Tag Archives: Project

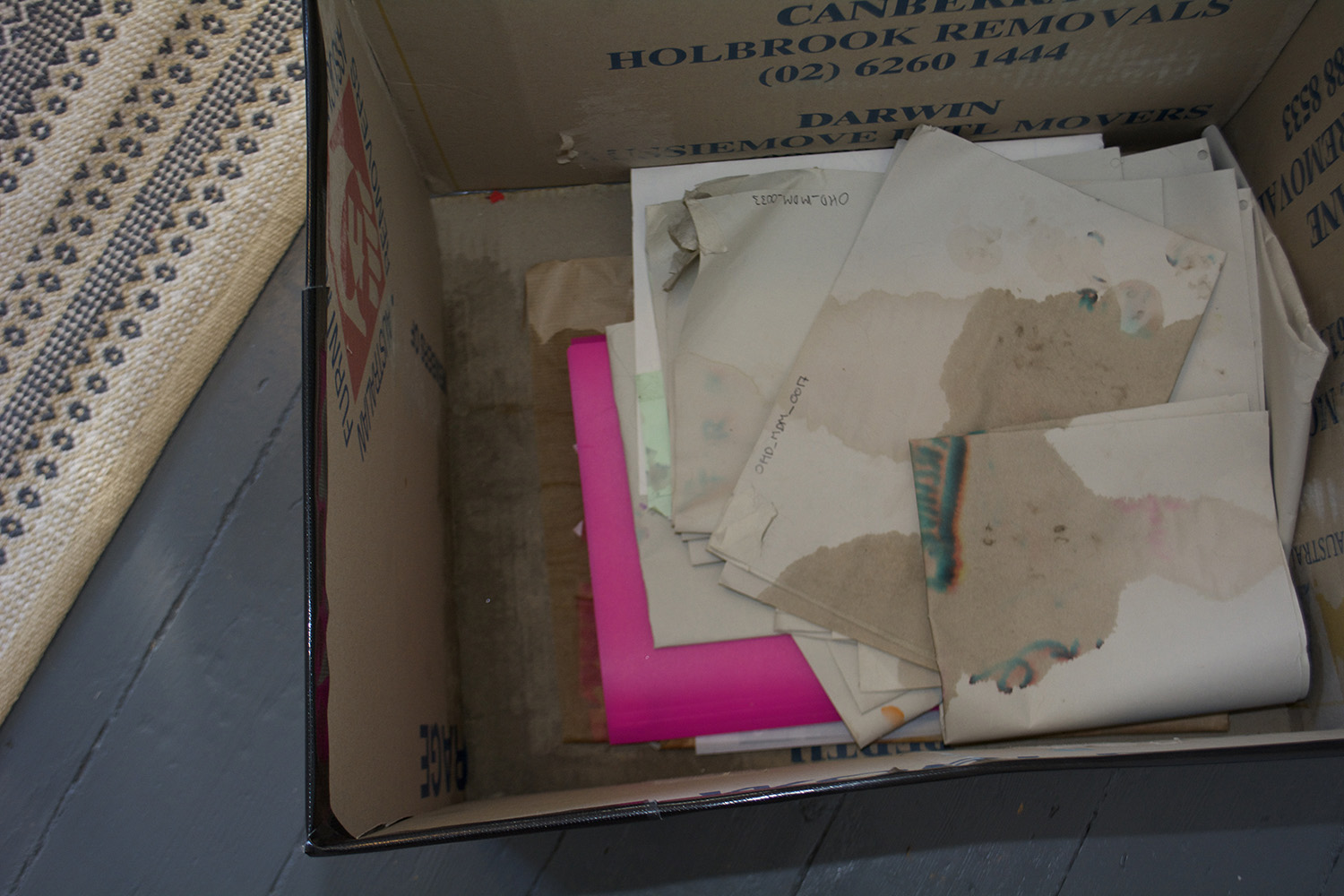

OHD_PRT_0038 Archive Box 1

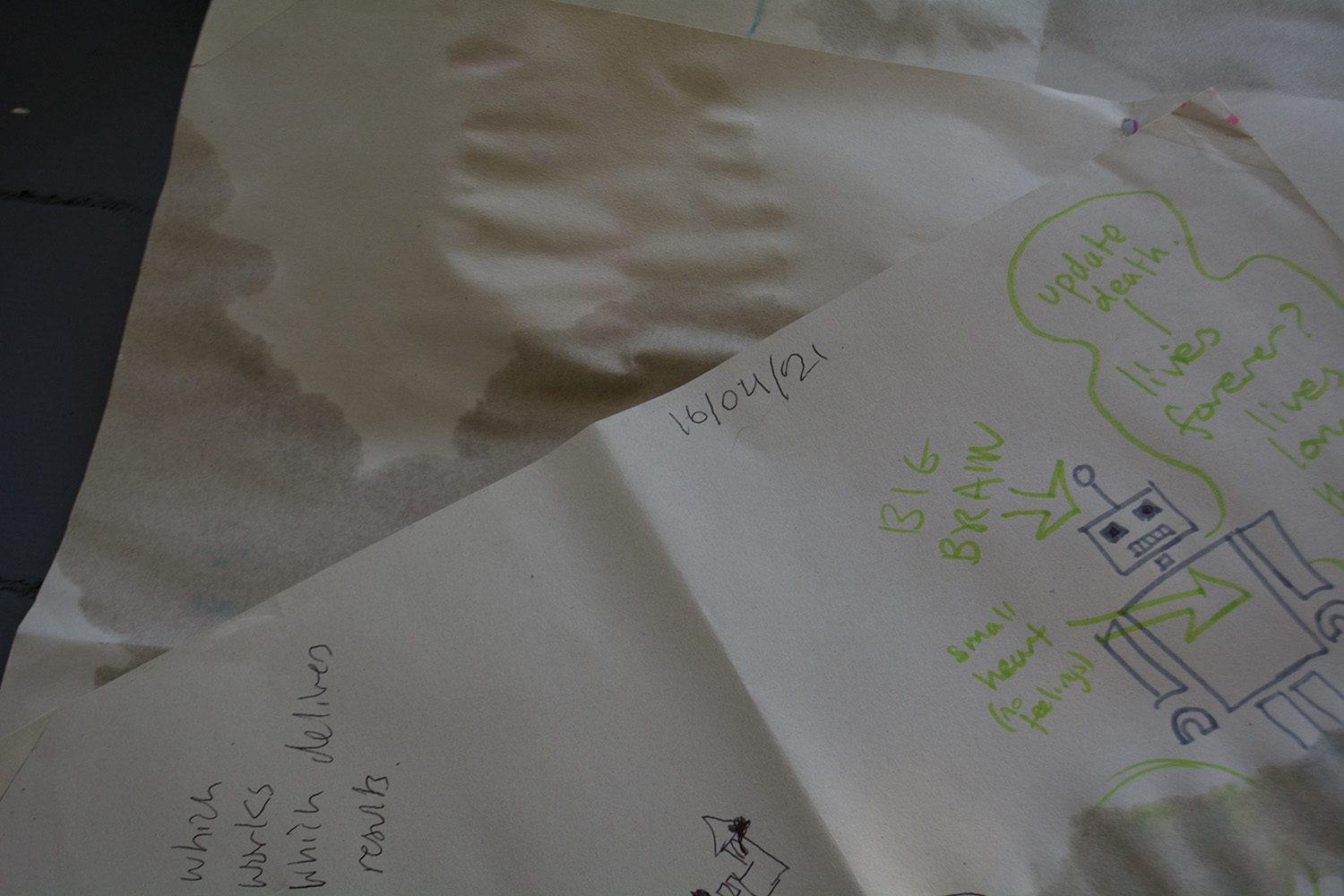

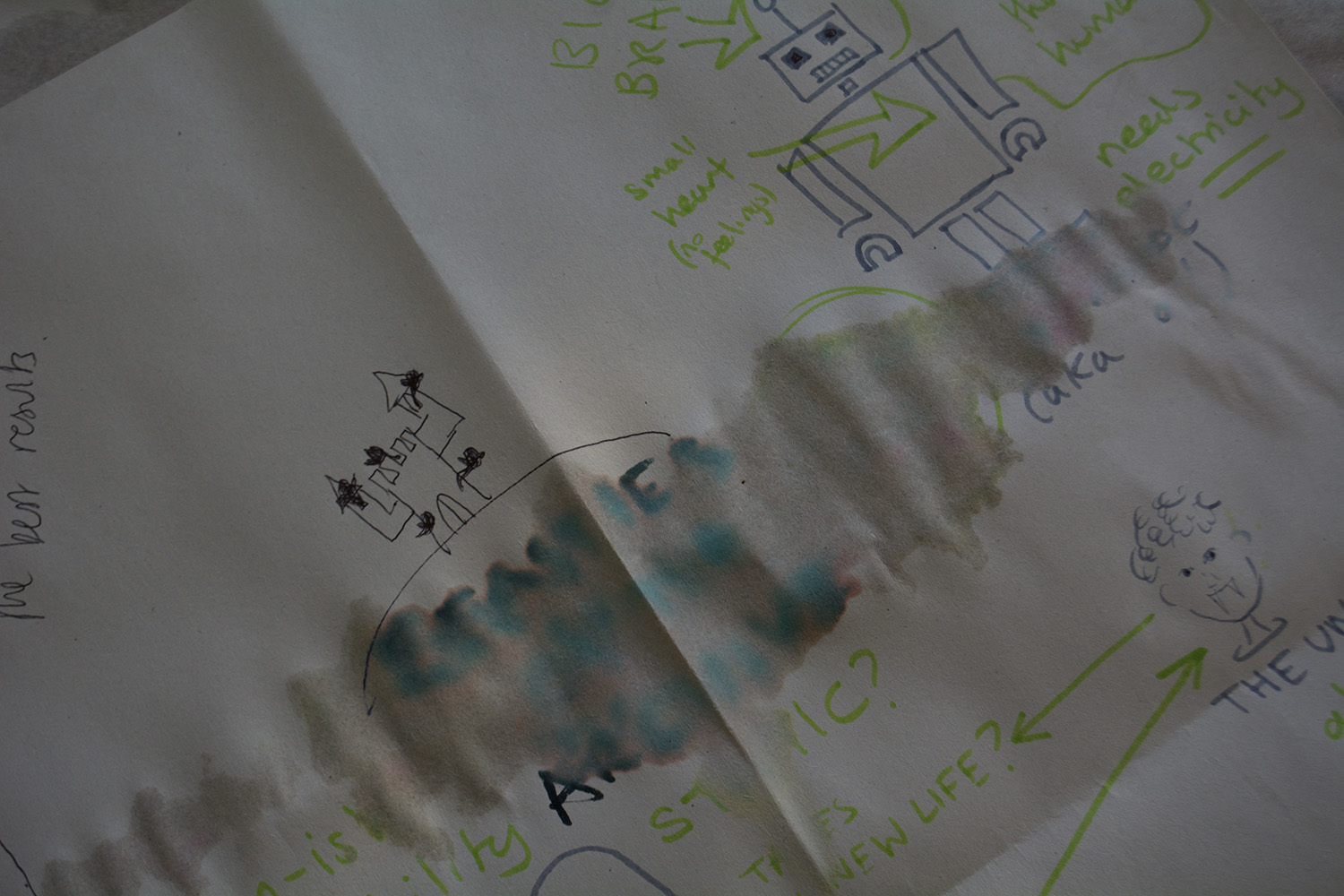

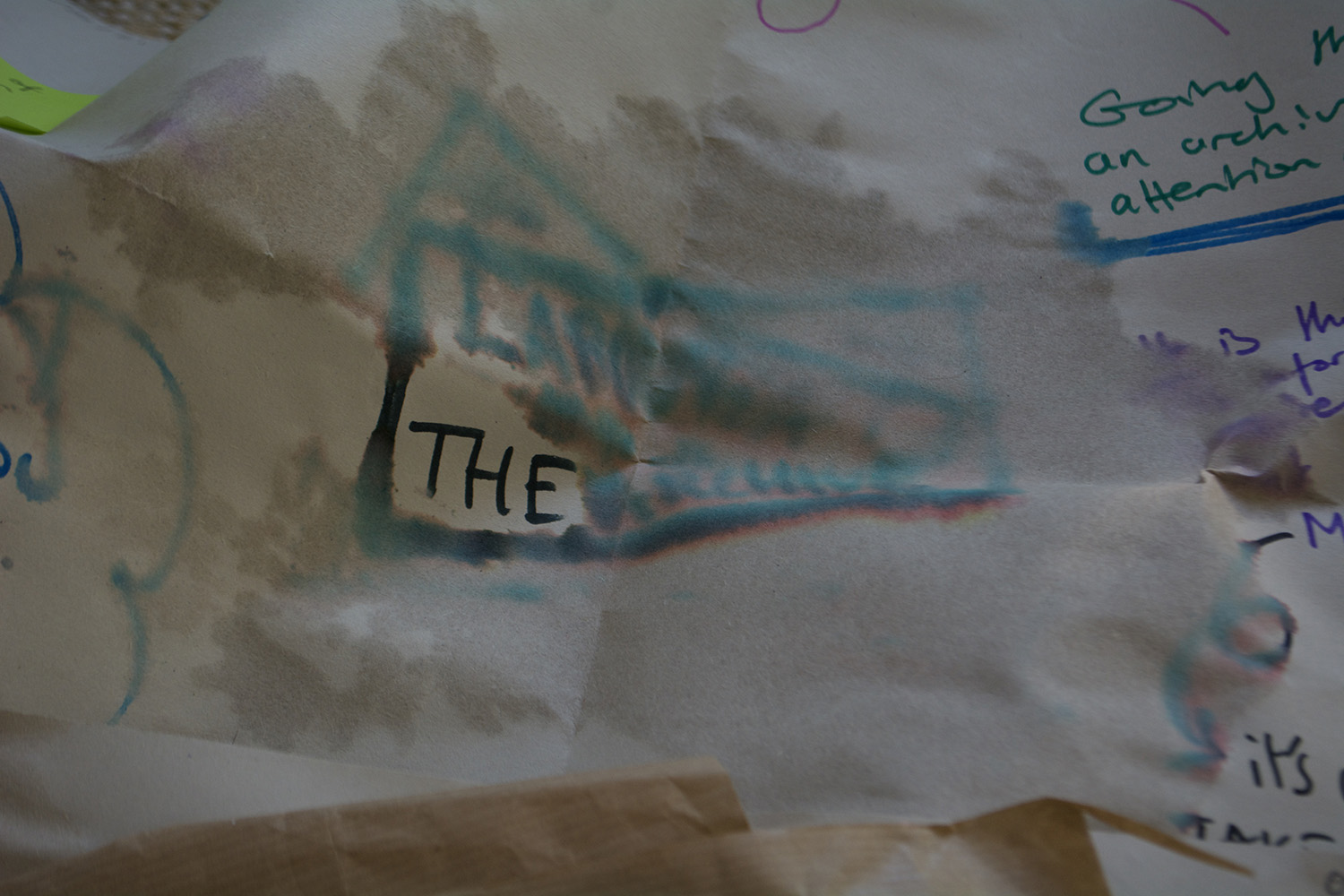

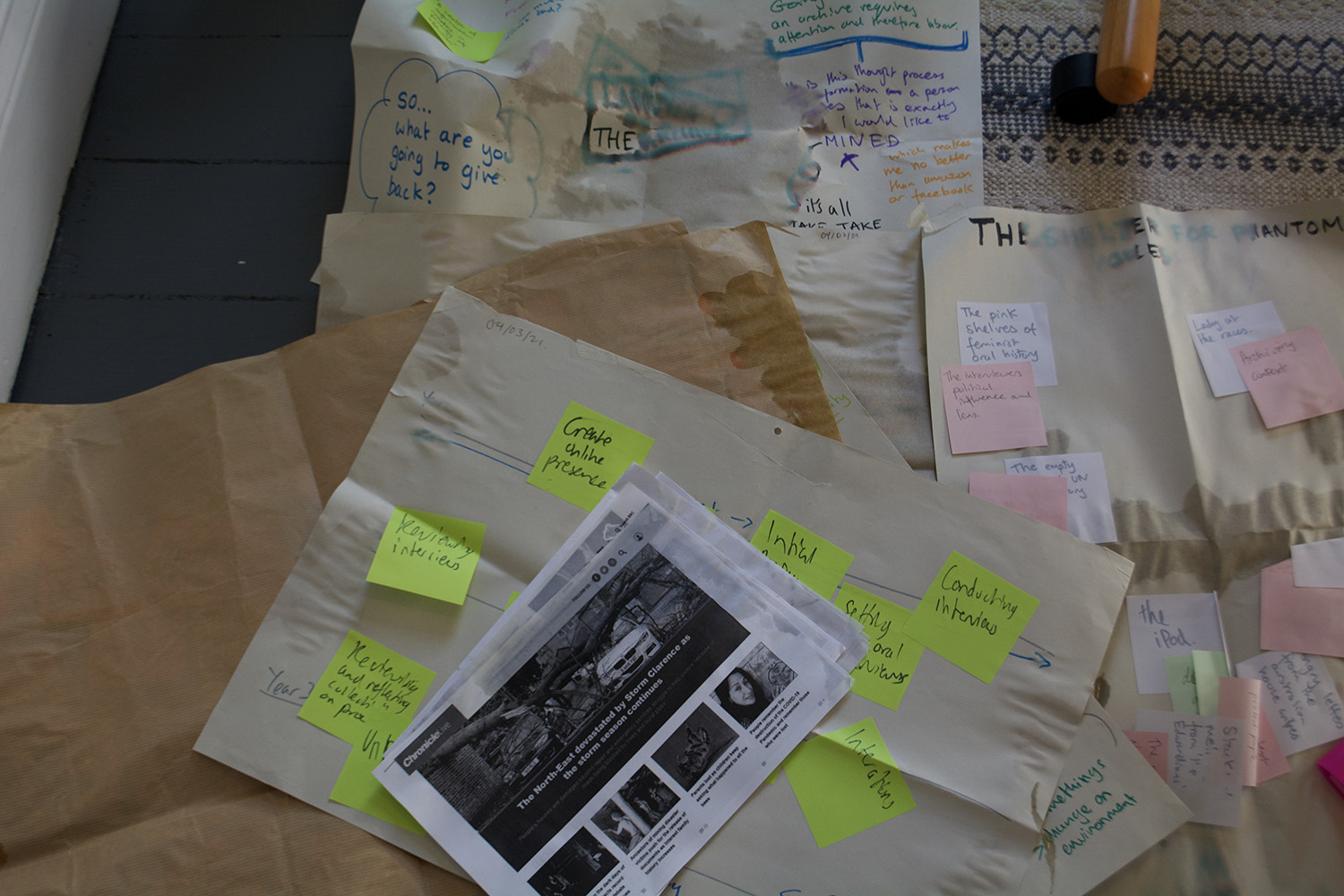

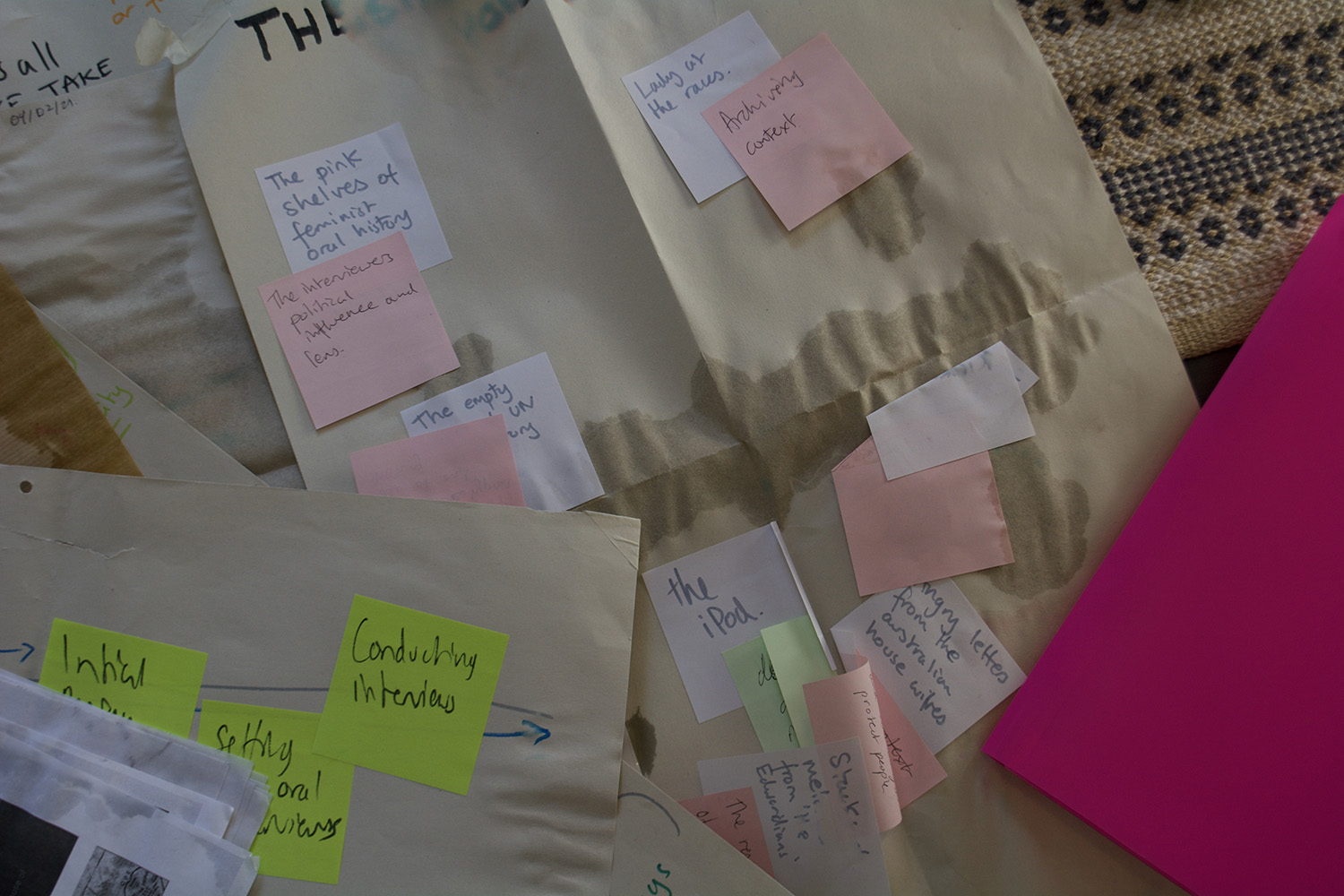

