Mini Project 2: GIS Mapping Analysis

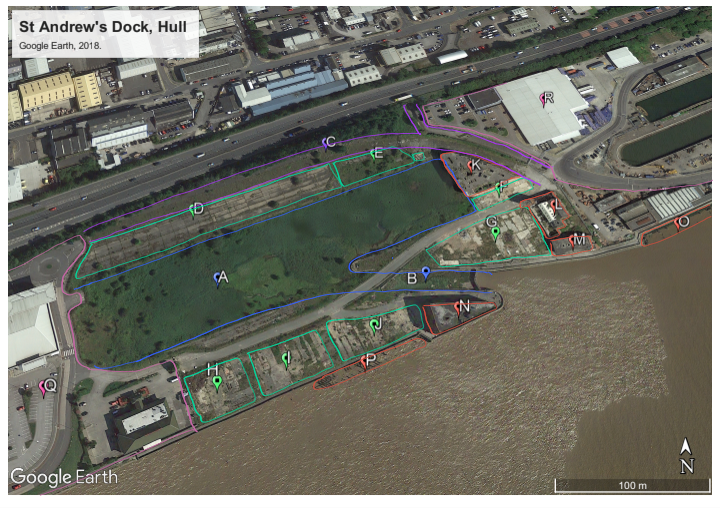

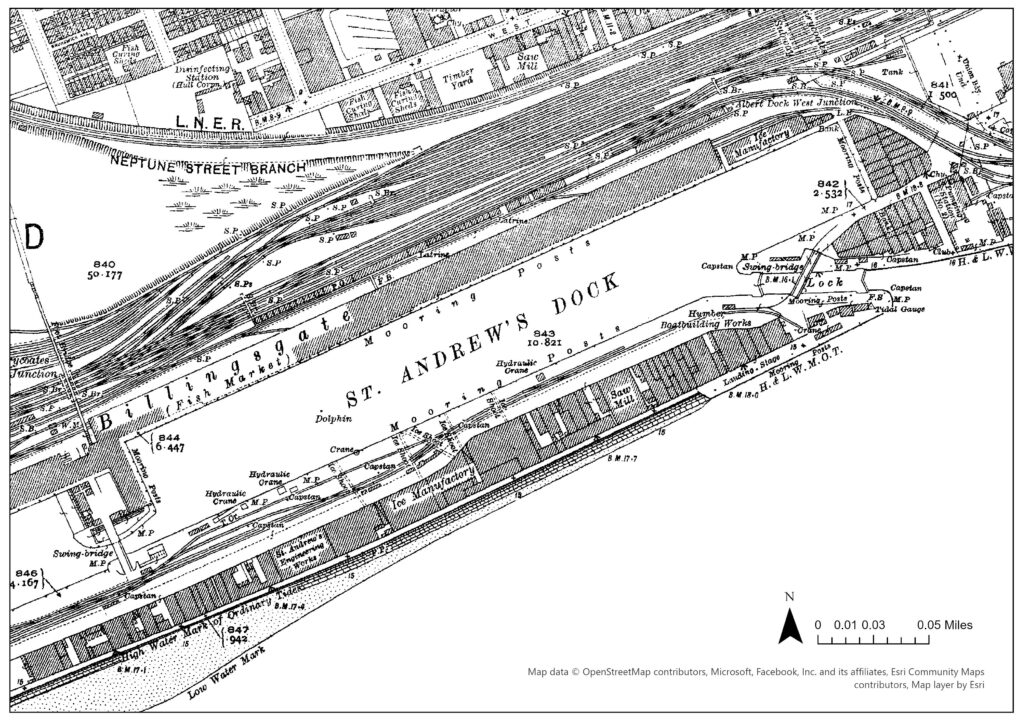

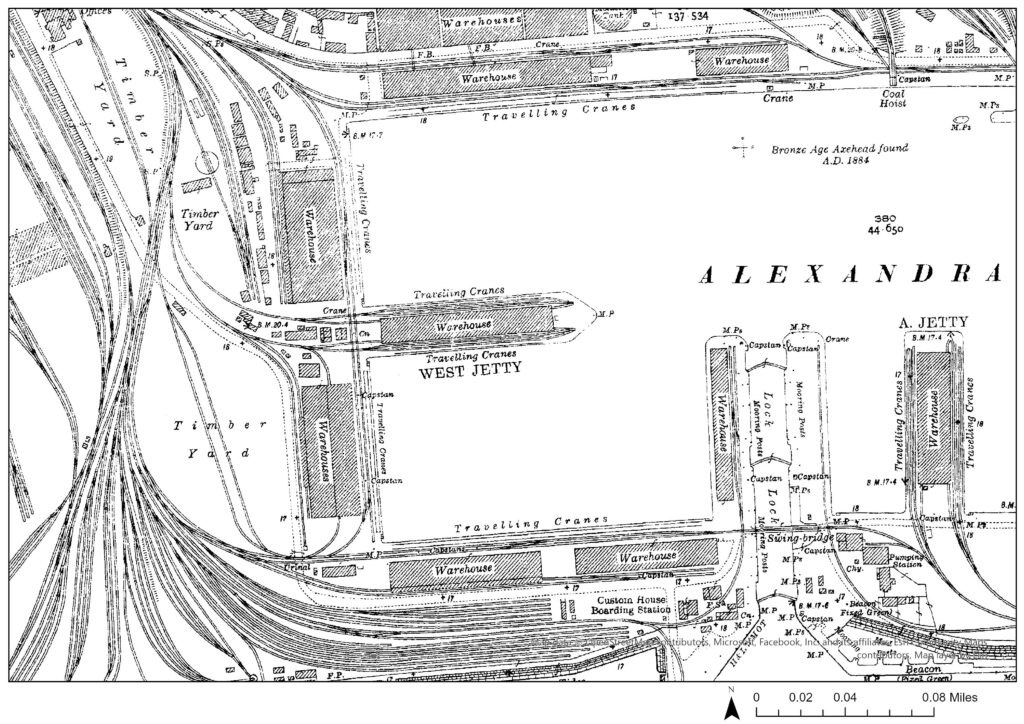

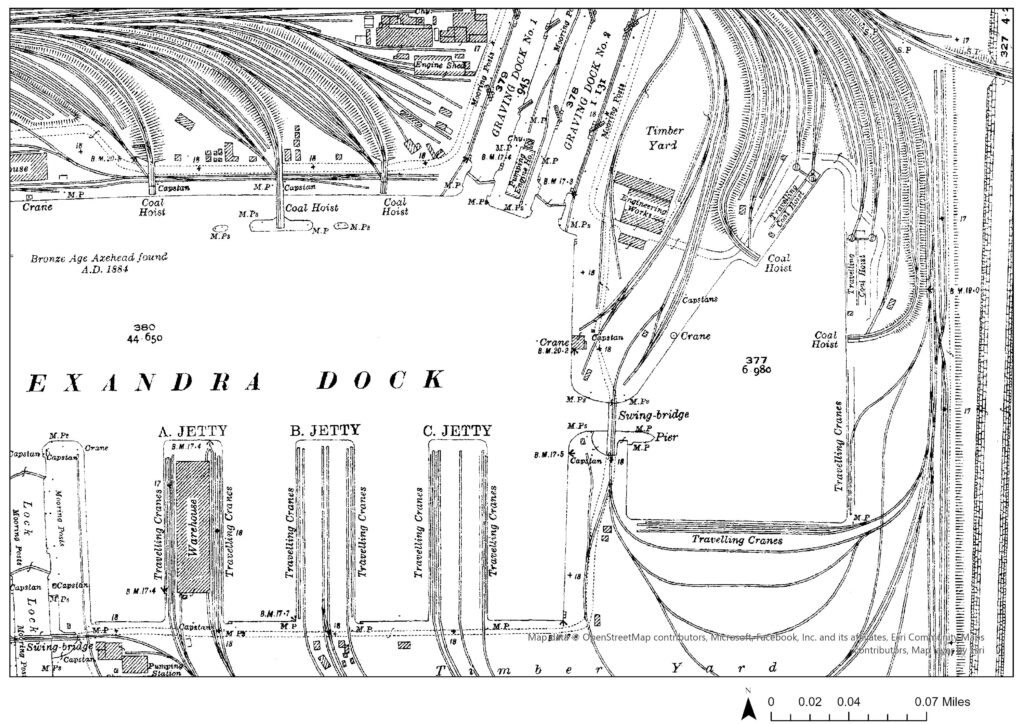

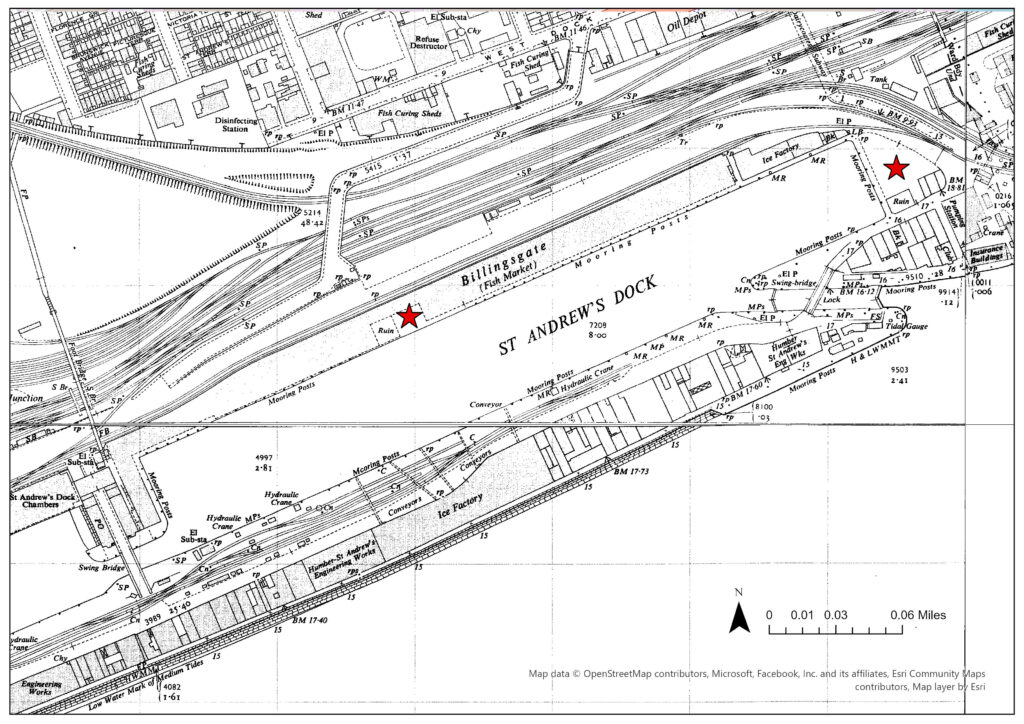

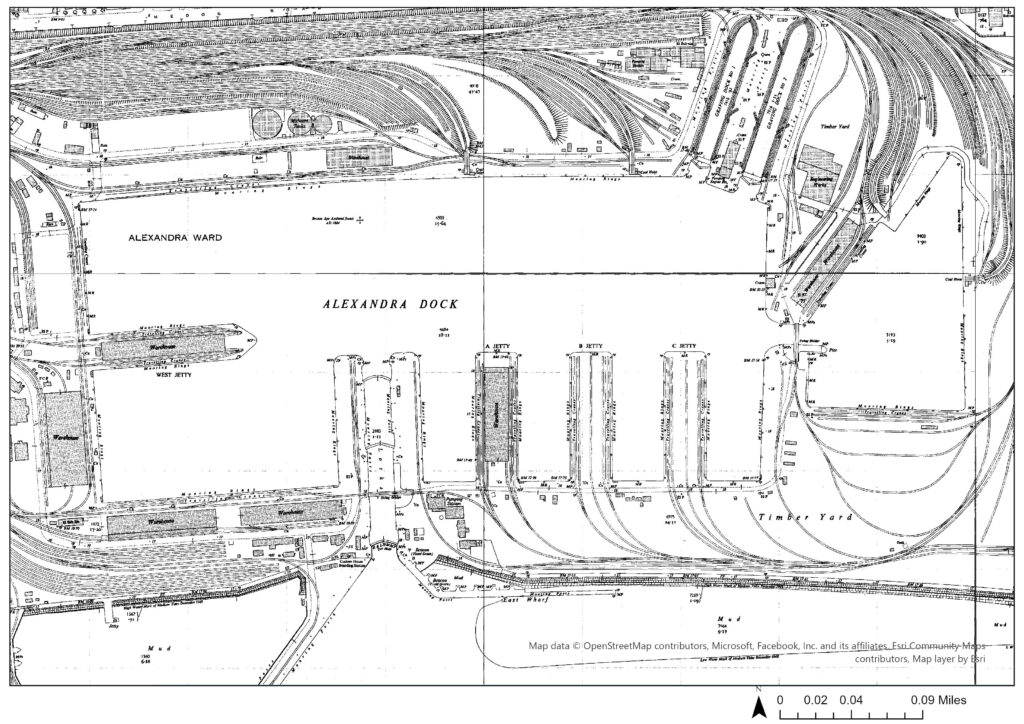

Within Hull’s heritage, that being the history actively remembered and considered culturally valuable by the community, the fishing industry is typically championed.[1] One visual iteration of this is the number of memorials and monuments across the city dedicated to trawlermen and the wider fishing community. Heavy casualties amongst fishermen naturally left remnant feelings of loss and sacrifice, which increased its significance in terms of heritage. A more varied maritime