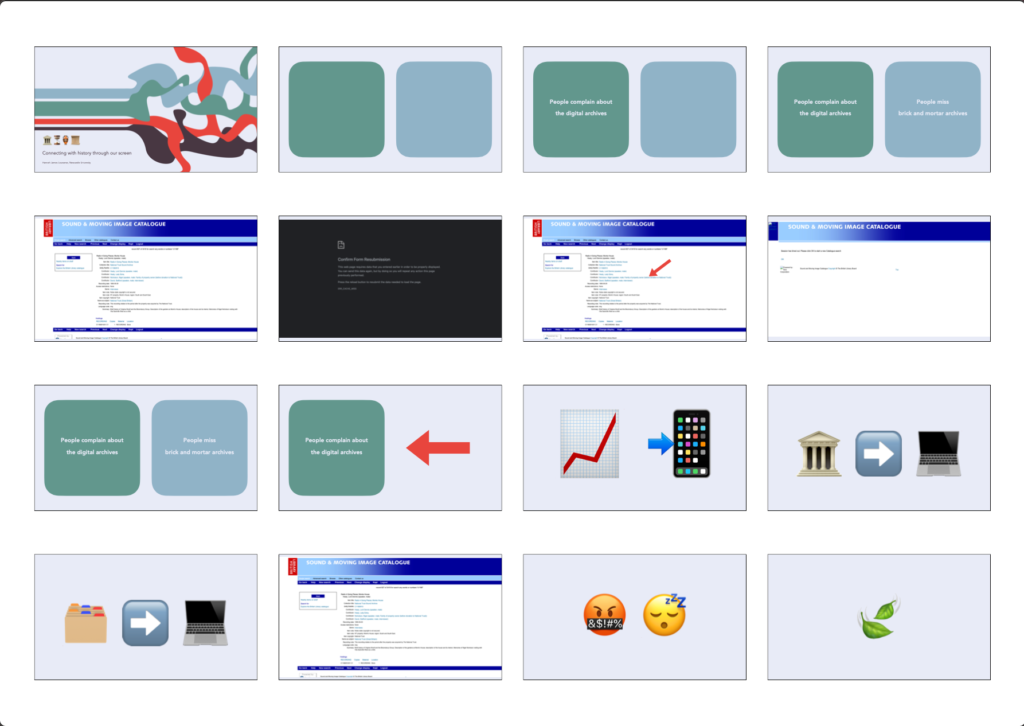

OHD_PRS_0118 🏛⏳🏺📜: Connecting with history through our screen

This was not a very good paper. I was very busy and I did not put my whole heart in it, which is always a shame. But a learning moment to remember to plan these things better

Slides

Google Gemini Summary of OHD_PRS_0118 - Connecting with history through our screen

[generated 06 / 01 / 2025]

Challenges with Existing Digital Archives: You effectively critique current digital archives, highlighting their limitations in capturing the serendipity and emotional connection often associated with physical archives. Issues such as clunky interfaces, limited search functionality, and the loss of contextual information are identified.

The "Archive-Robot" Metaphor: This is a novel and insightful perspective. By framing digital archives as "archive-robots" still under development, you emphasize the need for ongoing refinement and improvement. It shifts the focus from simply replicating physical archives to exploring new possibilities for digital interaction and engagement.

The Importance of Human Connection: You emphasize the importance of human interaction and the emotional connection to physical archives. You highlight the limitations of purely digital experiences and the need to consider the social and cultural contexts of archival research.

Ethical Considerations: You raise important ethical concerns regarding data privacy, digital inequality, and the environmental impact of digital technologies.

A Call for Innovation: You advocate for a more human-centered approach to digital archives, emphasizing the need for creativity, collaboration, and a willingness to experiment with new technologies and methodologies.

Key takeaways for your PhD research:

Focus on User Experience: Design digital tools that are intuitive, user-friendly, and enhance rather than hinder the research experience.

Embrace Collaboration: Foster close collaboration between oral historians, archivists, technologists, and community members throughout the design and development process.

