Tag Archives: Heritage

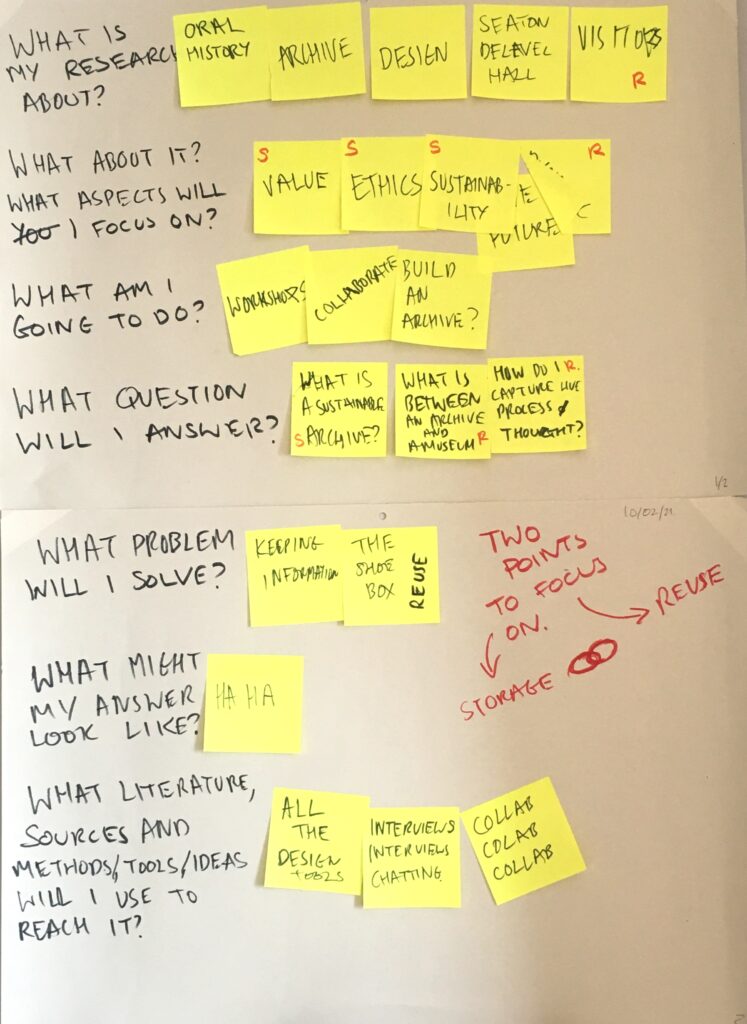

OHD_MDM_0028 Answer to questions about project

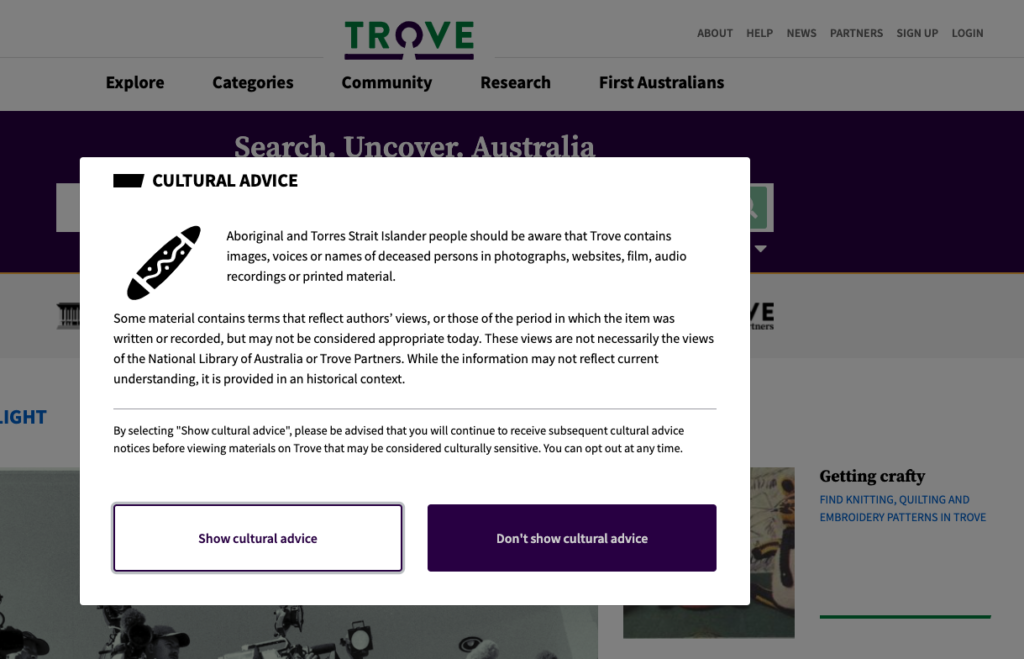

OHD_SSH_0142 Cultural Advice

OHD_PRS_0124 Presentation/Interview

Below is the presentation I had to do in order to be chosen as the student to complete this PhD. The interview took place on Feb 18th 2020 and the question I had to answer was, “What are the key challenges and opportunities [in this PhD] and how will you address them?”

