Click for summary

Adeline Cooper, a Quaker reformist and musician with royal connections, is credited with the ‘club’ membership aspect of this movement. Despite no biography, we do know a bit about her and the club she founded in Westminster, but very little about her influence on music in clubs.

For those familiar with a beer-filled night out at Britain’s working men’s clubs, it’s a shock to learn that their early years are attributed to Victorian teetotal minister Reverend Henry Solly. But Solly credited the success of the movement to someone else: a professional musician turned proto-feminist.

Adeline Cooper was not the kind of musician nowadays associated with clubs – neither a dancer, nor comic entertainer nor ballad singer – but an aspiring star of the concert hall and performer for the queen. Cooper’s career began as a young singer whose performances – mostly operatic – were praised by the London press. By the start of the club and institute movement in the 1860s, she had been a music teacher, written her own compositions and ballads, and even gained the unauthorised title ‘Pianiste to the Queen’.

But in 1859, Cooper took a sudden hard turn into improving and reforming the working classes, and never, it seemed, looked back. She set up one of the first ever working men’s clubs and joined the first Council of the Working Men’s Club and Institute Union where she argued for the importance of the ‘club’ element in popularising the movement. But what influence, if any, did she have on the presence of music in clubs and institutes?

Musical career

Cooper’s performing career came towards the end of half a century in which unmarried women were increasingly working as independent musicians, but they needed to contend with economic competition. Despite being complimented for ‘a rich and flexible voice, a pure taste, and much feeling’, her theatre engagements were mostly short and commercially unsuccessful. As was common for plenty of performers and composers back then as much as now, she supplemented her work with music teaching, offering piano and singing lessons to the nobility and gentry.

In 1841, Cooper made her first connection with the burgeoning industry of sheet music publishing, performing ‘The Alpine Shepherdess’ a ‘Tyrolien’ composed for her by the French Jaquerod de l’Isle – complete with yodels. Her yodelling must have been acceptable to audiences, as another custom Tyrolien, ‘Happy Land’ was then composed for her and two others by Edward Rimbault.

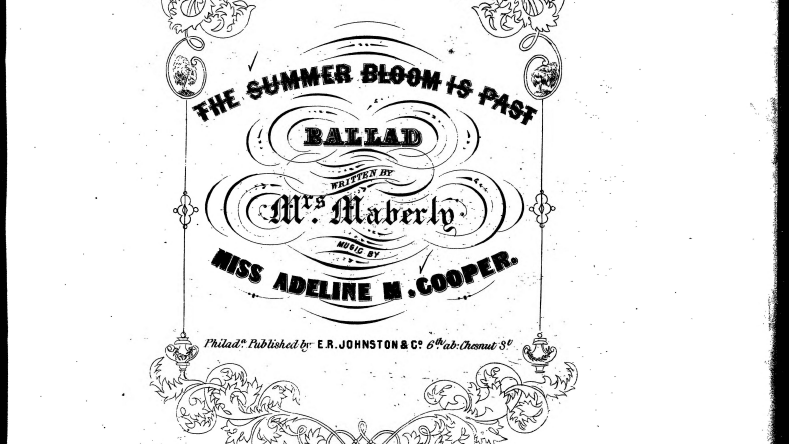

Cooper then tried her hand at professional composition. The earliest surviving piece is ‘Isaline’s song’, or ‘The Summer Bloom is Past’, a simple 1843 ballad for medium voice and piano with lyrics by Catherine Charlotte Maberly, Irish author of historical fiction. Written to accompany Maberly’s second novel, The Love Match, it is probably Cooper’s most enjoyable piece, the piano part flowing well under the hands, with a memorable vocal melody including large leaps that betray her fashionable Tyrolien yodel influences.

The majority of Cooper’s surviving compositions were written for solo piano, in the style of popular dances. In 1850 she dedicated a set of waltzes to the U.S. President General Zachary Taylor, and a polka to Washington Irving, author of The Legend of Sleepy Hollow. Irving replied humorously to this ‘flattering testimonial’ that he was too old to dance the polka, and his house ‘too small to furnish a polking room.’

Later in the decade, she relentlessly pushed for the patronage – or, at minimum, endorsement – of her work by Queen Victoria. The performance of Cooper’s ‘Havelock Grand March’, written for the British Army general and his grieving wife, was sanctioned for the band of the Scots Fusilier Guards at Windsor. Although the performance went ahead, the queen insisted, despite being a strong supporter of the arts, that she never ‘allows her home to be made use of as a means of advertising, or promoting the case, of musical or other works’.