Prioritize Sustainability: Consider the long-term sustainability of digital technologies, including maintenance, data preservation, and environmental impact.

Explore Innovative Approaches: Experiment with new technologies and methodologies, such as AI and machine learning, while also recognizing the limitations of technology and the importance of human interaction.

Overall, this presentation demonstrates a strong understanding of the challenges and opportunities presented by the intersection of oral history, technology, and heritage management. Your insightful observations and critical thinking will undoubtedly be valuable assets as you embark on this exciting research journey.

Script

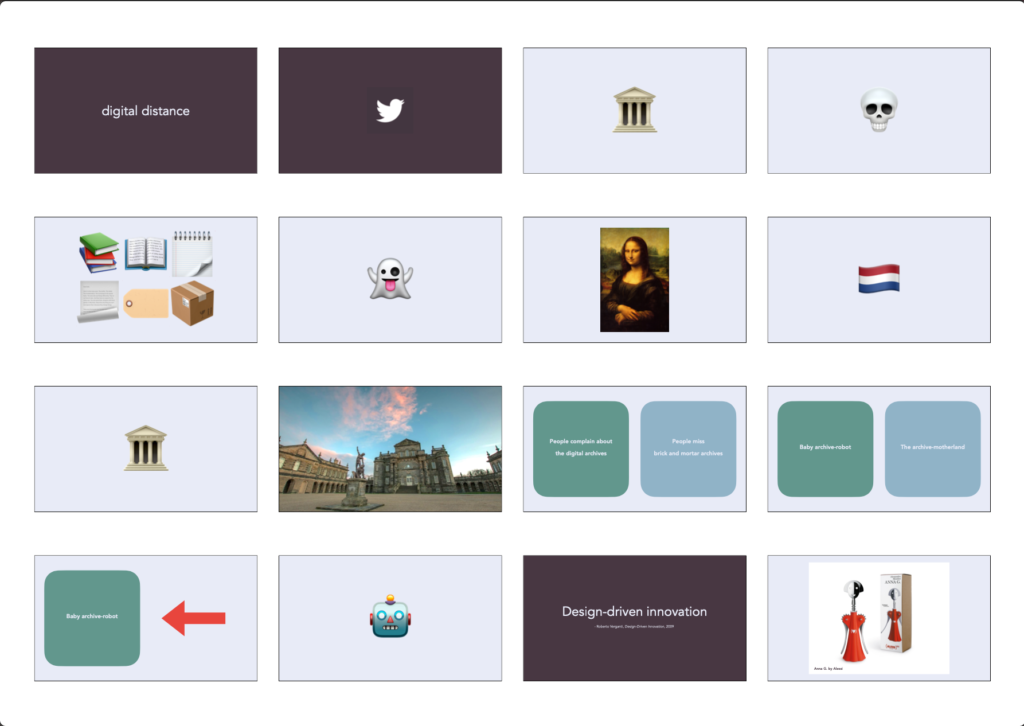

Since the start of my PhD in January there are two things I have observed when people talk about archives during COVID.

- People complain about the digital archives

- People express how much they missing brick and mortar archives

I, too, hold these opinions. I have recently started digging through the National Trust’s oral history archive which is housed at the British Library and it has not been the most relaxing affair. Every time I clicked on an entry and then wanted to go back to my search results I would have to refresh my page and if I accidentally clicked on any of the names that were hyperlinked in the entry pages I would lose my place in the archive and have to go back to the start. I also have very little experience of actually working in an oral history archive so really need to visit a brick and mortar archive that houses oral history. The only information I do have on listening to oral history in a brick and mortar archive comes from my friend who told me in horror how they had given a CD player and a broken set of headphones.

What I am going to do for this presentation is dissect these two observations and explore how I can reframe these in order to use them in my work for my PhD.

Point 1!

