By Catherine Landers

Trotter’s use of tragedy in implementing her moral.

Catharine Trotter would have grabbed audiences’ attention when Mrs Oldfield introduced The Unhappy Penitent as a “bloodless tragedy” (Prologue.13). As a writer, Trotter was adamant that her work would simultaneously entertain and instruct her audiences (Dedication, 4). Her rejection of the much-anticipated spectacle implies that she recognised more in the power of tragedy; this becomes clear when considering the play’s moral. The Unhappy Penitent presents a warning not to surrender “Reason for Passion” (Trotter, 5.481-491). Trotter uses the medium of tragedy, not just to present this philosophical message, but to force her audience to put it into practice. Analysing the scene between Anne and Margarite in Act 3 reveals how Trotter does this. Linking the play to contemporary philosophy then helps us to understand why it was important for Trotter to instruct her audiences in this way.

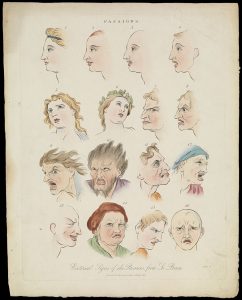

In the eighteenth century, the word “passion” related to “a strong or overpowering feeling or emotion” (OED, 6b). In Act 3, Margarite’s reaction to the King’s returned favour becomes highly passionate. She explicitly describes the emotions she suffers; she is “miserable” (3.196), “wretched” (3.211) and betrayed by Anne, her now “Cruel Friend” (3.209). Tragedy was a genre associated with portraying such passions onstage (Hoxby, 91), but what is key here is the encouraged audience response.

Trotter states that “to move Compassion…is one of the chief Ends of Tragedy” (Dedication, 1). The “sight and sound” of Margarite’s display of grief and anger would have encouraged “answering emotions” in the now “agitated…souls of the audience” (Hoxby, 66). These emotions would have been either pity or fear (Hoxby, 62). In 1640, Thomas Hobbes defines pity as:

…imagination…of future calamity to ourselves, proceeding from the sense of another man’s present calamity; but when it lighteth on such as we think have not deserved the same, the compassion is the greater, because then there appeareth the more probability that the same may happen to us.

(Hobbes, 30-31)

The self-interestedness of Hobbesian theory is clear – we only feel compassion for someone’s situation because we wouldn’t want the same thing to happen to us. Significantly, this same selfishness was vital to an audience’s enjoyment of tragedy. Eighteenth-century writers like David Hume, John Aiken, and Anna Laetitia Barbauld’s observations on this topic are summarised by Hoxby in the maxim: “Tragedies please…because our inner knowledge that we are watching a fiction affords a sense of security that permits us to feel agitated without feeling truly threatened” (104). Margarite’s situation appears undeserved, and her “agitation” inspires the audience to feel pity whilst feeling safe in its fiction. Part of the pleasure of going to watch a tragedy stems from the cathartic release of this pent up emotion. Correspondingly, Margarite describes how these feelings are inviting her to respond: “To rail, to rave, to grieve…” (3.211), “vent my extravagances” (3.238) then “feel for each anticipated Torture” (3,240). This highlights Margarite’s, and arguably the audience’s, desire to dwell on these emotions to fully experience them.

If tragedy has this power over the passions, the playwright controls to what extent. For Hobbes, passion “is in part a matter of cognition: it involves beliefs about what sort of power we possess and what we can do with it” (Tuck, 184). Similarly, writing in 1694, Locke (of whom Trotter was a big fan) recognises free-will, defining it as “the power of considering ideas and of suspending and deciding on action” (Schneewind, 203). Thus, Reason is the source of power from which originates our self-control. Mirroring these theories, Trotter places Reason in the midst of Passion. Anne gives voice to that Reason. She is constantly encouraging Margarite to evaluate her feelings and consequent behaviour. Most significant is the moment when Anne asks Margarite to “Consider –” (3.236), the dash illustrating Margarite’s immediate interruption with “I will consider; | But let me first vent my extravagance” (3.237-8). Margarite explicitly rejects Reason in preference to indulgent Passions. Although Margarite can choose to reject Reason, arguably Trotter does not allow her audience the same luxury. Instead, by raising awareness of individual emotional control, Trotter encourages her audience to put the moral of the play into practice.

Writing in 1611, Daniel Heinsius describes the theatre as “a kind of training hall of the passions” (Hoxby, 65). Trotter is using it in a similar way, not just to train the audience into feeling those passions, but also how to respond to them. Anne’s moral intrusions stop the audience from fully entering into the high emotions portrayed by Margarite. For example, Margarite accuses Anne with “Oh Madam, what have you done! How miserable | Have you made me!” (3.196-7). The exclamation marks and the “O” illustrate the emotional force this should be delivered with. This inspires the audience’s pity for Margarite. Anne answers, “Could you have justify’d | Your Marriage…knowing | Your Contract with the King is still in force?” (3.198-200). Here Anne is asking Margarite to stop and evaluate her behaviour, encouraging her to remain virtuous and moral in the act of loving Lorrain. Later she asks the same about Margarite’s speech: “scorn the baseness of the thought you mention” (3.207). This offers a pause for the audience to consider their own responses to Margarite and evaluate their own emotions. Being outside of the situation, it is easier for them to apply reason to it, and therefore their passions remain under control. They do not experience the cathartic release of emotion because they do not need to. The subsequent events of the play, align passion with foolishness. This transfers the audience’s sympathy to Anne who remains dignified. She does so by implementing reason. Therefore, ironically, some of the satisfaction earned through this play is not due to a cathartic release of emotion, but the morally superior knowledge that you can control it.

If an audience can desist from losing themselves to their passions in the theatre, they can do the same in real life. Not only that, Trotter incites in the audience a Lockeian sense of obligation to do so (Schneewind, 206) – their possible punishment being “dark and muddy ways…[that] exposes us to shame” (Trotter, 5.488-90). Hence, the play, performed in a theatre, supports Locke’s philosophy that everyone can share the same knowledge of what is right and wrong, without there being room for individual relativity. The Libertine culture was “opposed to reason and control” (Kelley, 107) and fundamentally legitimised by Hobbesian moral relativity. Trotter exposes the immorality of Libertine behaviour by portraying the danger of surrendering reason for passion and, critically, placing the audience in a position of complicit agreement.

Bibliography

Kelley, Anne. Catharine Trotter: An early modern writer in the vanguard of feminism. Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2002.

Hobbes, Thomas. The Elements of Law: Natural and Politic. 1640, edited by Ferdinand Tönnies, PhD, Cambridge University Press, 1928. https://heinonline-org.libproxy.ncl.ac.uk/HOL/Page?handle=hein.cow/elawnap0001&id=1&collection=beal&index= Accessed, 5th March 2020.

Hoxby, Blair. What was Tragedy? Theory and the Early Modern Canon. Oxford University Press, 2015.

Schneewind, J.B. “Locke’s moral philosophy”, The Cambridge Companion to Locke. Edited by Vere Chappell, Cambridge University Press, 1994.

Tuck, Richard. “Hobbes’ moral philosophy”, The Cambridge Companion to Hobbes. Edited by Tom Sorell, Cambridge University Press, 1996.

- To make the quotes from The Unhappy Penitent easier to read, I have replaced the long-S with modern-day ‘s’. This is the only change I have made to this text; all spellings, italics and line breaks are as in the manuscript.