I’ve been living out of my suitcase for the past 10 months now researching the various people and sites that govern Nepali (and the broader global South) workforces into the private security industry. In fact, my academic work to date has focused largely on how labour is organised and managed in the production of global security and how we produce knowledge about security experts/professionalism and value,with specific focus on the private security industry and Gurkhas. This research include location sites of Afghanistan, UAE, Qatar, UK and Nepal. It also comprises of interviews with security professionals/practitioners (defined by the security industry as highly skilled management and low skilled global South workforces), security company directors, global recruitment companies, local manpower providers (in Nepal), government officials, labour activists, academics and security migrant families.

a post interview photo with Hindi (pseudonym), a wife of a foreign security worker in Qatar. She has not seen her husband is 1.5 years and is looking forward to his 1 month off in 6 months time. They have one daughter who is 2 years old and she lives with her family in Jhapa district, Nepal.

Below is a brief (and developing) visual ethnography of the different people and places that make up global security migration. This particular post mainly focuses on recruitment processes and pathways young Nepali men (and sometimes women) venture through in becoming foreign security workers–be it Gurkhas or unarmed security contractors. In both cases, the motivations are largely centred around unequal economic geographies and the hopes and militarised fantasies of what foreign security work can offer them and their families.

a Gurkha training centre billboard in Kathmandu. Recruitment advertisements like these are littered throughout cities in Nepal.

This recruitment poster to the left is from a company who has only been operating for 2 years. Training centres and recruitment images such as this one are scattered throughout the cities of Nepal. I managed to talk to some of the training centre recruits in Kathmandu, Pokhara and Dharan. Most of the recruits pay 30-40 thousand Nepali Rupees for their preparation training. This includes physical fitness, english and math skills and interview preparations.

Sameer, a recruit with a Kathmandu based training centre, comes from a village in Kathmandu Valley and knew nothing of Gurkhas until he moved to Kathmandu. Captivated my the militarised masculine imaginings depicted in the training centre advertisement image, and the financial and social mobility becoming a Gurkha could bring, he asked his parents for the money needed to take the training course.

Gurkha training centre recruits finishing up their morning physical fitness. It starts with a 5am run and is followed by a series of static strength tests.

This image to the right is of young Nepali men from a Kathmandu based Gurkha training centre. There are 50 of these young men registered now but as August approaches, and the annual recruitment for the British army begins to take place, more than 200 recruits will come to this particular training centre.

In total, there is an estimate of 12-14 thousand young men that try out for the British Army and Singaporean Police every year. On average, only 600 men are accepted. When I presented these odds to the potential recruits I talked to, and asking them what makes a man successful at becoming a Gurkha, I was repeatedly told: hard work, dedication and luck. Most recruits had no back up plan if they were not successful.

Talking to young Nepali men in Dharan who registered with one of the local Gurkha recruitment training centres. They are in their English class and practicing their language skills as I ask them questions.

Becoming a Gurkha is rooted in a long tradition in Nepal of over 200 years of military service with the British (and Indian) armies. If successful, these men have a chance to significantly uplift their families out of poverty and substantially increase the material possibilities for themselves and their local communities. The stake are very high.

What I found striking when talking to these very young men is that their desire to be a Gurkha was not for general militarised imaginings of army life. In fact, most did not have any detailed understanding of what the day-to-day military life would be like. Instead, they repeated told me they wanted to be Gurkhas for the life opportunities being located in Britain (and Singapore) could offer them and their families. Recruitment into the British and Indian Armies and Singaporean Police as Gurkhas is still very much a man’s journey.

a photo of young Nepali women who successfully completed preparation training with a Gurkha training centre in Pokhara

In 2007 the British army did trial a pilot programme designed to encourage Nepali women to try out. However this initiative was abandoned and, after talking to numerous stakeholders in Nepal, no official explanation was given. This was particularly disappointing to the many women who had trained for months in preparation for this opportunity that historically has only been open to men.

one manpower company out of the currently 841 registered companies who operate in Nepal. Not all provide opportunities to work in foreign security.