Let us start with the digital archives that so many of us have had to rely on over the last year. Digital archives exist because they are following the bigger trend of moving our lives online. But this move from brick and mortar to digital is about a literal as it can get. When I was going through the National Trust’s oral history archive it felt as if the British Library took the index cards that accompanied the recordings and just transcribe them into a webpage. They moved the collection online without thinking about how this new realm could enhance the experience of archive. Other than the fact that this makes going through the archive a bit frustrating and boring you also lose that serendipity that everyone always talks about when they are in brick and mortar archives: the scribble in the margins, the note lost in the pages of a book. These two things: the loss of serendipity and the direct translation is why I believe people are complaining.

So how do we solve this? To start with I suggest a reframing of what we think a digital archive is. As I previously mentioned a digital archive is not the digital equivalent of a brick and mortar archive because we lose that serendipity that we love so much. So what if we view the digital archive as a tool to access the information in the brick and mortar archive. Our computers, browsers and webpages then become the tools that grant us access to the archive, which is a role normally held by archivists. They are the people who usually accompany us in our journey through the brick and mortar archive. But our computers, browsers and webpages are not the same as a fully trained archivist. An archivist is a human who is capable of complex and creative thought. They can solve problems and navigate around barriers, while a computer is only as creative as its database and code allows it to be. So we could view digital archives as a digital alternative to archivists but I believe this would still cause frustration, because within this framing we are still comparing the new digital archives to the old brick and mortar archives and in this fight the brick and mortar archives have the creative upper hand (for now.)

So I would like to propose another way of framing our digital archives. A couple of weeks ago I attended a seminar on AI. During the seminar, Professor Irina Shklovski from the University of Copenhagen presented a paper called AI as Relational Infrastructure. She discussed how the way we view AI is all wrong. We view AI as a tool we can used but Shklovski suggested that we should view it as a relationship, an exchange of skills and knowledge. So I translated this principle onto my work in the National Trust’s oral history archive. This translation made me view my computer, the browser and this British Library portal as an archive-robot that was trying to help me navigate the messiness of the brick and mortar archive on the other side of my screen. However this archive-robot is very new to the archive; we need to remember that digital archives are the new kids on the block and these archive-robots do not know the ways of the archive yet. The way that I currently picture this relationship is as follows. Here we have our archive-robot who has just started their new job at the archive, they do not really know what they are doing, they might have even lied a bit on the CV. Along come a lot of random people who start handing all their documents, notes, and other bits and bobs over to the archive-robot, who and I cannot stress this enough has no idea what they are doing, and expects them to just sort everything out. This is a rather tall order as we already know that archive-robots cannot think as creatively as a human-archivist – yet. What we need to do now as a community that uses these archives is train these new kids in archiving because in the end they will help us in our research.

I know this sounds like I am advocating robot rights. Maybe I am a bit but what I really trying to say is that instead of viewing digital archives as the digital equivalent of brick and mortar archives, or viewing them as tools to access those archives, you can view them as an archive-robot who is trying to adapt to this new world as much as you are. It might sound like a silly idea but I can tell you from experience it eases the frustration a bit. And most importantly if we view our digital archives like this we put ourselves into a mindset that allows us to seek progress and development in our digital archives and not just settle for this rather crude translation of brick and archives. Digital archives are still in development and I think that if we see them more like archive-robots in training then maybe we can help them help us.

Point 2!

People miss brick and mortar archives. Other than the fact that we don’t really like digital archives right now, I think there is something deeply emotional about people’s desire to reenter brick and mortar archives. Even though we might have access to certain documents online, people still want to be near the physical document. Just like how people travel to see the Mona Lisa despite the fact that everyone knows what the Mona Lisa looks like. This feeling, this desire, this need to be in the physical space I also see in my mother, who because of the pandemic has not been able to travel to her motherland the Netherlands for nearly a year now. Just like the archive-robots allow us to connect to the brick and mortar archives, my mother has been able to connect to her homeland via her devices be that FaceTime with her sister, watching dutch tv, reading dutch newspapers or listening to dutch radio. But we know it is not the same as physically being there. She wants to connect to the land. She wants to be in that physical environment. And I think this feeling is very similar to people missing brick and mortar archives as if the archive is their motherland.

