Key Themes: play-text versus performance; The Rose playhouse; forbidden knowledge

Studying Doctor Faustus has prompted me to re-examine how much agency we should give to a play-text. Until this week, I have felt like these texts are ‘finished’ in the same way that novels or poems are. However, the disparity between the A-text and the B-text of Doctor Faustus has heightened my awareness of the temporality of theatrical performance where what is captured on the page of the play-text can only be a benchmark for what is enacted on-stage. Plays exist only in the moment that they are performed, so play-texts can only try and capture these moments that are designed to be experienced, not read. If the text is merely a starting framework for performance as a necessarily collaborative art form, then there is no such thing as a ‘finished’ play-text. On reflection, I think this is a good thing because it encourages individual interpretation that leads to more varied productions through the creative freedom it inspires which, in turn, will provide us with a more comprehensive production history of Faustus to draw from, giving us different ways of examining his character.

Although the A-text (performed in the later 1580s at the Rose playhouse) may be closer to Marlowe’s own vision for the play, the later B-text of 1602 is an invaluable addition because it contributes to a kaleidoscopic image of Faustus’ character in performance, paving the way for other creatives to examine his character through a different lens. The result would be a wealth of material to draw from which, side by side, a comprehensive study of Faustus which is at once sympathetic and condemnable, fated to sin yet alluringly redeemable, spirit and human, would be amalgamated to reflect his complexity.

