The food system, holistically considered, accounts for around a quarter of all anthropogenic emissions and can contribute greatly to attempts at mitigation due to the great potential of better land management in storing carbon. Recognising the role of agriculture in tackling climate change, the COP 23 meeting, held in Fiji in 2017, decided on a Koronivia Joint Work on Agriculture. Despite this initiative, in Glasgow, relatively few discussions took place on the role of the food system in relation to climate change, and even fewer considered the important contribution played by the consumption of animal products. In my previous post I pointed out that many non-vegan diets compare poorly with vegan diets when we consider the climate change impacts of human dietary choices as they contribute disproportionately to the release of carbon dioxide, nitrous oxide, and methane, and squander opportunities for carbon sequestration. In this post I report on some discussions that took place at COP 26 in relation to the consumption of animal products.

Making the farming of animals more efficient

People who were involved in discussions on the theme, however, recognised that emissions from the food system must decline. Many policy-makers focused on the idea of making the farming of animals more efficient. Amongst these were Tom Vilsack, Secretary of Agriculture, USA, and Damien O’Connor, Minister of Agriculture of New Zealand, who spoke of the desire to create ‘more efficient cows’, explaining also that the number of sheep in New Zealand had halved in the last 40 years, without any loss in productivity. Harry Kimtai, Kenya’s Principal Secretary State Department for Livestock, claimed that 1.2 billion people in the world rely directly on ‘livestock’ and that over 87% of Kenyan land is only suitable for ‘livestock’ farming due to inherent climatic conditions that do not support crop farming. He added that farmers were seeking to reduce ‘livestock’ contributions through better animal management, better genetics, and the use of feed additives. Several researchers were aligned with this technological agenda, including Sinead Waters (Livestock Research Group of the Global Research Alliance for Climate Change) and Simon Oosting (Wageningen), as well as Minette Batters, the president of the National Farmers Union of England. Batters appeared to be aware of vegan challenges to a paradigm that relies mainly on the hope for technological solutions, stating that ‘we should listen to the eco-workers, not the eco-warriors’ and that ‘we need to end this perverse debate of meat versus plant’ and ‘the toxicity of this debate’.

It was not clear what debate she referred to here. A big shortcoming of the COP 26 meetings on the food system was that the sessions that took place did not involve much debate. Rather, the debate took place in between the sessions, at least to the extent that the same audience attended diverse sessions and debated amongst themselves. What I mean by this is that many sessions came across as talking shops for like-minded people. There was not much opportunity or need for speakers to get outside their echo-chambers. Some sessions promoted technological solutions; others challenged such an approach. Never the two approaches shall meet.

Questioning dominant values on the consumption of animals products

Sessions that adopted the latter approach included mainly speakers from non-governmental organisations. Most prominent in this regard was Sailesh Rao from Climate Healers, who presented several press conferences on ‘the cow in the room’. It is a shame that someone who made some implausible claims was given so much space to speak, as some of the views that Sailesh aired included the claim that 87% of the climate change crisis is caused by animal agriculture and that ‘heart disease is food poisoning, that is all it is’. Dale Vince, chair of Ecotricity and of Forest Green Rovers, spoke at one of these sessions, reporting that ‘green gas’ or ‘gas from grass’ is already provided to some customers who get their energy from Ecotricity, a big energy provider in the UK, and that this use of grass was much more sustainable compared to animal grazing. The health argument was also advanced by Kenneth Liao, a doctor from the Buddhist Tzu Chi Foundation, who talked about faith-based compassion to promote vegan diets, and who mentioned that the Dalin Tzu Chi Hospital in Taiwan is the only fully vegetarian hospital in Asia. Paul Behrens (Leiden University) spoke about the health of our oceans being damaged by trawling, a very important issue that is frequently neglected in food discussions that tend to focus on farming.

