Tag Archives: Ethics

OHD_SSH_0147 Important dead link

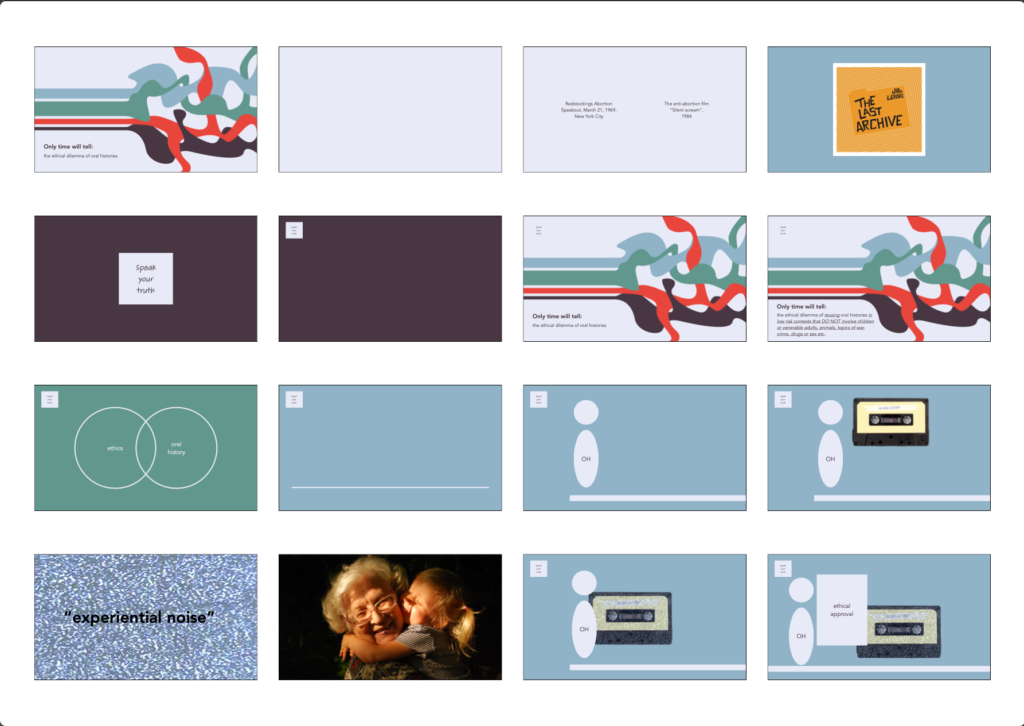

OHD_PRS_0127 Only Time Will Tell: the ethical dilemma of oral histories

This one has been my favourite paper to present so far. I think it was really fun and people seemed to enjoy it.

