Guest Blog post by Dr. Hanna Ketola

I am very excited to join the ‘Military to Market’ project as a Research Associate. My own curiosities with conflict, gender and (in)secure economies resonate with Amanda’s work.

In this blog post I offer glimpses into my own ethnographic research that explores women’s political agency in the context of peacebuilding in Nepal and how this research compliments in many ways the work Amanda is doing for the project “Military to Market”.

I see two main lines of connection between my work and the Military to Market project:

- A feminist curiosity about how subjectivities that are supposedly confined to the ‘local’ or the ‘non-political’, e.g. being an ex-PLA fighter or being a family member of a security migrant labourer are in intricate ways connected to global discourses and relations of power, e.g. in the context of peacebuilding or the security industry

- A commitment to unlearning and shaking up entrenched understandings of who and what matters in global politics via drawing on postcolonial theory, e.g. rethinking notions of ‘women’s agency’ or the figure of the ‘security contractor’

What my project is about

My research is about women’s political agency in the context of peacebuilding in Nepal, specifically, about understanding how the post-conflict moment may generate avenues for expressing agency from the margins of power. In my project, I foreground experiences of women who are not at the centre of policy discourses nor authorised to speak and participate as ‘experts’ – women who enter the realm of peacebuilding as ‘target groups’.

My research is about women’s political agency in the context of peacebuilding in Nepal, specifically, about understanding how the post-conflict moment may generate avenues for expressing agency from the margins of power. In my project, I foreground experiences of women who are not at the centre of policy discourses nor authorised to speak and participate as ‘experts’ – women who enter the realm of peacebuilding as ‘target groups’.

I focus on women who fought in the Maoist army and women who lost their husbands during the war and are engaged in a victims’ struggle. I show how women act ‘politically’ in myriad ways that are not reducible to resisting regulatory gender norms or indeed to resisting peacebuilding; how political agency remains ambivalent. It can manifest as a shift towards collective mobilisation as well as a withdrawal from such activities.

My work rethinks how we conceptualise ‘women’s agency’ and ‘subaltern agency’ and intervenes into critical- and feminist literature on peacebuilding and into scholarship on agency within feminist and postcolonial IR.

Two significant practices of politics feature in my interviews with women who had fought in the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) during the decade long conflict (1996-2006).

The Politics of sacrifice and when contribution goes un-recognised

The women I met had spent time in the PLA cantonments that had been set up as part of the peace agreement between the Government of Nepal and the Communist Party of Nepal-Maoist (CPN-M) in 2006. The cantonments were located in strategically important, remote locations, and overseen by the CPN-M with a very limited monitoring role for the UN. Due to the contested nature of the question of army integration and the power struggle between the political parties, the cantonment of the PLA continued for nearly seven years. At the time of our meeting in 2013 the cantonments had been closed approximately a year ago.

The women I met had taken ‘voluntary retirement’ and had started building their lives, often in a completely new location rather than returned to the remote rural districts from where they had first joined the Maoist movement.

Anger, frustration and disappointment towards the party and the ‘leaders’ over how the army integration process had been handled and how the ‘ex-PLA’ had not been ‘provided for’ and had been ‘discarded’ were the underlining themes in every informal conversation.

Rupa who had been a low-level commander during the war and whom I met in Banke explained:

‘When I was wounded, I was making bombs and grenades in the jungle. My leg was bleeding and swelling. They used to carry me to the jungle at morning and fetch me back to village by night. We struggled that much. When I remember those events, the retirement money is nothing.’ (Interview, Rupa, Banke, 29th November, 2013).

Asmita who had joined the Maoist movement through its student wing and had been verified as a combatant in the UN process talked at length about her friends who had been ‘disqualified’ or ‘tagged as minors’.

‘We fought for the nation and its people even though we were not a professional army, we fought the war our way. After the peace the government sent us for verification, that’s okay. But they tagged some of our friends as minors, we didn’t feel good about it at all.’ (Interview, Asmita, Nawalparasi, 23rd May, 2013).

What I explore in my project is how the women who fought in the PLA do not simply ‘shake off’ the political subjectivities they had crafted through experiencing the war as fighters but rather how these identities mould into something new in the post-conflict context. The continuation of these military identities, forged through conflict, also resonates with Amanda’s work on Gurkhas martial race in private security. In both cases, we are compelled to examine the ways in which militarised identities are constructed and reshaped through the broader political structures such as neoliberalism, capitalism and post-conflict economies for which these men and women are situated.