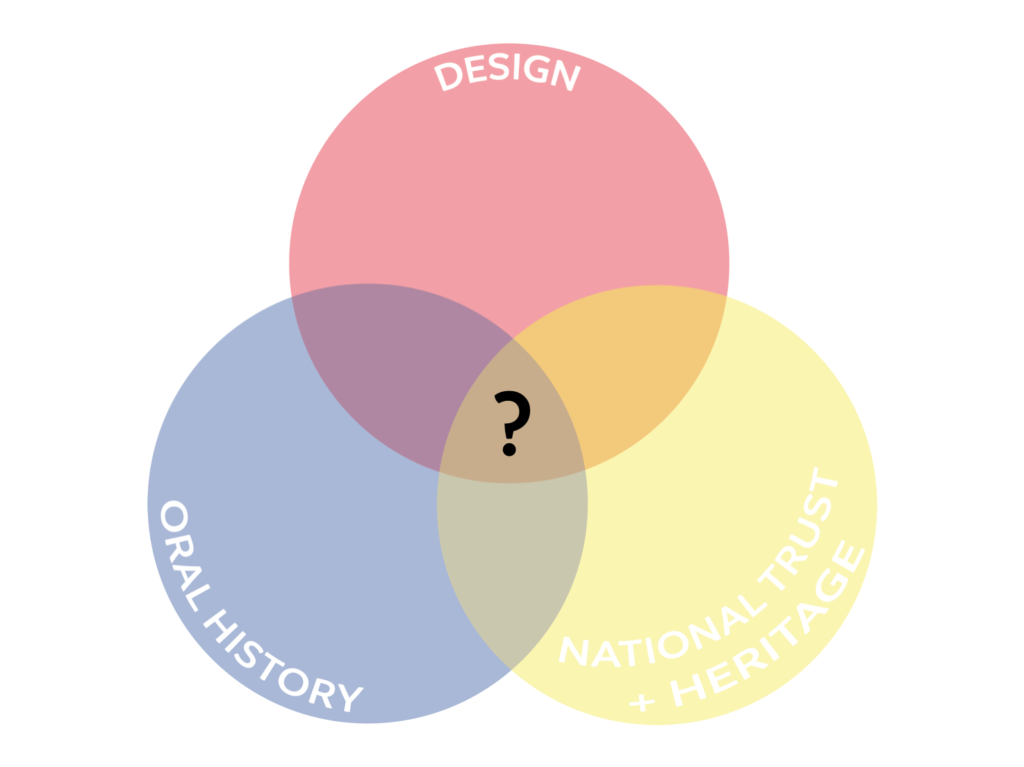

SLIDE ONE

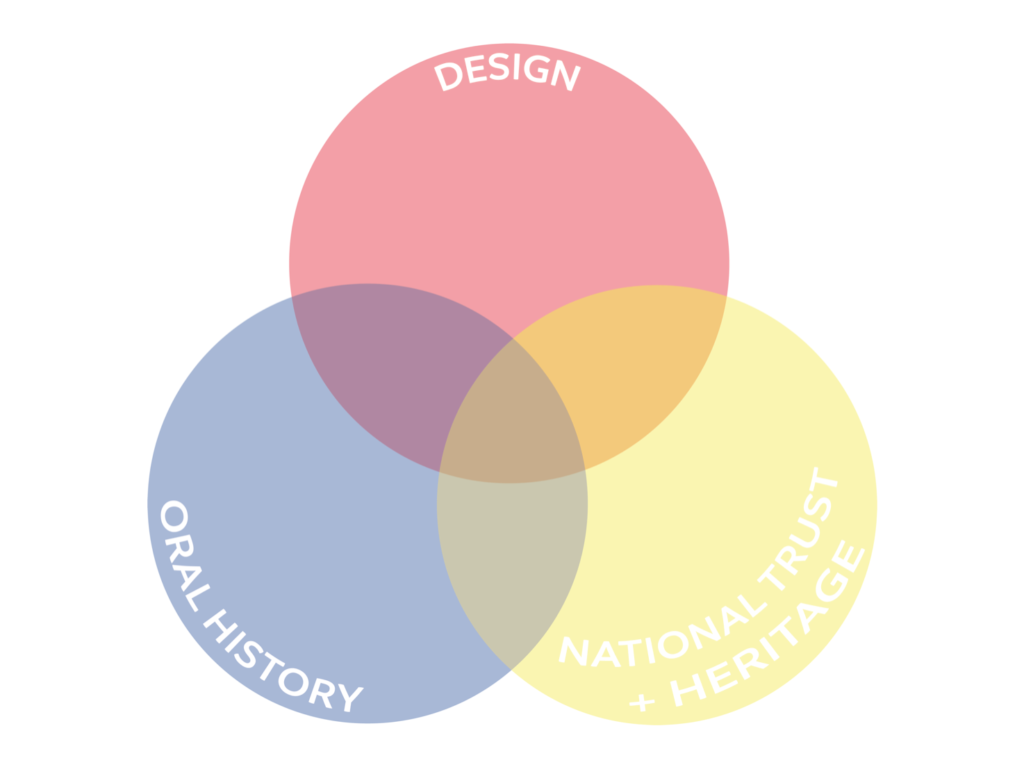

I have set this presentation up as a Venn diagram of three main parties of this CDA: National Trust and the heritage sector, Oral history and Design. In order to answer your question, I will navigate through the various sections of the Venn diagram identifying opportunities, challenges and how will address them.

SLIDE TWO

I think the first opportunity lies with the National Trust property Seaton Delaval Hall. If you observe the setting and history of the Hall you will find it to be the appropriate setting for this CDA. Firstly, the Hall is in the middle of a wide and rich community. Over hundreds of years the Hall and its inhabitants have contributed to this community and return the community has also given back with the most recent example being the money that was raise to help the National Trust take over the property. Secondly, it is a relatively young National Trust property. By that I mean that it has only been acquired by the National Trust in the last 11 years, meaning that until very recently; stories, memories and histories were being made at the Hall. Seaton Delaval Hall is therefore a perfect candidate for any oral history project, however a recent collaboration between the National Trust and MA in Multidisciplinary Innovation at Northumbria University makes the Hall the perfect location for this CDA.

SLIDE THREE

In May 2019 as part of the Rising Stars Project the National Trust came to Northumbria University with hope to collaborate in setting up a new oral history project. I was part of the team on the Multidisciplinary Innovation MA that was given the challenge of creating a new, an innovative method for collecting, archiving and displaying oral history. We started off by investigating methods of collecting group memories, as at first we found the National Trust’s current prescribed method of collecting oral history too formulaic. We concluded that due to the aforementioned setting of the Hall there should be a focus on reengaging the local community through this oral history programme. So we wanted to create a more participatory type of oral history that reveal a bigger picture of the Hall and created a sense of collective ownership of these histories. Instead of the “rather odd social arrangement” of the one-to-one interview, as Smith describes it in Beyond Individual / Collective Memory: Women’s Transactive Memories of Food, Family and Conflict, the team wanted to lay the power of the narrative with the participants instead of the interviewer. What we wanted to avoid is what the historian Lynn Abrams experienced while working on a project about women’s life experience in the 1950s and 60s. During that project she found that her position as an expert in women’s and gender history and implied feminist meant that her participants adapted their story to fit the wider feminist narrative. However, as our project progressed and the team dove further into oral history theory we started to understand the importance of individual interviews. Especially because during the testing of our group interviews we found that some people were less comfortable with the group setting and therefore would contribute less.

SLIDE FOUR

So, after three months of research, designing, testing, refining and testing again we developed two new group-interview methods alongside an incorporated individual interview. We also created several ways to display oral histories around the property, and potential new methods of archiving oral histories. Despite the high level of outputs the project only really scratched the surface, however it gave the opportunity for this CDA to exist in the first place. I view this project as the launchpad for this CDA. What it did was start an exploration into collective ownership and the role of community within the context of oral history at Seaton Delaval Hall and it brought together the various parties sitting here today. But most importantly it revealed that it would require more time and effort for it to be successful. This is especially the case with archiving, which was purposefully left open ended by the team, because as we producing all the previously mention outputs we discovered that oral history archiving is a very difficult problem.

SLIDE FIVE

Micheal Frisch discusses difficult problem this extensively in his paper ‘Three Dimensions and More’. He describes oral history archives as a shoebox of unwatched family videos and outlines various paradoxes that occurs in oral history archives. One of the paradoxes, the Paradox of Orality, refers to the inappropriateness of the reliance on transcripts in the context of oral history. Many oral historians, including Alessandro Portelli, agree that using transcripts in archiving reduces and distorts what was originally communicated by the interviewee. Although there are many archives that rely on transcripts, there are also archiving systems being developed that tackle this exact issue. Certain systems are already engaging with this paradox by using various forms of technology. Such as the Shoah Visual History Foundation, set up by the film director Steven Spielberg, where video testimonies of holocaust survivors are indexed, timestamped in English and can be navigated along multiple pathways. Another example is Oral History Metadata Sychronizer (OHMS) created at the Louie B. Nunn Center for Oral History at the University of Kentucky Libraries, which can be navigated by searching any word and it will jump to the exact moment that person is talking about the searched word (Boyd). I imagine throughout the CDA these systems, including the more analogue archives need to be explored further in order to uncover the opportunities for innovation. What we are specifically looking for is the opportunity to create a system that is not driven by technological advancements, but by a desire to change the culture of how we use archives.