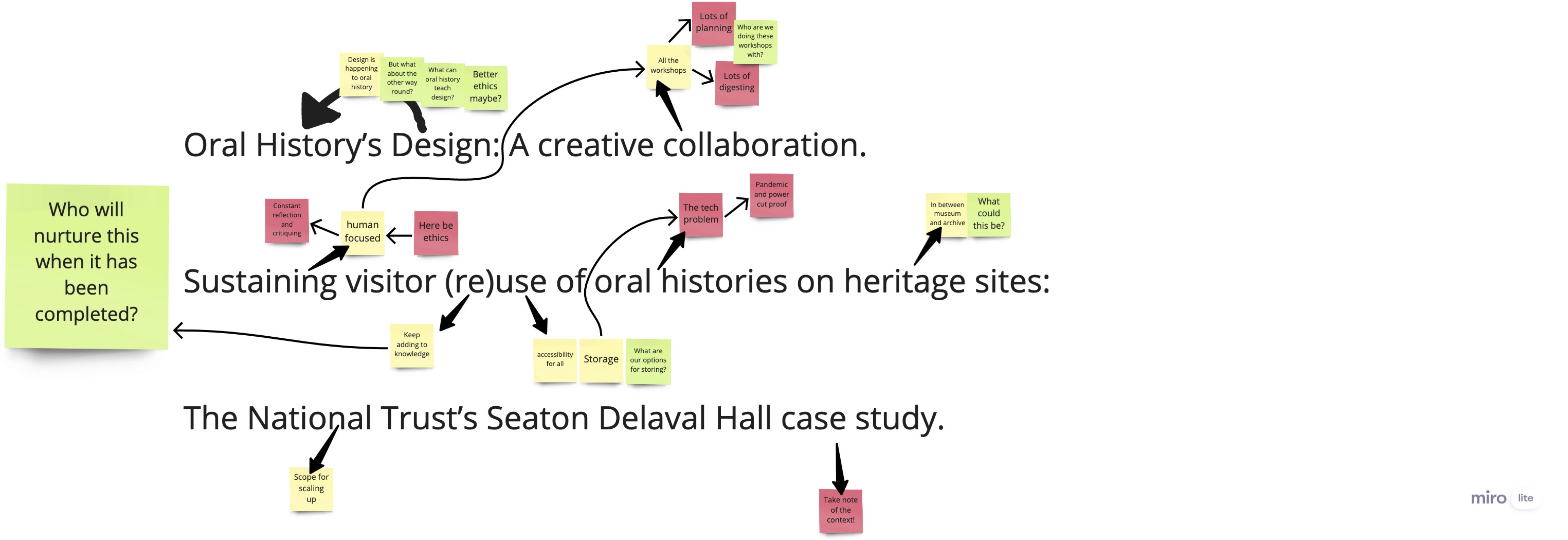

OHD_WRT_0171 CDA development update

CDA development update

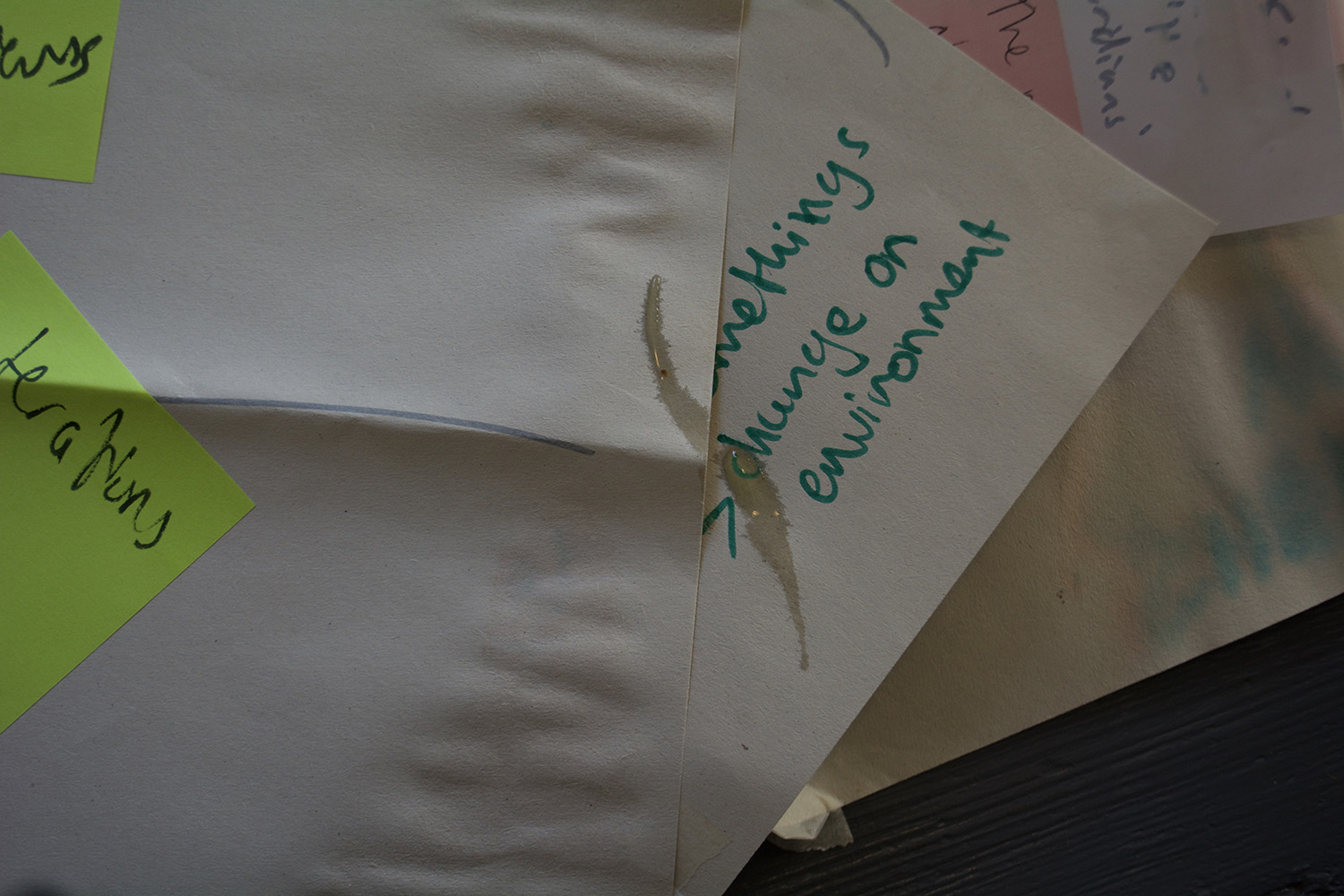

Here is a brief overview of how the PhD has changed since the project proposal split it into three sections. The first considers the significant changes that have occur globally in the last two years. The second discusses the change in the framing of the situation the PhD is addressing, reusing oral history recordings on heritage sites. And the third looks at the changes in design methodology and theory due to the environment I am designing in and for.