Of all the non-governmental speakers, I was most impressed by the contributions to the discussion from Carina Millstone from Feedback and from Helen Harwatt from Chatham House and Harvard Law School. Harwatt mentioned that about half of all inhabitable land is used for agriculture, that 78% of agricultural land is used for animal agriculture, and that animal agriculture provides only 18% of our calories and 37% of our protein. She also talked about the need to reinstate coastal vegetation, much of which has been lost through the killing of predator fish who no longer eat the herbivorous fish who consume much of our coastal vegetation.

Reporting that Berlin universities have decided to cut animal bodies from their menus, ProVeg International’s Raphaël Podselver was keen to talk about policy initiatives to reduce the consumption of animal products, where he mentioned the EU’s ‘Farm to Fork Strategy’, Amsterdam City Council announcing that it wants to be 50% plant-based by 2030, and Helsinki City Council no longer offering the bodies of animals at events organised by the city. Nick Palmer from Compassion in World Farming also stressed the need to develop policies, demanding governmental support from countries in what he called the ‘developed world’ for plant-based alternatives, and the introduction of a tax on the consumption of animal products.

So, what did policy-makers think about all this?

Barry Gardiner, the Labour MP for Brent North, was one of very few politicians who took part in a discussion that focused on a discussion of values underlying the food system. He reported similar figures as those that Harwatt mentioned, saying that 83% of the land is used to produce animal products, including feed, and that the sector supplies 37% of the protein and 18% of the carbohydrates that human beings consume. He reacted against those who focused on technological solutions, saying that the development of feed additives is trying to put a sticking plaster on the main issue, which is that we should focus on how we ought to ‘treat other beings’. He said that we must reduce ‘meat’ consumption and tackle deforestation, adding that ‘the biggest financiers of the two largest beef companies in the Amazon are in the UK’.