SLIDE SIX

Currently, we use all types for archives in a static way, which is the opposite to how we treat history. Not only are we constantly making new history through the passage of time, our attitudes towards history constantly changes. For example the global discussion surrounding artefacts in the British Museum or even attitudes towards mining. Recently I worked with the arts and education charity Hand Of at the Durham Miners Hall with children from the local area. Working with these children you see that they view mining through a completely different lens to the generation that came before. While you and I might associate mining with the miners’ strike and the deindustrialisation of the UK, these children view mining as something from the pass, something important to the previous communities but ultimately something unsustainable and bad for the environment.

The static nature of the archives is in complete contradiction to how people experience history. I believe this CDA is looking for is a more sustainable and dynamic preservation of stories. A system that taps into the ever changing zeitgeist reflected in its visitors instead of keeping everything frozen in time.

Well the CDA is called the ‘Oral history Design’. In my eyes I see design the provider of tools for exploration, with Seaton Delaval Hall providing the test subjects. This CDA would not be possible if it was not for the resources that the National Trust has to offer. Those resources being the visitors, the volunteers, those who provide the histories and the team working at Seaton Delaval. I believe that in order to create a system that is truly sustainable it needs to be tested at every point of the process and the collaboration with the National Trust gives us that opportunity.

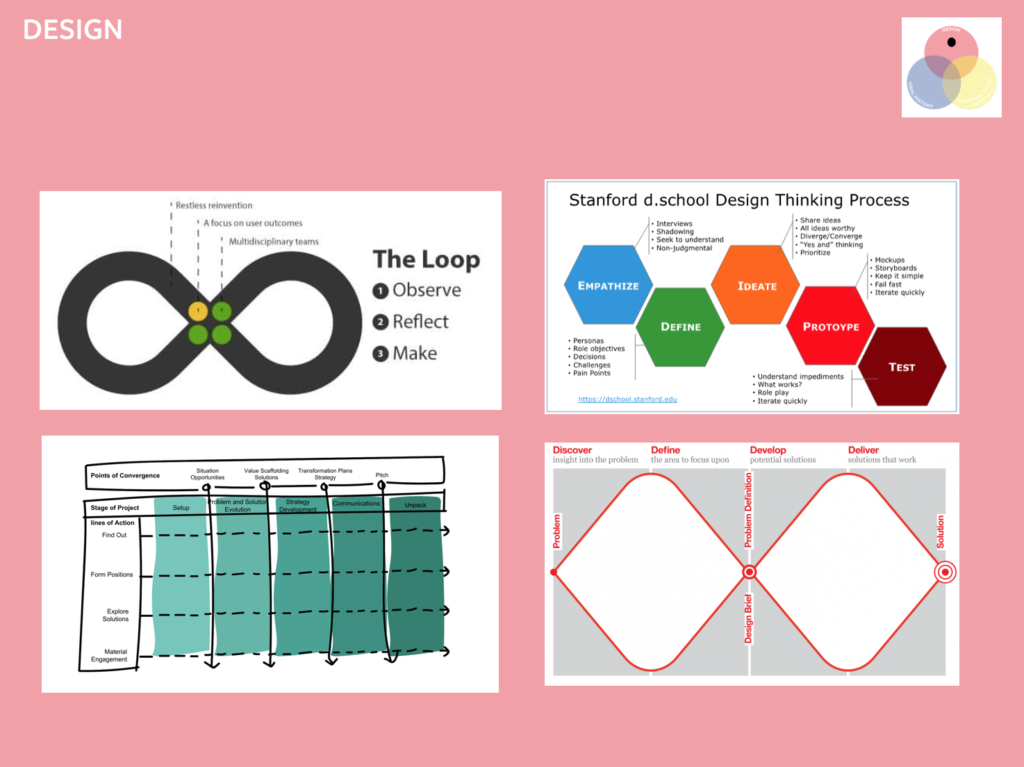

SLIDE NINE

The challenge however is finding the appropriate design tools. Design intervention and the use of design thinking tools can deliver high rewards but it can also cause considerable damage if not use responsibly. Not only do I expect to do more research into design methods on top of the ones I am already familiar with. I also expect to constantly be reviewing, adapting and modifying the tools and design process as project progresses. This is something that is highly encouraged by many people in the field of including the Kelley brothers, from IDEO, who openly invite people to adapt their methods and Natascha Jen from Pentagram, who argues that design thinking is more of a mindset, not a diagram or tool. Within this CDA this might evolved into regular reflection on the process both from myself as the student and from the other parties involved. All of this is especially important because the collaboration between design and oral history is a relatively new and unexplored territory.

SLIDE TEN

This unexplored territory, however gives the CDA opportunity to explore something in addition to the creation of a new archiving system; the methodology behind cross-disciplinary work within the academy. Cross-disciplinary work is nebulous and struggles to be categorised within the academic system. As I found throughout my MA there is a lot literature that talks about interdisciplinary, transdisciplinary, multidisciplinary, cross-disciplinary work. These papers, books and articles talk about bringing various parties together in order to solve a problem but it is nearly always in the context of business or social enterprise. The CDA will therefore offer us the opportunity to research and experience multidisciplinary or cross-disciplinary work within the context of a university.

However, cross-disciplinary, transdisciplinary, interdisciplinary, multidisciplinary work, whatever you would like to name it, does come with its fair share of challenges. I am familiar with this as during my MA I had to work in an 18-strong team of people from a diverse range of ages, ethnicities, nationalities and socio-economic backgrounds and different fields of work. Throughout the year it was clear that one of our biggest barriers was communicating across these differences. It often felt like I was speaking a completely different language, which sometimes was the case, as certain ambiguous words were perceived differently depending on the person’s background. I predict this to happen throughout the CDA, not only across the design and oral history but also with the National Trust and any additional parties that might be involved.

SLIDE ELEVEN

It is essential that we have as many of these cross-disciplinary conversations as possible. Roberto Verganti, in his book Design-driven Innovation, refers to these types of cross-disciplinary conversations as a ‘design discourse’ – experts from different backgrounds exchanging information. Verganti finds this to be essential in design-driven innovation, an innovation strategy that pursues change through a reinvention of the meaning of a product or system instead of relying of technology. Which is exactly what this CDA is looking for.

This design discourse needs to be managed and organised efficiently, which I feel confident I am capable of doing due to working in teams throughout my professional and academic work. Especially thanks to my MA and my work with Hand Of and teaching for the early English programme Such Fun! I know the importance of clear communication and disciplined organisation. I imagine that I as the student of this CDA, I will have to take a project manager-esque role in order to float between the different disciplines, communicating progress and finally managing expectations.

SLIDE TWELVE

And that really is the crux of it all, managing expectations, because you cannot guarantee anything. For all we know the answer to design oral history archives is – don’t, National Trust’s prescribed archiving method of electronic cascading files does the job perfectly well. For now this CDA is exploring the unknown, but that is what I like about it. I spent three years in a Goldsmiths art studio exploring the unknown, then I did an MA do to more targeted exploration of the unknown and now I have a narrow it down again in applying for this CDA. Exploring the unknown is full of opportunities and challenges, but you have to do it in order to find them and I very much like to do it.

The feedback a got on my presentation was good, however I did not do as well on answering the questions. This is a completely fair judgement as I felt slightly unprepared. I think it is important that I start planning out the steps I will be taking throughout the three years and deadlines for certain outputs.

OHD_LST_0123 questions

Here is a collection of questions I have asked myself concerning the topic of my PhD both big and small.

