The application processes for Doctoral Training Partnership PhDs promoted a current PhD student, Hania Fiaz, to ask me if we should question how well the those processes are encouraging and supporting a broad range of applicants. We ended up presenting our findings at two conferences here are the findings.

In short the narratives presented to us suggests a quite different experience for students who make it onto a research degree from a less privileged background. Differences in the topics funded and the nature of the application process will influence prospective students as to whether they apply, and what they might expect once they begin their degrees. The statistics show a relative underrepresentation of women and ethnically minoritized groups. We speculate there is significant influence of background and wealth, which determines which University students complete their undergraduate and masters degrees. Students with guidance and effective role models are more likely to go on to PhD. The relative drop in the proportion of women undertaking research degrees probably relates to relatively large amounts of funding for Engineering and Computing, which are male dominated.

Abstract for Advance HE conference – Equality, Diversity and Inclusion Conference 2025: The sum of many parts: Embedding intersectionality in HE practice

Summary abstract: There has been a trend toward the redaction of information from applications to support a fairer approach, and to encourage entry to doctoral study from a broader range of applicants. The data considered suggests that some demographic groupings may continue to be marginalised by this process. This research considers the intersectional influence of socio-economic status and ethnically marginalised groups. We argue that to most effectively promote and support engagement into doctoral study that all information should be considered and contextualised. Addressing unconscious or conscious bias requires the assessors of applications to consider trajectory and growth not only current suitability.

