A study conducted in the mid 2010’s at Ghent University in Belgium provided some hard evidence (1) for what a fair few of us had suspected for many years. That the wellbeing and mental health of PhD students, and most probably all Early Career Researchers, is in a quite perilous state.

Researchers love to research so a series of subsequent surveys, questionnaires, interviews and reports were funded and actioned (2). The results suggested what we might have expected that the PhD students at Ghent were by no means an outlier but were quite typical. With larger surveys and reviews indicating around one in four research students disclosing issues with their mental health (3). A number that is far greater than other groups of a comparable age. What is probably most worrying within those statistics is the pressure not to disclose any issues due to the potential detrimental influence on a researcher’s career prospects is likely to mean many more researchers are keeping their problems to themselves.

Whilst correlates of mental health difficulties have been identified (4) the overall issue would appear to be a systemic and existential problem in what the doctorate and a subsequent research career looks like. When universities attempt to attract research students to enrol, there is little to no mention of the potential negatives that lie ahead.

Once doctoral students start their programmes the mixed messages will become apparent. The inductions from Graduate Schools, Doctoral Colleges or whatever larger structures will explain that their education is about their own professional development and to take time to engage in the many opportunities available. However, the day to day messaging they will receive from their supervisors, research associates, and senior PhD students may be quite different. The all consuming requirement for, data generated, high impact factor papers published and grants in, becomes a frenzied narrative of career dependence.

The sense of competition and requirement to spend more time researching to compete in the race to fulfil the REF (Research Excellence Framework (5)) requirements of the unit and institution quickly trickles down to a doctoral student just hoping to get to grips with their own project. Fundamentally if we really want to see a significant improvement in how researchers feel then there will need to be a radical shift in the way research is set up. (see another blog post https://blogs.ncl.ac.uk/richardhetherington/2021/02/07/2020-a-vision-for-portfolio-careers-in-academic-research/)

Whist we wait for the great leap forwards, the question remains what can we do about the individuals currently caught in the crossfire of expectations for research outputs and personal and professional development? The first thing is to draw no division between the support and guidance that is technical, and is primarily there to provide tools to help with research and, the support that is for the individual to cope well with the research experience. So, when wellbeing services do recognise that the needs of PhD students are very different to undergraduates (PhD students are much less likely to be homesick for instance). Then the support which is provided is clearly signposted without any potential for stigmatisation by making it clear that personal development and support dealing with challenging situations is normalised as is counselling.

Research students should be able to access Cognitive Behavioural Therapies (CBT), talking therapy based workshops, or mindfulness meditation sessions in the same way as they would guidance on academic writing or statistics. Far better we are able to help researchers before a crisis point than wait until they hit to rocks or are standing on the levy.

For those who are heading toward a crisis point because of complexity of their research or the many other factors that may play a part in making life difficult, there needs to be appropriate support and well directed guidance. This is where the support and guidance provided to supervisors is key. This most complex of working relationships needs the recognition of boundaries and knowledge of signposting to adequate and timely resources. Supervisors are often friends and mentors to their students but they are not mental health counsellors and if a student’s problems go beyond their research project they should be given appropriate support from trained professionals.

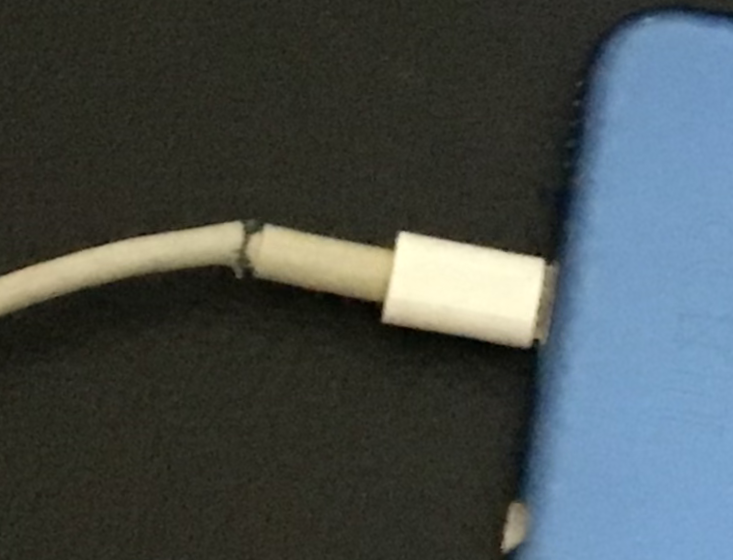

So what can institutions introduce that might help researchers keep a sense of perspective and avoid the worst of the situations that might cause problems for their mental health. Here is where I link to my somewhat cryptic image, the reason my phone charger (like many, I guess) has broken at this point is because I’m trying to use the device whist it’s on charge, or I’m quickly pulling at it to draw it back into use when it has been charging. Dedicated researchers are generally so engrossed in their work that they are naturally drawn away from their time recharging. When they are not at the desk, bench or PC they are still thinking about the work. There needs to be freedom to escape and recharge. The first thing is not to amplify further their engagement with the research by making external demands of them to do more. Their own pace for a PhD is almost always fast enough (6).

The other thing is to structure the opportunity for support. Mindfulness meditation might not be for everyone but for those it works for, it really does make a massive difference. It helps people to live in their current moment and frees them up for the worries of what has not gone to plan or challenges that might lie in the future. Having Mindfulness sessions available is a real tangible way to help researchers manage the challenges they face. For others, who are happiest when they get something done, they may need something that is achievable to satisfy the need for some instant gratification that can often be lacking in the very long term goals and outputs of research. For those students community activities such as organising events like the North East Postgraduate Conference NEPG (7) could be one option. For other more individual pursuits like gardening or origami (8) may prove to be a source of some satisfaction. The recognition that time for these recharging processes is key and supervisors should encourage students to build these activities into their day. Productivity comes from happiness and being at ease with requirements not the constant pressure of needing to generate more data or outputs.

Finally, whatever the Universities choose to put in place to support their research students, there must be adequate resource for such support to continue through development. Research on any intervention ought to be through practitioner based enquiry with iterative development of good practice. This should not be an opportunity for researchers to further their careers as they observe from afar, assessing the potential influence of one off projects or schemes. There is surely enough compelling evidence that comprehensive support is needed for researchers to manage the challenges of research and the academic world. The question is should not be what is the one answer but how does the sector keep helping those who will need help.

1.https://biblio.ugent.be/publication/8613173/file/8613174.pdf

2.https://www.officeforstudents.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/student-wellbeing-and-protection/student-mental-health/catalyst-fund-supporting-mental-health-and-wellbeing-for-pgr-students/

3.https://systematicreviewsjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13643-020-01443-1

4.http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/id/eprint/102260/1/UDOC%20Survey%20Predictors%20of%20PGR%20symptoms%20BJPsychOpen%20Accepted%2011.10.21.pdf

5. https://www.ref.ac.uk/

6. Berg, M., & Seeber, B. K. (2016). The slow professor: Challenging the culture of speed in the academy. University of Toronto Press.

7. https://ne-pg.co.uk/

8. https://www.vitae.ac.uk/events/past-events/vitae-researcher-development-international-conference-2017/Posters2017/Can%20mindfulness%20through%20meditation%20or%20Origami%20be%20used%20to%20support%20resilience%20and%20well%20being%20in%20researchers