How do we handle the racism that exists in the archives? Date: 16/06/2020

What do we do with unused interviews? Date: 19/06/2020

Do we need to reevaluate how we create oral historians in order to ensure more equality within the sector? Date: 16/06/2020

What is the difference between a documentary and an oral history project or article? Are they not both curated equally? Is the only true form of oral history stuck unedited in the archives? Date: 20/07/2020

How can we utilise Gen z and the digital natives in oral history archives? What might the pitfalls be? Date: 21/07/2020

Do I have a problem with the word history in the context of oral history interviews? Date: 21/07/2020

Are there any aural oral history papers? If so where are they and why aren’t there more of them Date: 01/10/2020

How does the archive function in a ‘knowledge/data’ economy? Date: 23/10/2020

Do filters for the public limit or increase accessibility? Date: 23/10/2020

Are we looking for an ‘archive’ or a completely new system? Date: 23/10/2020

What should an archive be like during an pandemic? Date: 08/02/2021

How does “Material History” work in the context of oral history? Date: 08/02/2020

Do we get bogged down in the ethics? Date: 16/02/2021

What is our relationship to the ‘public’? Date: 16/02/2021

What does digitization replace? Date: 10/03/2021

Are result lists the problem when it comes to searching? Date: 12/02/2020

What does it mean if people can’t remember? When people are scared of not being able to remember? Date: 16/03/2021

Where does intertextuality and oral history theory end and academic snobbism begin? Date: 16/03/2021

Is having an oral history recorded like donating your body to science? Date: 16/03/2021

What do the interviewees think about reuse? Date: 16/03/2021

How do we take stuff back to the interviewee? Date: 16/03/2021

How do you build a community? Can you build a community? Or do they only grow naturally? What is the balance between setting up/designing a community and having one naturally occur? Date: 30/04/2021

Can the digital ever be transparent if those who make it are from one exclusive group? Date: 11/05/2021

Do we trust archives? Date: 11/05/2021

Does our idea of original need to change? Date: 11/05/2021

Can you democratise history outside of a democracy? Date: 07/05/2021

OHD_PRS_0122 Staying flexible: how to build an oral history archive

The second conference paper I presented. This one went better than the first one so that is positive.

Slides

Script

[slide two]

This is Seaton Delaval Hall. This National Trust property can be found in Northumberland just up the coast from Newcastle. Built in the 1720s the hall and its residents, the ‘Gay Delavals’ became renowned for wild parties and other shenanigans.

[slide three]

In 1822 the hall went up in flames severely damaging the property. This history is well represented in the collection that is housed at the hall.

[slide four]

What is less represented, however, is the hall’s more recent history: the community that looked after the hall after it burnt it down, the prisoner of war camps, and the medieval themed parties that the late Lord Hastings threw after the hall’s restoration.

For my PhD I will attempt to solve this issue of missing history by building an oral history archive. Oral history is a tool that has been employed many times to help represent the underrepresented in history. The challenge however is to build an archive with these oral histories. To help me explain how I am approaching this challenge I will use a metaphor.

[slide five]

This is a Ferrero Rocher. Through this yummy treat I will attempt to explain my project and the various layers of the process that need to be considered and analysed in order to be able to build an affective oral history archive.

[slide six]

The Hazelnut AKA a new storage system

The metaphorical hazelnut and core of this project is this storage system that will hold the oral histories I record. Why do I call it a storage system and not archive? I say this for three reasons, firstly because archives and oral history recordings are not the best of friends.

[slide seven]

The original framework that we use to structure and build archives is, and has always been, based around archiving mostly written documents. Searching through this type of material is easy because their content is visually apparent. These days you can, if they have been digitise, word search the documents very easily.

[slide eight]

Oral histories recordings (not the transcripts) struggle to fit into this framework, because their content can only be accessed if you sit down and listen to them. Listening back to these recordings can take a lot of time and can be hindered by outdated technology. This mismatch between the material and the place where it is stored often discourages people to reuse oral histories.

[slide nine]

I think the oral historian Micheal Frisch puts it best when he called oral history archives “a shoebox of unwatched home videos.” The content is there but the viewing a specific moment is an arduous task. Mining the hall’s community for stories and throwing them into a shoebox is exactly what I want to avoid with this PhD.

[slide ten]

At Seaton Delaval Hall I want to create a storage system that broadens access to and actively encourages reuse of the oral histories, in order to support the community that has looked after the hall for so many years.

The second reason I say storage system instead of archive is ….

[slide eleven]

because currently archives are struggling with adapting to advancing technology. In recent years there has been a push to digitise archives with the COVID-19 pandemic giving this process an exceptional boost.

[slide twelve]

However, this digitisation requires a lot of resources like money, time and manpower that many archives, especially smaller ones, simply do not have.

[slide thirteen]

In addition, what this push to digitise does, which it does in many sectors, is attempt to replace a human with a robot, who in my opinion is simply not up to the task. Typing into a search bar is not the same as asking an archivist for help.

[slide fourteen]

While a search bar is a tool one uses when researching, the archivist becomes a fellow researcher, making room for far more flexible and creative exploration.

[slide fifteen]

Thirdly, archives are rather static in comparison to the world outside of their brick and mortar walls.

[slide sixteen]

Especially in the last year there has been increasing pressure to review how we present our history as a society. This dynamic debate is not reflected in the way we store our historical documents.

[slide seventeen]

This limited reviewing and updating of our archives actually makes it harder to do research. The most obvious instance being how certain keywords become outdated over time, which is something that is especially prominent in the archiving of minorities’s histories such as LGBTQA+ and Black history.

[slide eighteen]

The way we traditionally build an archive does not fit with contemporary society. Archives were initial set up to preserve one view of history in one type format. They did not leave room for new technologies and new points of view. Now, archives are attempting to change this by rather awkwardly moving into the digital space without truly questioning how these digital tools affect the archiving process and researching in archives.

In order to create a new storage system I wish to let go of these traditions, these symbols and languages that we use to navigate oral histories, archives and the digital.

[slide nineteen]

I want to start with a blank canvas and build a storage system that not only reflects the technology and views found in society but also makes room for any further developments in these areas. Now, the next question is: how we might go about building this new system?

[slide twenty]

The chocolate filling AKA working together without killing each other

[slide twenty-one]

AKA collaborating! A truly fabulous buzzword that works very well in funding applications but in reality is really difficult to do. Why? Well, every field of research has its own type of

[slide twenty-two]

‘disciplinary upbringing.’

[slide twenty-three]

When I say ‘disciplinary upbringing’ I am referring to the lens that each field views things like language and methods of work through. In other words the

[slide twenty-four]

‘here we do things this way’ attitude.

[slide twenty-five]

When people collaborate across disciplines they bring this lens, this disciplinary upbringing, with them so when the work starts everyone is viewing the challenge through separate and different lenses. This can lead to a lot clashes and plenty confusion.

So how do you solve this?

[slide twenty-six]

You could just say that people should leave their disciplinary upbringing at the door but that never works.

[slide twenty-seven]

Instead I intend on using these disciplinary upbringings to the advantage of the creative process by encouraging people to be open about them and in some cases even exaggerate them a bit. What this does is bring to light the various

[slide twenty-eight]

‘creative tensions’ that are present in the collaboration.

[slide twenty-nine]

For example in the context of this project where we have a collaboration between the fields of oral history, design and heritage you can find many creative tensions that are the consequence of differing disciplinary upbringings.

