By Catherine Landers

“No Wounds but Cupid’s discompose our Mind,

And if we are cruel, ’tis when we are kind.”

(Prologue, lines 9-10)

What would you decide, if life was forcing you to choose between duty to your country and true love?

The Unhappy Penitent (1701) by Catharine Trotter, with its themes of love, loyalty, deception, duty, war and friendship, transports you to life in the French Court, led by Charles VIII (reign: 1483-1498).

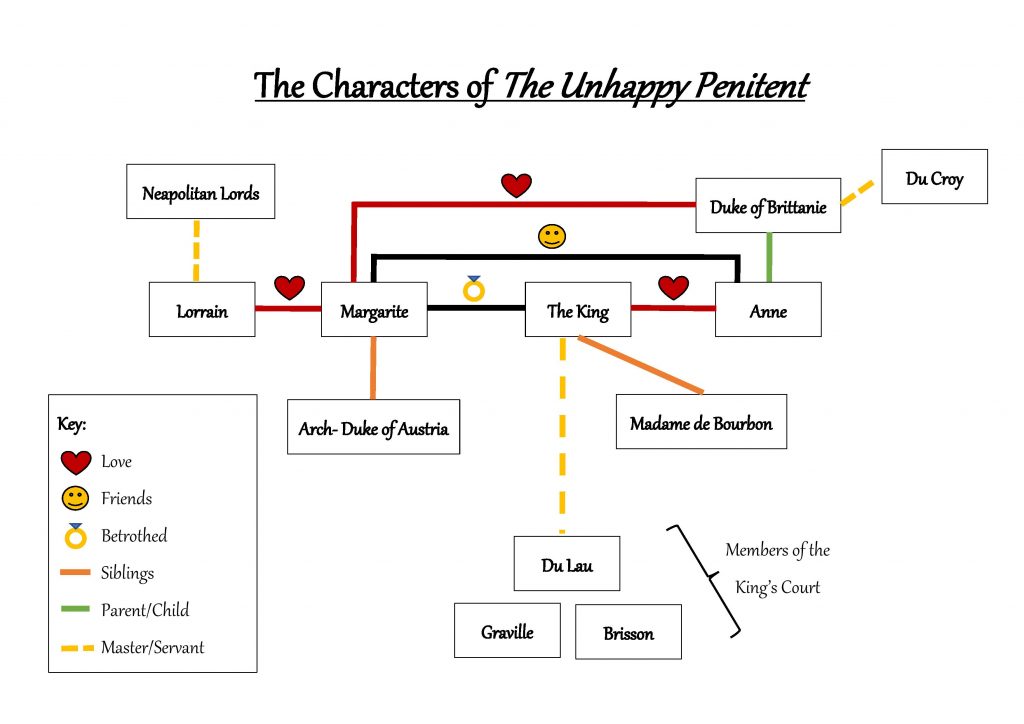

Who’s who

What happens

- Act 1

- The King is torn between marrying Anne for love, or his betrothed, Margarite, in order to ally his country with Austria. His sympathetic court supports an alliance with Anne.

- Margarite is desperate to escape the King’s contract, and marry her lover, Lorrain, instead. Act 2

- Lorrain is under pressure to claim leadership of Naples from the tyrant Ferrand, and is struggling between that duty and his desire to stay in France to secure Margarite.

- Anne advises Margarite to write a letter to the King asking to be released from the betrothal. Act 3

- The King returns his favours to Margarite after finding out about her affair with Lorrain. He suggests they listen to some music in order to inspire her to love him again.

- Against Anne’s advice, Margarite secretly marries Lorrain in order to legally escape her obligations to the King. Act 4

- Meanwhile, the Duke of Brittanie, Anne’s father, also in love with Margarite, plots to undo her relationship with Lorrain by planting a forged letter from the King, insinuating that Margarite has lost her virtue to the King.

- Reading this letter after his marriage, Lorrain is humiliated and refuses to hear Margarite defend herself.

- Brittanie secures Margarite from further defending herself by claiming the King would kill Lorrain should she try.

- Powerless to negate the accusations, Margarite withstands losing the respect of her brother, and Anne. However, once convinced of her innocence, Anne allies with Margarite against the King. Margarite vows that if her name is cleared, she will forfeit her life to Heaven and become a nun. Act 5

- When persuading Lorrain to leave for Naples, Brittanie learns about his marriage to Margarite. Mortified at his own actions, he escapes the country, leaving behind a letter that describes all his actions.