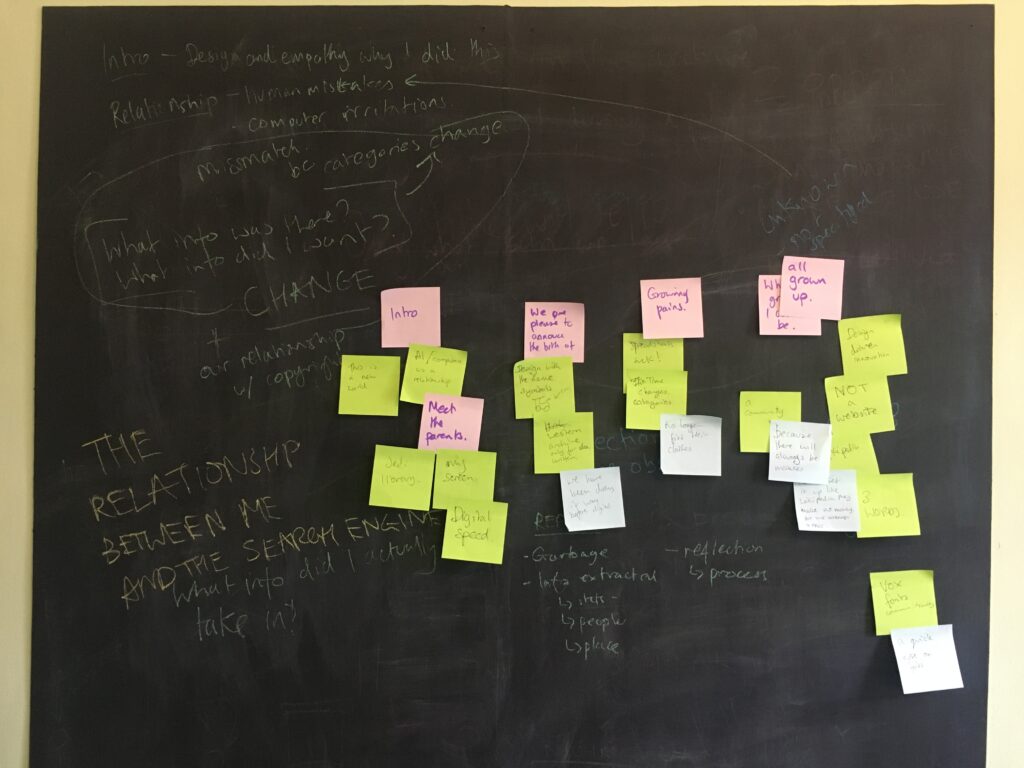

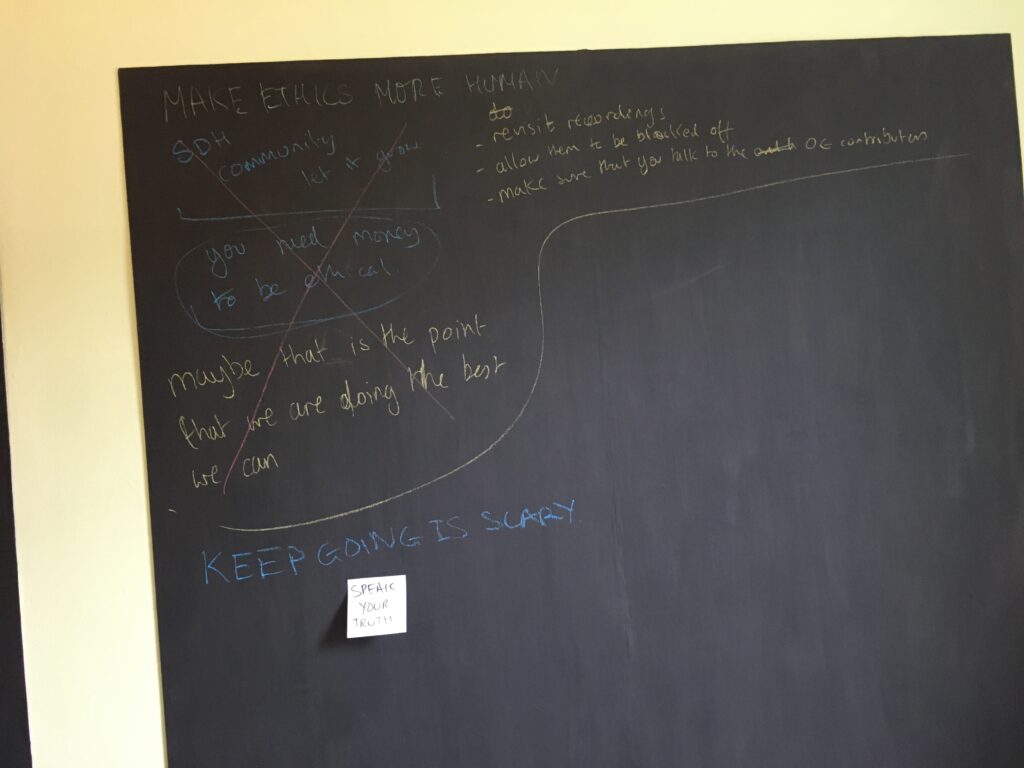

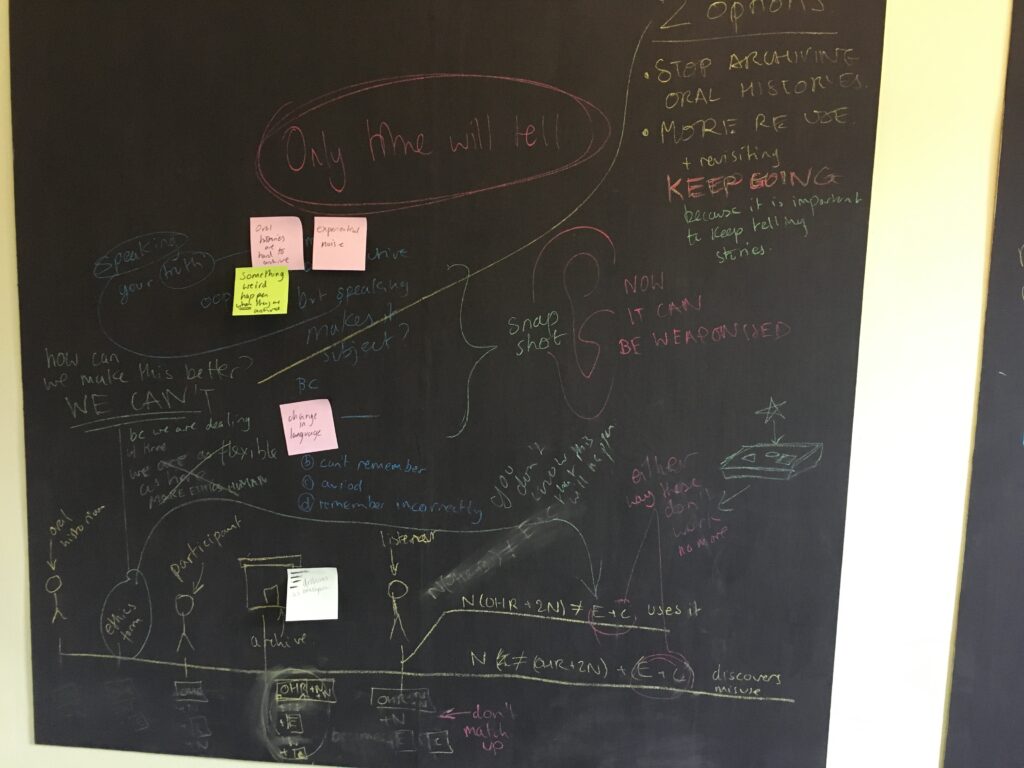

Brainstorming

Slides

Script

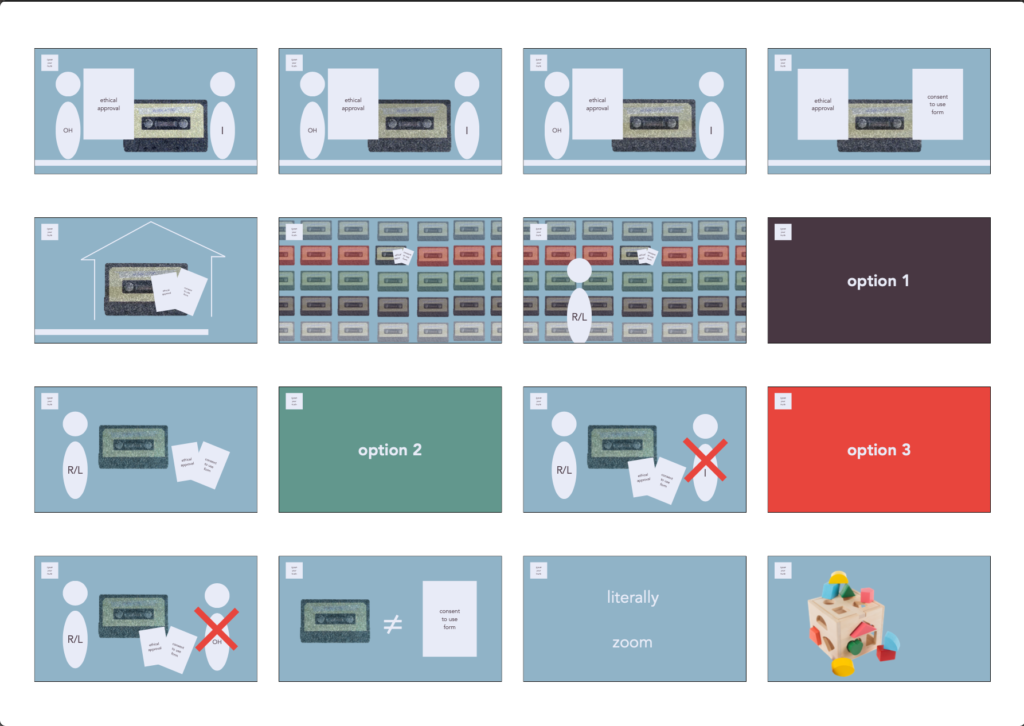

[slide 1]

I am going play two sound recordings which both discuss abortion, so if you think this might upset you I invite you to mute your computer and after I have played them I will signal in the chat that you can unmute.