[slide thirty]

Between oral history and design there is the tension of the medium of communication; historians like writing and designers love a good visual.

[slide thirty-one]

I can tell you from experience that design and heritage work at dramatically different speeds. One of design’s key philosophies is “fail fast”, which is definitely not something would be mentioned in a National Trust meeting.

[slide thirty-two]

Finally, between oral history and heritage we find possibly the most challenging of creative tensions, which is differing opinions on the representation of history.

[slide thirty-three]

It is important to identify these creative tensions because they highlight issues that might have otherwise gone unseen if everyone had just been polite and kept their mouth shut.

[slide thirty-four]

Once they have been determined they function as a great source of information. This information needs to be drawn out through thorough questioning. It is essential to discover why the tension exists and how it might inform the creative process.

[slide thirty-five]

This does however mean that sometimes you might have to ask what seem like silly and obvious questions, because your disciplinary upbringing to begin with blocks you from fully understanding where other people are coming from. To complete the questioning to its fullest potential it is necessary to unpack any confusion no matter how small or trivial they might seem.

[slide thirty-six]

However the most fundamental thing within this chocolate filling of collaboration is — listening. One must always remember that you are not there to defend your disciplinary upbringing, you are there to solve a collective problem. When identifying and questioning creative tensions everyone must listen to all of those collaborating.

[slide thirty-seven]

Overall the chocolate filling represents something that can be very difficult, but with open minds, questioning and listening can be exceptionally fruitful.

[slide thirty-eight]

The Crunchy shell aka beyond the toolkit

A Ferrero Rocher is not complete without its crunchy shell and neither would this project. The crunchy shell in this context represents the legacy of the project. It is important to me that the project and the storage system does not end with the completion of this PhD.

[slide thirty-nine]

In order to avoid this I and everyone involved in the project shall thoroughly question and analyse the process of building this storage system. We need to reflect on what worked and what didn’t work. This questioning needs to be beyond which workshop activity was fun and whether we had enough time.

[slide forty]

What we need to do is extract questions that will help someone else set up a similar project. So instead of creating a rigid set of instructions with painfully particular processes, we offer future oral history projects questions that they must ask themselves before, during, and after the project. This hopefully will allow them to adapt the process to their needs and encourages them to think more creatively.

[slide thirty-nine]

Conclusion

Now I completely recognise the irony of me slamming the idea of a rigid sets of instructions and then ending on a how-to guide, but in my defence I had the title before I fully wrote the paper so please forgive me.

How to build an oral history archive

- Let go of your preconceptions of what an archive is (and also what the digital is)

- Work together by allowing creative tensions to occur and be questioned

- Reflect on your process and extract questions for future projects

The true aim of this how-to is to make sure that we do not end up in the same position we are now, where our archives no longer reflect society. The world is only going to get more complicated so if we do not leave room for questioning and change, archives are always going to be behind. This would be a disaster as archives on a macro scale are the keepers of our history and (in theory) hold the foundations of our collective identities as a people. On a more micro scale I have personally always found comfort in how archives keep documents that show everyday humanity, like a postcard to a fellow artist or a writer’s note to a partner.

So here is my how-to on making an oral history archive. Take it with you, try it out, tell me if it worked. I am going to do the same and probably change it many times in the next three years.

OHD_PRS_0120 The Unseen: Maintenance Labour on Heritage Sites

// “To invent the sailing ship or steamer is to invent the the shipwreck. To invent the train is to invent the rail accident of derailment. To invent the family automobile is to produce the pile-up on the highway.” (Virilio, P. (2007) The Original Accident. Cambridge: Polity, p. 10)

// To have an interactive game in your museum is invent the “out of order” sign and

// to open a heritage site is to invent the tape which communicates “sorry this part of the house is closed due to restoration”.

// Any creation brings with it everything that could possibly go wrong and also all the things that need to be done ensure things do not go wrong.

// This includes a curated visitor experience on a heritage site. Many things can go wrong, so there are a lot of things to do to ensure things run smoothly: are there enough volunteers to show visitors around, are the toilets clean, is the cafe well stocked, is the art collection available to view, are the gutters clean so they do not flood in case it rains. And for National Trust sites there is added pressure because the visitor experience also needs adhere with the expectations people have of National Trust sites.

// The theme of this conference is ‘experience’ and I would like to talk about

// the labour necessary to allow an experience to be experienced on a heritage site

// specifically the maintenance labour, and how

// maintenance labour’s position in society radically influences the running of heritage sites and

// how this effects the work I am doing with my PhD which is in collaboration with the National Trust property Seaton Delaval Hall.

// I think we need to start by understanding what maintenance labour is

// I am going to do by introducing you to three characters with three stories that will help me illustrate the nature of maintenance work and the position it holds in society: Jo, who is part of my supervisory team, the collector and entrepreneur Robert Beerbohm, and the artist Meirle Laderman Ukeles.

// Jo works for the National Trust as a curator among other things, titles are a bit vague in the Trust so I am not completely clear on what they do, this is also not a picture of them, obviously. They told me a story of when they were walking around a Trust property together with their predecessor. Their predecessor decided to point out some of their biggest achievements, which was not a new cafe or an exhibition but

// a window frame that look exactly like it did when they started. This is a perfect embodiment of maintenance work, because if the predecessor had not pointed the window frame out to Jo, they admitted that they probably would not have noticed it at all. In this window there is no evidence of the predecessor work, their work is completely invisible which is common for maintenance work.

// We just expect our streets to not be full of rubbish, the toilets in our buildings to be clean, fresh water to come out of our taps. We often do not see, or wish not to see the effort behind these things.

// So they live an invisible life until things go wrong,

// which brings me Robert Beerbohm.

In the book How Buildings Learn Stewart Brand tells the story of the collector Robert Beerbohm, who had over million dollars’ worth of comic books and baseball cards stored in

// a warehouse in California. The roof had a known drainage problem but the building owners had not prioritised this to be fixed. One day there was particular heavy rain fall and the roof leaked terribly flooding the entire warehouse, damaging all the collectables. Beerbohm lost everything.

// If we compare the warehouse to the window in the Trust property, we see how maintenance only becomes visible once it has failed or not been done at all. The window was maintained but there are no traces of the work put in, while the warehouse was not maintained and the results are obvious and catastrophic. Maintenance only becomes visible in a negative way.

// As Brand says maintenance work is “all about the negative, never about rewards.” If the roof had been fixed and the roof did not collapse Beerbohm would not have technically gain anything but he also would not have lost anything either. He would however not be aware of the lack of loss because nothing happened. All maintenance offers is stability, no tangible reward, in fact Beerbohm would have lost money on fixing the roof and that is exactly how it would have felt, as a loss. Maintenance always feels like a loss and a waste because it takes time, work and money to do it and in the end you have nothing new to show for it. You just go back to where you started. You keep the window frame exactly the way it is. And then once it is done you have to start all over again.

// And yet as Brand concludes “the issue is core and absolute: no maintenance, no building.”

// The artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles,

// wrote a manifesto titled

// Manifesto for Maintenance Art 1969! And in it Ukeles presents this idea of society dividing up labour into two systems:

// the development system and the maintenance system. The words Ukeles uses to describe the maintenance system

// “Keep the dust off, preserve, sustain, protect, defend, prolong, renew” all fit within the tales of Jo and Beerbohm, maintenance is about protecting, prolonging and generally keeping the dust off things. But it is how Ukeles describes the development system that really puts things into perspective:

// “pure individual creation; the new; change; progress; advance; excitement”. These are some really fun buzzwords. You are going to want to get some of these into your funding application.