From my research being ‘ex-PLA’ emerges as a way of being political that was characterised by a prior contribution and sacrifice and by grievances around the non-recognition of these by the UN, by the government and most prominently by the leadership of the party. What I found striking was how this form of subjectivity seemed to crystallise during the cantonment time and was expressed through inhabiting the very categories that had been employed by the UN agencies involved in the ‘verification’ and ‘rehabilitation’ process in Nepal, such as ‘verified’, ‘disqualified’ and ‘minors’. It is these kind of entanglements – between subaltern expressions of political agency and discourses and practices the remit of which is international – that my work continues to be occupied with.

What to do when confronted by: ‘I am tired of politics’

When starting the fieldwork, I had assumed that I would be researching forms of collective struggle – informal or formal ways of organising that had emerged in the post-conflict context as avenues to express grievances in relation to the party, the UN actors or the government. Yet, I hit a wall when trying to find out about ways in which the women I met were ‘involved’ in activities that were associated with the party or activities that involved other ex-PLA combatants. Expressions such as ‘I have contributed enough’ ‘I am tired of all that’ emerged in some form in all the first interviews I conducted.

At first I found myself wondering whether I was talking to the ‘right people’, where were the women who were more ‘involved’? Relinquishing the desire to find what I was looking for, I started to explore what was at stake in these comments – in the dynamic I have come to call ‘withdrawing from politics’.

When I met with Anar who had been a platoon commander during the war for the second time I asked her to tell me a bit more about what she meant by being ‘tired of politics’. She responded with a long, detailed story about her involvement/non-involvement in politics of which this is a short excerpt:

‘My husband thinks that we need to be involved in politics. After all we have spent so much time and effort in yesterday’s war, and how can we just leave it like that and stay home. Life itself is politics. So he feels that it is important to be involved. But I disagree and always tell him to leave politics. We have not gotten anything out of it. I don’t think we have a future in politics … But me, personally I am tired of politics, although my husband is not yet. He has this strong will of getting into politics and has a dream of doing something in the political sector. For me, in comparison to politics I chose business and entrepreneurship and taking care of my family. That is my opinion.’ (Interview, Anar, Nawalparasi, 10th December, 2013)

In the policy discourses of ‘gender and peacebuilding’ in Nepal (and beyond) there is an answer at the ready regarding what is at stake when women ex-combatants move away from active involvement in politics: re-strengthening of regulatory gender norms and women’s concomitant ‘return’ to domestic duties and the private sphere. This narrative of ‘return’ that official discourses of gender and peacebuilding in Nepal (re)produce constitutes women ex-PLA combatants primarily as ‘conflict affected women’: as ‘affected by’ what seems to be an inevitable ‘backlash’, that is, stigmatisation and strengthening of societal gender norms. Within the narrative of return female ex-combatants are positioned as ‘affected by’ the policies of the Maoist party and more broadly by the ‘politicisation’ of the process of army integration and rehabilitation.

Yet the narrative of return fits uneasily with the stories that the women I met, including Anar, shared with me. And importantly, it is a reading that they were painfully aware of and explicitly resisted. Sarika who had been a low-level commander called out this reading, growing frustrated about my ill-conceived questions in our first interview. When Sarika explained that she no longer contributed to party activities I asked whether ‘women’ faced any difficulties in being involved in politics, specifically, if having had children made it more difficult to continue being involved, she responded:

‘Nothing can stop us. When there was war we used to carry two children along with rifle and bag, one child in front and one child on the back. We can work in any situation; we have examples of going on fighting when we were pregnant and giving birth to children. Now, children have grown up, we can be better fighters now.’ (Interview, Sarika, Nawalparasi, 23rd May, 2013)

I argue that if confronted by: ‘I have done enough for politics’, ‘I am tired of politics’, feminist analysis of post-conflict responds by holding on to the narrative of ‘return’ not very much new enters the picture. Rather, we risk perpetuating precisely the kind of gendering that the women I met vehemently rejected, that is: as women they had exercised agency during war through their participation and this form of agency is constrained in the post-conflict context to various extents – and it is the constrains that need to be foregrounded in the analysis.

What if instead of constrains to a preconceived form of ‘women’s agency’ we foreground the following question: what has happened to ‘politics’ in the post-conflict context? Has the meaning of politics shifted – from a ‘struggle’ to ‘career’ or a ‘sector’ as Anar described? Or the location of politics geographically from the rural to the urban/the capital? Who in the post-conflict context has access to what kinds of politics?

