The archiving and reusing of oral history is often dubbed “the deep dark secret” of oral history, because a significant amount of recordings once they have enter long-term storage are not used again. Investigating this issue and trying to come up with solutions has been central to my PhD research, and so I thought it would be helpful to your endeavour if I were to take you through some of my findings.

The first thing you need to know about archiving and reusing oral history is that it is a multidimensional problem. In design this is often referred to as a “wicked problem”, a term coined by Horst Rittel and Melvin Webber in their 1973 paper titled, Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning. The term ‘wicked’ is not in reference to the ethical standing of the problems, but is used to capture the difficult nature of the issue, how it is malignant, vicious, tricky, and aggressive. The area of concern is dynamic and interconnected in ways which makes it hard to create a single perfect solution. It is for this reason some designers prefer to use “situation” and “opportunity” instead of “problem” and “solution” as a way to communicate the continual and reflective work that needs to happen when dealing with such complicated situations as the archiving and reuse of oral history recordings. So why am I telling you what a difficult issue archiving oral history is? Well because setting up an oral history programme will require the storing of recording long-term or short-term and as this “deep dark secret” of oral history is something you are guaranteed to come up against and not recognising the complexity of this wicked problem can as Rittel and Webber write could be morally objectionable.

However, you have one distinct advantage when tackling this issue of oral history archiving and reuse – you are not starting form scratch. There have been many attempts to solve the deep dark secret of oral history, some more successful than others which is excellent news as the design theorist Victor Papanek writes, “The history of progress is littered with experimental failures.”.

So to quickly summarise:

- This issue of oral history archiving and reuse is a difficult, multidimensional, and dynamic situation

- There is a long history which we can learn from

Now as I said there are many dimensions on this situation but through my research I have found some general areas which at good starting points for your consideration: technology, ethics, labour, and money. I am going to quickly explain each of these and show how they are interconnected.

I am starting with technology because this is the area which often hogs all the attention, which is not surprising, we like the technological fix, it’s sci-fi, it’s the future, it’s a bit magic. But its magic is an illusion, as Willem Schneider acknowledges in his reflection on the oral history reuse technology Project Jukebox. Technology on its own will not solve the wicked problem of oral history reuse. This is generally for two reasons:

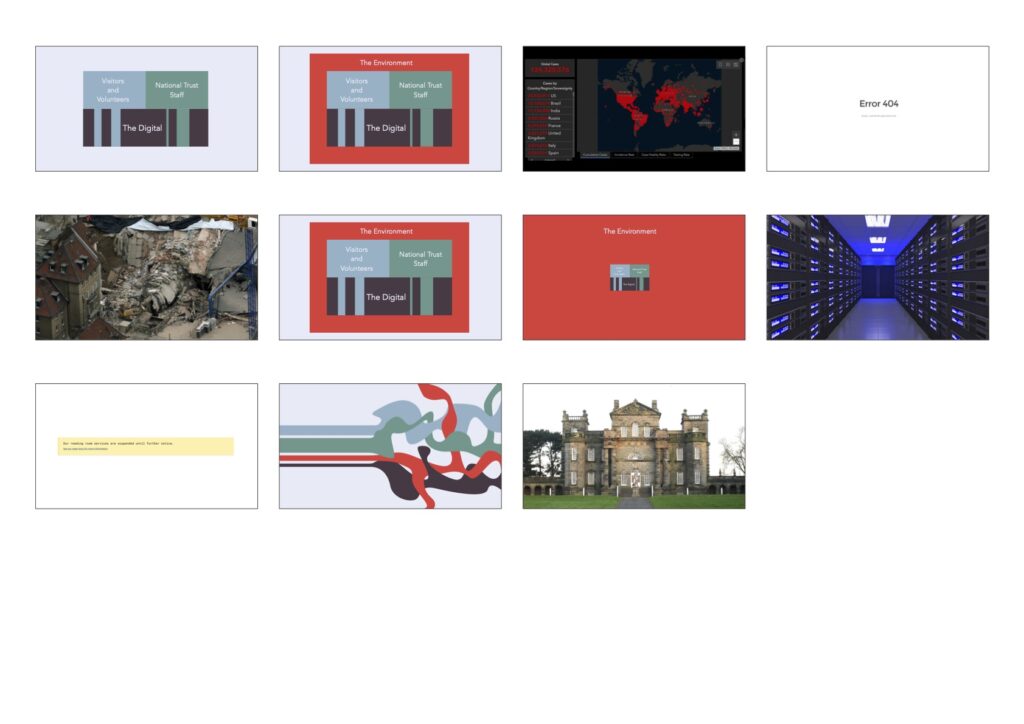

- Firstly it is constantly and rapidly evolving, and tech companies have built obsolescence into their product making technology not a particular stable area which is not helpful when you are setting up an archive or any form of long-term digital storage.