SECTION ONE: HISTORY HAPPENED

Since the writing of project proposal, the world experience significant changes including, the COVID-19 pandemic, further development in the conversation around the Britain’s colonial past, and a constant wave of climate disasters. The Trust did not escape the effects of these changes, having to furlough and make significant cuts to staff during the 2020 lockdown, publishing the report on sites with connections to the British Empire, including Seaton Delaval Hall, and wider actions for the Trust to achieve carbon net neutrality. In addition, the COVID-19 lockdowns also highlighted the public’s need for access to open spaces and nature, while storms, like Storm Arwen, highlighted the threat the climate crisis is to the Trust running open natural spaces. It is because of the changes in the Trust this project has also evolved and the project is unfolding in a very different environment than when it was originally proposed. The project therefore has to think about the environment impact of the designs it is developing and think about how the design might fit in the (post-)COVID structure of the Trust. In the original proposal the project was already thinking about a 360˚ interpretation of the hall but now this seems more important than ever.

It is also interesting to note, while it is true that National Trust sites are to a certain extend run autonomously, they do not operate in a vacuum. National Trust sites function inside the wider structure of the Trust, an extensively complicated network of rules, regulations, and resources. I believe the influence this structure has on the project was slightly underestimated at the time of writing the project proposal. For example, the Trust’s digital infrastructure which has strict rules and regulations about digital storage has become quite the barrier, the extent of which had not really been realised before the start of the project.

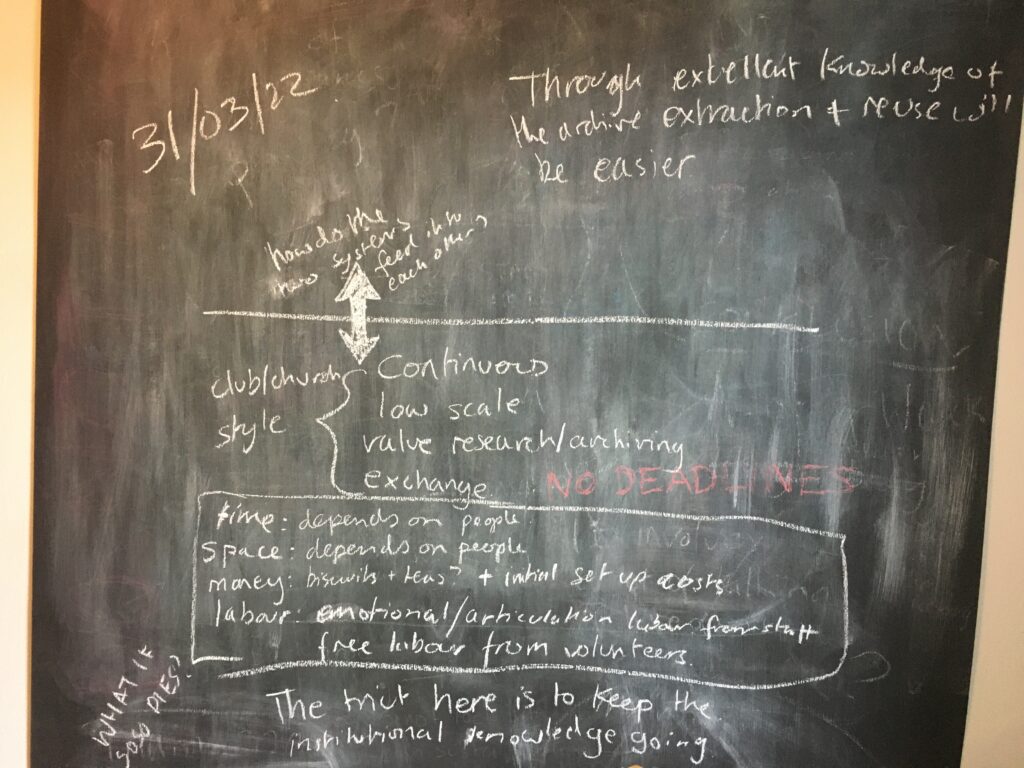

SECTION TWO: BUILDING THE FOUNDATIONS

In the summary of the project proposal it is written that “the PhD would generate, in partnership, new knowledge in understanding and addressing visitors’ active engagement in interpreting the past through reusing a National Trust oral history archive.” The big assumption made here was that “a National Trust oral history archive” was either already in existence or would have been easy to set up. What the last two years have revealed is that this part of the task is easier said than done and the struggle in setting up oral history archives that allow reuse is not unique to the National Trust. After I did a deep dive into the many attempts to make oral history recording more reuse friendly through digital tools, it became clear something more fundamental was not being addressed. Most frequently the downfall of these digital solutions was the projects coming to the end of their funding, meaning there was no money to support the maintenance needed to keep the technology running, which eventually resulted in their deterioration.

If we return to part of the original title of the PhD, “sustaining visitor (re)use”, the project initial was about building a system to allow visitor interpretation of oral history recordings. However, two years down the line “sustaining visitor (re)use” seems only achievable if at first, we create a solid foundation on which a system for visitor interpretation can be build and maintained. In order to create these foundations, there needs to be a focus on maintenance and the resources needed to support the storage of oral history recordings, which is something that has been missing from other endeavours into oral history recordings accessible. The resources needed will obviously include labour and money but also energy. As the large carbon footprint of internet servers and the storing of digital files is being realised. This project also needs to think about how we are able to store oral history recordings in the most energy efficient way possible, while still ensuring they are accessible and reusable to a wide range of people. This is especially important with the Trust’s aims for carbon neutrality.

SECTION THREE: CHANGE IN METHODOLOGY

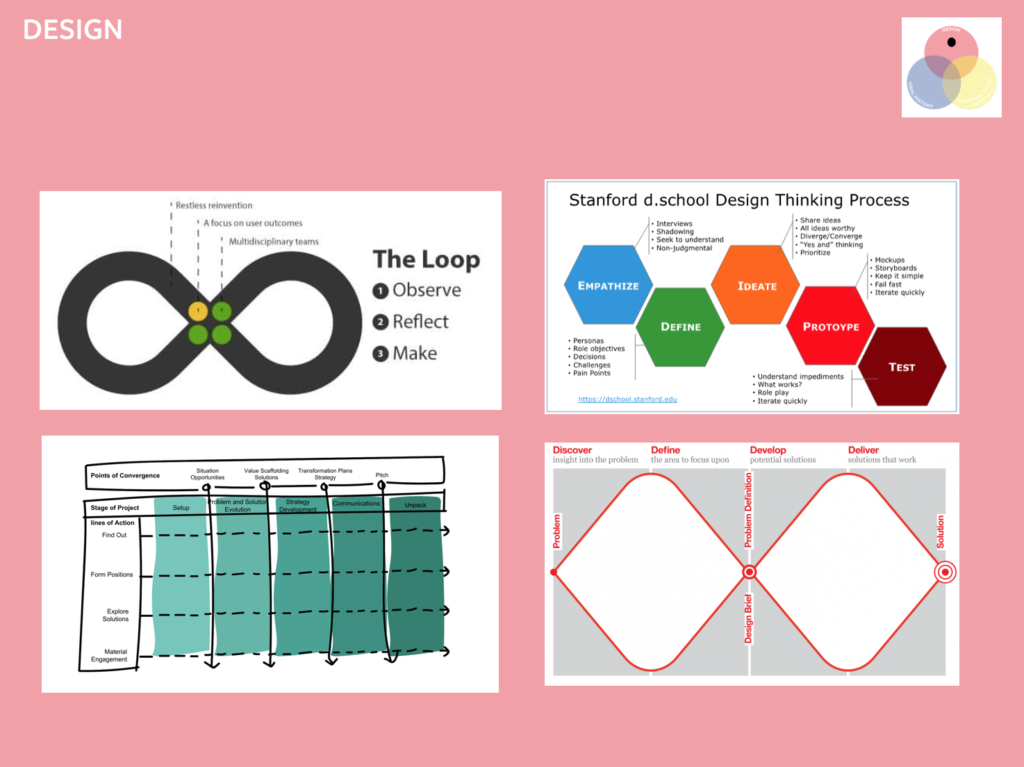

Back in the original proposal Roberto Verganti’s idea of a technological epiphany is mentioned as a possible route for the PhD. However as written in the first section the Trust’s digital infrastructure is slightly rigid and is likely to not accommodate any radical technological innovation, meaning that a technological epiphany is unlikely. What we can still take from Verganti is his ideas around a change in meaning. What does it mean to do oral history on heritage sites? And how does oral history benefit heritage sites in the long term, beyond the idea of volunteer and visitor engagement within a set project timeline? Alongside Verganti’s idea of a change in meaning I have taken on design theory from Cameron Tonkinwise about ‘design for transitions’, which involves thinking about the life of designs outside of the project timeline and Victor Papenek’s six elements of function that lead to a successful design: use, method, need, aesthetic, telesis, association.

