Rose Gilroy reports on the first of a series of events asking tough questions about later life.

24 men and women in their 50s and 60s were invited to Northern Stage in July 2013 to participate in ‘conversations’ about ageing.

Previous projects undertaken by the researchers* on the viability of co-housing for older people aimed to address widespread dissatisfaction with the physical and social architecture of specialist housing. Conversations evolved which were less about co-housing and where we might live and more about how we might live. Creative approaches such as drawing and role play led people to explore their views on later life very deeply.

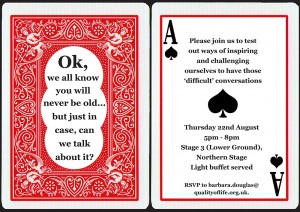

It isn’t easy to have difficult conversations about what will happen when we get old – our families and close friends may not want to talk about it either. We tried to reflect this in our choice of invitation, printed on a playing card as a reminder that often we leave a ‘good’ old age to chance. Participants were chosen to include those both in and out of waged work and because they were known as people who were prepared to engage by the researchers.

Cartoons that made wry comments on ageing were scattered on the table to help break the ice. Paper table cloths were used and people were encouraged to write down their thoughts or observations.

Sets of questions, again on playing cards, were placed on each table of four people. The groups were encouraged to look at the questions and, if one struck a chord, they should use it to engage the others. Blank cards were also provided so that participants might write their own.

At the close, participants were encouraged to scribble on the graffiti sheets pinned on the wall to share their reflections on their experience, its broader application as a method and who else ought to be included in these conversations.

We were nervous, would people respond to what we thought might be key questions:

How do I avoid empty days? How do I find recognition when I no longer have formal status? How and where will technology feature in my life? How can I manage transitions? How do I celebrate my achievements? How can I keep a supportive network of people round me? Where do I want to live and how?

The response was very positive. Some participants found the evening challenging but commented “we need the space to explore our own feelings on how to live, not just how others organise it.” There was enthusiasm for the method of using conversation cards and many suggestions about making this into a kit for naturally occurring groups to use.

Questions that occurred to us as a result of this event included:

Might younger people have ideas to put forward; what about older people from minority communities – do they have similar issues? Men seem to find it more difficult to open up about these issues so how about engaging men only groups?

The issues raised are currently being analysed in preparation for further `conversations` and will be taken forward into publications and (possibly) a conversation kit.

*Researchers: Rose Gilroy, School of Architecture, Planning and Landscape; Barbara Douglas, Quality of Life Partnership; Moyra Riseborough, Independent Housing Consultant