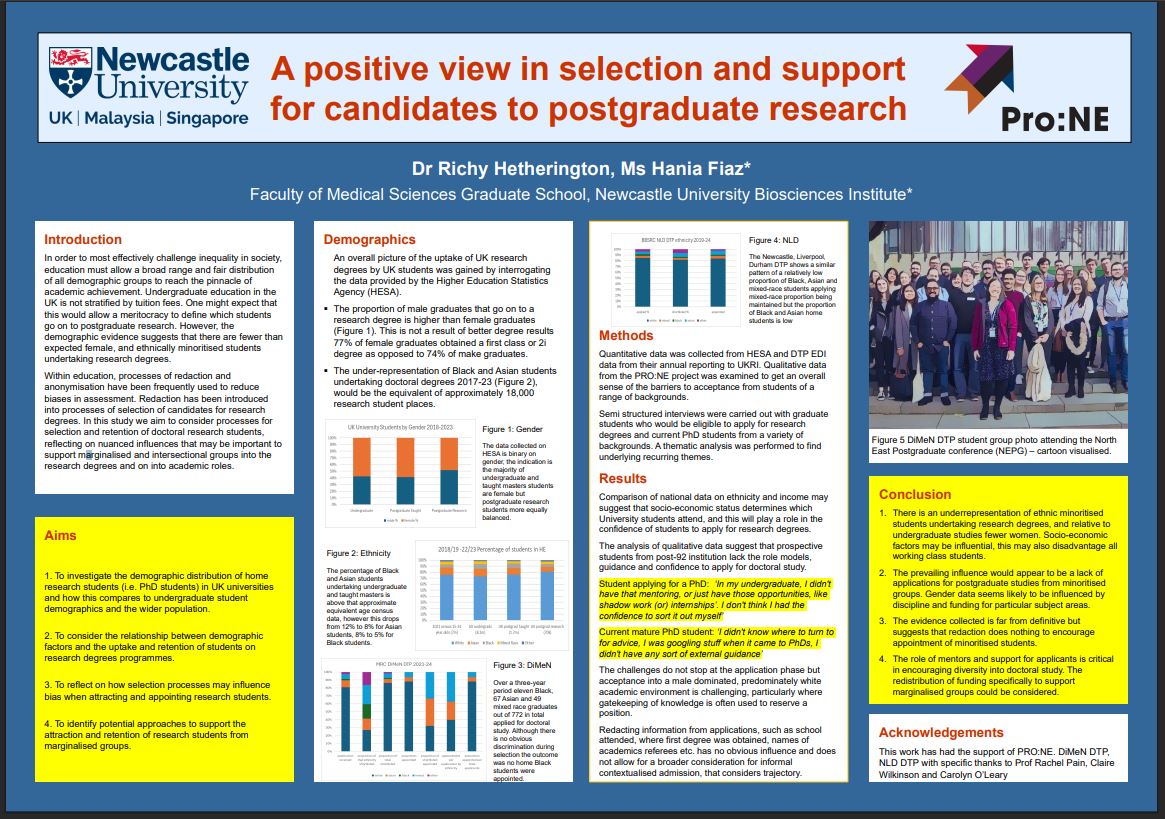

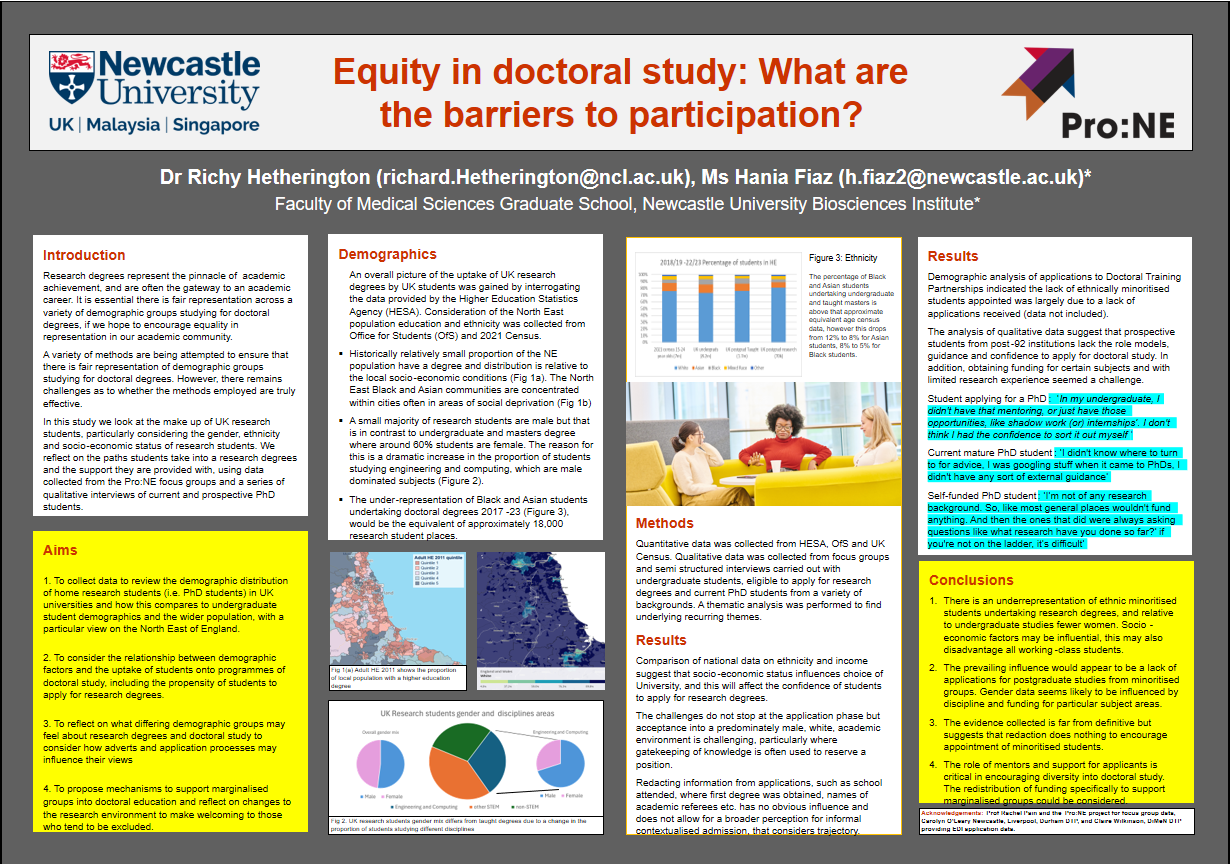

This is the poster for the Newcastle University Learning and Teaching Conference.

Summary for the Learning and Teaching Conference

A variety of mechanism are being employed in an attempt to promote Equality, Diversity and Inclusion in doctoral research students. In this study we have attempted to investigate the processes and whether meaningful developments are being made in research student inclusivity. Demographic data suggests certain groups are underrepresented in doctoral education in comparison with those studying at degree and masters level, we hope to identify possible causes for this reduction in inclusivity.

Abstract for the Learning and Teaching Conference:

In many areas of society inequality and implicit biases are known to cause discontent. In order to most effectively challenge inequality in society education most allow a broad and fair distribution of all demographic groups to reach the pinnacle of academic achievement, only by having a broad community influencing future selection can the appropriate role models be in place and can equity in selection be reached. Within education, processes of redaction and anonymisation have been frequently used to reduce biases in assessment. Redaction has been introduced into processes of selection at the highest level of education (H8). In this study we aim to consider processes for selection and retention of doctoral research students, reflecting on nuanced influences that may be important for the support of marginalised and intersectional groups into the highest level of academic achievement and on into academic roles.

Script of the short presentation to accompany the Advance HE Posters

“In the UK, educational outcomes for school students can be affected by the student’s background and socio-economic status. One might hope that by the time students reach doctoral level education, the potential positive influence of social mobility through graduate and master’s education will all for a truer meritocracy and the advantages of privilege will be diminish. However, the data provided by HESA on home students’ participation in doctoral degrees show some disappointing demographic trends.