I think it is necessary to understand the importance of this connection when it comes to research. Connecting with your subject of your research in an emotional way can help one be more responsible in how we handle our archival material. This is especially important in cases where the archival material is from someone who is still alive or has close living relatives, which is something that is very common with oral history. When we use our digital devices to access archival material or in fact do anything that involves interacting with humans dead or alive online we have something I am going to call “digital distance”.

Through our screens we reduce humans to a handful of pixels, a username and 240 character statements. This is digital distance and the reason why some people do or say bad things because that person to them is not fully human because the way they are presented on our screens is not fully human – you cannot look them in the eye. Now obviously you cannot look the creators of archival material in the eye because most likely they are dead. But their humanity is present in the archives in their bad handwriting, spelling mistakes and doodles. Physically being with the documents, imagining what they smelt, felt and saw when they were creating this document makes us connect on an emotional level. It reminds you that these are not just bits of isolated evidence but actually are part of a wider portrait of someone’s life. You become invested in this ghost type thing and the only way to truly feel their presence is by being in the brick and mortar archive.

This feeling of closeness that people want to have with the Mona Lisa and feeling of belonging that people have with their motherland they can be found in people desire to go back into brick and mortar archives. It is a connection that is strange and maybe nothing completely logical but very human. I think by reframing this observation as the archive as motherland highlights the importance of the physical in archiving. It is a physical activity and the fact that it is physical plays an important role in responsible researching.

How does this help me?

For my PhD I have been challenge with building an oral history archive-esque thing at the National Trust property Seaton Delaval Hall in Northumberland.

So, how can this reframing of observations into the archive-robot and the archive-motherland help me build an archive?

Reframe 1

As I said previously by reframing the frustrations of the digital archive into the naive archive-robot we put ourselves into a position where we want actively want change. We are thinking about what the archive-robot might look like when they grow up. What this reframing allows me to do is start thinking in terms of design-driven innovation. Design-driven innovation is a term used by the design scholar Roberto Verganti in a book by the same name. The idea behind design-driven innovation is seeking to change the meaning of an object or system. For example, corkscrews are there to open my wine but this corkscrew by Alessi “dances” for you and plays on you inner child. Similarly portable music players allowed you to listen to music on the move, but the iPod allowed you to cheaply buy songs from iTunes and then curate them into your own personal soundtrack.

Here we have two axis: change in technology and a change in meaning both have a scale from incremental to radical change. In the corner we have market pull/user-centered design. Here we have the bubble design-driven innovation, where see radical change in meaning and the bubble technological push where there is radical change in technology. In this yellow part where there is a radical change in meaning but not in technology we find designs like Alessi’s corkscrew. In this blue section we find technologies like the first mp3 player, which was a significant technological upgrade from portable cassette and cd players. Now in this green part we find the iPod. This green part is what Verganti refers to as a technological epiphany.

Currently our digital archives and archive-robots live here in the blue section where there is an upgrade in technology but not in meaning. As I said using the British Library does feel like they uploaded the index cards. By the way, this is not a just people being silly, human kind always does this when there is a change in technology. The first cars looked like carriages and our save button looks like a floppy disc. We don’t like radical change so we keep the meaning and symbols. But for my PhD I want to do what Apple did in 2001 and also achieve a technological epiphany. I want to upgrade the archive-robot because I think this is the perfect opportunity to do so when everyone is using digital-archives so much and complaining about them.

Reframe 2

So how will I use this idea of the archive-motherland in my work. As I briefly mention before oral history often deals with people who are still alive so looking after their archival material responsibly is imperative. That is why I do not think it is too much to ask that if you want to take information from the community you should probably think about becoming part of that community. And the only way to do that is to physically go there and look the people in the face. This is not a new idea there are many archives that only allow you to access the oral history recordings if you are in the building where they are stored. This is the case with the National Trust’s oral history archive which you can only listen to if you are in the British Library. Now I think you might be able to predict what my problem with this is. The British Library is in London and quite some miles away from Seaton Delaval Hall in Northumberland. So if I want to keep this principle of connecting to history through physical space I might have to very politely ask the British Library if they could maybe bend the rules for me.

Conclusion!