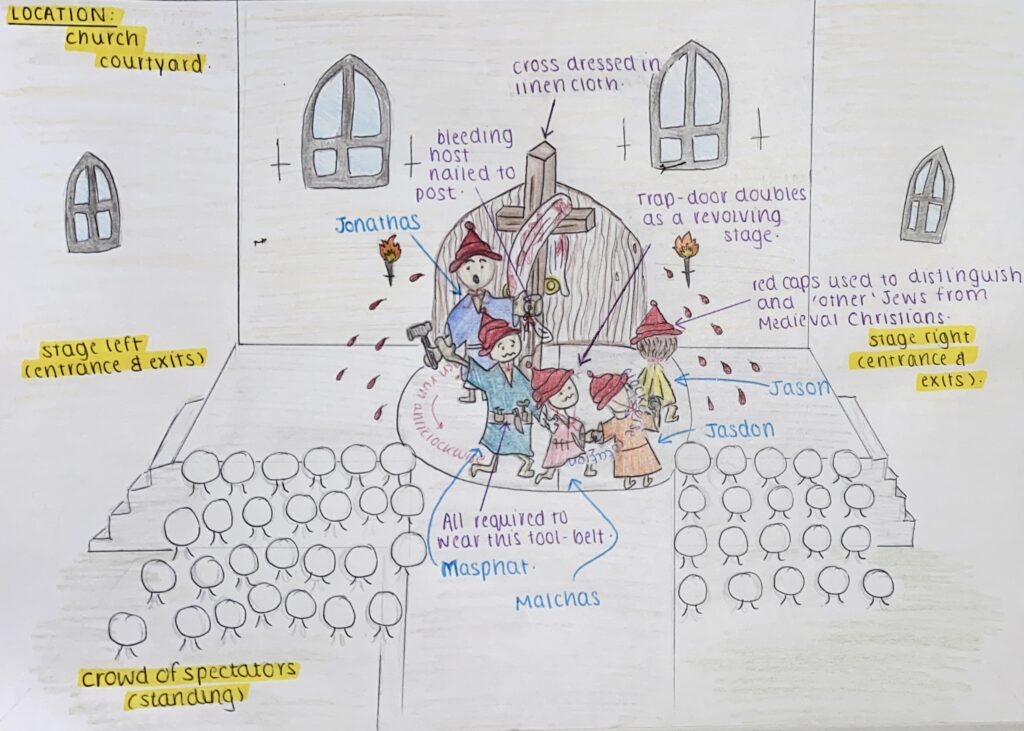

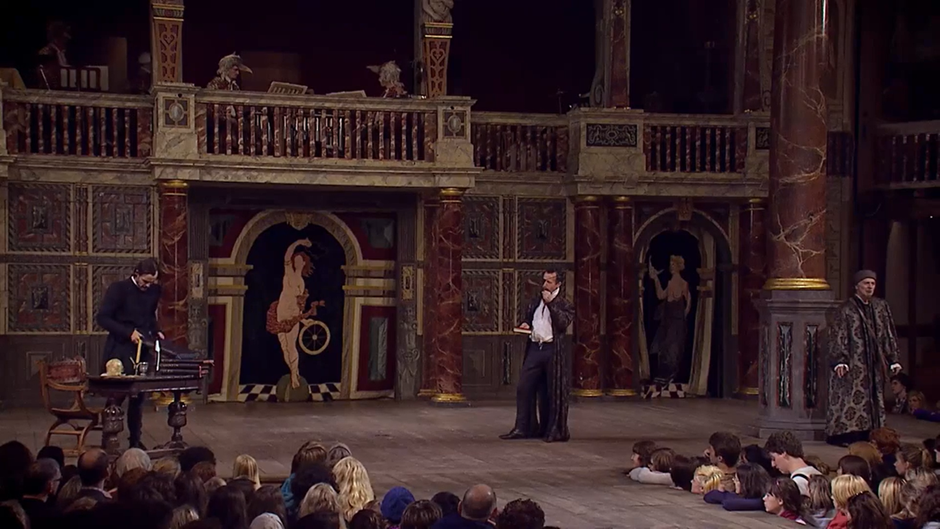

In light of these reflections, I have produced a design for the painted cloths that were typically used to adorn The Rose playhouse stage. Typically, they were decorated with biblical, mythological, or allegorical scenes, shaping the audience’s interpretation of the play by visually depicting its central themes (00:09:59-00:10:12) [1]. The Globe’s 2016 production of Doctor Faustus uses the central tapestry to depict the goddess Fortuna, her wheel of fortune acting as the symbol of the B-text’s Calvinist insistence on Faustus’ immutable, fated damnation [2]:

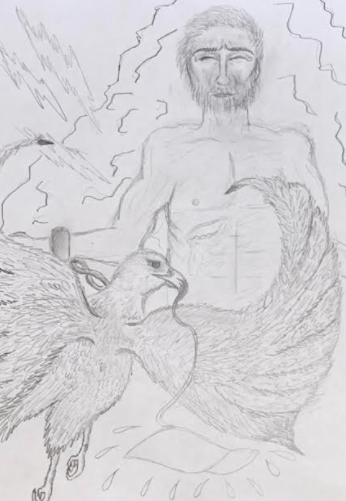

For my tapestry design, I have chosen to depict the myth of Prometheus:

By anticipating many further ‘conflated’ productions of Faustus that merge the A and B texts, my tapestry accommodates a ‘liminal’ Faustus who is at once both a figure of pity and damnation. Like Faustus, Prometheus is a multifaceted scholar: on the one hand, he steals fire from the gods to create life, betraying them, but on the other, he shares his superpower with humankind. Whilst his betrayal of the gods to seek forbidden knowledge seals his fate, whether Prometheus is a martyr or a traitor is up to us – an association that, through this tapestry, the audience of Faustus would be interrogated with and demanded to answer according to their own interpretation of Faustus.

[1] Clegg, Roger and Eric Tatham. “4. The Rose playhouse, Phase 1 (1587-1591/2).” Reconstructing the Rose: 3D Computer Modelling Philip Henslowe’s Playhouse. De Montfort University, 2019, <https://reconstructingtherose.tome.press/chapter/the-rose-playhouse-phase-i-1587-1591-2/>[last accessed 23/03/22].

[2] Marlowe Christopher. “Doctor Faustus”, Globe on Screen, Shakespeare’s Globe on Screen (2008-2015). Drama Online. <https://www.dramaonlinelibrary.com/video?docid=do-9781350996786&tocid=do-9781350996786_4598127137001> [last accessed 23/03/22].