(Plays segment from Redstockings Abortion Speakout, March 21, 1969, New York City and the anti-abortion film “Silent scream”)

[slide 2]

The first clip we listened to was from the Redstockings Abortion Speakout, which took place on the 21st March 1969 in New York City. The second clip was from the anti-abortion film “Silent scream” made in 1984.

[slide 3]

Both are featured an episode of the podcast “the Last Archive” made by historian Jill Lepore. In this podcast Lepore is trying to work out who killed truth and in this specific episode she discusses how the concept of “speaking your truth” that was used at the Redstockings’s Speakout contributed to creating the post-truth era we live in now. The whole podcast, but especially this episode haunted me whenever I started writing this paper. I would try to add it in but it did not really work, so in the end I extracted this haunting from my brain by writing

[slide 4]

“speak your truth” on a post-it and popping it in the corner of my blackboard. I am going to do a similar thing now and

[slide 5]

just leave a digital post-it in the corner of my presentation.

[slide 6]

I realised that the title of my presentation is a rather ambitious, so I would like to make some amendments to in order to better frame what I am going to talk about.

[slide 7]

(Only Time Will Tell: the ethical dilemma of reusing oral histories in low risk contexts that DO NOT involve children or venerable adults, animals, topics of war, crime, drugs or sex etc.)

I am specifically looking at how to encourage reusing oral histories and the case study I am basing my research on is the National Trust property Seaton Delaval Hall in Northumberland, which I assume will produce relatively low-risk oral histories.

[slide 8]

In this presentation I am going to map out the basic relationship between ethics and oral history that I imagine I will experience during these next three years.

[slide 9]

Here we see a timeline of the life of an oral history.

[slide 10]

At the start we have our oral historian, who wishes to conduct an oral history project.

[slide 11]

This is the beginning of the oral history’s life. Already from the start this oral history is affected by something I am going to call

[slide 12]

“experiential noise”. I am using this term to refer to how a person perceives the world at that moment in time, which is influenced by everything from what is in the news to whether they were hugged enough as a child. I specially use the word noise because I find it to be a very nebulous and volatile feeling. Here is a quick example of experiential noise in action.

[slide 13]

This is a picture of someone hugging their grandparent: before the pandemic this would have be a lovely picture of intergenerational love, however now you hope that the grandparent has had both their jabs.

[slide 14]

The oral historian’s experiential noise affects the oral history straight away. Lynn Abrams, refers to this as her “research frame” and discusses in the Transformation of Oral History how her position as a “university lecturer in women’s and gender history” influenced her interviewees testimonies when she did a project on women’s life experiences during the 1950s and 1960s.

[slide 15]

The next step in the life of the oral history is to get ethical approval. How to gain this differs between institutions. I have completed my first ethical approval for my low-risk project and it was relatively painless. I consider myself lucky.

[slide 16]

Clutching its ethical approval the oral history moves on to meet the interviewee, who has plenty of experiential noise.

[slide 17]

The interviewee’s experiential noise is very complicated because they are the ones who are remembering. Memory is messy and potentially all sorts of confabulation, misremembering and gaps can appear during the process.

Now we have all this noise that is being supplied by the interviewer and interviewee, but as soon as the record button is pressed all of it is frozen.

[slide 18]

Stopped. Now we move onto a really important step for my project. The recording can now be archived, which means that it can then be reused and reusing is the thing I am focusing on.

[slide 19]

But we must not forget to consult the consent form, that is the appropriate permissions and clearances, which if I am being honest have no idea of:

- I haven’t done it yet

- It’s different for everyone

- GDPR is confusing

[slide 20]

But let us say for the sake of the story that it has been stored and is available.

[slide 21]

Our little oral history can happily nestle between all the others holding its consent form and ethical approval close to its heart.

[slide 22]

Some time has passed and along comes a researcher/listener. Being a pestilent human means they are full of new fresh experiential noise. Once they and the experiential noise come in contact with the oral history three things can happen:

[slide 23]

Option one:

[slide 24]

The listener listens to the oral history, goes on to write an account of why things changed or stayed the same with a full understanding of the context in which the oral history was created and the experiential noise that was present.

[slide 25]

Option two:

[slide 26]

Because of their experiential noise the listener listens back to the oral history and is shocked by what they hear and goes on to write something about the interviewee that is not flattering. Joanna Bornat recalls a situation where the testimonies of white Australian housewives, who initially had been interviewed about domesticity, were used to illustrate racism in 20th Century. Having their oral histories used in this way was not something the interviewees had agreed to when they gave permission for their oral history to be archived. It also suggests, as did the housewives, that racism has a history. They believed and said things then that they would not believe and say now.

[slide 27]

Option three:

[slide 28]

Again because of their experiential noise the listener listens back to the oral history and is shocked by what they hear because they are surprised that this is allowed to be public. Our relationship with privacy has changed a lot over the last few decades, as has the relationship between researcher and researched. An example of this could be when the historians Peter Jackson, Graham Smith and Sarah Olive, reused the testimonies found in the archive, the Edwardians. Theyfound that the interviewers had included field notes on the interviewees that contained information that definitely would not pass an ethics review or board these days.

[slide 29]

In both option two and three the ethical approval and the consent to use form no longer matched up with the oral history, because the reception of the oral history had changed. The words said have not changed but their meaning has. The passage of time has not just changed the experiential noise of the listener/researcher but the whole of society’s. This is not surprising as language changes all the time, just think of the word

[slide 30]

literally or zoom.

This is why oral histories are so difficult to archive and write ethics for.

[slide 31]

The best way I can describe it is like one of those toys where you have to put right shape through the right hole.

[slide 32]

Only in the case of oral histories the shape keeps changing.

So what do we do now?

Well I offer three options:

[slide 33]

Option one:

[slide 34]

Stop recording oral histories, stop archiving them, stop asking money for them. It’s just going to be an ethical mess. Stop it.

