Key themes: transubstantiation; stage violence versus real violence; crucifixion tableau; production and staging.

I think that we studied this play because its use of transubstantiation blurs the boundaries between acting and reality. I have learnt that the transubstantiation of the host would hold the same significance for both the world of (an increasingly Christian) audience after the Edict of Expulsion in 1290, and the world of the play itself. In both the audience’s reality and the play’s representation of its own reality, only the appearance of bread remains after the host has been consecrated as transubstantiation relies on the complete conviction that the bread has been converted into the body and blood of Christ. Therefore, the real and unreal blur in this unique scenario where theatricality relies on illusions that transubstantiation refuses. Where the host-as-prop holds an immutable significance in the audience’s reality, the actors’ staged reality demands a suspension of these beliefs. There is a problematic assertion of actual violence on the consecrated body of Christ through the staged violence on this particular ‘prop’. An example of such violence can be found in the tableau of the crucifixion between lines 504-516 where the host, attached to Jonathas’ hand, is nailed to a post [1]:

The text does not make it immediately evident how “a poste” becomes available on-stage for Jonathas to nail the host to, neither does it describe the effort to pull Jonathas free.

The Oxford production (2013), directed by Elisabeth Dutton, staged this tableau by ‘nailing’ the false hand to another character’s hand [2]. This allows whichever actor that is chosen to supplement the dismemberment of Jonathas’ hand to also use their body to signify the crucifix:

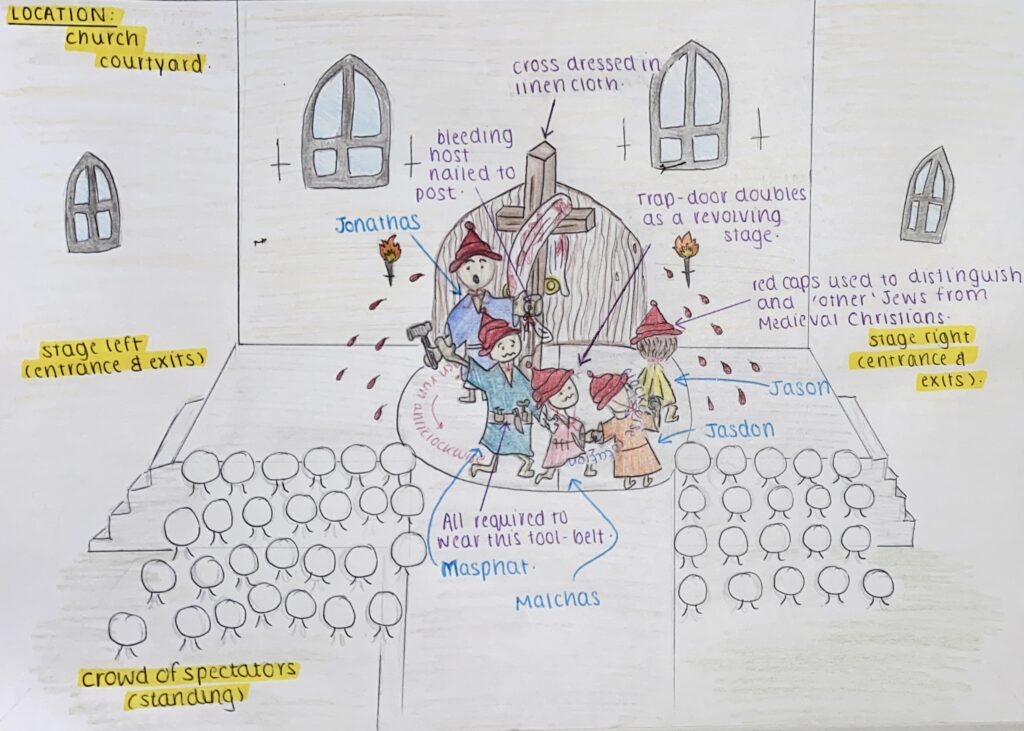

I would stage this tableau slightly differently. I like the Oxford production’s use of a religious space for the set. However, I would install a stage in a Church courtyard to maintain the outdoor tradition of plaice and scaffold theatre whilst also preserving the impression that a Christian space has been infiltrated.

I would also have the audience standing so that there is a collusion between Jonathas, Masphat, Malchus, Jasdon, Jason, and the audience. The ability of the audience to practically be on-stage themselves, whilst the actors also have the ability to enter from within the crowd of spectators and frequently re-join them, provides ample opportunity for audience interaction with the actors. This introduces the opportunity to create the illusion that they, too, have conspired to produce what happens on-stage.

I would propose that there is a trap door incorporated into a revolving stage. A crucifix stands in for the post and will ascend through the trap doors in parts that the team on-stage will assemble in front of the audience with the toolbelts that they wear. A cloth soaked in the blood of the host from the previous action will be draped over, to make the symbolism immediately clear. My concept for this piece follows:

A revolving stage with a runway would also be used to exploit the potential of this scene’s physicality where Jonathas would be pulled anti-clockwise, against the turn of the revolving stage to emphasise the force with which his body is tugged, shaping attention around the power of Christ and the cross to combat their strength. The actors could also make use of the stage space by flinging their bodies down the runway to complement the exertion of their strength on the fake hand.

I think the only way to resolve this difficulty of the play’s violence is to emphasise how the priest sanctifies the host before the play begins: the unperceived pre-history of the object can then introduce doubt as to whether this host in particular is the true embodiment of Christ or a ‘sanctified’ stage-Christ.

[1] Sebastian, John, editor. Croxton Play of the Sacrament. Medieval Institute Publications, 2012, https://d.lib.rochester.edu/teams/publication/sebastian-croxton-play-of-the-sacrament, Accessed 23 May 2022.

[2] Dutton, Elisabeth, dir. The Croxton Play of the Sacrament, Oxford, 2013.