Background

This post is inspired by a tweet I saw a few weeks ago where @TZbirder had queried why a publication on African Elephant poaching had no African authors. I wanted to know how common this was, so I decided to look at authorship of papers in a Journal that I know is focused exclusively on Africa (and is close to my heart as it was where I got my first paper published). I downloaded the bibliographic records of the last 2000 African Journal of Ecology papers from Scopus to look at the authorship in relation to the country listed in each authors affiliation. I assumed that the key authorship positions were “First” and “Last” author and focused on these two positions predominately. It is important to note I can only look at the institutional address of the authors so there will be (I have no doubt) some authors of African origin in European institutions and visa versa (as I myself have been on several occasions).

I make use of the R packages bibliometrix, tidyverse, igraph, stringi and ggnetwork and I have made extensive use of https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/bibliometrix/vignettes/bibliometri x-vignette.html.

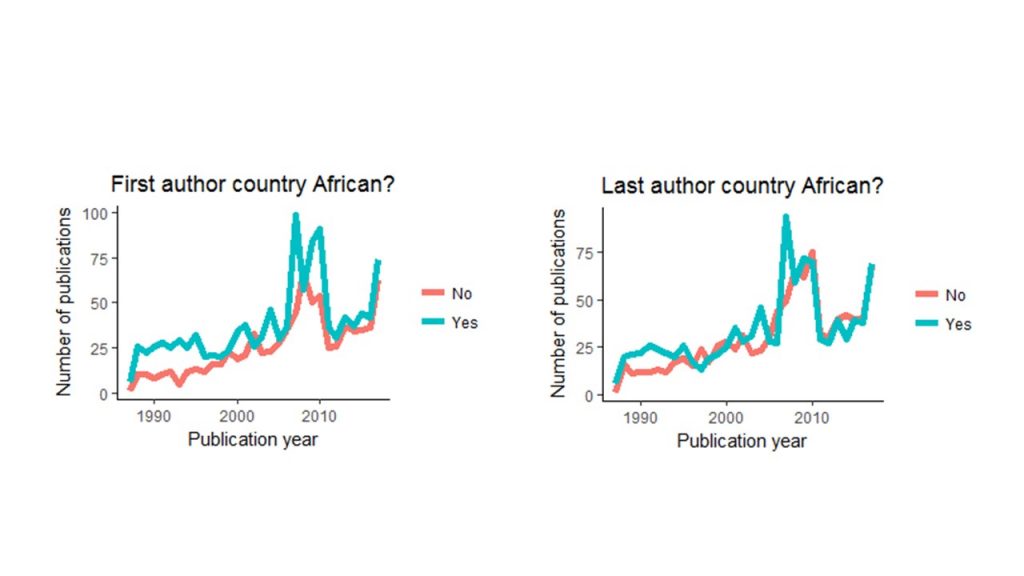

Trends in first and last authorship

The number of publications from an Africa-based first author compared to a non-Africa based first author appear similar – both are increasing steadily which can only be good news. The trends in last authorship are similar to those in first authorship. A general increase in the number of publications regardless of Institutional country.

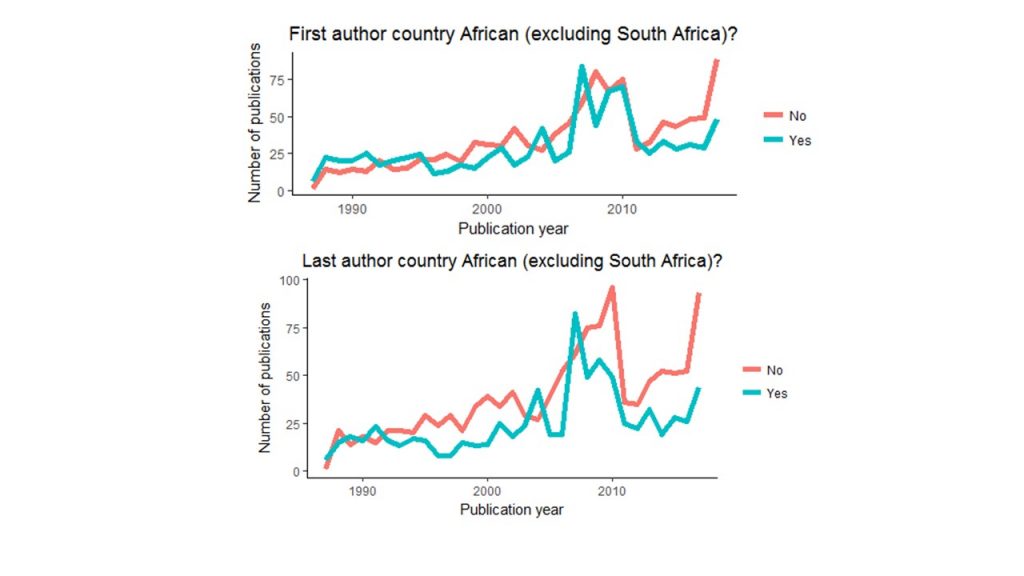

What happens when we exclude South Africa?