Now I am going to go on a whim here and assume this probably is not what people are looking for.

[slide 35]

Option two:

[slide 36]

We can try and improve our ethics forms to accommodate its noisy nature. Maybe if we make a system that forces us to annually update our ethics and consent forms we can keep up with the noise. Now considering how much time and effort already goes into ethics I imagine that this option is also not realistic. It reminds me of Wendy Rickard writing in her paper Oral history – ‘more dangerous than therapy’ that she wishes that more interviewees and interviewers could listen back to their tapes, but that this is simple not possible due to lack of resources – “it seems you have to be rich to be ethical”.

[slide 37]

Option three:

[slide 38]

To start with we do more reusing. According to Michael Frisch within oral history there is a preference to record interviews instead of reuse them. This results in less information on the process of reusing. Which is why I am suggesting that we reuse more so we can learn more about it. The more we revisit, the more we can reflect, the faster we can pick up on ethical misdemeanours or challenges and the more we can improve the process of recording, archiving and reusing oral histories. We need to become more practiced in reusing and learn more about the ethical pitfalls of reuse. It is important to keep telling these histories that people have worked hard for to capture, but this also means we need to keep the shop tidy. Sometimes we might make a mistake but then it is our responsibility as a community to fix it and grow.

[slide 39]

We are never going to be able to write the perfect ethics form. Time affects how we experience oral history so we need to find something that is as stubborn and relentless as time which I believe is

[slide 40]

us (the human race)—the vessels of experiential noise and the deciders of

[slide 41]

“what is ethical?”.

[slide 42]

Like our history, our ethics change with us because it lives within us, so trying to shove all the nebulous responsibility onto a single static document does not make sense. So for now we might just have to hustle though because only time will tell if we are doing it right.

[slide 43]

But there is one more thing…

[slide 44]

The post-it note. “Speak your truth”.

So after I had finished planing this paper, I stared at the post-it note for while contemplating its existence. Eventually I concluded that the option three, where we embrace reusing and all its messiness was really scary. In this post-truth world where everyone “speaks their truth” and does not listen to each other it is terrifying to simple get on with and keep going. As an oral historian you could ruin someone’s life because you allowed public access to their testimony and someone completely misused it. You could write something and be “cancelled” or “trolled” for your opinions. Or you can have your funding cut by your government because the narrative your telling is not what they want to hear.

[slide 45]

Initially I was going to end it here in a slightly depressing way, but I sent my draft to my supervisor who said that I might be over-worrying a little bit. His words reminded me of something my old neighbour used to say, something that I think is important when you do pretty much anything in live including research:

[slide 46]

“all perfect must go to Allah so if you want to keep your rug you have to make a little mistake”

OHD_LST_0123 questions

Here is a collection of questions I have asked myself concerning the topic of my PhD both big and small.

How do we handle the racism that exists in the archives? Date: 16/06/2020

What do we do with unused interviews? Date: 19/06/2020

Do we need to reevaluate how we create oral historians in order to ensure more equality within the sector? Date: 16/06/2020

What is the difference between a documentary and an oral history project or article? Are they not both curated equally? Is the only true form of oral history stuck unedited in the archives? Date: 20/07/2020

How can we utilise Gen z and the digital natives in oral history archives? What might the pitfalls be? Date: 21/07/2020

Do I have a problem with the word history in the context of oral history interviews? Date: 21/07/2020

Are there any aural oral history papers? If so where are they and why aren’t there more of them Date: 01/10/2020

How does the archive function in a ‘knowledge/data’ economy? Date: 23/10/2020

Do filters for the public limit or increase accessibility? Date: 23/10/2020

Are we looking for an ‘archive’ or a completely new system? Date: 23/10/2020

What should an archive be like during an pandemic? Date: 08/02/2021

How does “Material History” work in the context of oral history? Date: 08/02/2020

Do we get bogged down in the ethics? Date: 16/02/2021

What is our relationship to the ‘public’? Date: 16/02/2021

What does digitization replace? Date: 10/03/2021

Are result lists the problem when it comes to searching? Date: 12/02/2020

What does it mean if people can’t remember? When people are scared of not being able to remember? Date: 16/03/2021

Where does intertextuality and oral history theory end and academic snobbism begin? Date: 16/03/2021

Is having an oral history recorded like donating your body to science? Date: 16/03/2021

What do the interviewees think about reuse? Date: 16/03/2021

How do we take stuff back to the interviewee? Date: 16/03/2021

How do you build a community? Can you build a community? Or do they only grow naturally? What is the balance between setting up/designing a community and having one naturally occur? Date: 30/04/2021

Can the digital ever be transparent if those who make it are from one exclusive group? Date: 11/05/2021