With the project design practice there has been another change. Instead of following a step-by-step process of researching, developing a prototype, testing and iteration. I have opted to use ‘infrastructuring’; researching and mapping the existing structure of an institution or system to better understand and communicate where any possible design solutions might fit. And ‘design fiction’ or scenario building as a low-risk method to harvest feedback on possible designs instead of the high-risk method of live testing and iteration. Design fiction/scenario building also seems to be an excellent way to communicate across disciplines.

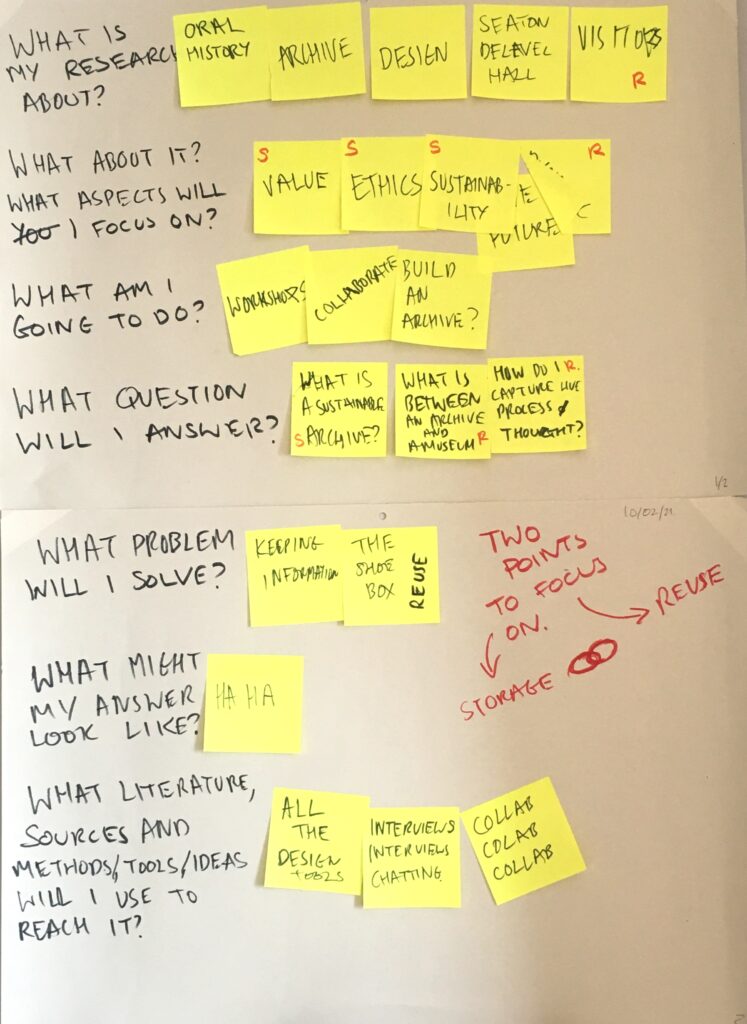

OHD_SSH_0165 Proposal Dissected

OHD_SSH_0164 Question Dissected

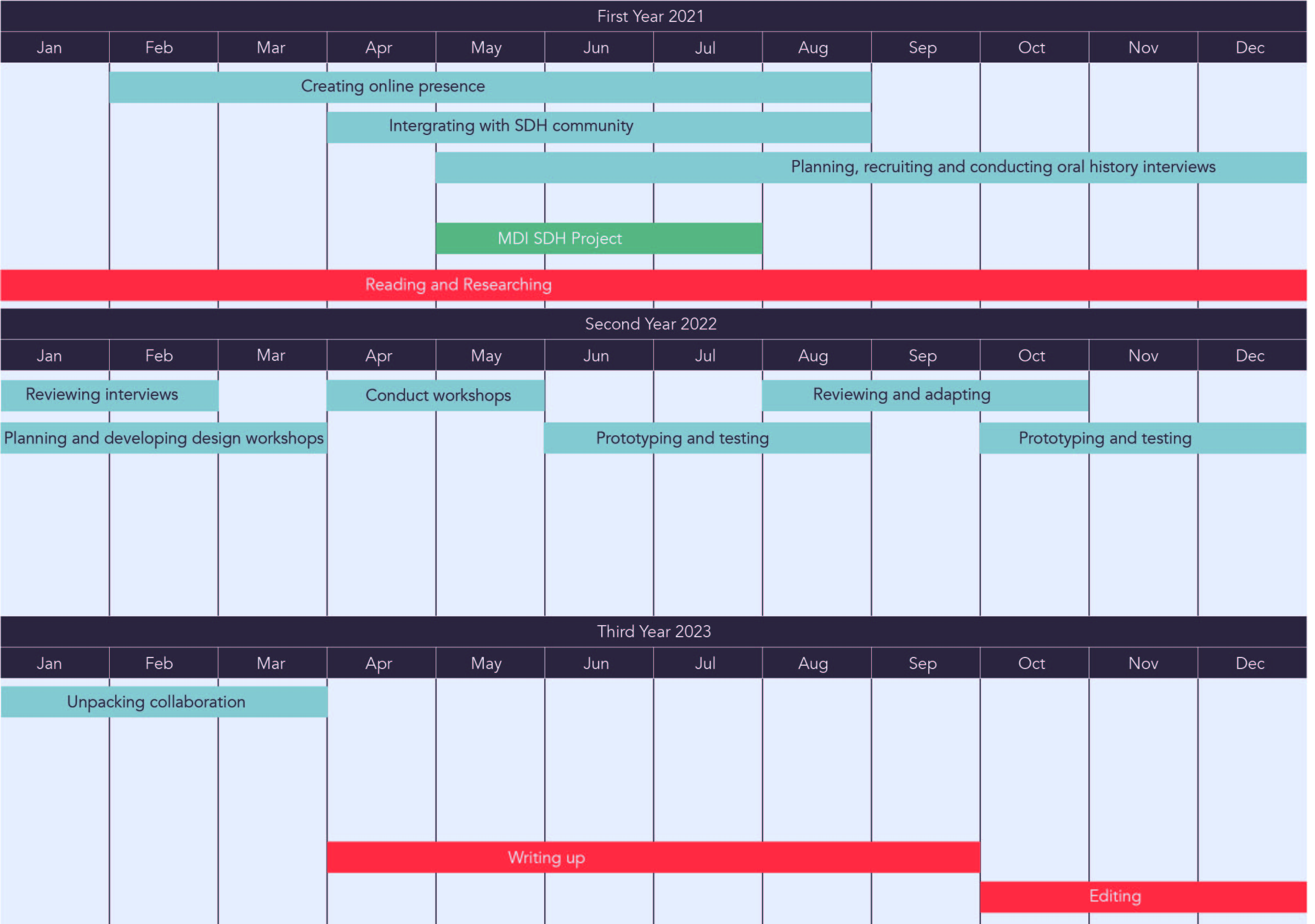

OHD_WRT_0163 Project Plan

Project Title

Oral History’s Design: A creative collaboration. Sustaining visitor (re)use of oral histories on heritage sites: The National Trust’s Seaton Delaval Hall case study.

Detail of Project Plan (Including key milestones)

First Year

Aims

- To seek how this project will create new knowledge in all fields; heritage, design and oral history

- To integrate into the Seaton Delaval Hall (SDH) community

- To create an awareness of the project both in and outside of the SDH community

- To have a collection of oral history interview recordings by the end of the year

- To gather initial ideas on the design of the archiving system

Actions

- Read and research

- Attend SDH staff meetings

- Talk to the volunteers

- Set up online presence

- Record pilot interviews

- Plan, set up and record interviews

- Conduct initial design workshops

Second year

Aims

- To create a bank of archiving system ideas

- To develop and prototype the ideas into real systems

Actions

- Review the recorded oral history interviews

- Use the recorded interviews in workshops with various parties to generate ideas for an archiving system

- Prototype, test and review workshop outputs

- Iterate as appropriate

Third year

Aims

- To unpack the collaborative process

- To write up findings

Actions

- Review and and reflect on collaborative process

- Writing and editing

Note that throughout the project there will be continuous project updates and feedback opportunities with the community around SDH.

Project impact on well being and mitigating risk

Due to the collaborative nature of this CDA there are many players from different fields that are involved in the various stages of the project. As the research student for this project I am acting as ‘project manager’ for this CDA. This role requires me to take up some organisational work alongside my research. However, I believe that with realistic goals, well delegated time, and clear communication with my supervisors, I will be in a strong position to complete my CDA to its fullest potential. In addition to this, I have also been made aware of the resources that both universities offer to support students’ well being.

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval will be sought when method and sampling strategies are finalised.

Summary of proposed project (500 words)

Oral history’s ‘deep dark secret’ is that its focus on collecting histories has inadvertently led to a neglect of the archives and the option to reuse existing oral histories in historical interpretation. This project draws on new developments in oral history reuse theory and practice, in combination with design, to explore how heritage site visitors can become active curators and historians. In doing so, this project will build an on-site oral history archive, which will continuously collect new content from visitors. The project will consider how, in turn, new data can be generated to shape future collecting. The CDA would propagate new knowledge in understanding and addressing visitors’ active engagement in interpreting the past through reusing a National Trust oral history archive. The archive in question is situated at the National Trust property Seaton Delaval Hall (SDH) which is the case study for this project.

The hall is the ideal location for this case study as it is part of a local community whose history is deeply connected to the hall and vice versa. The volunteers and visitors will play a key role throughout the project. They will not only be the source of the oral histories, but will also help inform the design process for the archiving system. Along with the staff at SDH; the Oral History Unit at Newcastle University; Multidisciplinary Innovation Masters students at Northumbria University; and any other interested parties, the volunteers and visitors will collaborate to create and develop an archiving system that is tailored to their needs as a community. The project aims to document and review this multidisciplinary collaboration, investigating the opportunities and challenges that are uncovered in the process. There will be a focus on what each field can learn from the other and how this might inform future collaborations of the same nature. Simultaneously the project will develop a tool kit for heritage sites who are seeking to work in partnership with volunteers and visitors.