I think that what I am trying to get at here is that through these observations and reframing I think I can say that connecting with history is a deeply human process. And the way we do it and the way it is changing because of technology and the pandemic is nothing new to human kind. I think that while we do pursue these new technologies we also need to remember that emotional connection we have within the brick and mortar archives. I do not know for sure what archives will look like in a years time but a lot of it with have started now during the pandemic.

I really want to end on a quick note that I think it is really important to remember that the internet and the servers that the internet is store on use up a truly insane amount of energy and are very bad for the environment and the majority is own by amazon, which is actually a terrifying idea when you think about it.

OHD_BLG_0043 Philosophy is easier than reality

On Monday 11th April 2022 I attended and ran a workshop at the Seaton Delaval Hall Community Research Day. It was an exceptionally interesting affair and mostly certain did not go the way I imagined. If I had to sum it up I would describe it as engaging but impractical. To say that it got deep real quick would be an understatement but the to which it went was fascinating. It was also great to just bounce ideas off people. However it felt like whenever I attempt to move the conversation to getting to more practical solutions people rather stayed in philosophical and imaginary realm or they would just explain why it would not be possible to change that.

Maybe I am too much of a designer, wanting to think of solutions instead of sticking to the status quo. Or maybe this is exactly what I should be doing, building a bridge between the imaginary realm and the real world. Maybe this is the point that Verganti talks about when he discusses ‘Interpreters’. The people in that room on Monday were my interpreters, the people I can draw on for inspiration and ideas…

If this is the case it is now my job to turn the “multi-verse” of history that we kept talking about into reality. No pressure….

OHD_BLG_0047 Delete as appropriate: Bad/Good Slow/Fast

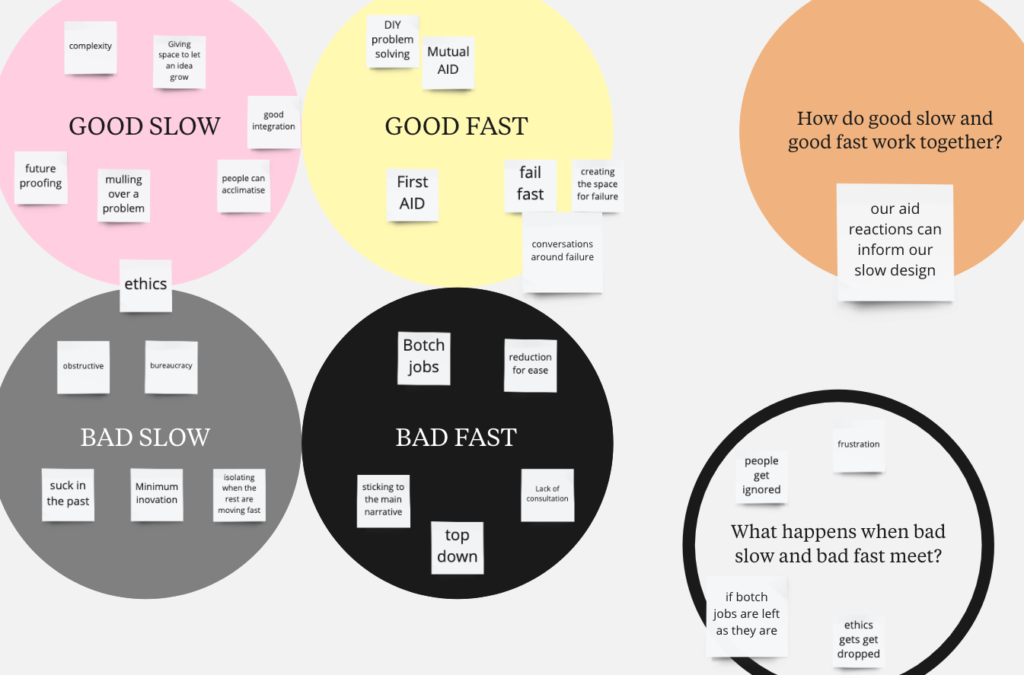

Two weeks ago I had a chat with Ollie Hemstock from Northumbria University about Slow Design. We discussed the benefits and downfalls of slow and fast design and eventually wondered what makes fast good and what makes slow good. So I took up the challenge of defining good fast and good slow, and while I was at it, I also defined bad fast and bad slow. Making myself a little online mind-map I speedily popped down virtual post-its and quickly discovered that what makes a speed good is also sometimes the reason why it is bad.