- Meanwhile, the King protests his innocence, much to the frustration of the princesses, and challenges Lorrain to a duel.

- Austria reveals Brittanie’s letter. The King and Anne unite. However, against either of their wishes, Margarite chooses to further prove her honour by respecting the vow she made instead of uniting with Lorrain.

- Lorrain threatens to kill himself and/or Margarite rather than let her become a nun.

- Anne, Austria and the King conclude the play with a warning against following passion instead of virtue, else our happiness be too short-lived, or our desires be revealed as false.

The Play in its 1701 Context

Catharine Trotter wrote The Unhappy Penitent two years after the publication of a rather influential essay by Jeremy Collier entitled A Short View of the Immortality and Profaneness of the English Stage. Among his many critiques of the way 17th century theatre was conducted, Collier highlights the way immoral behaviour of characters portrayed on the stage is rewarded, rather than frowned upon. In her dedication to the play, Trotter aligns herself with Collier when she pays homage to the moral obligations of the theatre, and more immediately the playwright, when she says “…’tis sure a Divine [policy] to contrive that [the People’s] very Pleasures be made their Instruction…”. For Trotter, her plays were not just about entertainment, but moral instruction. This speaks into the wider cultural changes, epitomised in the theatre, as the licentiousness of Charles II’s court, is reined in with the more reserved court of William and Mary (reign: 1689-1702). For more information on how Trotter uses the genre of tragedy to present her moral, click here.

The way that Trotter portrays her female characters as rational and moral went against the grain of femininity at the time. Women were supposed to be unthinking, passionate beings, yet Trotter’s “female characters become increasingly proactive…displaying moral responsibility and supportiveness to both men and other women” (Kelley, 97). In The Unhappy Penitent this role is fulfilled by Anne, who repeatedly re-centres the King and Margarite into acting with virtue. This led to Trotter receiving a backlash of criticism, and even taints on her reputation as a virtuous woman as other female playwrights insinuated that Trotter did not practice what she preached (Kelley, 17). Later in her life, Trotter was able to restore her reputation when, as a married woman, she published her philosophical works.

Why is it still relevant now?

Never has a play been more relevant in England than when her prince marries for love and later chooses to renounce his public responsibilities. Prince Harry was confronted with the same decision as the characters in this play – what is more important: love or duty? Anne’s wise words, “We owe our care first to be justify’d | To our own Thoughts, next to the World’s” (Trotter, 13) parallel the choice made by Harry, as he firmly put family before his title. Likewise, the play negotiates the relationship between personal choices and the effects they have on our wider connections.

Contrary to expectation perhaps, this play is not about passive women who wait around for their men. Anne’s advice to Margarite, “Be Mistress of your self, and firm to Virtue” (Trotter, 14) shows a brave break from the patriarchal authority women in 1701 would be under, and a clear similarity to the modern-day maxim of “Be true to yourself”. Margarite uses this agency when Lorrain offers her the chance to marry him secretly, and she “refuse[s] to be my self the Victim” (Trotter, 21) and as such she stands as an encouragement to us all to recognise our own agency. She chooses to be true to herself and her word, and at the end of the play, as the Prologue spoils, “The desperate Nymph renounces all Mankind” (Prologue, 18). Far from being dependent on the affection of her lover, she decides to become independent from what she perceived to be a harmful relationship. This blog delves deeper into the feminist message of this play here.

The language used in the play’s conclusion of placing virtue over passion may seem outdated, however, when contrasted to the saying of “be careful what you wish for”, the events of the play are brought into the ironic light it could be argued Trotter was aiming for. Blinded by their love for each other, the characters forget to evaluate their desires to find out whether they are indeed what they truly want to pursue. As Trotter asserts in the dedication of the play, “if we resign…the heart [to Love], let us not give him up the Judgement too” (Dedication, 3). In other words, don’t be stupid in love. It is that message which further brings this play into the modern day.

Bibliography

Kelley, Anne. Catharine Trotter: An early modern writer in the vanguard of feminism. Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2002.

*To make the quotes from The Unhappy Penitent easier to read, I have replaced the long-S with modern-day ‘s’. This is the only change I have made to this text; all spellings, italics and line breaks are as in the manuscript.