Again, the trends are similar but there are consistently more non-Africa based last authors than African-based ones – although the number and trend are similar, but with a more recent large difference becoming apparent.

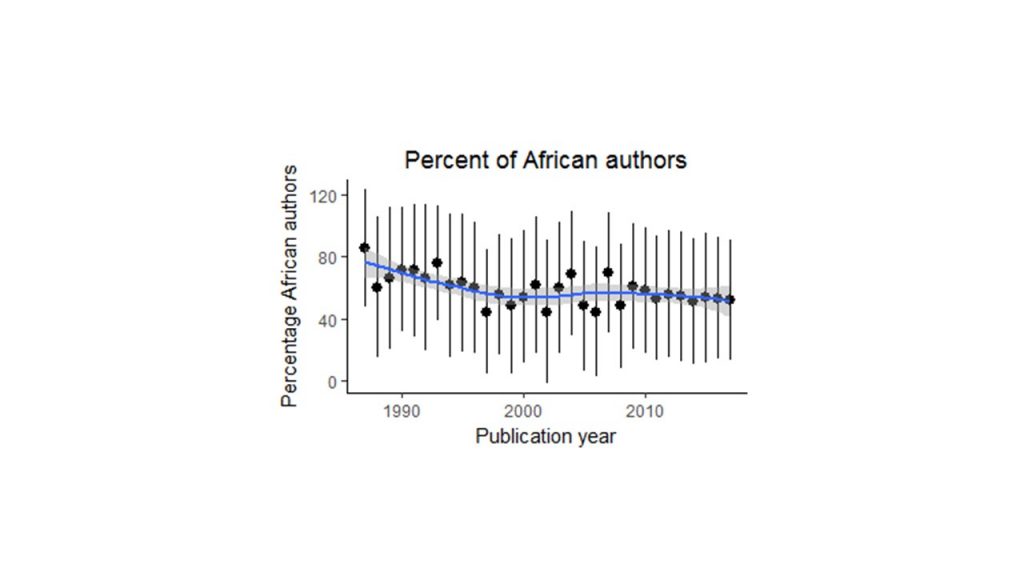

What about the percentage of all authors who are from African Institutions?

Interestingly there seems to be a (very) slight decrease in the percentage contribution to publications in the African Journal of Ecology by Africa-based authors overall. However, most years have more than 50% of authors being based in Africa. The apparent decline perhaps reflects the widening of interest in the journal rather than a decrease in the opportunities for Africa-based authors.

Interestingly there seems to be a (very) slight decrease in the percentage contribution to publications in the African Journal of Ecology by Africa-based authors overall. However, most years have more than 50% of authors being based in Africa. The apparent decline perhaps reflects the widening of interest in the journal rather than a decrease in the opportunities for Africa-based authors.

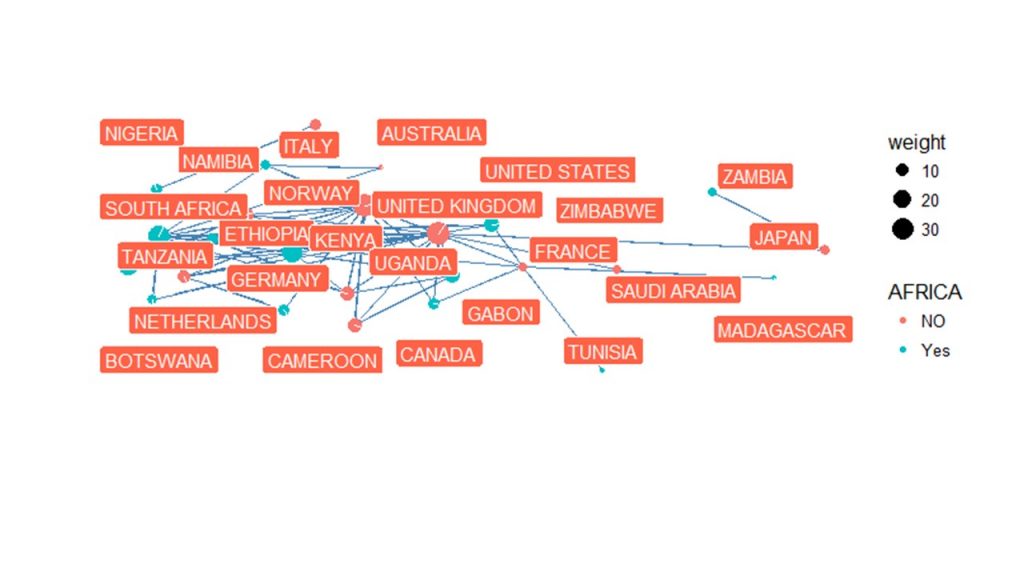

Let’s look at country collaborations

The main countries collaborating with others are the USA and UK with South Africa, Uganda and Tanzania the main African countries.

What about changes over time?

