Playground games (from playgroundfunforkids.com)

My son started primary school this year. Watching him walking into the classroom on his own for the first time was terrifying because I really didn’t know how he was going to manage somewhere which requires so much conformity and where there are so many rules. As it turns out it was playtime, the only bit of unscheduled time in the whole school day, that he had most difficulty with in those first few weeks. And this was precisely because it’s the time of the day when there seem to be fewest ‘rules’ in place. This is the part of the day when children are not required to do their lessons, be quiet, or sit down with their arms crossed and their fingers on their lips. Instead they’re left to manage themselves and their friendships on their own. It’s the part of the day where all the pushing and the teasing and the raspberry-blowing and the chasing and the wee-your-pants social anxiety happens. I’m sure that if we reach back into our own memories we can all remember at least one terrifying moment in a huge, dangerous playground without a best friend beside us. It’s the kind of memory that your body holds on to in spite of you and so even if you can’t recall the details I’m willing to bet you can still feel it in your stomach. It’s a deep-seated fear because what we’re really scared of is ourselves: we don’t trust ourselves to be able to communicate with other people and to make ourselves understood without losing something — an eye, a friend, our dignity — in the process. I heard another parent describe playtime at my son’s school as being ‘like the Wild West’, because of its lawlessness: who will protect our children from the rustlers, outlaws, and gunslingers that they become when left to their own devices? The playground is scary, because play is scary. And who wants to play a game when they don’t know the rules? But one of the best things my son’s school does to help new children settle in is to set them up with ‘play buddies’ (usually children from some of the older years) who will teach them the rules of playground games — things like ‘grandmother’s footsteps’, ‘what’s the time Mr Wolf?’ and the unpromisingly-named ‘toilet tag’. My son loves playing these structured games, and I am so relieved that they all have rules to help the children to play without injuring one another. Rules, it seems, can help lots of situations seem less scary for everybody involved. Rules are not only for telling us what not to do, they can also help us to work out what we should be doing, where, when, how and with whom. Rules can help us to learn how to relax, have fun, enjoy ourselves. And, once we understand how they work, rules can be stretched, manipulated and embellished in all sorts of exciting ways.

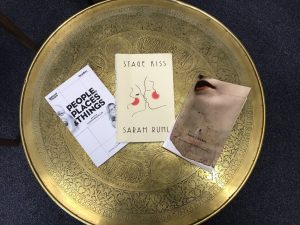

Starting school for the first time is for many people the first really big change they experience in their lives, and in certain respects it’s not so very different to starting as a first year undergraduate. I can remember how I felt when I registered at university, when I sat in my first lecture and when I joined my first seminar group — it gives me the same sort of visceral feeling as those stomach-churning playground memories. And I think I can imagine how it must feel to be a parent whose child is leaving home to go off and study. But I’ve been teaching in universities for over a decade now and so it can sometimes be difficult to remember that what seems so obvious and natural to me — the shape and structure of lectures, seminars, workshops — might be unfamiliar to all of you. Seminars and workshops, in particular, rely upon student participation and it can be frustrating for staff when a class don’t seem to want to take part. But it’s difficult to get involved, isn’t it, when you don’t know the rules of the game? Part of what we’re hoping to do in this module, is to help you to think about what is required of you as a participant on a humanities degree, and how you can make the most of all the resources that are available to you. Yes, you can learn a lot from attending lectures and making good use of the library, but perhaps the most important resource available to you is one another — there’s so much that you can learn by asking questions of your peers, talking to one another about what’ve been reading, and finding ways to test out your ideas as a group. So I hope you’ll think of all the staff teaching on this module as ‘play buddies’ like those in my son’s school — we’re here to show you how you can participate and to help you work out what the rules are, all the rest of it is up to you.