// And that is exactly what Ukeles is trying to tell us with her manifesto, in society we value development over maintenance. When child comes home from school they want to talk about their fabulous new sculpture made from a milk carton sellotaped to piece of cardboard with stuck on googly eyes.They are not going to tell you about how they tidied up the classroom after they had finished crafting their masterpiece to make it look exactly like it was before they got out the scissors and glue. We do not care about maintenance. Maintenance is less fun, as

// Ukeles says “Maintenance is a drag; it takes all the f***ing time”. And because we do not care for maintenance work means that we do not reward people for maintenance work.

// In her art Ukeles discusses the unpaid domestic labour she has to do as a mother but also the labour carried out by the sewage department for example, which is also not going to make you the big bucks.

// To quickly summarise,

// maintenance is often completely invisible because the outcome makes things seem to ‘stay the same’,

// it is deeply undervalued in society due our obsession with development,

// and yet it is utterly essential. This is the case everywhere and

//heritage sites are no exception.

If you work on a heritage site two of the hottest topics of conversation is not what the soup of the day is but

// volunteers and funding and both are severely affected by our societies rather negative view of maintenance work.

To start with let’s look at volunteers.

// Just like we rely on maintenance workers to remove the rubbish from our streets, fix our pipes, and clean our nappies, we all rely on

// National Trust sites to look like National Trust sites, if they don’t we get angry. Let’s take a more specific example –

// a National Trust garden. A National Trust garden has a look, it is essential that it gets achieved every year for visitor satisfaction, which means it often is achieved every year.

// So we are kind of going back to the window. Every year the garden looks the same, just like the window, and this stability erases the traces of labour giving the illusion of a magical garden that always looks this great. But this does not just happen.

// It requires a lot of work and who does this work?

// A couple of head gardeners (a classic maintenance job)

// and mostly, because it is the National Trust, volunteers, literally people who do not get paid to do the work.

// Now volunteering is a fantastic opportunity for people to build a community and keep themselves generally occupied, I cannot deny that. But you can also not deny that a volunteer doing gardening is putting a professional gardener out of a job.

// In the paper Making usable pasts: Collaboration, labour and activism in the archive, an archivist, Carole McCallum, from Glasgow Caledonian University (GCU) is quoted saying that she did not want bring volunteers into the archive because it would put a professional out of a job.

// In another paper on ‘punk archaeology’ the author writes “If people are willing to undertake some forms of archaeological work for free, it is possible this will impact on the value of paid work in the sector.”

// The use of volunteers on heritage sites creates a vicious cycle, it starts with

// maintenance labour being undervalued,

// maintenance jobs then are the first to become unpaid volunteering opportunities, and

// because the work is now done for free the value of the maintenance work drops again because who would paid someone to do a job when another does it for free.

// Moving on to funding. It is common knowledge that heritage sites like the majority of organisations in the culture sector rely on money from big funding bodies.

// Funding bodies therefore have a lot of decision power over what gets money and what does not. If you go to the National Lottery Heritage Fund website and go to the “Projects we’ve funded page” and type ‘develop’ into the search bar you get two pages of results. Now this is not a lot but that is because it just searches titles.

// Nevertheless if you type in maintenance you get one hit. This is no the most solid evidence and I am looking to do audit of the types of projects that have been funded by large funding bodies. But for now it will have to do, it hints at a difference in value. However, there is one other thing, in this single maintenance hit the title includes the term restoration. It is important to point out that restoration and maintenance are not the same thing.

// In How Buildings Learn Stuart Brand quotes John Ruskin, “Take proper care of your monuments, and you will not need to restore them. Watch an old building with an anxious care, guard as best you may, and at any cost, from every influence of dilapidation.” Restoration is only necessary when maintenance fails.

// Now if you type restoration into the search bar you get many pages of projects. The National Lottery Heritage Fund gives a lot of money to restoration projects. You see restoration and development deliver the same amount of satisfaction, the before and after is impactful and makes everyone go ‘ooh’ and the funding bodies can go home feeling that they made a difference. But if we follow Ruskin then they would not need to do this if they funded maintenance. But as we know it is not sexy and above all it is endless. You cannot fit maintenance into a time limited project and the way the funding systems works we have to work in terms of projects and tangible achievements, so funding maintenance is not an option.

// So to summarise our undervaluing of maintenance in society has led to

// an increase in volunteers replacing paid jobs and

// funding bodies to focus on development and restoration above maintenance projects. And this is where we get to the real painful part, because this is not going to change. We live in an extreme capitalist society which has not changed much since

// Ukeles pointed out how we do not about care about maintenance work more than fifty years. Look at how we treat our key workers. We clapped for them for a bit

// but now the vacancies in care and hospitals speak for themselves and you cannot avoid signs asking you not to abuse the staff in most place’s where key workers operate.

// So society is not going to change but I still have to finish my PhD by 2025 so I will have to work within this framework.

// My project is specifically looking at how to sustain (re)use of oral history recordings on heritage sites and I am working in collaboration with Seaton Delaval Hall. So basically I am designing a type of archive because currently archives are not oral history recordings’ best friend.

// What I am doing is 100% part of

// the development system, and my collaboration partners, the staff at Seaton Delaval Hall are the

// maintenance workers who have to keep the dust off my creation. Now of course they could simply

// throw my work into the bin after January 2025 but for my own sense of pride I would like to avoid that. I believe this means I must understand and incorporate ideas of maintenance into my work.

// First thing I need to do is make something

// realistic. Now that sounds obvious but currently people are very obsessed with getting technological solutions to problems,

// which is great but not very realistic.

// Not a lot of people have the capacity to maintain super complicated digital softwares and considering the National Trust’s reliance on volunteers, who unlikely to have significant computer coding skills, they do not have the labour capacity to handle the maintenance of certain technological solutions. I also need to be realistic when it comes to

// the time and money people are able to dedicate to maintaining my design. Understanding where my work can fit into the day-to-day running of the Hall is crucial otherwise it is likely to constantly be put on the back burner until there finally is a ‘good time’ to work on it, which given the pressures on the staff is unlikely to be a regular occurrence.

// The second thing I need to do is make it adaptable.

// Things change all the time and before you know it you are in a global pandemic.

// Which is why I imagine a certain level of DIY needs to be part of my work,

// allowing the maintainers of my design to adapt it to their current needs rather than having to bend to my old requirements.

// Currently I hope that by doing a placement at the Hall I will be able to better understand the needs and desires of those who will be keeping the dust off my work and then be able to make something that fits into the maintenance system at the hall instead of imposing my development system onto them.

OHD_LST_0119 words

Acousmatic Sound

Acousmatic sound is sound that is heard without an originating cause being seen. The word acousmatic, from the French acousmatique, is derived from the Greek word akousmatikoi (ἀκουσματικοί), which referred to probationary pupils of the philosopher Pythagoras who were required to sit in absolute silence while they listened to him deliver his lecture from behind a veil or screen to make them better concentrate on his teachings.

Archivism

The act of moving something from the everyday to the space of archive.