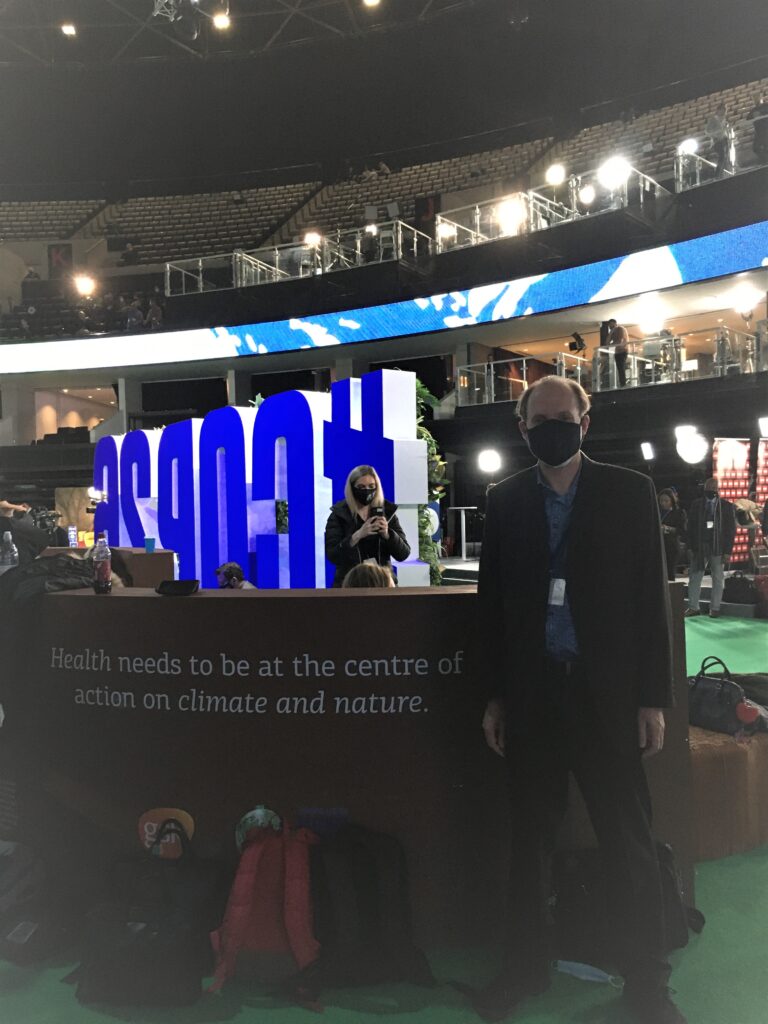

During COP 26 (on 7 November 2021), George Eustice, Secretary of State for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs of the United Kingdom, appeared on the Andrew Marr Show (BBC), where he was asked about introducing a tax on some animal products. He responded: ‘We are not going to have an arbitrary meat tax or meat levy (…) that has never been on the cards, I have never supported it.’ Whilst Ed Miliband, the Shadow Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy of the United Kingdom, did not attend any of the sessions that I attended on the role of the food system, I had a brief meeting with him in the Action Zone. He was more open towards the idea of introducing a tax on some animal products, saying: ‘I wonder what we should do. Do you think we should introduce a meat tax?’ Whilst I did not have the opportunity to answer this question at the time, I sent him a detailed answer by email afterwards. I asked him whether he thought that the UK Government should make a vegan option mandatory in all restaurants operated by the public sector, where he said in reply: ‘I would be in support of that.’

Whilst Miliband’s positive answer is a step in the right direction, I believe that we need to move beyond this. Before the COP 26 meeting in Glasgow, I was funded by Newcastle University’s Engagement and Place Fund to co-author a policy briefing with Charlotte Blattner (University of Berne), which we sent to the Vegan Society to help them to prepare their policy briefing for COP 26. It recommended the following policy objectives:

• The current insulation of the agricultural sector through various mechanisms of ‘agricultural exceptionalism’ must be dismantled.

• A predominantly plant-based global agricultural system must be established.

• The transition towards a predominantly plant-based global agricultural system must occur without jeopardising the well-being of any human beings.

• More research is needed to determine how a transition towards a predominantly plant-based global agricultural system would help us to mitigate the climate crisis.

Whilst these objectives may sound unrealistic, I believe that they are based on sound values. If politics should be based on ethics, policies should be created to prevent many people from adopting non-vegan diets.

What do these objectives mean, more concretely?

For many, if not most relatively affluent nations, including countries like the United Kingdom, the 27 nations of the European Union, Australia, New Zealand, and the United States of America, there is no reason mandatory veganism is not an option. If the transition is handled carefully, the negative socio-ecological impacts of vegan diets that are sourced from nations with temperate climates, relatively fertile soils, relatively good (financial means to develop) technologies, relatively stable political situations, and relatively good access to water, would be smaller than the negative socio-ecological impacts of non-vegan diets.

This situation contrasts starkly with the situation of many farmers in Africa, for example, where many farmers cannot benefit from temperate climates, relatively fertile soils, relatively good technologies, relatively stable political regimes, and relatively good access to water sources. In some African nations, farmers may only be able to ensure a good livelihood for themselves and their families if they continue to be able to use animals to graze grassland that may be very unsuitable for arable cultivation. Indeed, it may increasingly become less suitable because of the climate crisis, which has disproportionately negative impacts upon many of those who are the most vulnerable already.

However, even in relatively affluent nations, policies must be created to ensure that the transition does not make those who are most vulnerable even more vulnerable. The principles adopted by the ‘Just Transition’ movement may help to facilitate this. For example, those whose income currently depends on the farmed animals’ sector must still be able to secure good livelihoods for themselves and their families, and those who currently struggle to buy good food must be empowered to access good food.

So, to sum up: the general principle is that people should adopt those diets that produce the fewest negative global health impacts. Not all non-vegan diets should be abandoned. Indeed, there is a moral imperative for some people to adopt non-vegan diets. In many situations, adopting this principle implies a moral imperative to adopt a vegan diet. Those who deviate from the general principle prioritise their personal taste over their moral duty. In my final blog post related to COP 26 I will address the question what individuals can and should do, in spite of the fact that the United Nations and participating nations continue to take this situation seriously.