The overall aim of working within the hall’s community is to make a sustainable system. This sustainability will work on multiple levels. Firstly, the system has to be sustainable in order to adapt to and accommodate the new stories that are constantly being added. Secondly, it has to be structured in a way that is straightforward for the National Trust staff to use and manage for many years to come. And lastly, and most importantly, the system should aim to be aware of current and future difficulties that could arise in from the world’s ever-growing and complicated digital-ecosystem. By having the project deeply embedded into the culture of SDH from the start, the archiving system can grow together with the community, hopefully opening the door to the possibility of solving oral history’s ‘deep dark secret’.

Extra documents

OHD_GRP_0162 Project Timetable

OHD_MDM_0028 Answer to questions about project

OHD_PRS_0124 Presentation/Interview

Below is the presentation I had to do in order to be chosen as the student to complete this PhD. The interview took place on Feb 18th 2020 and the question I had to answer was, “What are the key challenges and opportunities [in this PhD] and how will you address them?”

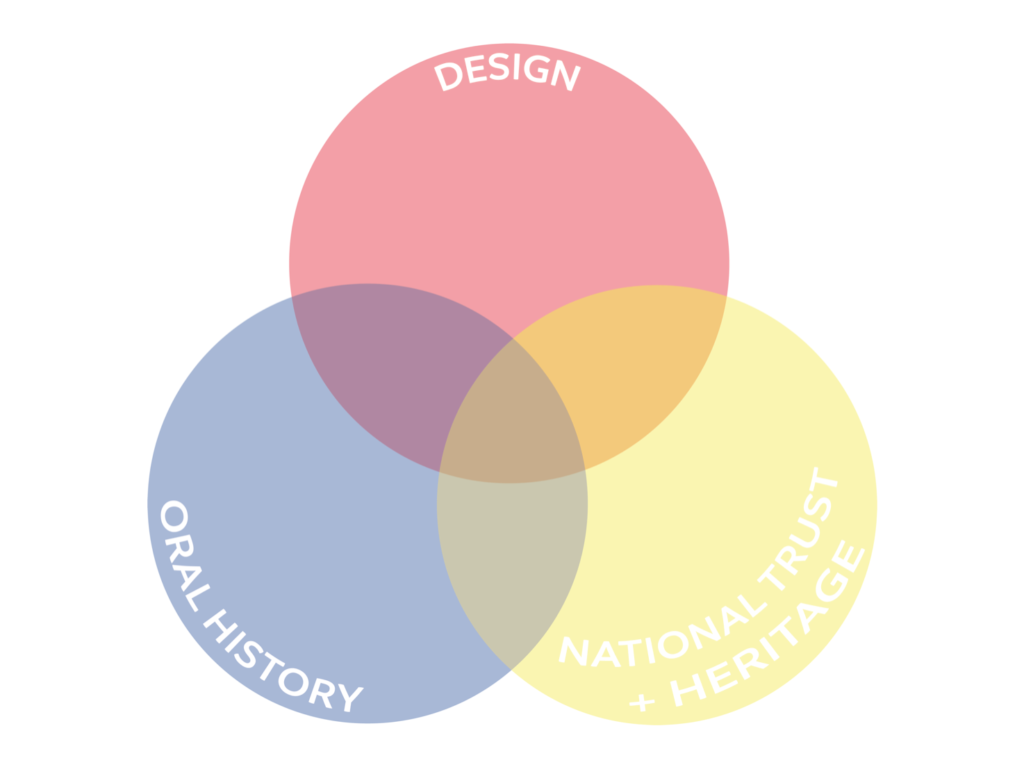

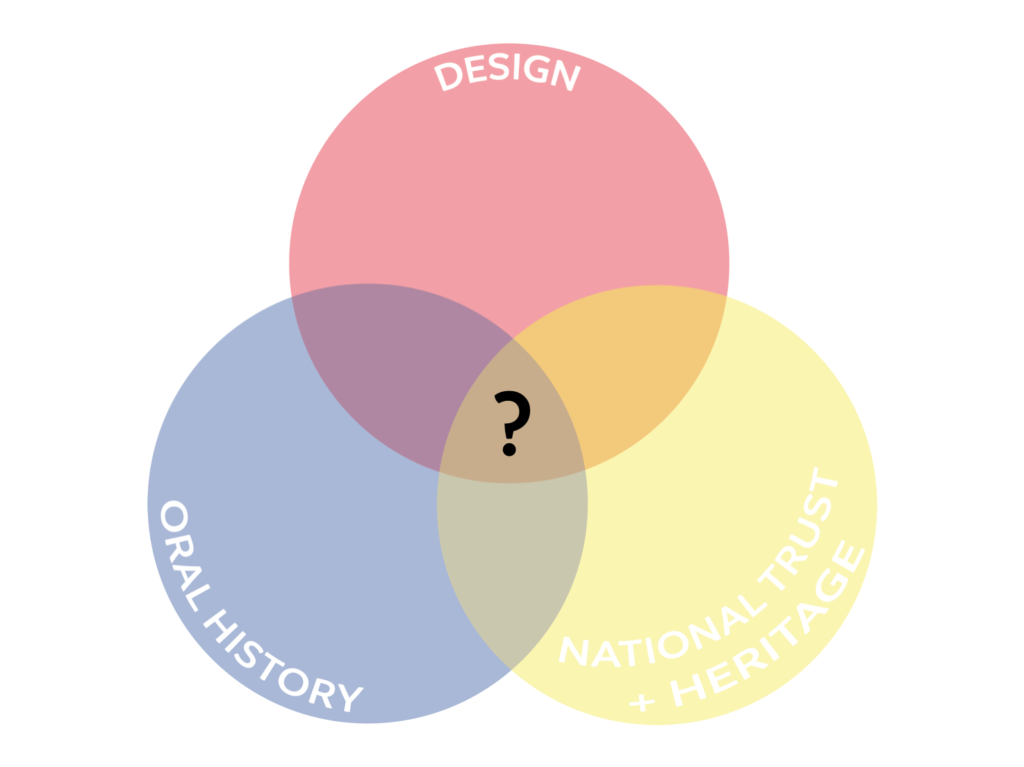

SLIDE ONE

I have set this presentation up as a Venn diagram of three main parties of this CDA: National Trust and the heritage sector, Oral history and Design. In order to answer your question, I will navigate through the various sections of the Venn diagram identifying opportunities, challenges and how will address them.

SLIDE TWO

I think the first opportunity lies with the National Trust property Seaton Delaval Hall. If you observe the setting and history of the Hall you will find it to be the appropriate setting for this CDA. Firstly, the Hall is in the middle of a wide and rich community. Over hundreds of years the Hall and its inhabitants have contributed to this community and return the community has also given back with the most recent example being the money that was raise to help the National Trust take over the property. Secondly, it is a relatively young National Trust property. By that I mean that it has only been acquired by the National Trust in the last 11 years, meaning that until very recently; stories, memories and histories were being made at the Hall. Seaton Delaval Hall is therefore a perfect candidate for any oral history project, however a recent collaboration between the National Trust and MA in Multidisciplinary Innovation at Northumbria University makes the Hall the perfect location for this CDA.

SLIDE THREE

In May 2019 as part of the Rising Stars Project the National Trust came to Northumbria University with hope to collaborate in setting up a new oral history project. I was part of the team on the Multidisciplinary Innovation MA that was given the challenge of creating a new, an innovative method for collecting, archiving and displaying oral history. We started off by investigating methods of collecting group memories, as at first we found the National Trust’s current prescribed method of collecting oral history too formulaic. We concluded that due to the aforementioned setting of the Hall there should be a focus on reengaging the local community through this oral history programme. So we wanted to create a more participatory type of oral history that reveal a bigger picture of the Hall and created a sense of collective ownership of these histories. Instead of the “rather odd social arrangement” of the one-to-one interview, as Smith describes it in Beyond Individual / Collective Memory: Women’s Transactive Memories of Food, Family and Conflict, the team wanted to lay the power of the narrative with the participants instead of the interviewer. What we wanted to avoid is what the historian Lynn Abrams experienced while working on a project about women’s life experience in the 1950s and 60s. During that project she found that her position as an expert in women’s and gender history and implied feminist meant that her participants adapted their story to fit the wider feminist narrative. However, as our project progressed and the team dove further into oral history theory we started to understand the importance of individual interviews. Especially because during the testing of our group interviews we found that some people were less comfortable with the group setting and therefore would contribute less.

SLIDE FOUR

So, after three months of research, designing, testing, refining and testing again we developed two new group-interview methods alongside an incorporated individual interview. We also created several ways to display oral histories around the property, and potential new methods of archiving oral histories. Despite the high level of outputs the project only really scratched the surface, however it gave the opportunity for this CDA to exist in the first place. I view this project as the launchpad for this CDA. What it did was start an exploration into collective ownership and the role of community within the context of oral history at Seaton Delaval Hall and it brought together the various parties sitting here today. But most importantly it revealed that it would require more time and effort for it to be successful. This is especially the case with archiving, which was purposefully left open ended by the team, because as we producing all the previously mention outputs we discovered that oral history archiving is a very difficult problem.

