CDA development update

Here is a brief overview of how the PhD has changed since the project proposal split it into three sections. The first considers the significant changes that have occur globally in the last two years. The second discusses the change in the framing of the situation the PhD is addressing, reusing oral history recordings on heritage sites. And the third looks at the changes in design methodology and theory due to the environment I am designing in and for.

SECTION ONE: HISTORY HAPPENED

Since the writing of project proposal, the world experience significant changes including, the COVID-19 pandemic, further development in the conversation around the Britain’s colonial past, and a constant wave of climate disasters. The Trust did not escape the effects of these changes, having to furlough and make significant cuts to staff during the 2020 lockdown, publishing the report on sites with connections to the British Empire, including Seaton Delaval Hall, and wider actions for the Trust to achieve carbon net neutrality. In addition, the COVID-19 lockdowns also highlighted the public’s need for access to open spaces and nature, while storms, like Storm Arwen, highlighted the threat the climate crisis is to the Trust running open natural spaces. It is because of the changes in the Trust this project has also evolved and the project is unfolding in a very different environment than when it was originally proposed. The project therefore has to think about the environment impact of the designs it is developing and think about how the design might fit in the (post-)COVID structure of the Trust. In the original proposal the project was already thinking about a 360˚ interpretation of the hall but now this seems more important than ever.

It is also interesting to note, while it is true that National Trust sites are to a certain extend run autonomously, they do not operate in a vacuum. National Trust sites function inside the wider structure of the Trust, an extensively complicated network of rules, regulations, and resources. I believe the influence this structure has on the project was slightly underestimated at the time of writing the project proposal. For example, the Trust’s digital infrastructure which has strict rules and regulations about digital storage has become quite the barrier, the extent of which had not really been realised before the start of the project.

SECTION TWO: BUILDING THE FOUNDATIONS

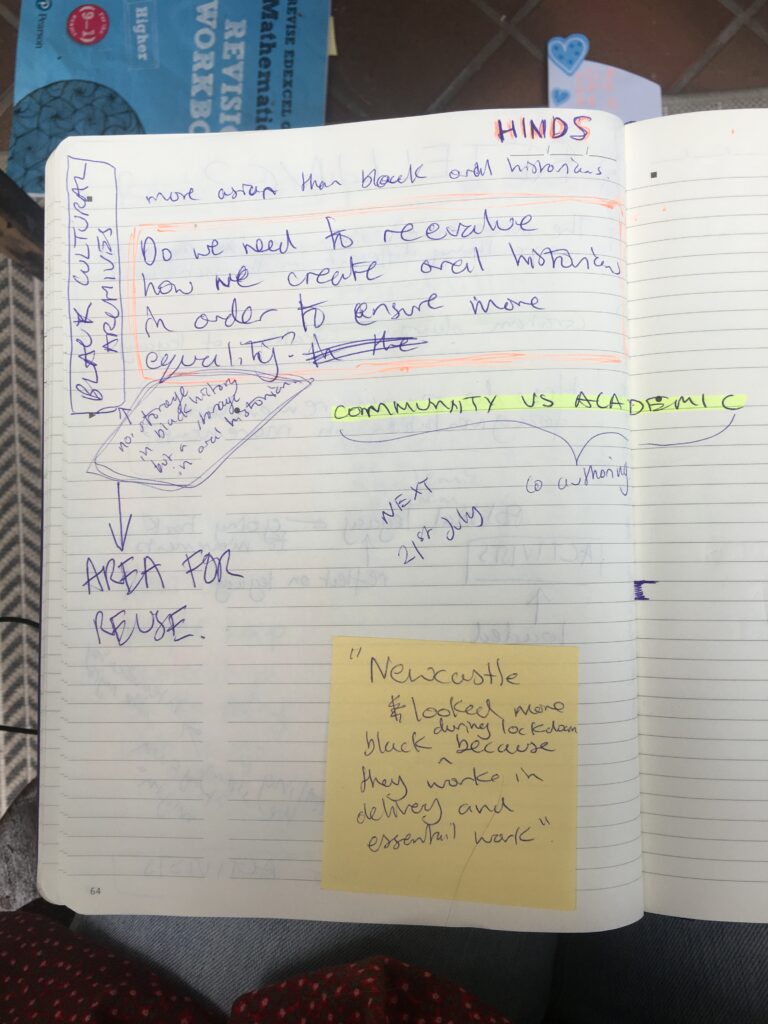

In the summary of the project proposal it is written that “the PhD would generate, in partnership, new knowledge in understanding and addressing visitors’ active engagement in interpreting the past through reusing a National Trust oral history archive.” The big assumption made here was that “a National Trust oral history archive” was either already in existence or would have been easy to set up. What the last two years have revealed is that this part of the task is easier said than done and the struggle in setting up oral history archives that allow reuse is not unique to the National Trust. After I did a deep dive into the many attempts to make oral history recording more reuse friendly through digital tools, it became clear something more fundamental was not being addressed. Most frequently the downfall of these digital solutions was the projects coming to the end of their funding, meaning there was no money to support the maintenance needed to keep the technology running, which eventually resulted in their deterioration.