Affective Computing

Affective computing is the study and development of systems and devices that can recognise, interpret, process, and simulate human affects. It is an interdisciplinary field spanning computer science, psychology, and cognitive science. One of the motivations for the research is the ability to give machines emotional intelligence, including to simulate empathy. The machine should interpret the emotional state of humans and adapt its behaviour to them, giving an appropriate response to those emotions.

Aufhebung

In Hegel, the term Aufhebung has the apparently contradictory implications of both preserving and changing, and eventually advancement (the German verb aufheben means “to cancel”, “to keep” and “to pick up”).

Authorised Heritage Discourse

The creation of lists that represent the canon of heritage. It is a set of ideas that works to normalise a range of assumptions about the nature and meaning of heritage and to privilege particular practices, especially those of heritage professionals and the state. Conversely, the AHD can also be seen to exclude a whole range of popular ideas and practices relating to heritage.

Brick and Mortar Archives

A rather more elegant term for archives that are stored in buildings. Because it is important to note that digital archives are also very physical.

Content Drift

When the content of a page has been moved around on the internet causing certain links to no longer be attached to that specific page.

Counter-reading

Counter reading is when you identify the gaps in an archive, analyse why they are exist and combined this with further contextual history in order to fulfil your research.

Data Degradation

Data degradation is the gradual corruption of computer data due to an accumulation of non-critical failures in a data storage device. The phenomenon is also known as data decay, data rot or bit rot.

Disciplinary Upbringing

The separate lenses through which individuals from different fields of work view and approach things like: problem solving, language, and general practice.

Drive By Collaboration

Collaborating but only a trivial amount of time and often to fulfil a funding requirement.

Ego Documents

The word ‘egodocument’ refers to autobiographical writing, such as memoirs, diaries, letters and travel accounts. The term was coined around 1955 by the historian Jacques Presser, who defined egodocuments as writings in which the ‘I’, the writer, is continuously present in the text as the writing and describing subject.

GAFA

Acronym for Google, Apple, Facebook and Amazon. The tech giants.

Historical Imagination

A tool use by historians to put themselves into the shoes of the historical figure they are investigating or imagining themselves in the streets of a certain historical setting. It can be helpful to bring together separate ideas and bring the history back to life as such.

GLAM

GLAM stands for Galleries, Libraries, Archives and Museum.

Link Rot

When the webpage attached to a link can no longer be found when you click on it and instead offers you the message “Page not found”

Liquid Architecture

Liquid architecture is an architecture that breathes, pulses, leaps as one form and lands as another. Liquid architecture is an architecture whose form is contingent on the interest, of the beholder; it is an architecture that opens to welcome me and closes to defend me; it is an architecture without doors and hallways, where the next room is always where I need it to be and what I need it to be.

Marcos Novak in “Liquid architecture in Cyberpace”

Media

Originally coming from the word mediator.

Media Archaeology

Media archaeology or media archeology is a field that attempts to understand new and emerging media through close examination of the past, and especially through critical scrutiny of dominant progressivist narratives of popular commercial media such as film and television. Media archaeologists often evince strong interest in so-called dead media, noting that new media often revive and recirculate material and techniques of communication that had been lost, neglected, or obscured. Some media archaeologists are also concerned with the relationship between media fantasies and technological development, especially the ways in which ideas about imaginary or speculative media affect the media that actually emerge.

Media Literacy

Media literacy encompasses the practices that allow people to access, critically evaluate, and create or manipulate media. Media literacy is not restricted to one medium. Media literacy education is intended to promote awareness of media influence and create an active stance towards both consuming and creating media. Media literacy education is part of the curriculum in the United States and some European Union countries, and an interdisciplinary global community of media scholars and educators engages in knowledge sharing through scholarly and professional journals and national membership associations.

Multivalence

Multi-valents, many values, the holding of different values at the same time without implying confusion, contradiction, or even paradox. (Term coined by Michael Frisch.

Open Access

Open access (OA) is a set of principles and a range of practices through which research outputs are distributed online, free of cost or other access barriers.

Participatory Action Research (PAR)

Participatory Action Research (PAR) has been defined as a collaborative process of research, education and action explicitly oriented towards social transformation. Participatory Action Researchers recognise the existence of a plurality of knowledges in a variety of institutions and locations. In particular, they assume that ‘those who have been most systematically excluded, oppressed or denied carry specifically revealing wisdom about the history, structure, consequences and the fracture points in unjust social arrangements’. PAR therefore represents a counter hegemonic approach to knowledge production.

Post Private

The age of high surveillance which we live in now.

Reference Rot

When links in footnotes on longer are attached to the reference. This is often due to link rot or content drift.

Software Rot

Software rot, also known as bit rot, code rot, software erosion, software decay, or software entropy is either a slow deterioration of software quality over time or its diminishing responsiveness that will eventually lead to software becoming faulty, unusable, or in need of upgrade. This is not a physical phenomenon: the software does not actually decay, but rather suffers from a lack of being responsive and updated with respect to the changing environment in which it resides.

Taxonomy

The science, laws, or principles of classification.

Vox Pox

Coming from the latin vox populi, it refers to a short interview with a member of the public.

Wikidata

Wikidata is a collaboratively edited multilingual knowledge graph hosted by the Wikimedia Foundation. It is a common source of open data that Wikimedia projects such as Wikipedia, and anyone else, can use under the CC0 public domain license. Wikidata is powered by the software Wikibase.

OHD_BLG_0041 The winds of change are blowing…

I feel there is a change in the wind… Specifically people are starting to think more long term about their projects, they are becoming more archive focused. This is not too surprising there is a reason my PhD is happening now and not earlier. Timing is everything when it comes to research and people from different fields have invested in this PhD which they would not have done if it was a ridiculously radical idea. But crucially funding bodies also seem to be changing their tune slightly. I was pointed in the direction of the National Heritage Fund’s new programme, Dynamic Collections. According to their new campaign:

Our new campaign supports collecting organisations across the UK to become more inclusive and resilient, with a focus on engagement, re-interpretation and collections management.

THE NATIONAL HERITAGE FUND

Sounds pretty promising if you ask me…

OHD_BLG_0042 What do you mean not digital?

Whenever I mention my ideas for analogue archiving solutions to anyone the reaction I get is a blank stare shifty follow by a change in subject. When I was venting about this recurring experience to my mother, she did not seem surprised; “what do you except people see the digital as the future?” She is correct this is what people believe but the ‘future’ is a rather nebulous concept and it is important to manage expectations – how far is the ‘future’? If you take what is written in The shock of the old: technology and global history since 1900 then you will quickly understand how far off we are from the future and how slow technology actually moves. The writer approaches the history of technology not through the lens of innovation but from use – a use-based history of technology. This quickly reveals the pace at which humanity really adopts technology through examples like horses being more important in Nazi Germany’s advances than the V2 and the fact that we have never used as much coal as now. We are slow at technology, which is fine but we need to be aware of it. The digital divide is a real thing and it needs to be considered. Note that the digital divide is not across generational lines, yes older people cannot use TikTok, but I have seen children struggle to use a keyboard and a mouse because they are so used to touch screens. The digital divide also means that there is an exclusive group of people who do know how to use this tech and they are in high demand, to the extend that there is little incentive for workers to lend their services to the GLAM sector. Why would you work for less money in a library when you can earn a hundred times more somewhere else. Heritage sites and the wider GLAM sector can in many instance not afford to develop their own technologies mostly because they are unable to maintain them. But they also sometimes struggle to update their bought in systems because moving all their data on their collection round is too much work and effort. And in some cases the software producers are aware of this and shut down the feedback loop because they know their customers can’t leave them. To summaries saying “digital is the future” is an unproductive lie that we tell ourselves to make us feel better and trendy.