- In addition, the digital world exists as a web of interconnecting systems. Your laptop is made by one company while your software is made by another, and there is another completely different organisation running the internet. If anything happens to one of these systems it is likely to have a ripple effect across the entire networks of interconnected systems. Again this is not a stable environment for long-term storage.

The big lessons we can learn from historical failures are how technology is not the single route to solving the issue and how its unstable nature is one of the greater challenges of this endeavour.

However, technology is also where some of the most interesting opportunities lie. This oral history archive will be created in a post-AI world and therefore will be able to explore how this will affect archives. There is also an increasing awareness of the environmental effects of long-term digital storage and how this is a pressing issue in the age of data.

Next section – Ethics. I have done three different placements for my PhD and in during all of them I was trying to make archival material reusable. I spent those six months not thinking about technology but working on either copyright, data protection, or sensitivity checks. When you are working with oral histories you are dealing with people’s lives, permissions and restrictions have to be in place in order to make it available. And ethics like technology is also always changing. Copyright in the form we know it now was heavily influence by the rise of the internet in the late 20th century. The various data protections laws have only become a thing in the last ten years and definitely will be changing as attitudes change. In addition to this what language and images are deemed socially acceptable is also always changing. The constant evolution of ethics is both a practical challenge and a fantastic research opportunity as this endeavour is working on a very large scale and is a relatively a new geographic area for oral history to be deployed. It is likely setting up the ethics for this project will deliver some new insights into the ethics of oral history archiving in general.

One of my central conclusion of my PhD is how labour, specifically maintenance labour, is critical to successful innovation in this area. Both the areas of technology and ethics will require maintenance labour because they are these continually evolving areas. When we look at some historical attempts to solve this issue we see that some of the technological solutions fail because they did not account for the maintenance it would require to keep the technology. In the case of ethics evolving, one of placements during my PhD required me to do a copyright audit of a large collection. It turn out that out of 1700 recordings only 400 had the correct copyright, meaning that 1300 recordings were not reusable. This likely happened because no one had checked whether these recordings had the right copyright permissions until I came along. In both instances maintenance and the labour it takes to keep long-time storage was not considered and therefore the innovation collapsed or requires a significant amount of restoration. Restoration is only necessary when maintenance fails. In How Buildings Learn Stuart Brand quotes John Ruskin, “Take proper care of your monuments, and you will not need to restore them. Watch an old building with an anxious care, guard as best you may, and at any cost, from every influence of dilapidation.” This endeavour has the great opportunity to explore methods on how to sustain and maintain innovations, by putting labour in a central position. It can give us insights into how organisation are sustained through institutional memory and create ideas on how technology and humans can synthesise their respective abilities to create better long term storage for archival material.

Appropriately the overarching area of tension in this complex issue of oral history archiving and reuse is money. If we look at the history of technology driven solution which failed, many eventually collapsed because people were not maintaining it and people were not maintaining it because they were not getting paid. When the money runs out the work stops and it collapses. And therefore you need to know the budget and consider the long-term requirements of running and maintaining an archive. Here again is an opportunity to develop new forms of spending plans that both encourage innovation and support maintenance, something which currently is not standard practice.

So these four areas are the key starting points to the identifying opportunities to improve the situation around oral history archiving and reuse. Now it is important to note that these are just starting points and each version of the oral history archiving and reuse situation will be different to the next one. Archiving oral history recordings as an small community base project in the country side of England is a different situation to this project and therefore will likely render different opportunities. This is especially the case when you consider how oral history is or be will value within its particular setting. How we value history and historical material will influence how the material is archived and reused. There are many examples with oral history’s legacy where you can clearly see value has shape the project. Certain topics are considered more valuable than others in certain cultures. For example in Europe and the USA the holocaust and the world wars are popular topics for oral history projects. These very intense and heavy topics will bring different ethical issues than lighter topics. Some oral historian’s prefer video recordings over audio recording, another expression of value which will shape the collection. You also have differences in how oral history is valued in relation to other historical materials. Maybe someone uses a photograph in their interview or wishes to record on location, again this will change the set up of collection. All of these decisions will effect what technology might be used, what the ethic forms need to look like, what work needs to be done, where the money can come from. This project needs to understand what it values and how this might shape the project but also how these values might change and how the system will accommodate these changes in value.

The issue of oral history archiving and reuse is not a banal, tame problem. It is a wicked problem – a mess. But it is also an area of great opportunity where great innovation and insights can be discovered if we do not tame the wicked problem but instead seek to identify opportunities which can improve the situation of oral history archiving and reuse for everyone.