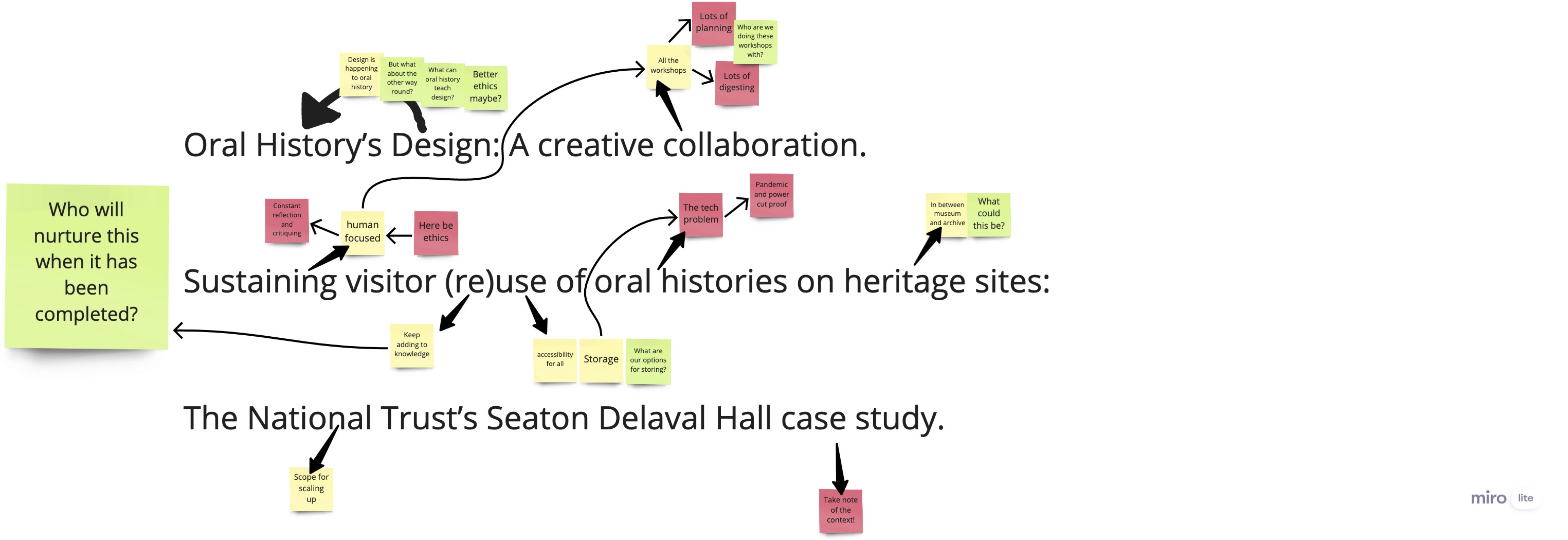

If we return to part of the original title of the PhD, “sustaining visitor (re)use”, the project initial was about building a system to allow visitor interpretation of oral history recordings. However, two years down the line “sustaining visitor (re)use” seems only achievable if at first, we create a solid foundation on which a system for visitor interpretation can be build and maintained. In order to create these foundations, there needs to be a focus on maintenance and the resources needed to support the storage of oral history recordings, which is something that has been missing from other endeavours into oral history recordings accessible. The resources needed will obviously include labour and money but also energy. As the large carbon footprint of internet servers and the storing of digital files is being realised. This project also needs to think about how we are able to store oral history recordings in the most energy efficient way possible, while still ensuring they are accessible and reusable to a wide range of people. This is especially important with the Trust’s aims for carbon neutrality.

SECTION THREE: CHANGE IN METHODOLOGY

Back in the original proposal Roberto Verganti’s idea of a technological epiphany is mentioned as a possible route for the PhD. However as written in the first section the Trust’s digital infrastructure is slightly rigid and is likely to not accommodate any radical technological innovation, meaning that a technological epiphany is unlikely. What we can still take from Verganti is his ideas around a change in meaning. What does it mean to do oral history on heritage sites? And how does oral history benefit heritage sites in the long term, beyond the idea of volunteer and visitor engagement within a set project timeline? Alongside Verganti’s idea of a change in meaning I have taken on design theory from Cameron Tonkinwise about ‘design for transitions’, which involves thinking about the life of designs outside of the project timeline and Victor Papenek’s six elements of function that lead to a successful design: use, method, need, aesthetic, telesis, association.

With the project design practice there has been another change. Instead of following a step-by-step process of researching, developing a prototype, testing and iteration. I have opted to use ‘infrastructuring’; researching and mapping the existing structure of an institution or system to better understand and communicate where any possible design solutions might fit. And ‘design fiction’ or scenario building as a low-risk method to harvest feedback on possible designs instead of the high-risk method of live testing and iteration. Design fiction/scenario building also seems to be an excellent way to communicate across disciplines.