- Good Fast – Creative thinking under pressure, Google Sprint, First Aid. No overthinking. Magical solutions. Fail fast.

- Bad Fast – Drawing on stereotypes and single narratives. Reducing information, and a lack of consulting. Can do damage.

- Good Slow – Allowing ideas to grow. Future proofing. More room for nuance and complexity. Ethics.

- Bad Slow – Obstructive bureaucracy. Sticking to the past. Minimal change.

Fast does not give you enough time think, which makes things less complicated but also reduces information and abandons nuance. Slow makes loads of room for nuance but can block change in fear mistakes. One is therefore not better than the other. But what happens when we combine the two.

Good Fast + Bad Slow

Good Fast is blocked by Bad Slow killing innovation. Good Fast means testing and failing fast but Bad Slow would put a stop any testing.

Bad Fast + Good Slow

While Good Fast is blocked by Bad Slow, Bad Fast and Good Slow stand in complete opposition. They simply cannot happen at the same time. Bad Fast is bad because there is little thinking, while with Good Slow there is loads of thinking. These two cancel each other out.

Bad Fast + Bad Slow

In this combination someone quickly solves a problem but then does not go back to reflect on it. For example someone does some botch DIY which works at first but really needs a long term solution, however bureaucracy and rules are blocking that long term solution from happening.

Good Fast + Good Slow

Instead of being blocked by Bad Slow, Good Fast releases information that is then integrated into Good Slow’s thinking process. Here there is an agreement between the two speeds that failure is good for the future but that you need to be able to put the breaks on at any moment. It is the ultimate feedback loop. Like a well run household, because sometimes you need a quick book under a table leg and other times you need to slowly work out where you actually what to put a shelf.

OHD_BLG_0048 The right to repair 🛠

The right to repair is important and connected to my work because like many things in the world it has to do with maintenance. I had a chat with O Hemstock from Northumbria University about slow design and he brought up that maintenance is about agency. It is about the right to repair and the power you have over the objects that make up your life. Having agency means that you can fix it when it is broken, you don’t need to rely on others to fix it for you and you are not forced to buy another. But it is also about the ability to customised and edit and make the object fit to your needs instead of the other way round. It is important to think about maintenance not only because of the planet but because of the effect objects have on people’s lives. For example you want a pan to be good but what if the person burns something in the pan, which they are likely to do because they are human. What do you as the producer of the pan do then? Sure technically the ownership of the pan has moved from one to another but what can you do to help the new owner with maintenance of the pan. Handy youtube videos on how to clean your pan or a cleaning service for example. Now I am aware that the pan scenerio is a bit of an odd one but thinking about maintenance is always a good thought exercise in design.

OHD_PRT_0016 Failed Archive – again (formerly a blog post)

Let me start at the beginning…

I wanted to do an inventory of my work so far – see my journey. To do this I went through my blog posts, bits of longer writing, mind maps, and all the bits and bobs on my website. I noted them all down on a post it and sorted them into five categories: the big idea/overall concept, development of stuff, development of space, historical maintenance, and background maintenance. Super proud of myself, I thought that I finally had the basic idea for my PhD by practice; an archive in various different forms (digital and analogue) with some lovely categories that people can look through.

Two weeks later I go through my “archive” because I need to write a summary of my first year. I start going through my post its and concluded that everything is in the wrong place…

*sigh*

CATEGORIES NEVER WORK! People always change their mind or are looking for something different. Tagging is therefore the only option. They are flexible and very easy to word search.

( how to make it analogue is not easy but is an interesting thought experiment )

💡💡💡💡💡💡💡💡💡💡💡💡💡💡💡💡💡💡

Here is an idea…

Instead of having an archive where there is detailed cataloguing done by one archivist, all we do is give items a code, a date of entrance into archive, and a brief description of archive item. No need to catalogue in a specific spot.