Do we trust archives? Date: 11/05/2021

Does our idea of original need to change? Date: 11/05/2021

Can you democratise history outside of a democracy? Date: 07/05/2021

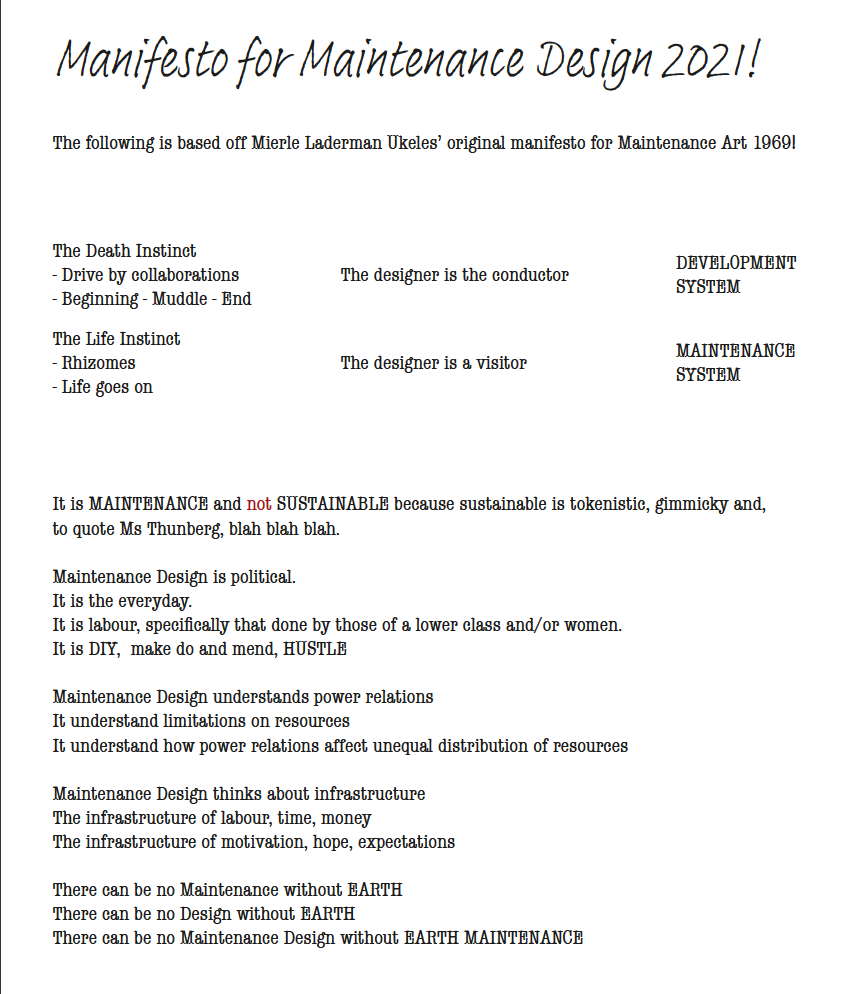

OHD_WRT_0121 the code/manifesto

The manifesto below is based off Meirle Laderman Ukeles’ Manifesto for Maintenance Art.

This the code of ethics outlined in by Mike Monterio in Ruined by Design. I am using this as a base for my code of ethics for this project. I have written a summary of each rule and then written in the green text how I might fulfil it.

A designer is first and foremost a human being.

Designers work within the social contract of life. Within their work they need to respect the globe and respect fellow humans. If their work relies on the inequalities in society they are failing as a human and a designer.

This project risks becoming a completely digital affair, which can be alienating to some in society, especially the elderly who make up the majority of this project’s audience. Another large responsibility is making this an eco friendly venture, which in my opinion is essential but not easy.

A designer is responsible for the work they put into the world.

The things designers make, impact people’s lives and have the potential to change society. If a designer creates in ignorance and does not fully consider the impact of their work, whatever damaged then is caused by their work is their responsibility. A designer’s work is their legacy and it will out live them.

This is where I think an oral history project about this project will encourage an awareness around the impact of the design. If one of the first things the archive designed houses is recordings of those would built it, it will show confidence in the work. The legacy of the project will live within the outcome of the project.

A designer values impact over form.

Design is not art. Art lives on fringes of society, design lives bang in the middle of the system of society. It does NOT live in a vacuum. Anything designed lives within this system and will impact it. No matter how pretty it is if it is designed to harm it is designed badly.

Nothing a totalitarian regime designs is well-designed because it has been designed by a totalitarian regime.

M. Monterio ‘The Ethics of Design’ in Ruined by Design

Let’s make it inclusive before we pick out the font. This is especially a rule for me, a former artists.

A designer owes the people who hire them not just their labor, but their counsel.

Designers are experts of their field. Designers do not just make things for customers, they also advise their customers. If the customer wants to create something that will damage the world it is the designer’s job as gatekeeper to stop them. Saying no is a design skill.

The team at the National Trust and the oral history department are (relatively) new to the world of design so it is my job to help them navigate this rather messy world.

A designer welcomes criticism.

Criticism is great. Designers should ask for criticism throughout the design process not only to improve the thing being designed but the designer’s future design process.

Now that I am working between three different parties it is essential that I keep communication open at all ends. The more the merrier attitude must reign.

A designer strives to know their audience.

A designer is a single person with a single life experience, so unless they are designing something solely for themselves they probably cannot fully comprehend complexity of the problems their audience is facing. Therefore it is designers’ responsibility to create a diverse design team, which the audience plays a big role in.

This collaborative project is perfectly set up the fulfil this, as long as COVID-19 does not get in the way.

A designer does not believe in edge cases.

‘Edge cases’ refers to people who the design is NOT target at and therefore cannot use. Designers need to make their design inclusive. Don’t be a dick.

The National Trust has a very particular audience which in some design projects would make them edge cases. In this project I think I need to look at how people with disabilities would use the archive and people who are not native to digital technology.

A designer is part of a professional community.

Each individual designer is an ambassador for the field. If one designer does a bad job then the client will trust the next designer they hire less. It also goes the same way, if a designer refuses to do a job on ethical grounds and then another designer comes along and happily completes the job, then the field becomes divide.

This collaboration between Northumbria University, Newcastle University and the National Trust has the potential to be the start of a series of collaborative projects. It is therefore my responsibility to ensure a positive working relationship with all involved. I need to be aware that I am an ambassador for all the institutions involved.

A designer welcomes a diverse and competitive field.

A designer needs to keep their ego in check and constantly make space for marginalised groups at the table. A designer needs to know when to shut up and listen.

I want to invite everyone to the party. Because the collaboration I have access to all the experts at the university but also at the National Trust. And each institution also has a huge and diverse group of people who can help influence and criticise the work. Think MDI and the volunteers at Seaton Delaval Hall.

A designer takes time for self-reflection.

Throwing away your ethics does not happen in one go, it happens slowly. Therefore constant self-reflection is essential. It needs to be built into each designer’s process.

I started doing this during MDI so now I can build on it. Maybe this website can help me reflect by holding all my thoughts. I should probably also timetable in moments of reflection from the off.

OHD_BLG_0046 the nerd filter

The nerd filter is an idea that I have been mulling over for a while now. The basic principle is that you gain more access to an archive the more time you spend in the archive and interacting with the archivists. In other words as you get more integrated into the community of the archive you are able to view more sensitive documents. I see it as a type of social trade. The user invest their time into the archive and exposes themselves to the eyes of the archivist and in return they gain trust and access to other documents. The reason it is called the nerd filter is because those who are not as passionate or “nerdy” will eventually give up and leave the archive community. The people who are then left behind are the proper nerds, who have a significant amount of social capital with the archive. My theory is that these leftover nerds will be more responsible with archive material because they risk losing the access they worked so hard for if they betray the archive community.

