As discussed in Part 1, OR-causality is a useful and important part of specifying circuits, and with our recently released tool (https://github.com/tuura/concepts), we needed to include OR-causality in the translation from concepts to STGs.

To include this in the tool, we needed to design an algorithm which can take OR-causality, and seamlessly use it in conjunction with standard AND-causality.

This part will detail our algorithm. Our tool is written in Haskell, and while some of the algorithm is based on Haskell constructs, we will aim to use pseudo code to describe this algorithm.

OR-causality, an algorithm

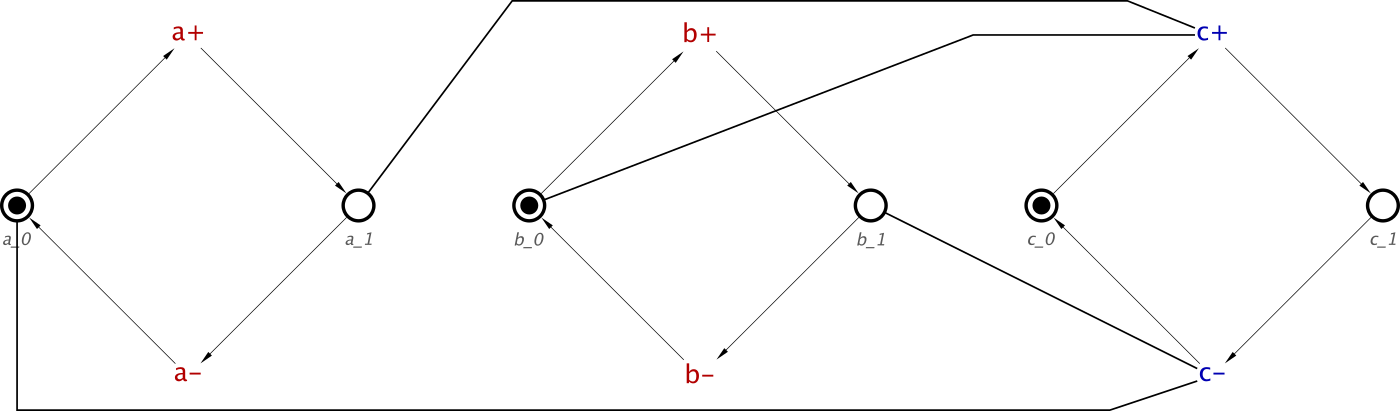

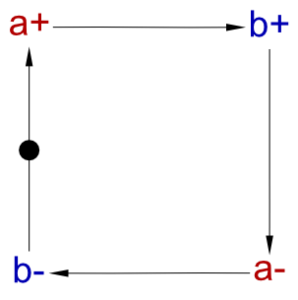

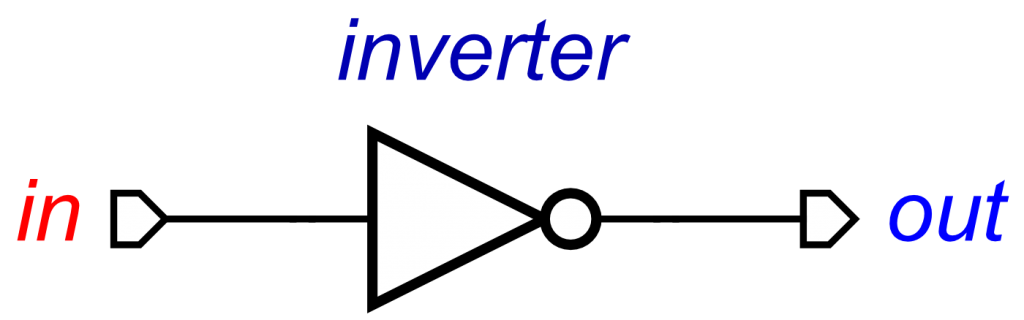

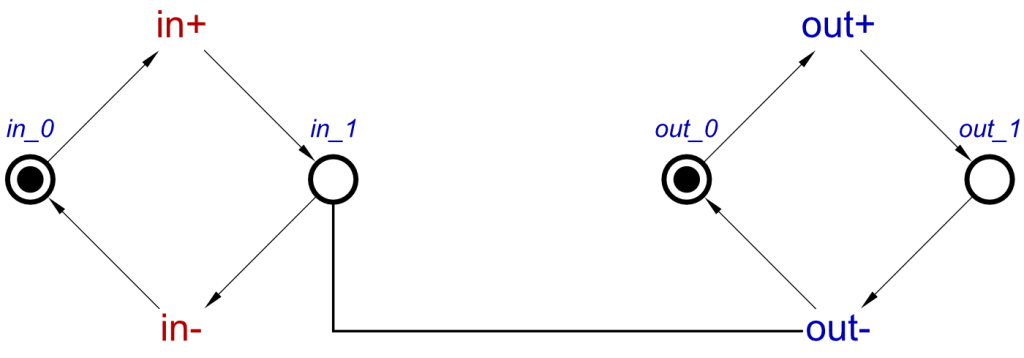

For an example to explain this, we will use Example 2 from Part 1 of this post, an OR-Gate with a single AND-causality. This will display well OR- and AND-causality interaction.

Let’s just remind ourselves of the concepts for this:

circuit = orGate a b c ⋄ buffer d c

This can also be described using signal-level concepts:

circuit = [a+, b+] ~|~> c+ ⋄ a- ⇝ c- ⋄ b- ⇝ c- ⋄ d+ ⇝ c+ ⋄ d- ⇝ c-

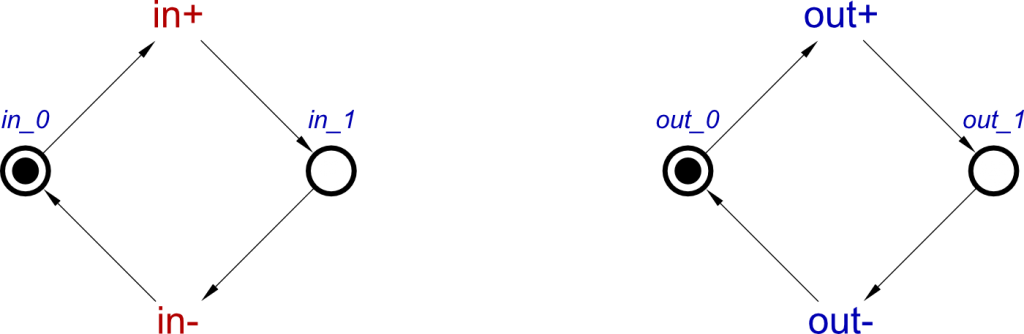

The first thing we need to think about is how we store this information. As we said in Part 1, OR-causality is described by listing the possible causes for a single effect, for example from:

[a+, b+] ~|~> c+

We can see that a+ and b+ are the possible causes for the c+ effect transition.

Therefore, we can list OR-causality as a list of causes for each effect. However, this will cause issues when there is more than one list of OR-causality causes for a single effect, but we will discuss this later.

This also causes an issue with AND-causality causes, as we cannot simply add these to the list of OR-causality causes, as this would change the type of causality from AND to OR.

To solve this problem, we treat each type of causality as a separate list, where OR-causality is a list of at least two causes, and AND-causality is a list with a single cause. These are stored with the corresponding effect to the causality. So, for c+ in this example, we would store:

Causes: [a+, b+] & Effect: c+

Causes: [d+] & Effect: c+

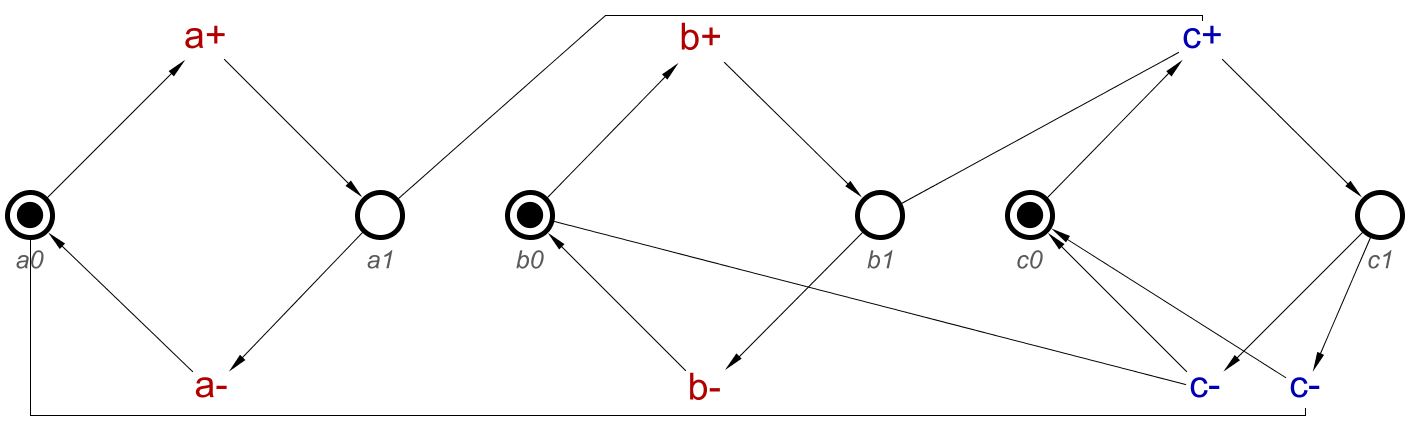

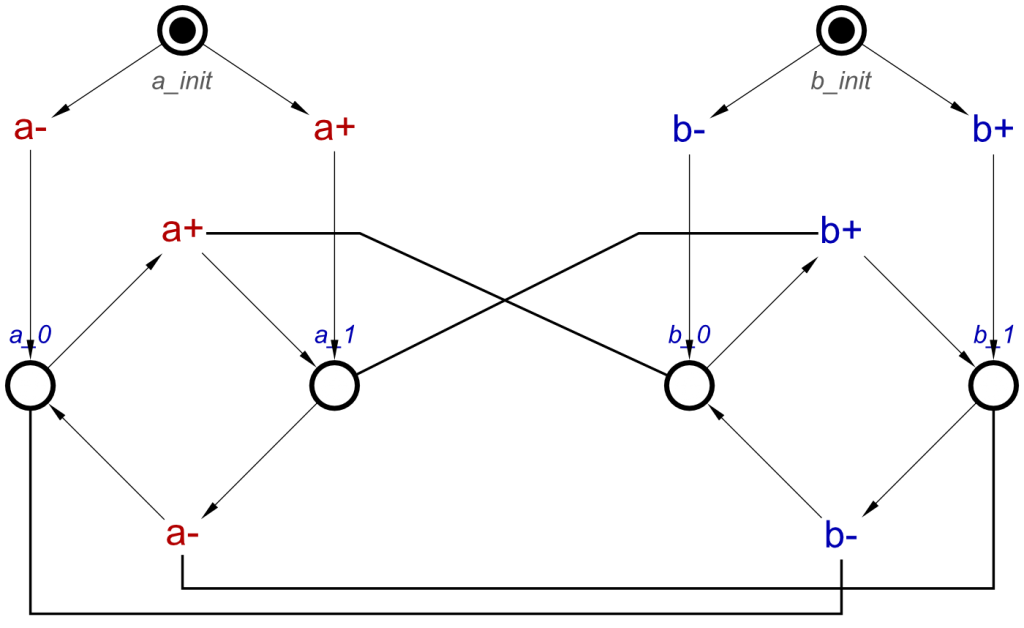

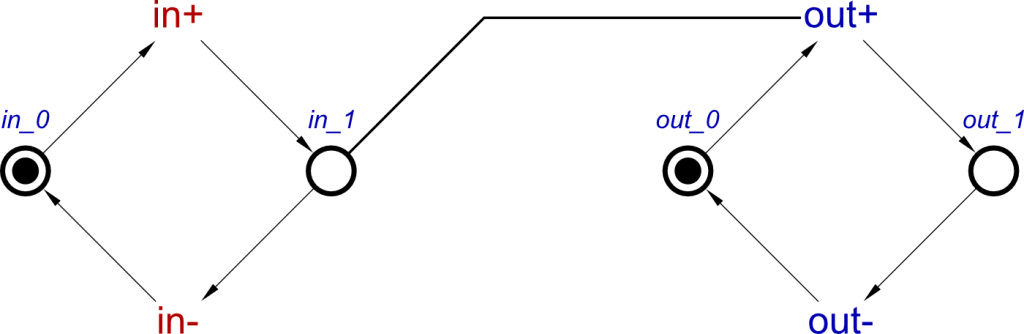

Now, looking back at the example, the resulting STG features two c+ transitions, but how do we arrive at the number of transitions we need?