Then all people need to do is word search the archive and whenever people bring up an item, they are invited to add their own description, increasing the word search capabilities.

Like URBAN DICTIONARY

OHD_BLG_0049 Testing archives

I have realised a rather large problem with my project and that is that it is very difficult for me to test out my ideas. I am essentially building an archive-like system and the true test of an archive is to see how well it stands up to time. Within the time frame of my CDA I will not be able to truly see how well my archive system works both from a user point of view and the maintenance workers.

I wonder if there is any literature on this that could help me workout how to test long term products in the short term…

OHD_BLG_0060 Creative Tensions

From conflict to catalyst: using critical conflict as a creative device in design-led innovation practice

by Nathan Alexander STERLING, Mark BAILEY, Nick SPENCER, Kate LAMPITT ADEY, Emmanouil CHATZAKIS, Joshua HORNBY

I read this on Mark’s recommendation because I was talking about the workshops I wanted to run and how I wanted to set them up in a way that allow there to be tensions that can then be explore creatively. So reading this paper was probably a sensible thing to do.

Diversity?

The piece features a project that brought together a “diverse” group of people to think of ways to solve the wicked problem of cyber-crime under teenagers. The “diversity” of the group is not expanded on beyond that it was several people who either were doing or had done the MDI masters, police officers, and a couple of members of the public. This does not really explain the diversity to me. I want know where these people came from, how digitally literate are they, what ages are they? None of this information is enclosed which makes it hard for me to fully imagine the diversity. For all I know the diversity lies in the participants different heights.

We need to show this information because then I can truly see the diversity rather then relying on people word, which is really hard since the idea of diversity is subjective and it is a word that is very much thrown about.

Get out of my shoes

The paper talks a lot about “deep empathy” which when I first learnt about it during my masters I was on board with, now I very much reject this idea. Why the sudden change of heart? Well, for me it started to become clear that terms like “deep empathy” is a gimmicky way to show the performance of diversity. Instead of actually employing a diverse group of people we bring diversity in for a workshop, get them to do a couple of exercises and then send them on their merry way. The paper does note that some participants thought that you could not really get a in depth and nuanced idea of someone’s point of view because of the time limit and the group setting.

I personally think that telling ourselves that we can fully understand where people are coming from in a short space of time is delusional and reductive. If I am being completely honest I do not think I will ever be able to understand the experience of a black man. A white man? Maybe. But only because of the cultural domination of white men. But a black man? No way. A person in a wheelchair? Nope. A transgender person? No. It is not because I do not try, but because I believe that one cannot communicate a human life through words alone.

“Deep empathy”, “active listening” etc. these can all work in an attempt to understand people, but we should not deluded ourselves that we can embody another person’s life experience. I think it’s really necessary to put an intersectional feminist lens over this, because it is a dangerous path to go down.

The DaDa way

Now here is something fun. The participants thought that by blowing up the creative tensions and making them very obvious people could better understand them and use them. They also wanted the view points to be a bit more than a line of text (news flash you cannot judge someone by their tweet). People wanted images, videos, animations. These were things they felt they could relate to better. This got me thinking about a discussion I had with Joe about a podcast, the Bodega Boys. The podcast is super strange to listen to but because everything is very absurd they can tackle difficult issue. In this podcast they create this strange but safe space. The absurdity makes the issues more approachable and digestible. This then got me thinking about DaDa and how they came to be in a time of a nonsensical war. We are kind of in a nonsensical time now, maybe we need Dada to create empathy.