It is like a type of loyalty card scheme, but whether it will be taken on by archives is another question…

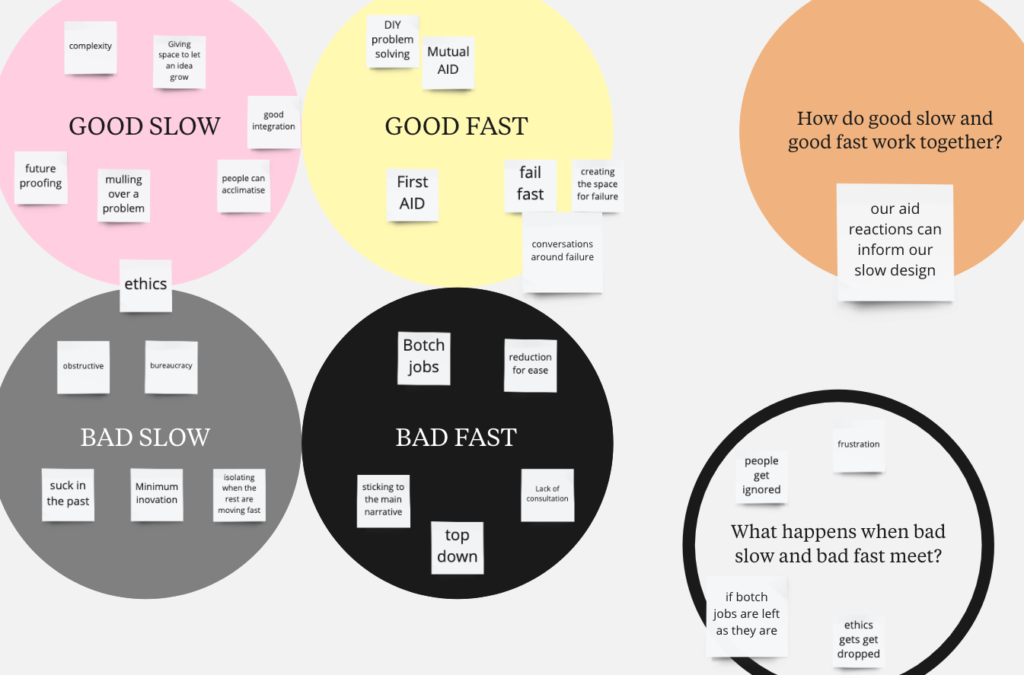

OHD_BLG_0047 Delete as appropriate: Bad/Good Slow/Fast

Two weeks ago I had a chat with Ollie Hemstock from Northumbria University about Slow Design. We discussed the benefits and downfalls of slow and fast design and eventually wondered what makes fast good and what makes slow good. So I took up the challenge of defining good fast and good slow, and while I was at it, I also defined bad fast and bad slow. Making myself a little online mind-map I speedily popped down virtual post-its and quickly discovered that what makes a speed good is also sometimes the reason why it is bad.

- Good Fast – Creative thinking under pressure, Google Sprint, First Aid. No overthinking. Magical solutions. Fail fast.

- Bad Fast – Drawing on stereotypes and single narratives. Reducing information, and a lack of consulting. Can do damage.

- Good Slow – Allowing ideas to grow. Future proofing. More room for nuance and complexity. Ethics.

- Bad Slow – Obstructive bureaucracy. Sticking to the past. Minimal change.

Fast does not give you enough time think, which makes things less complicated but also reduces information and abandons nuance. Slow makes loads of room for nuance but can block change in fear mistakes. One is therefore not better than the other. But what happens when we combine the two.

Good Fast + Bad Slow

Good Fast is blocked by Bad Slow killing innovation. Good Fast means testing and failing fast but Bad Slow would put a stop any testing.

Bad Fast + Good Slow

While Good Fast is blocked by Bad Slow, Bad Fast and Good Slow stand in complete opposition. They simply cannot happen at the same time. Bad Fast is bad because there is little thinking, while with Good Slow there is loads of thinking. These two cancel each other out.

Bad Fast + Bad Slow

In this combination someone quickly solves a problem but then does not go back to reflect on it. For example someone does some botch DIY which works at first but really needs a long term solution, however bureaucracy and rules are blocking that long term solution from happening.

Good Fast + Good Slow

Instead of being blocked by Bad Slow, Good Fast releases information that is then integrated into Good Slow’s thinking process. Here there is an agreement between the two speeds that failure is good for the future but that you need to be able to put the breaks on at any moment. It is the ultimate feedback loop. Like a well run household, because sometimes you need a quick book under a table leg and other times you need to slowly work out where you actually what to put a shelf.

OHD_BLG_0060 Creative Tensions

From conflict to catalyst: using critical conflict as a creative device in design-led innovation practice

by Nathan Alexander STERLING, Mark BAILEY, Nick SPENCER, Kate LAMPITT ADEY, Emmanouil CHATZAKIS, Joshua HORNBY

I read this on Mark’s recommendation because I was talking about the workshops I wanted to run and how I wanted to set them up in a way that allow there to be tensions that can then be explore creatively. So reading this paper was probably a sensible thing to do.

Diversity?

The piece features a project that brought together a “diverse” group of people to think of ways to solve the wicked problem of cyber-crime under teenagers. The “diversity” of the group is not expanded on beyond that it was several people who either were doing or had done the MDI masters, police officers, and a couple of members of the public. This does not really explain the diversity to me. I want know where these people came from, how digitally literate are they, what ages are they? None of this information is enclosed which makes it hard for me to fully imagine the diversity. For all I know the diversity lies in the participants different heights.

We need to show this information because then I can truly see the diversity rather then relying on people word, which is really hard since the idea of diversity is subjective and it is a word that is very much thrown about.

Get out of my shoes

The paper talks a lot about “deep empathy” which when I first learnt about it during my masters I was on board with, now I very much reject this idea. Why the sudden change of heart? Well, for me it started to become clear that terms like “deep empathy” is a gimmicky way to show the performance of diversity. Instead of actually employing a diverse group of people we bring diversity in for a workshop, get them to do a couple of exercises and then send them on their merry way. The paper does note that some participants thought that you could not really get a in depth and nuanced idea of someone’s point of view because of the time limit and the group setting.

I personally think that telling ourselves that we can fully understand where people are coming from in a short space of time is delusional and reductive. If I am being completely honest I do not think I will ever be able to understand the experience of a black man. A white man? Maybe. But only because of the cultural domination of white men. But a black man? No way. A person in a wheelchair? Nope. A transgender person? No. It is not because I do not try, but because I believe that one cannot communicate a human life through words alone.