SLIDE FIVE

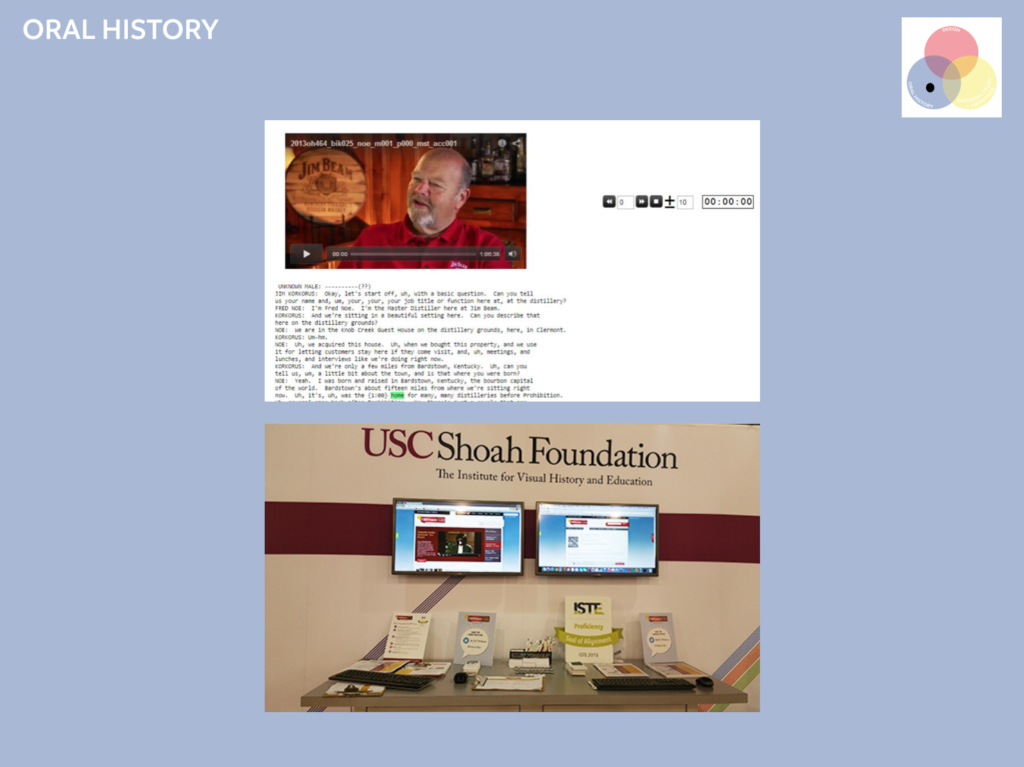

Micheal Frisch discusses difficult problem this extensively in his paper ‘Three Dimensions and More’. He describes oral history archives as a shoebox of unwatched family videos and outlines various paradoxes that occurs in oral history archives. One of the paradoxes, the Paradox of Orality, refers to the inappropriateness of the reliance on transcripts in the context of oral history. Many oral historians, including Alessandro Portelli, agree that using transcripts in archiving reduces and distorts what was originally communicated by the interviewee. Although there are many archives that rely on transcripts, there are also archiving systems being developed that tackle this exact issue. Certain systems are already engaging with this paradox by using various forms of technology. Such as the Shoah Visual History Foundation, set up by the film director Steven Spielberg, where video testimonies of holocaust survivors are indexed, timestamped in English and can be navigated along multiple pathways. Another example is Oral History Metadata Sychronizer (OHMS) created at the Louie B. Nunn Center for Oral History at the University of Kentucky Libraries, which can be navigated by searching any word and it will jump to the exact moment that person is talking about the searched word (Boyd). I imagine throughout the CDA these systems, including the more analogue archives need to be explored further in order to uncover the opportunities for innovation. What we are specifically looking for is the opportunity to create a system that is not driven by technological advancements, but by a desire to change the culture of how we use archives.

SLIDE SIX

Currently, we use all types for archives in a static way, which is the opposite to how we treat history. Not only are we constantly making new history through the passage of time, our attitudes towards history constantly changes. For example the global discussion surrounding artefacts in the British Museum or even attitudes towards mining. Recently I worked with the arts and education charity Hand Of at the Durham Miners Hall with children from the local area. Working with these children you see that they view mining through a completely different lens to the generation that came before. While you and I might associate mining with the miners’ strike and the deindustrialisation of the UK, these children view mining as something from the pass, something important to the previous communities but ultimately something unsustainable and bad for the environment.

The static nature of the archives is in complete contradiction to how people experience history. I believe this CDA is looking for is a more sustainable and dynamic preservation of stories. A system that taps into the ever changing zeitgeist reflected in its visitors instead of keeping everything frozen in time.

Well the CDA is called the ‘Oral history Design’. In my eyes I see design the provider of tools for exploration, with Seaton Delaval Hall providing the test subjects. This CDA would not be possible if it was not for the resources that the National Trust has to offer. Those resources being the visitors, the volunteers, those who provide the histories and the team working at Seaton Delaval. I believe that in order to create a system that is truly sustainable it needs to be tested at every point of the process and the collaboration with the National Trust gives us that opportunity.

SLIDE NINE

The challenge however is finding the appropriate design tools. Design intervention and the use of design thinking tools can deliver high rewards but it can also cause considerable damage if not use responsibly. Not only do I expect to do more research into design methods on top of the ones I am already familiar with. I also expect to constantly be reviewing, adapting and modifying the tools and design process as project progresses. This is something that is highly encouraged by many people in the field of including the Kelley brothers, from IDEO, who openly invite people to adapt their methods and Natascha Jen from Pentagram, who argues that design thinking is more of a mindset, not a diagram or tool. Within this CDA this might evolved into regular reflection on the process both from myself as the student and from the other parties involved. All of this is especially important because the collaboration between design and oral history is a relatively new and unexplored territory.

SLIDE TEN

This unexplored territory, however gives the CDA opportunity to explore something in addition to the creation of a new archiving system; the methodology behind cross-disciplinary work within the academy. Cross-disciplinary work is nebulous and struggles to be categorised within the academic system. As I found throughout my MA there is a lot literature that talks about interdisciplinary, transdisciplinary, multidisciplinary, cross-disciplinary work. These papers, books and articles talk about bringing various parties together in order to solve a problem but it is nearly always in the context of business or social enterprise. The CDA will therefore offer us the opportunity to research and experience multidisciplinary or cross-disciplinary work within the context of a university.

However, cross-disciplinary, transdisciplinary, interdisciplinary, multidisciplinary work, whatever you would like to name it, does come with its fair share of challenges. I am familiar with this as during my MA I had to work in an 18-strong team of people from a diverse range of ages, ethnicities, nationalities and socio-economic backgrounds and different fields of work. Throughout the year it was clear that one of our biggest barriers was communicating across these differences. It often felt like I was speaking a completely different language, which sometimes was the case, as certain ambiguous words were perceived differently depending on the person’s background. I predict this to happen throughout the CDA, not only across the design and oral history but also with the National Trust and any additional parties that might be involved.

SLIDE ELEVEN

It is essential that we have as many of these cross-disciplinary conversations as possible. Roberto Verganti, in his book Design-driven Innovation, refers to these types of cross-disciplinary conversations as a ‘design discourse’ – experts from different backgrounds exchanging information. Verganti finds this to be essential in design-driven innovation, an innovation strategy that pursues change through a reinvention of the meaning of a product or system instead of relying of technology. Which is exactly what this CDA is looking for.

This design discourse needs to be managed and organised efficiently, which I feel confident I am capable of doing due to working in teams throughout my professional and academic work. Especially thanks to my MA and my work with Hand Of and teaching for the early English programme Such Fun! I know the importance of clear communication and disciplined organisation. I imagine that I as the student of this CDA, I will have to take a project manager-esque role in order to float between the different disciplines, communicating progress and finally managing expectations.

SLIDE TWELVE

And that really is the crux of it all, managing expectations, because you cannot guarantee anything. For all we know the answer to design oral history archives is – don’t, National Trust’s prescribed archiving method of electronic cascading files does the job perfectly well. For now this CDA is exploring the unknown, but that is what I like about it. I spent three years in a Goldsmiths art studio exploring the unknown, then I did an MA do to more targeted exploration of the unknown and now I have a narrow it down again in applying for this CDA. Exploring the unknown is full of opportunities and challenges, but you have to do it in order to find them and I very much like to do it.

The feedback a got on my presentation was good, however I did not do as well on answering the questions. This is a completely fair judgement as I felt slightly unprepared. I think it is important that I start planning out the steps I will be taking throughout the three years and deadlines for certain outputs.

OHD_PRS_0122 Staying flexible: how to build an oral history archive

The second conference paper I presented. This one went better than the first one so that is positive.

Slides

Script

[slide two]

This is Seaton Delaval Hall. This National Trust property can be found in Northumberland just up the coast from Newcastle. Built in the 1720s the hall and its residents, the ‘Gay Delavals’ became renowned for wild parties and other shenanigans.

[slide three]

In 1822 the hall went up in flames severely damaging the property. This history is well represented in the collection that is housed at the hall.

[slide four]

What is less represented, however, is the hall’s more recent history: the community that looked after the hall after it burnt it down, the prisoner of war camps, and the medieval themed parties that the late Lord Hastings threw after the hall’s restoration.

For my PhD I will attempt to solve this issue of missing history by building an oral history archive. Oral history is a tool that has been employed many times to help represent the underrepresented in history. The challenge however is to build an archive with these oral histories. To help me explain how I am approaching this challenge I will use a metaphor.

[slide five]

This is a Ferrero Rocher. Through this yummy treat I will attempt to explain my project and the various layers of the process that need to be considered and analysed in order to be able to build an affective oral history archive.

[slide six]

The Hazelnut AKA a new storage system

The metaphorical hazelnut and core of this project is this storage system that will hold the oral histories I record. Why do I call it a storage system and not archive? I say this for three reasons, firstly because archives and oral history recordings are not the best of friends.