Relatedly, what if we take a step back and ask what is at stake when women ex-PLA combatants ‘withdraw’ from politics. Could the withdrawal be a negotiation in relation to the party? A way of withdrawing contribution till the time is right or till the contribution is indeed recognised? In short, I argue that withdrawing from politics needs to be explored as a possible site of political agency. To get to such a line of questioning it is necessary for feminist analysis to leave the perhaps more comfortable ground where ‘women’s political agency’ is from the outset tied with a specific goal: resisting and transforming regulatory gender norms.

These are the kinds of questions I sought to pursue in my project and no doubt continue to be occupied with for years to come. The rich fieldwork underpins mine, and Amanda’s, curiosities with the ways in which politics gets redrawn in transitions, blurred boundaries of military to market and conflict to post-conflict.

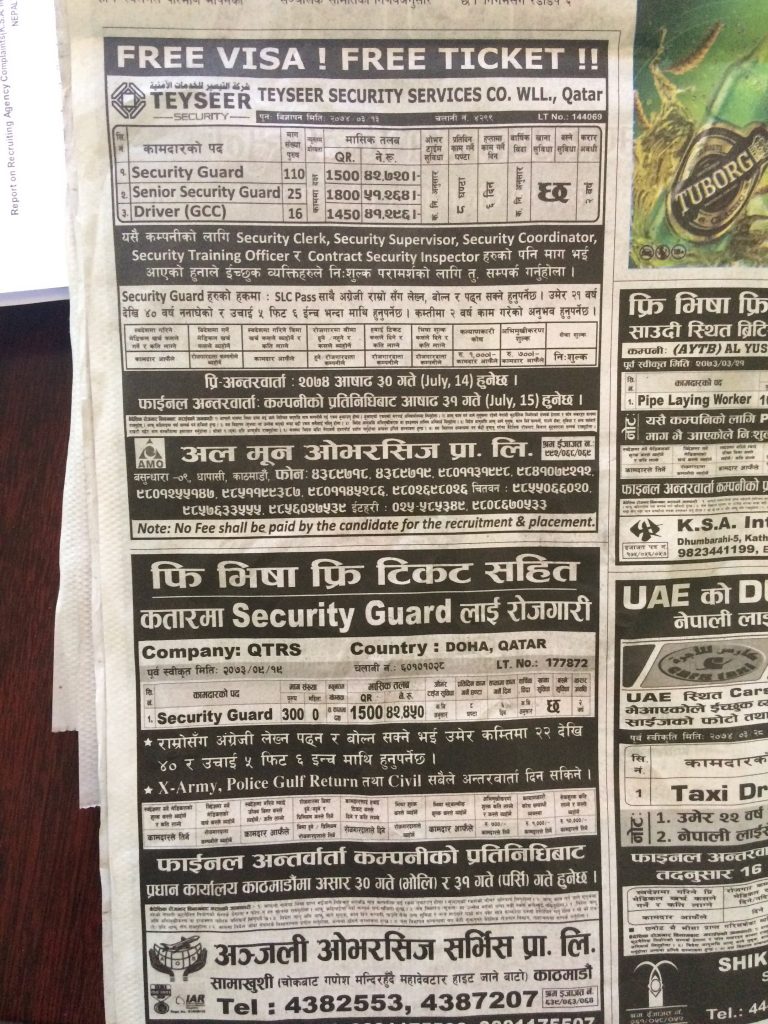

I cannot wait to get started in analysing the fascinating material Amanda has generated through her ethnographic research and to embark on a new research agenda that so closely echoes my previous research interests and allows me to continue to explore the politics of post-conflict Nepal. I’m curious for example, at the ways in which military identities and relations to the state differ between the martial raced Gurkha and the ex-Maoist female combatant. In what ways do intersections of race, gender, sexuality, age and caste embody political and economic subjects—from Gurkhas, to unarmed foreign security contractors, to female ex-fighters.

Hanna Ketola has recently completed her PhD from Kings College London. She is currently the research associate for “From Military to Market”.

Hanna Ketola has recently completed her PhD from Kings College London. She is currently the research associate for “From Military to Market”.

Private Military and Security Companies (PMSCs) are part of a multibillion-dollar industry supplying both security and logistical services for governments, commercial groups and Non Government Organisations (NGOs). The roles these companies perform include, but are not limited to, security consultancy and armed contracting, recovery of hostages, and logistic support services such as construction and infrastructure support including waste disposal and goods transportation.

Private Military and Security Companies (PMSCs) are part of a multibillion-dollar industry supplying both security and logistical services for governments, commercial groups and Non Government Organisations (NGOs). The roles these companies perform include, but are not limited to, security consultancy and armed contracting, recovery of hostages, and logistic support services such as construction and infrastructure support including waste disposal and goods transportation.