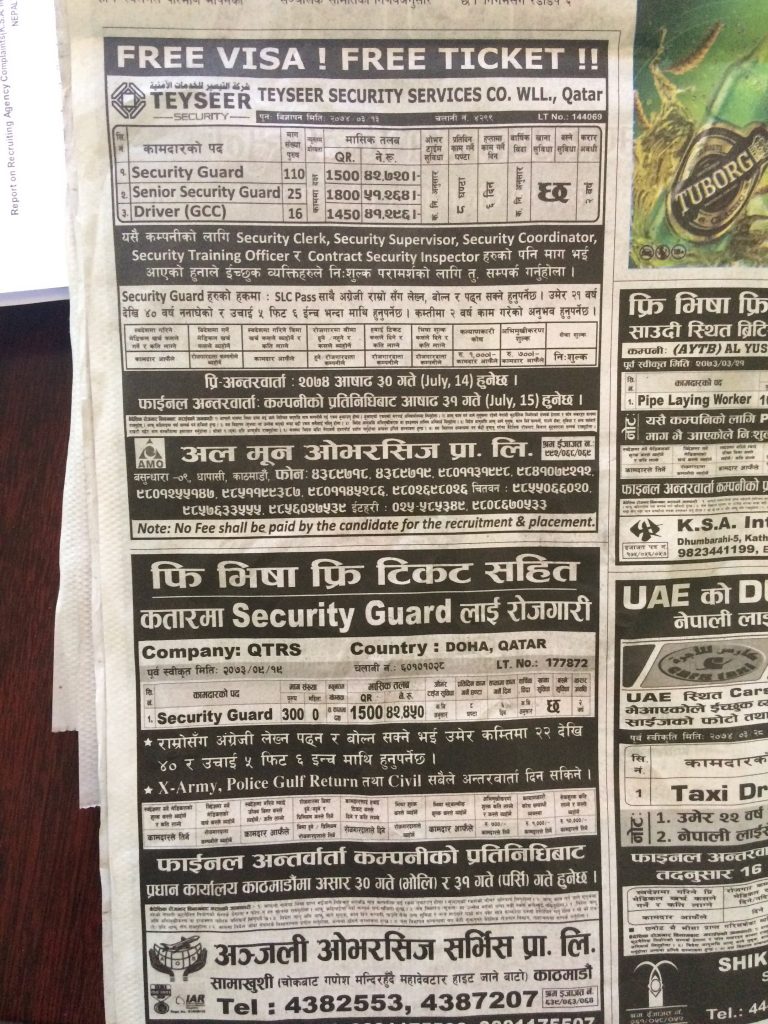

Of course foreign service with the British and Indian Armies and the Singaporean police are just one route out of poverty and increasingly material status. Nepali men (and now sometimes women) are venturing into foreign security work in the unarmed security industry. The pathway to this security work is through manpower providers. These providers act as the gatekeepers for foreign security companies accessing Nepali labour. To the left is an image of one such manpower company’s office, who recruits into Saudi and Qatar. Nepali unarmed security workforces generally travel to Malaysia, Qatar, UAE and Saudi for security work.

Achieving foreign security employment into the unarmed industry brings with it different challenges than armed security. Much of the discussion about labour violations, human rights violations, long work hours and poor working conditions of other global industries are certainly echoed in unarmed security.

Ganga (pseudonym) and his family in Itihari. Photo taken in front of their home. Ganga works in Afghanistan as a security contractor.

The pathways into foreign private security work are vastly different depending on whether you qualify for armed security or unarmed security. Armed security continues to privilege men who have former military and police service, generally as Gurkhas who have served in foreign militaries. However, the increased permanent migration of retired British Gurkhas to the UK, after their right to settle was granted, has opened up private security opportunities to Indian army retired Gurkhas and Nepal army retired soldiers.

Ganga is one such man who qualified for armed security work. I met with Ganga and his family in Eastern Nepal. Ganga has an extended family now that he has to look after since his brother passed away and there was no one else to take care of his brother’s children. As usual in the motivations to work in conflict zones, retired Gurkhas often feel compelled for financial motivations. When they retire from military service, their children are generally in higher education which costs a significant amount. To maintain their lifestyle they transition into private security work.

Ganga works in Afghanistan as a security contractor. He is a retired Indian army Gurkha who has been working in private security for the past 6 years. His security income, along with his army pension, pays for his children’s education and household expenditures. Because of the extended family, Ganga and his wife cannot afford to save much and their are still working though how they will afford retirement, when Ganga can no longer work in the private industry.

Ritesh (pseudonym) working as access control for a facility in Qatar

Ritesh (photo to the left), was recruited into the unarmed security industry while in Kathmandu undertaking a degree at the local university. He, like all of the other cohorts of his I interviewed in Qatar, paid a considerable amount of money to recruitment agents and a local broker in order to obtain security work in Qatar.

Migrants paying significant amounts for foreign work is common practice despite Nepali and Qatar laws the prohibit excessive amounts being charged to migrants. Ritesh’s parents helped finance the fees necessary for him to work overseas. Unlike Ganga, Ritesh only needed to speak English, be a minimum of 5 feet, 8 inches in height, and have a good level of physical fitness.

As far as accessing foreign work goes, Ritesh is rather lucky. While he and his family had to pay a hefty amount for foreign work, he managed to land a fairly good contract in Qatar. His salary, good working conditions and regular training are in part because of the client’s particular labour standards demanded as a contractual condition, and the ad hoc, and unpaid, regular training he receives by his direct manager. Because of this, Ritesh is content with his work. The finances he receives is able to help him save to build a house back home in Nepal and hopefully make him financially suitable for marriage.

I was fortunate enough to meet with his parents. They were frustrated with the amount they had to pay to facilitate his overseas work but felt they could at least hold the local broker accountable should anything bad happen to Ritesh overseas. Knowing the terrible work experiences, which include bonded labour and visa confiscation amongst other issues, that plague many foreign workers, they are comforted to hear about Ritesh’s work conditions. His mom expressed particular relief. This does not mean that Ritesh has an easy job. it is hard work and he has little time for leisure. He works 6 days a week and on his day off he mostly sleeps. The labour camp he lives in, while very good in comparison to others, if far from the city centre and getting into the city to explore Doha is expensive.

advertisement for unarmed security contracting work In Qatar. While the one caption reads: free visa, free ticket, this rarely happens in practice.

This post is just a small glimpse into Nepali labour recruitment into the global security industry. In the next blog post I will explore more about the process from other key actors who shape the broader governing practices of foreign security labour management.