history, however, brought prosperity and status to the port of Hull but is seldom regarded with the same importance. For comparison, St Andrew’s Dock and Alexandra Dock were both built in the 1880s, with the former dedicated to landing fish and the latter holding more varied trade, including timber and coal.[2] Alexandra Dock (Figures: 2&3) had significantly more investment in infrastructure than St Andrew’s (Figure: 1), as can be seen through the disparity in dockside technology such as number of cranes and railway lines, suggesting it was more prosperous.

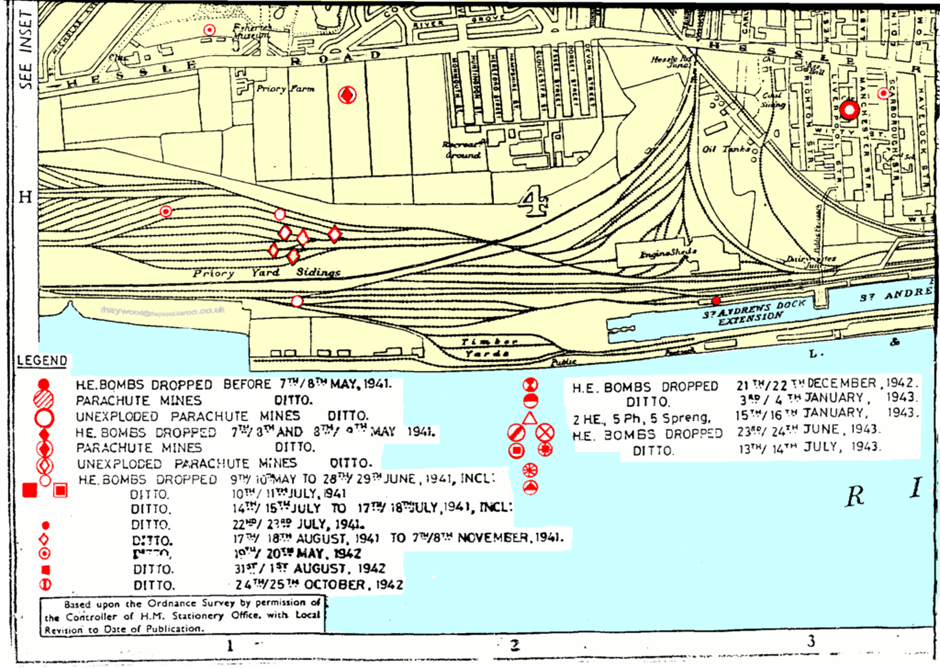

Further to this, considering the docks were strategic targets for Axis bombing campaigns during WWII, Alexandra Dock was much more heavily affected than St Andrew’s. Figures 4-7 show the locations of all High-explosive and Parachute Mines dropped on the city.