“Deep empathy”, “active listening” etc. these can all work in an attempt to understand people, but we should not deluded ourselves that we can embody another person’s life experience. I think it’s really necessary to put an intersectional feminist lens over this, because it is a dangerous path to go down.

The DaDa way

Now here is something fun. The participants thought that by blowing up the creative tensions and making them very obvious people could better understand them and use them. They also wanted the view points to be a bit more than a line of text (news flash you cannot judge someone by their tweet). People wanted images, videos, animations. These were things they felt they could relate to better. This got me thinking about a discussion I had with Joe about a podcast, the Bodega Boys. The podcast is super strange to listen to but because everything is very absurd they can tackle difficult issue. In this podcast they create this strange but safe space. The absurdity makes the issues more approachable and digestible. This then got me thinking about DaDa and how they came to be in a time of a nonsensical war. We are kind of in a nonsensical time now, maybe we need Dada to create empathy.

OHD_BLG_0065 New words among other things

Readings:

Community archives and the health of the internet by Andrew Prescott

Steering Clear of the Rocks: A Look at the Current State of Oral History Ethics in the Digital Age by Mary Larson

Sometimes I feel like we are in the trenches with our machine guns and old military tactics…

This ain’t for you

People live their lives in very specific ways. They have certain rituals and values that they hold very close to their hearts. However it is very unlikely that everyone else in the world has the same approach to life as you do. Some people do not use the right tea towel in my opinion, some people think it is perfectly fine to wear socks in sandals, and some people a zero problems with eating meat everyday. In the case of Prescott’s paper on community archives/Facebook groups we have an academic freaking out because a community is not archiving properly something which he considers to be a great sin, and yes, in a certain way it is a great shame that a community archive is not sustainable because of the platform used or the limited funding. This is especially the case when you come from an oral history angle where one really wants to preserve the voices of those who current fall outside of history. However, maybe we need to remove the academic lens in these situations, maybe these archives just aren’t for you. They have a different, more temporary, function to bring people together over a shared history. They are about sharing history not preserving history like archives do.

This is where I think I (as an academic 🤢) feel that my role is not to impose my beliefs onto these make-do archives but instead build better tools to support them. A community archive on Facebook is a different beast to the university backed oral history project. Truly it is a shame that this knowledge might go missing, but then I suggest that we get more minorities to work in academia rather than dictate what we think they should do.

It’s a power thing.

Anonymity is anti-oral history ?

…, anonymity is antithetical to the goals of oral history if there are no exacerbating risk factors.

Mary Larson

Anonymity, accountability, freedom of speech, privacy, welcome to the 21st century. There is the opinion within the field of oral history that anonymity is against the principles of oral history. This is mostly because oral history demands a high level of context in its reuse, which makes complete sense. However does that mean that all information should be available? Is it impossible to have different levels of anonymity?

It seems odd that currently when it comes to privacy we have to work in such absolutes. You can get a certain level of privacy on the internet but that often requires lots of digging around and downloading plugins that send out white noise. You basically have to spend time fending off those who run the platforms you use, which when put in a AFK context would be the equivalent of the shop keeper pickpocketing you while you were shopping. Currently privacy and anonymity equals not using either the internet or archives, which defeats the point.

Why is this our only option?

Well, in my opinion it is not. We just need to get a bit more creative for example:

- Use pseudonyms

- Use other identifiers e.g. White, young adult, middle class, female (that’s me)

- Use identifiers + 𝓲𝓶𝓪𝓰𝓲𝓷𝓪𝓽𝓲𝓸𝓷. There are loads of researchers who have to use their imagination because history has not been good at recording their subject

- Only allow access to certain information if you either visit the BAM archive or ask for permission

- Generally encourage more thorough and ethical reuse and research

New words

To elaborate on that last point we currently approach the ethics around archiving from the donating angle; if everything is correctly archived now there will definitely be no more problems in the future. This attitude I do not find very sustainable because attitudes towards ethics change all the time. So instead I purpose a different angle: ethical reuse of archival material lies predominantly with the reuser not the donator. This is where I would also like to insert the ‘new’ words. Instead of using the terms ethical and ethics we instead use responsibility and care, because the former is so slippery so ‘high-level’ thinking that it loses its meaning while the latter are more human words. Responsibility and care are concepts that you teach your children. They are more instinctive. So what I wish for is more care and responsibility from those who reuse oral histories. I want the reuser to remember the human-ness of the archive and the responsibility they have to care for their other humans.

NOTE: this is why I love the idea of archival ghosts so much because it gives the oral histories a face.

OHD_BLG_0070 Reading Group – 16/03/21

Readings

Families remembering food: revising secondary data by Peter Jackson et al.

Secondary analysis reflection: some experiences of re-use from an oral history perspective by Joanna Bornat

Dynamic Attitudes

Everyone views the world through their own personal lens and academics are not exempt. If when an academic sets out on their researching journey they already have a vague idea about what they are going to write about. An oral historian will pick people to interview based on this idea and will ask questions that will fulfil this idea. However, many unexpected things can happen during research that causes you to change your attitude, readjust your lens etc. Your mindset evolves with the project and there is nothing you can do to stop it. This is why constant reflection is so important because our thought process is never static.

Reuse is not the issue, its about permissions

To reuse an oral history can be very valuable but because everyone views history through a different lens it is likely that the reuser will have different attitude to the creator. This results in different conclusion to be made from the same source. However, oral histories are set up in a way that makes the source only give permission for the creator’s interpretation and not necessarily the reuser’s. This is why it’s not about the reuse of oral histories, we know that creates value, but the permissions around the new interpretation, the one that was not necessarily agreed on by the source.

Even if the source agreed that their recording is open source the reuser might still feel the need to ask for permission especially if that person is still alive.

Recording for reuse

What this reading group made clear to me was that the particular oral histories I will be recording are solely for reuse. I am not planning on writing any analysis on the content of the recordings I just need to make sure that they can be reused properly. Reuse is my mission. I have no lens to work through. (Only the subconscious ones and the large one where I am super focused on getting ALL information.)

Always reflect

This reflection is not only for the interviewer but also for the interviewee. In the piece about food they end with the conclusion that it is important to get the interviewee to reflect on what they are saying. To encourage them to become active participants in their own historical analysis, instead of it solely being the interviewer being the one who is analysing it. This is better for the power dynamic.