[slide seven]

The original framework that we use to structure and build archives is, and has always been, based around archiving mostly written documents. Searching through this type of material is easy because their content is visually apparent. These days you can, if they have been digitise, word search the documents very easily.

[slide eight]

Oral histories recordings (not the transcripts) struggle to fit into this framework, because their content can only be accessed if you sit down and listen to them. Listening back to these recordings can take a lot of time and can be hindered by outdated technology. This mismatch between the material and the place where it is stored often discourages people to reuse oral histories.

[slide nine]

I think the oral historian Micheal Frisch puts it best when he called oral history archives “a shoebox of unwatched home videos.” The content is there but the viewing a specific moment is an arduous task. Mining the hall’s community for stories and throwing them into a shoebox is exactly what I want to avoid with this PhD.

[slide ten]

At Seaton Delaval Hall I want to create a storage system that broadens access to and actively encourages reuse of the oral histories, in order to support the community that has looked after the hall for so many years.

The second reason I say storage system instead of archive is ….

[slide eleven]

because currently archives are struggling with adapting to advancing technology. In recent years there has been a push to digitise archives with the COVID-19 pandemic giving this process an exceptional boost.

[slide twelve]

However, this digitisation requires a lot of resources like money, time and manpower that many archives, especially smaller ones, simply do not have.

[slide thirteen]

In addition, what this push to digitise does, which it does in many sectors, is attempt to replace a human with a robot, who in my opinion is simply not up to the task. Typing into a search bar is not the same as asking an archivist for help.

[slide fourteen]

While a search bar is a tool one uses when researching, the archivist becomes a fellow researcher, making room for far more flexible and creative exploration.

[slide fifteen]

Thirdly, archives are rather static in comparison to the world outside of their brick and mortar walls.

[slide sixteen]

Especially in the last year there has been increasing pressure to review how we present our history as a society. This dynamic debate is not reflected in the way we store our historical documents.

[slide seventeen]

This limited reviewing and updating of our archives actually makes it harder to do research. The most obvious instance being how certain keywords become outdated over time, which is something that is especially prominent in the archiving of minorities’s histories such as LGBTQA+ and Black history.

[slide eighteen]

The way we traditionally build an archive does not fit with contemporary society. Archives were initial set up to preserve one view of history in one type format. They did not leave room for new technologies and new points of view. Now, archives are attempting to change this by rather awkwardly moving into the digital space without truly questioning how these digital tools affect the archiving process and researching in archives.

In order to create a new storage system I wish to let go of these traditions, these symbols and languages that we use to navigate oral histories, archives and the digital.

[slide nineteen]

I want to start with a blank canvas and build a storage system that not only reflects the technology and views found in society but also makes room for any further developments in these areas. Now, the next question is: how we might go about building this new system?

[slide twenty]

The chocolate filling AKA working together without killing each other

[slide twenty-one]

AKA collaborating! A truly fabulous buzzword that works very well in funding applications but in reality is really difficult to do. Why? Well, every field of research has its own type of

[slide twenty-two]

‘disciplinary upbringing.’

[slide twenty-three]

When I say ‘disciplinary upbringing’ I am referring to the lens that each field views things like language and methods of work through. In other words the

[slide twenty-four]

‘here we do things this way’ attitude.

[slide twenty-five]

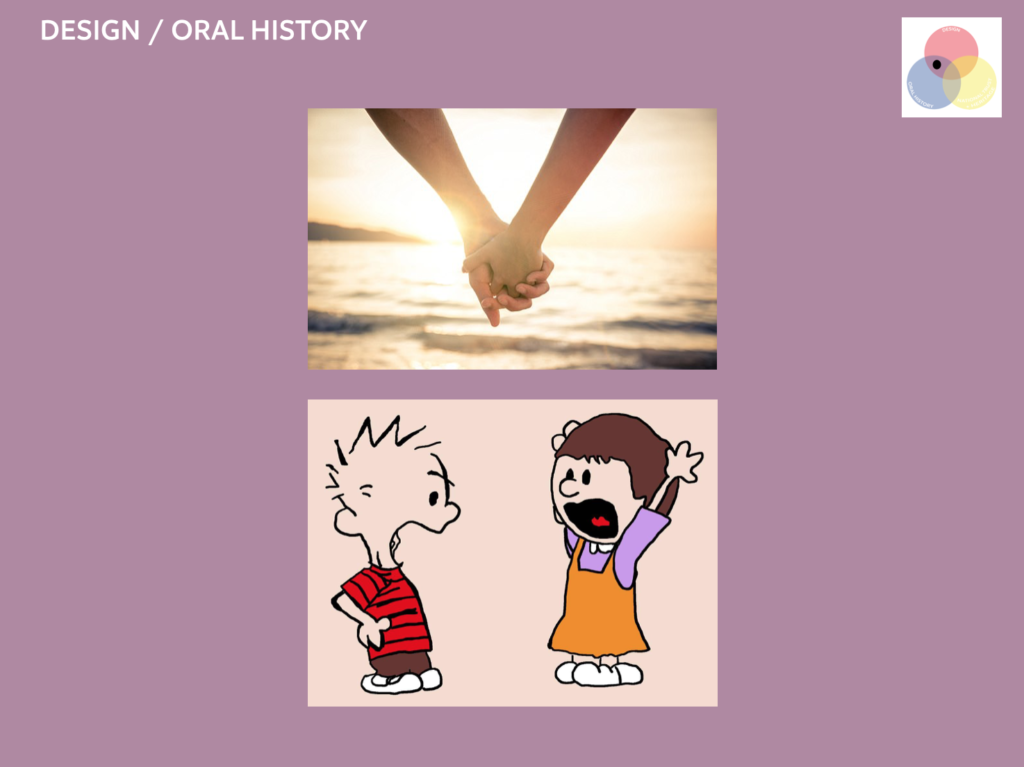

When people collaborate across disciplines they bring this lens, this disciplinary upbringing, with them so when the work starts everyone is viewing the challenge through separate and different lenses. This can lead to a lot clashes and plenty confusion.

So how do you solve this?

[slide twenty-six]

You could just say that people should leave their disciplinary upbringing at the door but that never works.

[slide twenty-seven]

Instead I intend on using these disciplinary upbringings to the advantage of the creative process by encouraging people to be open about them and in some cases even exaggerate them a bit. What this does is bring to light the various

[slide twenty-eight]

‘creative tensions’ that are present in the collaboration.

[slide twenty-nine]

For example in the context of this project where we have a collaboration between the fields of oral history, design and heritage you can find many creative tensions that are the consequence of differing disciplinary upbringings.

[slide thirty]

Between oral history and design there is the tension of the medium of communication; historians like writing and designers love a good visual.

[slide thirty-one]

I can tell you from experience that design and heritage work at dramatically different speeds. One of design’s key philosophies is “fail fast”, which is definitely not something would be mentioned in a National Trust meeting.

[slide thirty-two]

Finally, between oral history and heritage we find possibly the most challenging of creative tensions, which is differing opinions on the representation of history.

[slide thirty-three]

It is important to identify these creative tensions because they highlight issues that might have otherwise gone unseen if everyone had just been polite and kept their mouth shut.

[slide thirty-four]

Once they have been determined they function as a great source of information. This information needs to be drawn out through thorough questioning. It is essential to discover why the tension exists and how it might inform the creative process.

[slide thirty-five]

This does however mean that sometimes you might have to ask what seem like silly and obvious questions, because your disciplinary upbringing to begin with blocks you from fully understanding where other people are coming from. To complete the questioning to its fullest potential it is necessary to unpack any confusion no matter how small or trivial they might seem.

[slide thirty-six]

However the most fundamental thing within this chocolate filling of collaboration is — listening. One must always remember that you are not there to defend your disciplinary upbringing, you are there to solve a collective problem. When identifying and questioning creative tensions everyone must listen to all of those collaborating.

[slide thirty-seven]

Overall the chocolate filling represents something that can be very difficult, but with open minds, questioning and listening can be exceptionally fruitful.

[slide thirty-eight]

The Crunchy shell aka beyond the toolkit

A Ferrero Rocher is not complete without its crunchy shell and neither would this project. The crunchy shell in this context represents the legacy of the project. It is important to me that the project and the storage system does not end with the completion of this PhD.

[slide thirty-nine]

In order to avoid this I and everyone involved in the project shall thoroughly question and analyse the process of building this storage system. We need to reflect on what worked and what didn’t work. This questioning needs to be beyond which workshop activity was fun and whether we had enough time.

[slide forty]

What we need to do is extract questions that will help someone else set up a similar project. So instead of creating a rigid set of instructions with painfully particular processes, we offer future oral history projects questions that they must ask themselves before, during, and after the project. This hopefully will allow them to adapt the process to their needs and encourages them to think more creatively.

[slide thirty-nine]

Conclusion

Now I completely recognise the irony of me slamming the idea of a rigid sets of instructions and then ending on a how-to guide, but in my defence I had the title before I fully wrote the paper so please forgive me.

How to build an oral history archive

- Let go of your preconceptions of what an archive is (and also what the digital is)

- Work together by allowing creative tensions to occur and be questioned

- Reflect on your process and extract questions for future projects

The true aim of this how-to is to make sure that we do not end up in the same position we are now, where our archives no longer reflect society. The world is only going to get more complicated so if we do not leave room for questioning and change, archives are always going to be behind. This would be a disaster as archives on a macro scale are the keepers of our history and (in theory) hold the foundations of our collective identities as a people. On a more micro scale I have personally always found comfort in how archives keep documents that show everyday humanity, like a postcard to a fellow artist or a writer’s note to a partner.

So here is my how-to on making an oral history archive. Take it with you, try it out, tell me if it worked. I am going to do the same and probably change it many times in the next three years.