Cooper’s compositions are frustratingly basic harmonically and formally, and it’s likely that she grew disenchanted by the limited recognition they received. In 1860, after a number of compositions for religious or charitable purposes, her efforts as a composer came to an end.

Social reformer and club founder

While she had been attempting to carve out a reputation as performer, teacher and composer, Adeline Cooper somehow developed an acute interest in the wellbeing of working class women and, by proxy, men. Working men, she believed, were making their wives’ and children’s lives miserable because of the financial and moral ruin encouraged by the public house. Similar, but teetotal, spaces would improve the wellbeing of women, she asserted, by turning men into good husbands and fathers.

Seemingly abandoning her public musical life, she bought a pub in Westminster and converted it into a school for children living in poverty, joining the ‘ragged school’ movement supported by Charles Dickens. A year later, she started up one of the first ever (by name, at least) working men’s clubs, open during the evenings and offering newspapers, draughts, chess, coffee and ginger beer for a small subscription.

Known as the Duck Lane Club, the institution also provided educational classes, and free lectures for members and their families. Before long, it developed its own systems of mutual financial support, including a scheme to help costermongers (street sellers) to buy their own barrows. The club was remodelled and expanded, until it became the architecturally imposing Westminster Working Men’s Club and Reading Rooms, containing a library, kitchen, lecture room and club room, attached to a dwelling-house providing charitable accommodation for dozens of families and a cooperative store.

Off the back of this venture, Cooper was treated as something of a specialist in setting up clubs and institutes. She had been advised by her male friends that the club should be self-managing, based on their experiences in the more elite West End clubs and the Reform Club. This seems to have worked: it was costermongers who first populated the club in Westminster, and a costermonger, John Bebbington, who became its secretary. Bebbington joined Cooper on the first Council of the Working Men’s Club and Institute Union, speaking at the Union’s inaugural meeting in 1862, and the two were described as some of its hardest working members.

Solly took Cooper’s advice very seriously, especially on the importance of ‘clubs’ rather than merely ‘institutes’. He also supported the idea that the movement might eventually replace its philanthropist managers with workers themselves. This was crucial for encouraging membership from the working class who had been put off by the top-down formalities of unsuccessful Mechanics’ Institutes in the decades prior.

Musical advocacy?

The life of Adeline Cooper spanned two worlds: music and clubs – it seems obvious that the two would cross over. Cooper’s skills and passions might have been put to good use in ensuring there were opportunities for music performance and education in her club, even getting involved herself as a singer, pianist or teacher. It’s tempting to also imagine her advocating for the importance of music in those early days of the Club and Institute Union, given the involvement of clubs in the world of music hall and variety shows.

But there are simply too few records to prove any of this (and it’s a problem across club history as a whole!). The catalogue description of her letters at the National Archives lists singing classes among her ‘self help schemes’, the rest of which were certainly hosted at her club/institute/library/cooperative complex in Westminster. And at one point, the lodging rooms housed four blind street-musicians – this set-up of club-plus-accommodation would have been fantastic for touring performers in the heyday of Clubland. But this is all the evidence we have that her two worlds ever collided.

It’s highly likely that Cooper shared the view of many of her peers that music, of the right kind, had a civilising effect on all classes. She was in correspondence with the poet Matthew Arnold, who popularised the phrase ‘sweetness and light’ to refer to the need for beauty and intelligence within efforts to reform society and improve material conditions.

However, if Adeline Cooper – later Harrison, wife of the painter John Barker Harrison – gave any music- or arts-related advice to the Union and its reform efforts, the evidence has been lost. The minutes of the Union’s first decade or so have disappeared, and any remaining records of the early years must have been victims of the fire that destroyed much of the archives of the Union’s offices.

After she became involved in the club and institute movement, very little was mentioned of Cooper’s previous musical life, especially as a singer. The blog English Romantic Opera speculates that ‘[p]ossibly it was thought a little demeaning to her new position to admit it.’ Although female singers were increasingly viewed as professional artists during her earlier career, most of the press remained suspicious of the appropriateness of such a lifestyle. It could well be this attitude that kept the social reformer from pursuing a musical career any further, and from embedding herself into the music history of the club movement.

So did Adeline Cooper kick off the working men’s club movement? Not really, not on her own. But Solly might be right that she was key to its success: just like upper-class gentlemen, busy manual labourers didn’t want to spend their spare time attending the institutes that had been pushed at them for decades; they wanted a club – somewhere to belong.

It’s hard to say whether she saw music as ancillary to this mission – I’d like to think so. But the alternative possibility, where music – specific genres, or as a whole – was connected with impropriety, shame, classlessness and a life unsuited for a well-to-do woman, hints at an equally interesting story.

Image of the Alpine Shepherdess © The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.