The next step in this algorithm is to rearrange these stored lists of effects so we then have the cause transitions required for each of the resulting effect transitions, c+ in this case, to be able to occur. This is done using the Cartesian Product, commonly used in mathematics to “expand the brackets”, which, due to how lists are stored, also applies here. The Cartesian product will produce a number of results, based on the size of the inputs. In this case, we have two lists, one of size 2 and one of size 1. Multiplying these numbers gives us 2 results, and thus, 2 effect transitions.

With that in mind, we need to perform the Cartesian product on these two lists, which will provide us with two new lists which are the effects required per cause transition. This will be performed as follows:

1 – [a+, b+] * [d+] — The original lists

2 – [a+ * d+], [b+ * d+] — A list of lists after performing the Cartesian product on 1

2 holds a list of lists, each list being the required effects for a single transition to occur, one requiring both a+ and d+, the other requiring both b+ and d+. Due d+ being in an AND-causality relationship with c+, it is required to have occurred, regardless of whether a+ or b+ has occurred.

Now we need to include the two c+ transitions in the output of the tool, to be included when importing into Workcraft. The tool outputs the STG in dotG format, which is commonly used by existing tools which work with STGs. This format allows for the inclusion of more than of the same signal transition. The first of each transition will be output as expected, c+, but a second one will be output as c+/1. A third will be known as c+/2, and so on. For this example we will have c+ and c+/1.

With this information, we can now apply the specific transitions to the lists we have for each transition:

Causes: [a+, d+] & Effect: [c+]

Causes: [b+, d+] & Effect: [c+/1]

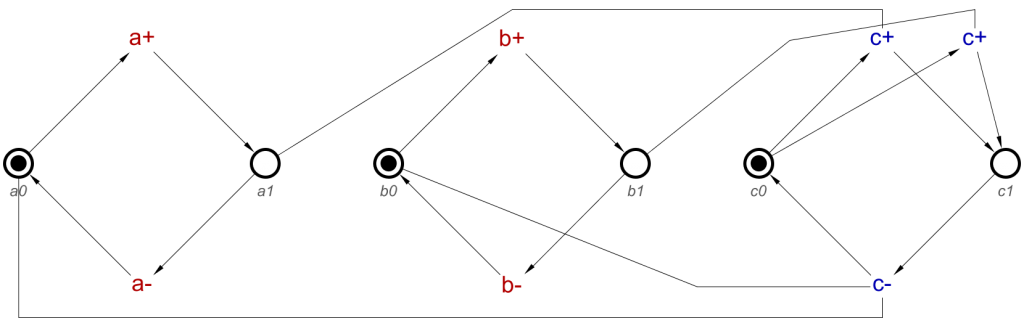

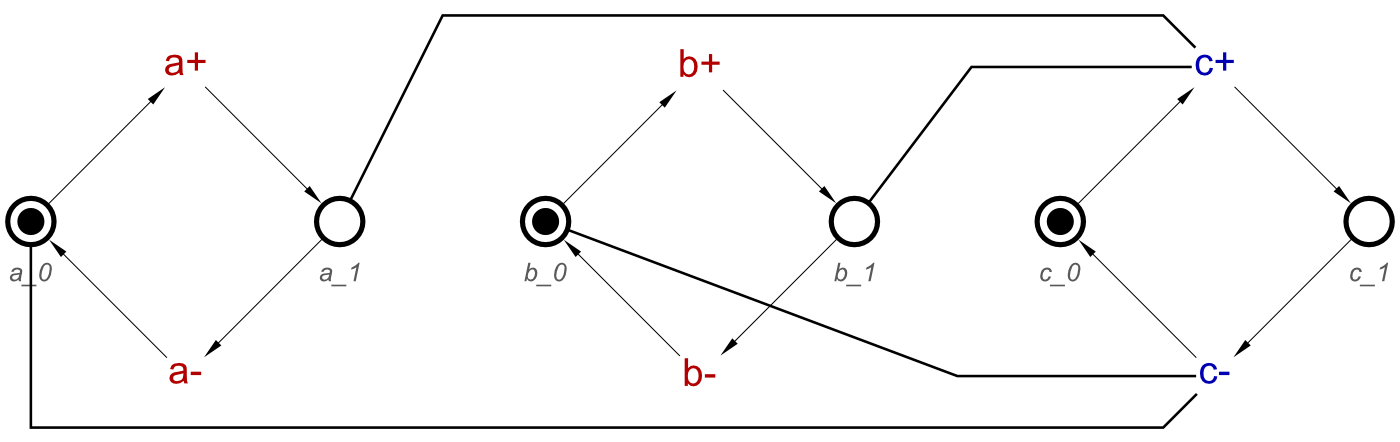

And this can now be converted to the transitions and read-arcs as expected, to produce the STG shown in Example 2 in Part 1 of this blog post.

