A Close Reading on Comedic Mechanism’s and how they are employed

Act 1 Scene I of A Wife to be Lett gives insight into the mechanics used within comedies. Within this extract (11), the heated dialogue between the characters of Toywell and Mrs. Graspall illustrates authorial intent as well as gender power dynamics presented through the lens of comedy.

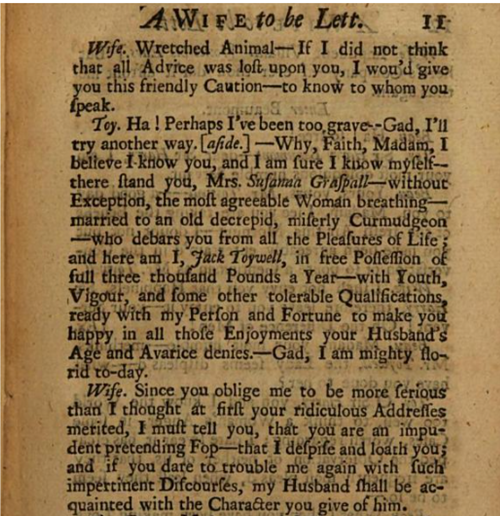

Firstly, one key aspect to this extract is the use of direct address to the audience and the syntactical positioning of stage direction. What stands out in this passage is the placement of ‘(aside)’. This one-word stage direction begs the question of to whom must the actor address and what aspect of their deliverance would be delivered to who. The stage direction comes at the end of what could be addressed to the audience and not to Mrs.Graspall, highlighted by how just after the ‘aside’, Toywell delivers the line ‘Why, faith, Madam’ – directly addressing the other actor on stage, not the audience.

The utterance that is delivered to the audience ‘Gad, I’ll try another way’ is denoted using the punctuation ‘-‘. The use of the dash to embed a line as an indicator for actors when reading the script denotes the implicit stage direction that should prompt a direct address to the audience. This particular instance would be regard as more explicit in being a stage direction as it actively states to the actor to address the line to the audience. Yet later on in this passage, such explicit directions are not given, but the use of the dash to show where the actor must address the audience still continues. It is therefore through the use of such punctation that the comedic element that the character of Toywell performs is readily accessible and conveyed for actors to read.

Yet this relies on the notion that knowledge and who knows what on both the stage and the audience is one of exclusion. Rather, to assume that the actor, in this case Toywell, is only addressing either the audience or Mrs.Graspall at a time. It begs the question, who knows what? If it is in line with the former reasoning, and that Toywell addresses the audience with Mrs.Graspall unaware, only the audience and Toywell know and that is where the comedy lies – creating a comedy of exclusion. But if this notion is deconstructed, and that Mrs.Graspall knows what is being said about her by Toywell, the origin of the comedy lies within an inclusion of knowledge, where Toywell is made out to be a fool to say such things to the very person he wishes to exclude.

Using this mechanism of direct address to the audience also gives an insight into the power dynamics between the men and women on stage. In Mrs. Graspall’s rebuttal to Toywell’s advances upon her, not only does she oppose those advances, but also does not employ the same comedic mechanisms as Toywell had. It must be said that on the physical page, a dash is used in Mrs. Graspall’s lines. Yet it is only used once and is not used to embed a particular utterance. Instead, it may implicitly denote a pause or a potential injunction by the other actor on stage. This notion is evidenced by Mrs.Graspall addresses, shown by the second person pronoun ‘you’ – which is an anaphoric reference not only in the script, but also on the physical stage and the placement of bodies. Therefore, it is only Toywell who is presented to use a comedy of exclusion. To exclude in such a way encourages a sense of superiority as a component of comedy.

According to Thomas Hobbes, “the passion of laughter is nothing else but a sudden glory arising from sudden conception of some eminency in ourselves, by comparison with the infirmities of others”. (54) By this he suggests that comedy derives from the notion of superiority, that in the case of this play, the audience must feel superior to something on stage for the play to be funny.

But who do the audience feel superior to? If Toywell is the only body on stage who employs comedic mechanisms, would the audience laugh with him or at him? Firstly, the case of laughing with him. Lines such as ‘married to an old decrepid, miserly Cumudgeon’ are pejorative in their very nature, thus used as a means to humiliate Mrs.Graspall. It is a means to lower her standing in the power hierarchy of bodies on stage, lending itself to the notion that the comedy lies in the audience feeling superior to Mrs.Graspall. If you couple this with the condition of restoration society that is patriarchal, the comedic element at the time would have very likely been at the expense of the woman on stage, backed up by the evidence already presented. Mrs.Graspall’s lack of agency due to her not employing any comedic mechanism demonstrates a clear power dynamic that favours men on stage.

Despite this, this placement of superiority by the audience could be challenged. Rather than the audience laughing at Mrs.Graspall’s expense, the audience could be laughing directly at Toywell himself. This is suggested by the use of dramatic irony within the passage and the Act itself. It is pre-established that Mrs.Graspall does not like Toywell in the first place as she refers to Toywell as a ‘Wretched Animal’. She believes herself to be superior to Toywell, dehumanising him as well as insulting him in order to maintain her agency. This is a clear indication that Mrs.Graspall will not engage in any of the activities that Toywell pursues. This is pre-established, therefore, it could be suggested that audiences already know Toywell’s advances are a failed pursuit. Thus, with his attempts falling short, the audience may laugh at him as they have knowledge he does not – making them feel superior. So rather than laughing with Toywell, the extract indicates that the audience may laugh at Toywell. It could be further suggested that if this play was performed today, the audience may view the comedic element in this way, presenting Toywell as a clown rather than the one whom has power based upon his gender.