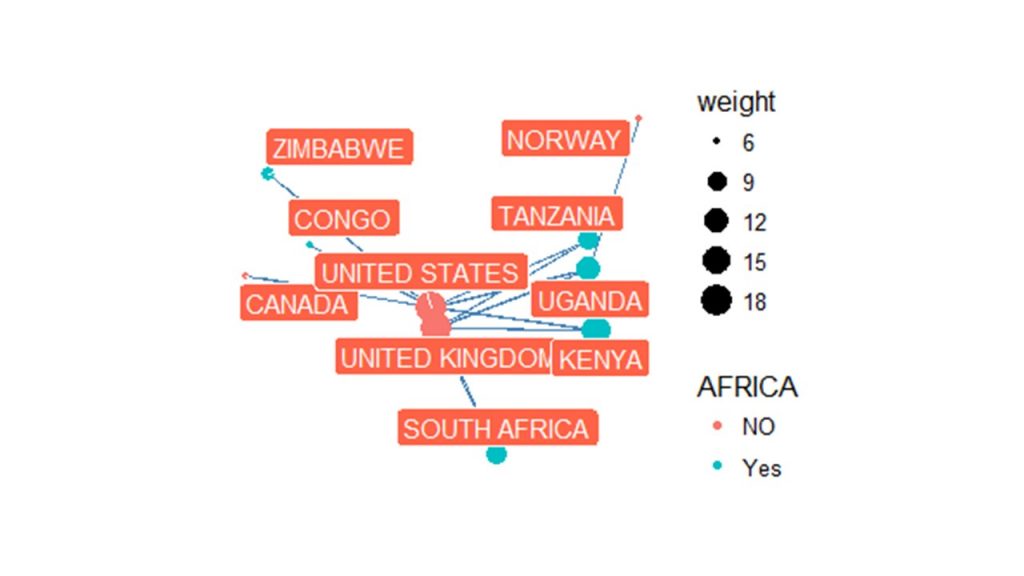

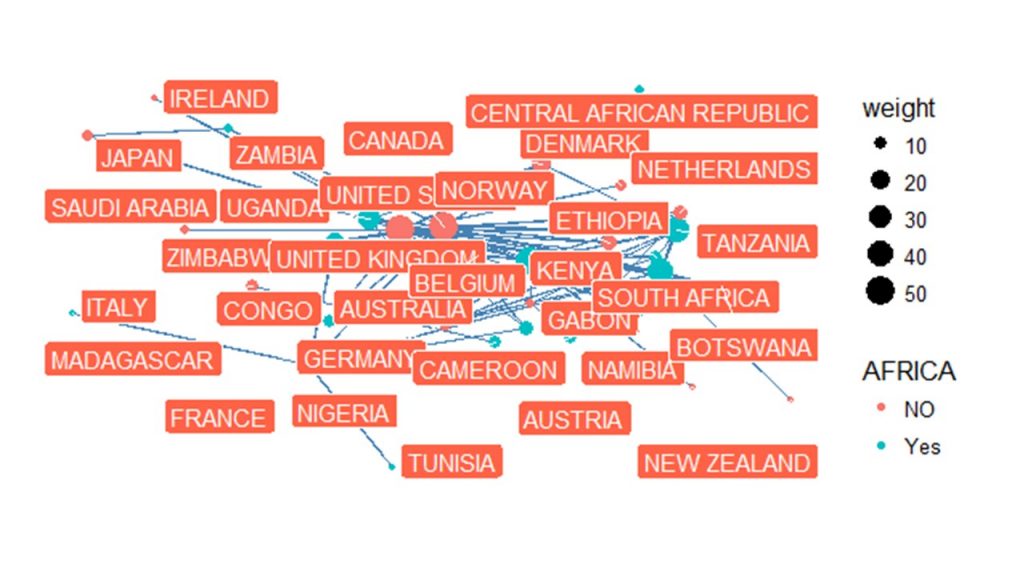

I split the data in to two groups – pre 2006 and post 2006 to see if there has been any change in patterns of country collaboration

Pre 2006

Post 2006

Pre-2006 the UK and USA dominate the collaborations, post-2006 collaborations included more African countries with South Africa, Kenya and Tanzania being predominant. The UK and USA still dominate though. West Africa is under-represented, perhaps due to the history of the African Journal of Ecology, which has its foundations in East Africa. There is a greater diversity of Institutions involved in Research in to African ecology than there was in the past.

Pre-2006 the UK and USA dominate the collaborations, post-2006 collaborations included more African countries with South Africa, Kenya and Tanzania being predominant. The UK and USA still dominate though. West Africa is under-represented, perhaps due to the history of the African Journal of Ecology, which has its foundations in East Africa. There is a greater diversity of Institutions involved in Research in to African ecology than there was in the past.

Conclusion

From this cursory look there is indications that for the African Journal of Ecology capacity building is a continued focus of the journal. We can only hope that in the near future more Africa-based researchers are leading the collaborations with other institutions across the world.