The code

Now I have already started writing a code of practice for the design aspect of this CDA but I have not really thought about what this would be for the oral history side. On reflection the system I am building for this CDA probably should have some type of code that accommodates it. And I believe that a point that was brought up by Graham in the reading group is a good starting. You see he mentioned that on of the oral history collections that was being reused had field notes attached to the recordings that would now be considered very unethical. Now of course these notes are a fabulous source for showing previous scholars attitudes to the method of oral history collection but they probably should not be digitised and on the internet for everyone to find. Graham therefore had them removed from the internet. This made me think that in the process of reusing oral histories there maybe should be the task of also doing ethical checks on the storage. A kind of mutual agreement that all oral historians keep each other in check since ethics is such a nebulous minefield.

OHD_BLG_0093 Oral History ➡️ Design

My masters in Multidisciplinary Innovation (MDI) taught me how design and its practices can be used in any field in order to create innovative solutions to complex problems. I believe that during this PhD I will use these techniques to help create a solution to the problem of unused oral history archives. This particular flow of knowledge I am completely aware of, however now I would like to discuss the reverse. How can oral history, its practices and its archives influence the world of design?

Let’s start with the reason oral history as a field exists. Oral history interviews are there to capture the history that is not contained within historical documents or objects. These histories often come from those whose voices have been deemed ‘unimportant’ by those more powerful in our society. It could be said that the work oral historians do is an attempt to equalise our history. However, oral histories, unlike more static historical objects and documents, are created in complex networks of politics, cultures, societies, power dynamics and are heavily influenced by time: past, present and future. Some oral histories take on mythological or legendary forms and are not necessarily sources of truth, but they do capture fundamentally human experiences that cannot be distilled into an object.

But how can this help the design world I hear you ask? Well, currently the design world is going through a bit of an ethical crisis. Ventures that started out as positive ways to help the world have brought us housing crises (AirBnB), blocked highways (Uber), crumbling democracy (social media etc.), higher suicide rates (social media), and even genocide (look at Facebook’s influence in Myanmar.) It’s all a big oopsie and demands A LOT of reflection. Why did this go wrong? How did this go wrong? What happened? Have we seen this before? How can we stop this from happening again?

We did a lot of reflection during MDI, but we also didn’t do enough. One, at the time we never shared any of our own reflections with the group and two, we now cannot revisit any of these reflections or the outcomes of our real life projects because they weren’t archived. The only documents I can access is my own reflective essays and a handful of files related to the projects, most of which solely document the final outcomes. This results in me only being able to see my own point of view and no process. Post it notes in the bin, hard drives no longer shared and more silence than when we were working in the same room. So what do we do if one of our old clients came to us asking how we got to the final report? Or after having implemented one of our designs are now experiencing a problem which they feel we should solve? Did we foresee it ? What are we going to do about it? I don’t know ask the others. It’s not my problem.

Now imagine this but on a global scale in a trillion dollar industry with millions of people (a relatively small proportion of the world) and very little regulation. And I am not just talking about Silicone Valley for once, but every global institution in the world. My supervisor told me that the World Trade Organisation once came to him asking for his help in setting up an oral history archive. The reason they needed this oral history archive was because they had all these trade agreements but everyone that had worked on them had retired and taken their work with them. They had the final outcome but not the process. Zero documentation of how they got there. Post it notes in the bin. They eventually did complete the oral history project but then did not have the documents to back these oral histories up because post it notes GO IN THE BIN. Whoops.

So, how did we get here?

In order to answer this question you need to be able to look back and see a fuller picture than your own point of view. We do this by not doing what the World Trade Organisation and MDI 2018/19 did. We create a collateral archive made of our post-it notes, digital files, emails etc. and we talk. We then put the collateral archive and the recordings of us talking together in one place. The reason we cannot rely solely on the collateral archive is because, as I said previously the documents cannot encompass the human experience to the extend that oral histories can. Also, not everything is written down some things will be exclusively agreed on verbally so the oral interview should (hopefully) fill in some of the blanks.

Once all this documentation has come together it needs to be made accessible to EVERYONE (with probably some exceptions.) This has two outcomes, firstly, it answers the question how we got here. People can analyse and reflect on the process in complete transparency. When something goes wrong we can look back and work out why. And secondly, in the case of design we now have a fantastic bank of ideas, a back catalogue of loose ends and unpursued trails of thought. Setting such a bank is already being examined in the field of design. Kees Dorst collaborated with the Law department at his university (I think) because he wanted to see how the Law department was able to access previous cases to help the present cases.

“Design […] seems to have no systematic way of dealing with memory at all” – Dorst, Frame Creation and Design in the Expanded Field p.24

In conclusion, people are increasingly aware that they need to capture their process in a constructive and archivable manner. Which is something I highly encourage for ethical reasons but also because archives are cool and you can find cool stuff in them. I am going to integrate this trail of thought into my PhD by being active in the creation of my collateral archive and also suggesting oral history interviews to be taken from all those involved.

(There is another reason why I would like to take oral history interviews of those involved, which hopefully is made clear in the ethics section of the site)

I hope that by integrating oral history into the design process it will push design into a more ethical space.

OHD_BLG_0096 The little tiny matter of ethics

Back during my MDI times I read a Buzzfeed that led me to the website Ruined By Design. It is the website for the book ruined by design by Mike Monteiro, which at the time I did not buy because the sample chapter was enough for whatever essay I was writing at the time. However as the start of my PhD draws ever closer I decided that it probably would be a good idea to read the whole thing. So I order the rather expensive zine and paid for it to be shipped all the way from America.

The hilariously designed anti-design book is on the whole very angry. Not too surprising as currently there are so many ex-silicone valley people speaking out against the designing happening in the valley (see the Netflix documentary The Social Dilemma.) But this one is a particularly feisty.

However, I like it. I like it a lot.

It starts with Monteiro discussing how designers need something like the Hippocratic oath because their work has such a huge impact on society. Fabulously, he comes up with his own code of ethics for designers. He, like any good designer, happily invites and encourages people to edit, improve and update.

So I think I am going to do it. I am going to put the code of ethics up on here and work out what I need to do in order to meet the code. I am not going to do it now though because it’s dinner time!