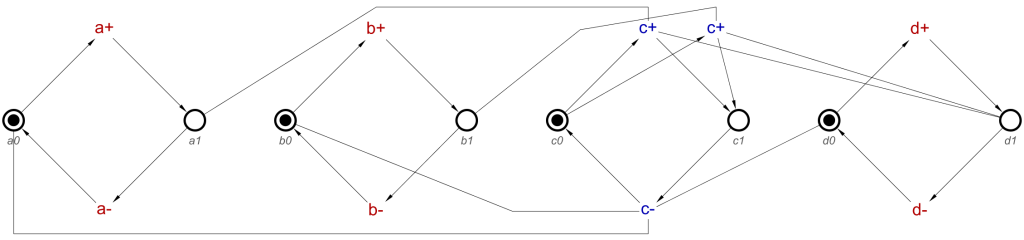

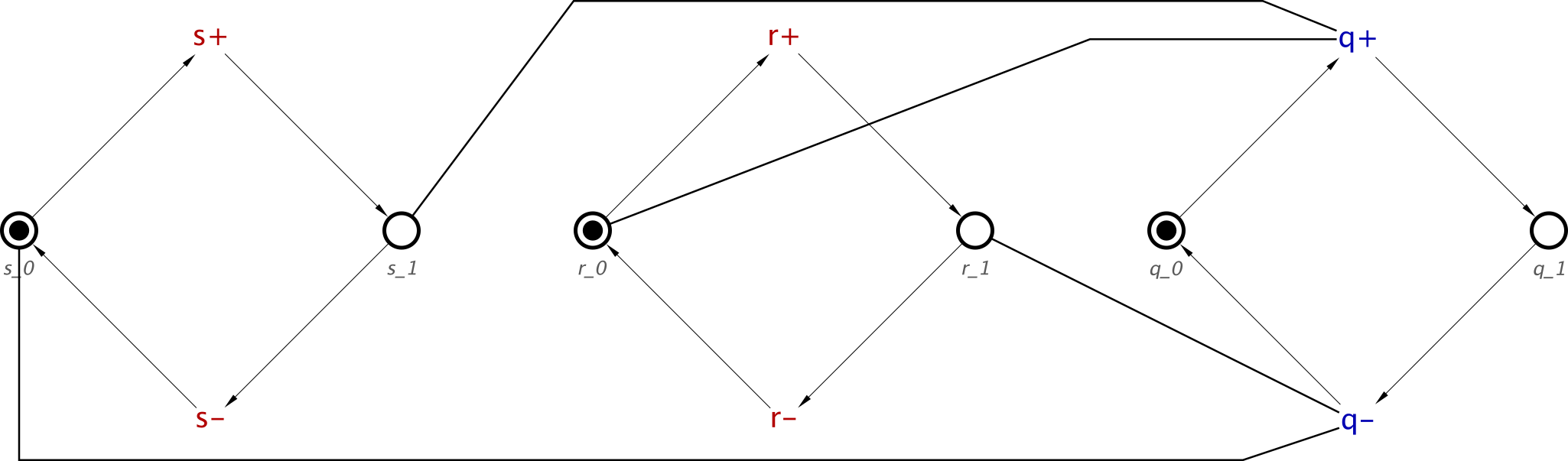

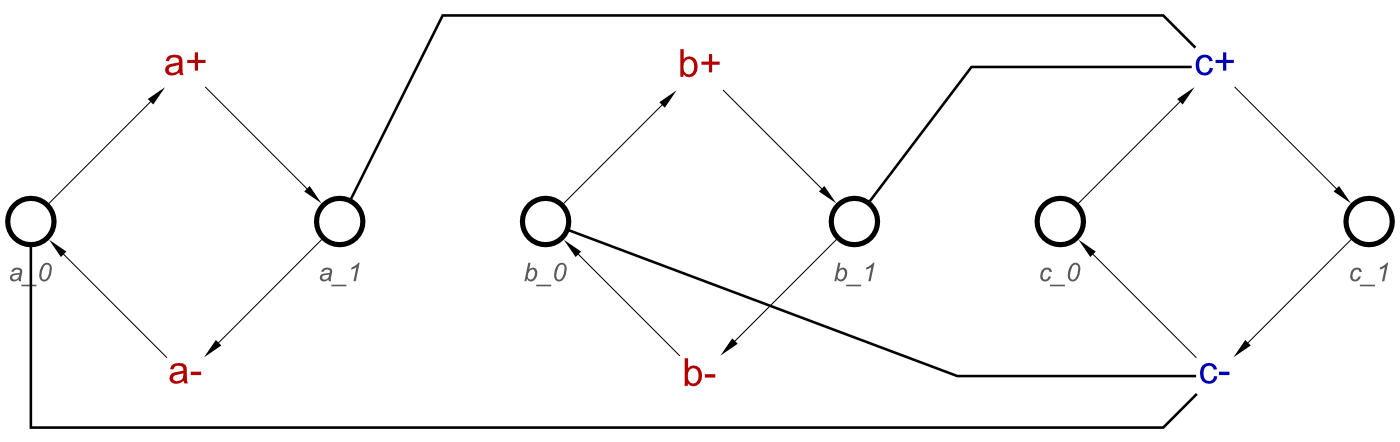

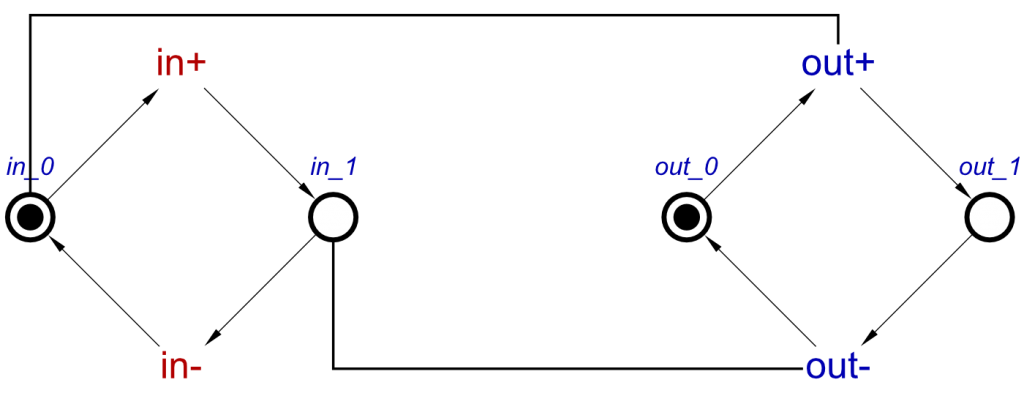

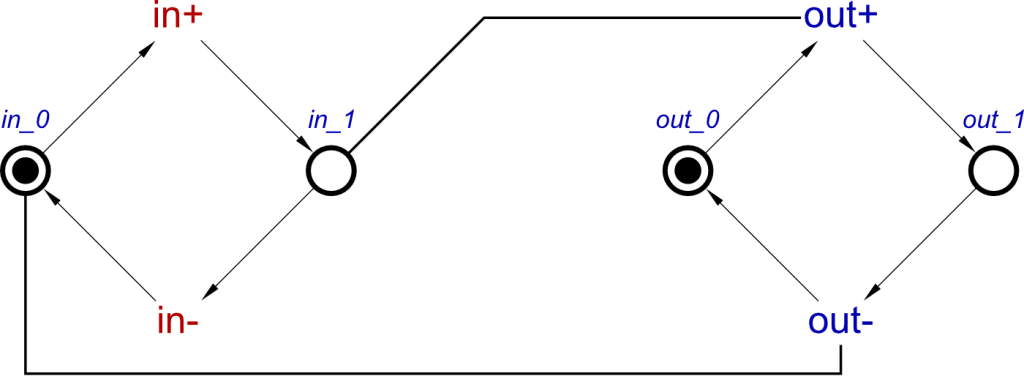

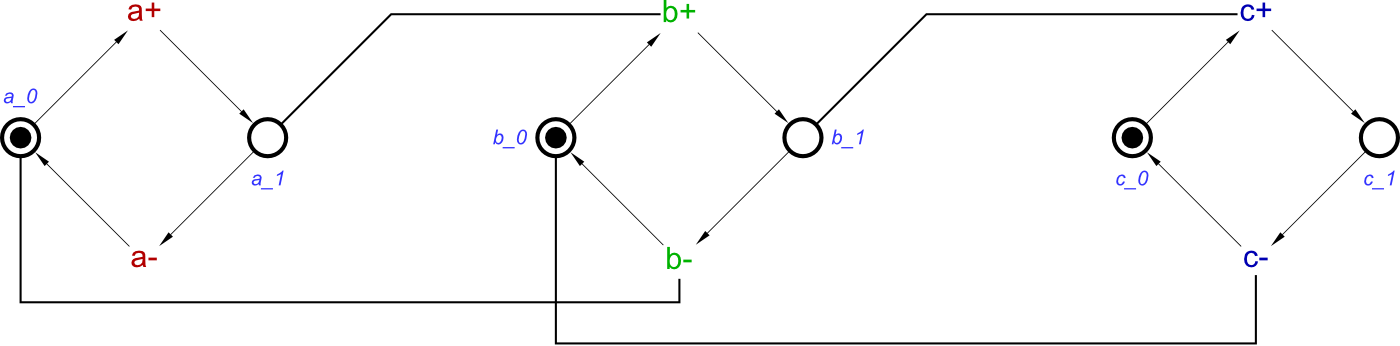

A full example – 2 OR gates

Now we have discussed OR-causality, and the algorithm for this, let’s do an example from start to end, 2 OR gates. In this example, signals a, b, d and e are inputs, c will be the only output.

The concept for this is:

circuit = orGate a b c <> orGate d e c

Expanded into signal-level concepts, this is:

circuit = [a+, b+] ~|~> c+ ⋄ a- ⇝ c- ⋄ b- ⇝ c- ⋄

[d+, e+] ~|~> c+ ⋄ d- ⇝ c- ⋄ e- ⇝ c-

So, the tool will take these as these lists:

Causes: [a+, b+] & Effect: c+

Causes: [d+, e+] & Effect: c+

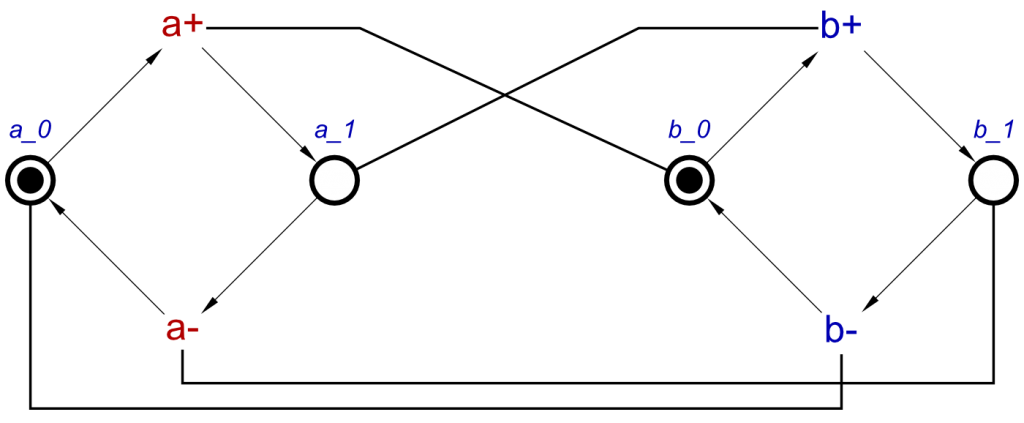

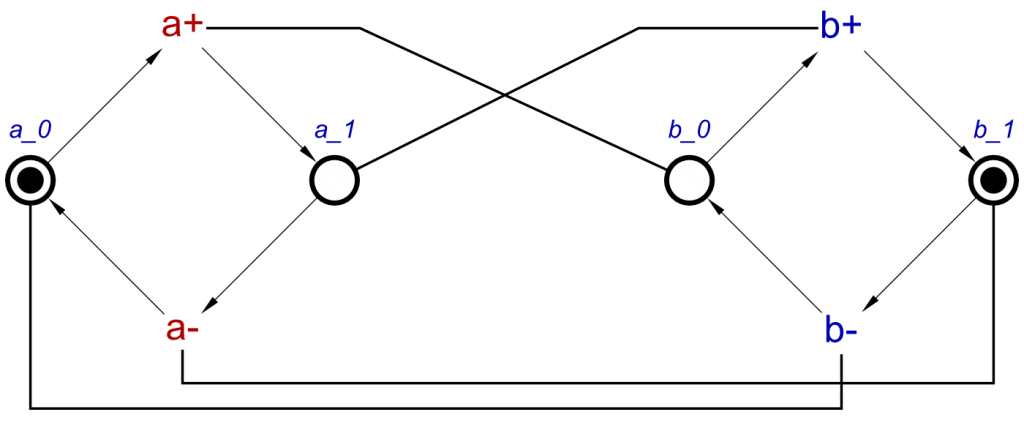

We now perform the Cartesian product on the two causes lists, which, knowing that there are two causes in each list, this will give us 4 c+ transitions. The result, with the transition names included will be:

Causes: [a+, d+] & Effect: [c+]

Causes: [a+, e+] & Effect: [c+/1]

Causes: [b+, d+] & Effect: [c+/2]

Causes: [b+, e+] & Effect: [c+/3]

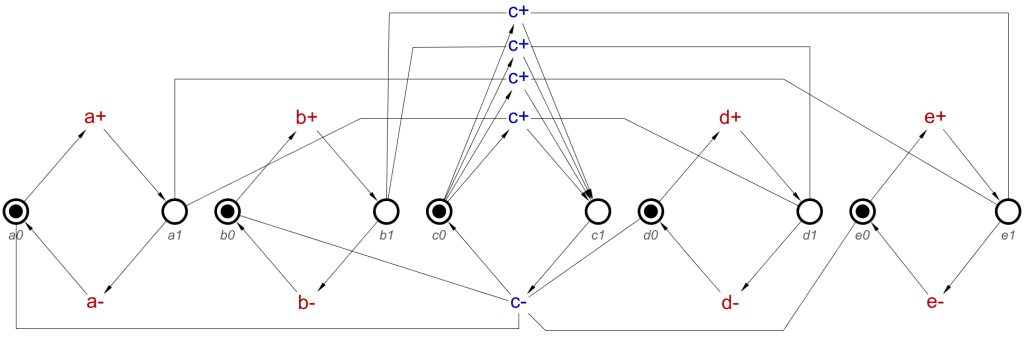

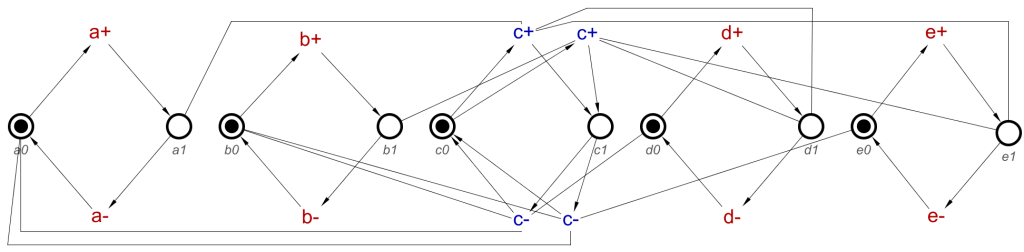

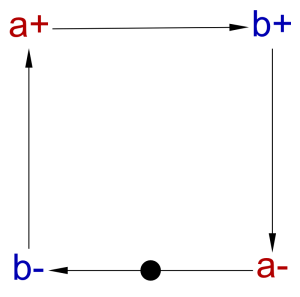

And this will translate to an STG like this:

This clearly has 4 c+ transitions, and testing it proves that for any of them to allow any c+ to occur needs at least one of a+ and b+, as well as, at least one of d+ and e+.

Finally

In both of these parts of the blog post, I have introduced OR-causality, and the algorithm to translate this to STGs. Through several examples, it can be seen that the algorithm works to produce STGs which display OR-causality.

The now released concepts translation tool can be effectively used to specify circuits with many functions, and the inclusion of OR-causality makes this better still.

The future of this blog series will include some concepts used in the translation process to specify signal types and initial states, which in turn serve as somewhat of a tutorial for the tool.

The tool is now available from https://github.com/tuura/concepts, which includes a manual to help with installation. It is also integrated with the STG plugin of Workcraft, and is included with a download of the latest version of Workcraft.