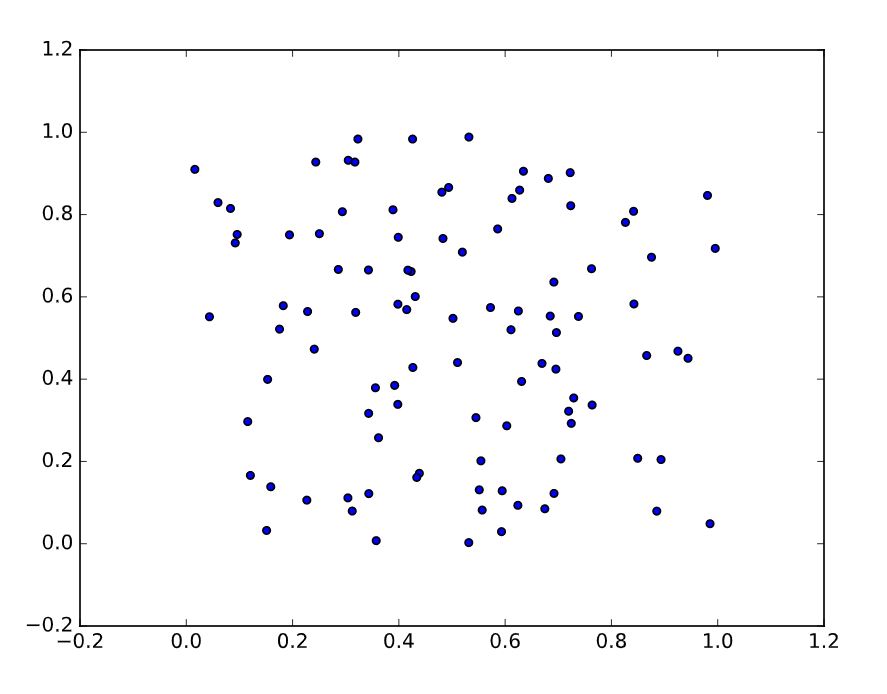

Undergraduate degrees in the UK are more popular with women than men and around 60% of degree places are held by women, although whilst women are marginally more successful in achieving first class or upper second class degrees this advantage does not translate into doctoral education where just under 50% of students are female.

Black and Asian students at undergraduate level match the national average of the population in terms of participation at this level but there is a stark drop when it comes to enrollment into doctoral degrees. Around 12% Asian and 8% Black students at undergraduate level drops to around 9 and 5% respectively when it comes to undertaking a research degree. These small percentage changes may not seem significant but over the four year period in which these data were collected that equates to around 18,000 Black and Asian students not taking up the research degrees that might be expected in a more equitable system.

There has been some recognition of these issues of inequality or lack of diversity in doctoral education. Measurements have been made and processes have been altered to try to address these issues. The introduction of the UKRI’s Doctoral Training Partnerships (DTPs), Doctoral Training Centres (DTC) and now Doctoral Landscape Awards (DTAs) had provided a mechanism to determine uptake of students from minority or disadvantaged backgrounds.

It was not possible to obtain data from UKRI for all of these different partnerships and centres. However, a brief analysis of the records taken for two partnerships gives a clear indication of a significant challenge. That is the number of applications made from certain groups. Once applications are in there appeared to be no obvious sign of discrimination but the lack of applications leads to few appointments being made for those from a diverse background.

We interviewed a variety of students from a range of backgrounds, who are studying for a doctoral degree or are who are in the position to apply, in order to get a sense of the challenges or barriers to participation. The results of the interviews painted and intriguing picture, where lack of support and encouragement for certain students felt completely at odds with the guidance other students were given, regarding the pursuit of higher education and the subsequent application process. Forms of imposter syndrome, a lack of role models, and challenges of background proved powerful restrictive barrier to engagement. A ‘stay in your lane’ mentality prevailed.

The use of approaches such as redaction in the application processes appears to have limited to no positive influence in changing the innate biases within the system. Excluding information on educational background may aim to avoid overt bias but there are many proxies built into questions such as ‘describe your research experience’. If applications processes are not able to consider the broader, transferrable skills gained from a variety of experiences on entry then there will be very little opportunity for students from a disadvantaged backgrounds to continue with a positive trajectory.

Work from the Pro:NE project aligns with our findings but also points to some significant differences in processes due to discipline and associated differences with how appointments are made depending on funding. Overall, the combined findings suggest that there is a much greater need for undergraduate and master’s students to have the support and mentorship that will encourage them to apply. There is also a need for contextual admissions processes that encourage applicants to consider making applications because of their broader experience but equally for the assessors of applications to consider the trajectory of potential research students. Looking for the broader skills that can be appropriated into doctoral study. The search for individuals that can bring new ideas and ways of thinking into research may eventually lead to having a more diverse academic community and allow prospective students to see how they could fit it in. If you cannot see it you will not be it. A generational shift in broader acceptance needs to be made so in future generations there is a greater recognition of the value of diversity.“