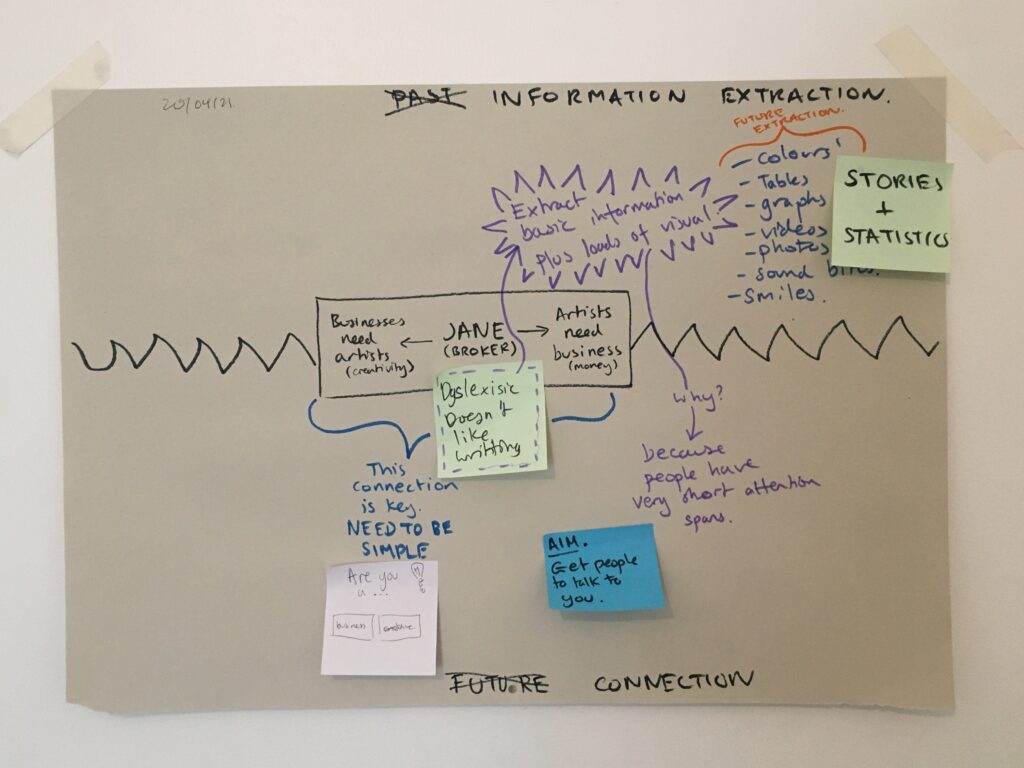

OHD_BLG_0062 Create a bit

Summary of the Createathon 19/04/21 – 23/04/21

I took part in a Createathon because it has been a while since I had done a design workshop and I wondered if I could still do it.

During the first day of the workshop I started to remember some of the painful aspect of doing design workshops. For example the time limit, in my opinion, dulls the creative process a bit, so you start thinking of easy wins instead of bigger pictures. There is was also a lot of rambling talking which was a little frustrating.

However…

In the end my group, which was a girl from Azerbaijan and a PhD student who had also work with Seaton Delaval Hall, delivered a pretty good presentation and we didn’t mention social media once! We had not really come up with super great ideas, instead we had kept it pretty open ended and offered the person whose business we were working with only a vague direction for the future. I personally thought that it wasn’t going to go down well but it really did. After we had explained the plans of actions and presented our Pecha Kucha, the client was super enthusiastic, because she suddenly saw her business in a different light. We told her her story but how we understood it and this process of multiple translations help her get an inspirational boost.

What I took away from the Createathon is that what I really want to do as a designer is not give someone a stack of clear cut ideas but a new way of thinking. I want this because that is far more sustainable in the long run and it is also harder to dismiss. You can throw away a stack of ideas but if I have incepted a new way of seeing the world into your brain that is hard to ignore.

OHD_BLG_0087 Design Thinking Sprint report – 03/02/21

I did a mini design sprint today. It was really fun to do something design-y after such a long time. It was about data and data collection. At the beginning the workshop lead showed us different data collection tools, including ‘My Activity’ page on my Google account. On this page I could see what they had been tracking but I also saw how I could turn them off or at least ‘pause’ them. This makes me think that they can unpause them at some point like how your bluetooth automatically switches on all the time.

During this mini design sprint we were challenged to design the app for Newcastle University, which is something I had already done for the university across the road during MDI. The end product my team came up with was a personalised data set report.