[3] Alexandra had upward of twenty-five direct hits, with many more in proximity (Figures: 6&7), compared to just four on St Andrew’s and its extension (Figures: 4&5). As such the trade activity of Alexandra Dock was inferably of larger importance than that of St Andrew’s, and thus a more significant target for bombers, as its coal and timber, for example, were vital to continuing domestic industry and the wider Allied war effort. Moreover, Figure 9 (when compared with Figures: 2&3) shows all but the warehousing on the northwest corner of Alexandra Dock was rebuilt in the decade after the war, compared to St Andrew’s where the three areas hit by bombs on the main dock were still labelled as ‘ruin’ (see stars on Figure 8) indicating a lack of investment in rebuilding efforts.

[1] Rodney Harrison, “What is Heritage?” in Understanding the Politics of Heritage, ed. Rodney Harrison (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2010), 9.

[2] David Gerrard, A Century of Hull: Events, People and Places over the 20th Century (Stroud: The History Press, 2009), 13.

[3] Rob Haywood, “The Hull Blitz: A Bombing Map,” RHaywood, accessed on 3 January 2024, http://www.rhaywood.karoo.net/bombmap.htm.

Originally plotted c.1945 but digitised by Haywood, a local historian. Incendiary bombs were not included. Points referenced in Map Analysis were cross-referenced with Nick Cooper, City on Fire: Kingston upon Hull 1939-45 (Stroud: Amberley Publishing, 2017), 81-88.