Here comes my suggestion otherwise we would be left hanging in a rather sad place. The National Trust is undoubtedly a large organisation and they already run several digital platforms which they have their own maintenance team for. What I suggest is that if people want to create cool snazzy digital interfaces they have to do this at Trust, because the Trust already have the infrastructure in place (to certain extent) to cope with the difficulties of running a digital system. E.G. https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/en/rijksstudio On individual site level however digital platforms cannot be made or maintain and the only option in my eyes is to either to keep it analogue (better for the environment) or DIY digital. By DIY digital I mean word docs and spreadsheets and softwares that are a little more accessible to a wider group of people. These option are more accessible and more maintainable but they are less sexy. When it comes to working with digital you have to know your limits and the people around you and the people who will come after you. It is not exciting but it might just solve your problem.

OHD_BLG_0043 Philosophy is easier than reality

On Monday 11th April 2022 I attended and ran a workshop at the Seaton Delaval Hall Community Research Day. It was an exceptionally interesting affair and mostly certain did not go the way I imagined. If I had to sum it up I would describe it as engaging but impractical. To say that it got deep real quick would be an understatement but the to which it went was fascinating. It was also great to just bounce ideas off people. However it felt like whenever I attempt to move the conversation to getting to more practical solutions people rather stayed in philosophical and imaginary realm or they would just explain why it would not be possible to change that.

Maybe I am too much of a designer, wanting to think of solutions instead of sticking to the status quo. Or maybe this is exactly what I should be doing, building a bridge between the imaginary realm and the real world. Maybe this is the point that Verganti talks about when he discusses ‘Interpreters’. The people in that room on Monday were my interpreters, the people I can draw on for inspiration and ideas…

If this is the case it is now my job to turn the “multi-verse” of history that we kept talking about into reality. No pressure….

OHD_BLG_0045 Leaching off Public History MA trips

Two thing I learnt while tagging along with the Public History MA trips to various heritages sites.

Chasing funding

We went to three different heritage sites of varying status and every single one of them mentioned funding many, many, many times. Like many things in the world money is the foundation of any project, endeavour, or system, without it nothing happens, even in the heritage sector where a considerable amount of the labour is free because of volunteers. The majority of funding is project based. That means you write a proposal for a project, which has target outcomes and needs to be completed in a set amount of time. Once the project is finished and you have used up all the funding you have to go look for another project and a new funding. This is often referred to as the funding cycle. The funding cycle is not necessarily good in supporting legacy long term projects. “What will happen when the funding runs out?” is constantly looming over any project and many people actually spend a lot of time writing funding bids instead of working on projects. I therefore not the greatest fan of the funding cycle but there was one person we talked to during the week that gave me a new perspective on the whole thing. They said that the funding cycle allowed them to constantly be reflecting on their practice and what they should be doing next. This is interesting to me because reflective practice has been taught to me as a new and innovative groovy thing. New systems keep on being developed in order to incorporate more reflection but in the funding cycle it has always existed, kind of… It is probably a lot easier to have this attitude when you know you are going to get the next funding anyway, which this person definitely did.

Democratisation of Space

The second thing I realised/changed my perspective on during these trips was how you can view a lot of the politics through the idea of “whose heritage is it anyway?” but somehow I realised that it might be helpful to view it within the context of space and ownership of space. This is quite common in art I guess as people often talk about who gets put in certain gallery spaces and who does not. Every group has their history which they can keep but where it is displayed is where the power truly lies. Sure you can have a history of black people in the black history archive but a far more powerful space to have the exhibition would be the British Library or National Gallery. My theory is: that when we talk about democratising heritage what we really are talking about is democratising space. How can we represent our multilayered history in our limited heritage space? I am thinking that the answer is probably something along the lines of nonpermanent exhibitions…

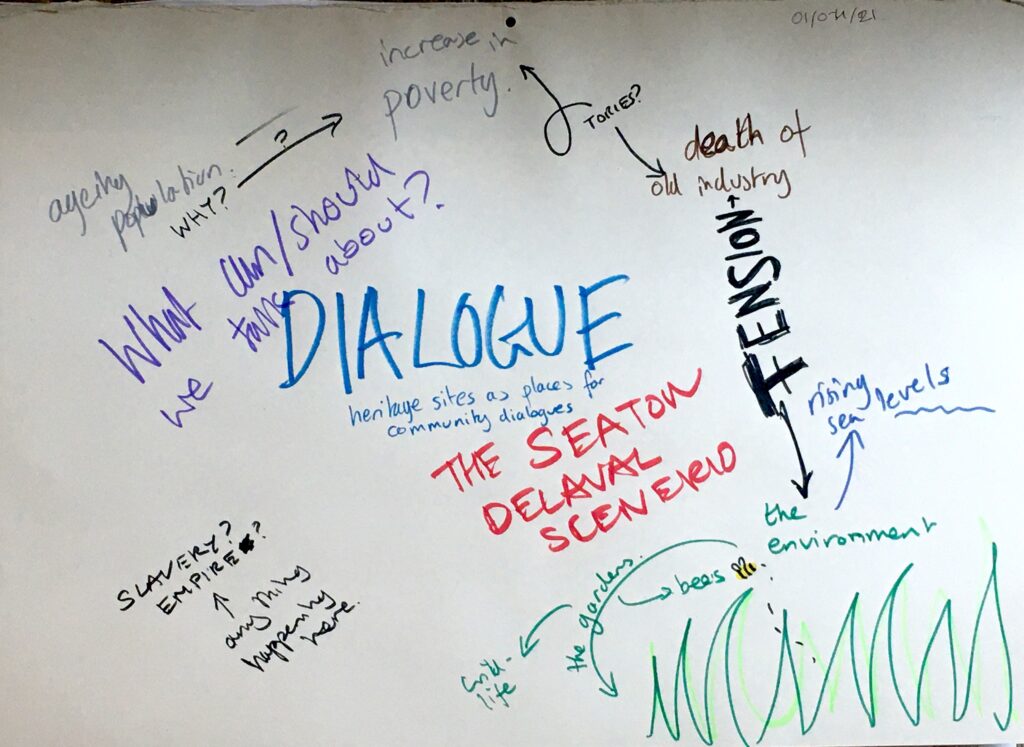

OHD_BLG_0067 Sites of Conscience

by Liv Ševčenko

“Heritage can never be outside politics – it is always embedded in changing power relations between people.“

“integrating dialogue into every stage of heritage management, from planning to preservation to interpretation, and allowing for continual evolution.”

Museums are great at showing history, but they always do this through the lens of the present. And the present has this annoying habit of constantly changing, this means that the lens used to initially set up the exhibition is probably out of date by now.

The International Coalition of Sites of Conscience fights this problem by setting up heritage sites as places for open dialogue about contemporary problems. They do this by obviously working with the community but also continuously mining their history for perspectives on problems. It’s continuous baby! And exactly what I want to do!

Also super fun idea of incorporating discussions on how to set up an exhibition into the exhibition.

Above you see my brainstorm around what dialogues we could possibly do a SDH, bu I think that other people are way more suited to think about this. However it will be a good exercise to do with people.