This is rather rough and really just some initial ideas, but I am not sure when I shall get chance to think about it again, so have decided to throw it on and see what happens…

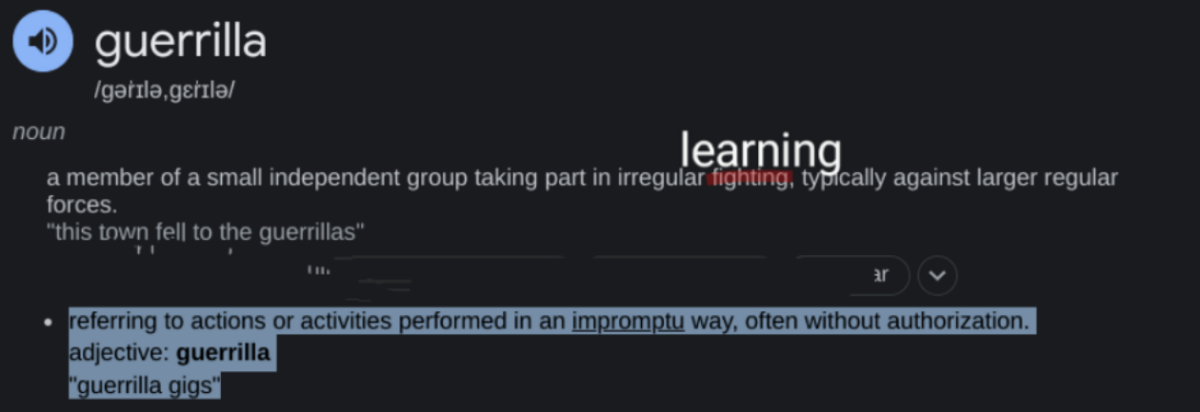

Title of session: Guerrilla Learning: disciplinary thinkers facilitating experimental encounters

Prof David Rose, Philosophy, School X

Title slide (slide 1)

Guerrilla learning is small independent group learning actions or activities performed in an impromptu, irregular way, often without authorization and in the context of larger, regular institutions. This paper will show how guerilla learning can support traditional disciplines, pedagogic innovation, enable an equity of access for learners to encounter other subjects and reflect on the leading edge of discipline research in relation to topics proposed in collaboration with other disciplines, industry, and student interest. As a learning activity, it offers the chance to develop new areas of study emerging from bottom-up interests and encourages flexibility and failure in a way that traditional teaching delivery cannot risk.

In this paper, I shall explain what it involves, its risks and its advantages. I shall do so by outlining the theory, illustrating it by a mini activity I held in Malta and discussing its risks, opportunities and how it fits the new education strategy.

Caveats:

- been ill, so pretty informal;

- My discipline is philosophy, there is no necessary reason that the facilitator be from a philosophical or similar theoretical/critical position, but I shall present from that perspective. (There might be, though, a reason why philosophy is an appropriate “point of view” of facilitation!)

- Interdisciplinary depends on a community of learners and not an individual polymath

Slide 2 (Collaboration)

University and learning is organized into a system of autonomous disciplines. These are distinguished by different ontologies/vocabulary (the set of items which can play an explanatory role: atoms in physics versus intentions and beliefs in (some) social sciences), epistemologies/(register/discourse??) (the set of events or items which can play an evidential role: observed phenomena in anthropology, semiotic code/structure in cultural studies) and logic/grammar (the set of rules that govern the associations, relation and force of statements made about the ontologies and epistemologies (arguments from analogy, deduction, induction, arguments from authority in theology). These elements as a whole constitute what I would call the dialectic of a discipline (not language, I want to preserve that term). If you do not use the correct terms, in the correct way then you are excluded from a discipline for talking nonsense or doing something else. You are not “allowed in” as a free and equal participant unless you agree to these fundamental presuppositions of a discipline.

Risks of interdisciplinary studies (slide 3)

The analogy for interdisciplinarity given what I have said about differing ontologies, epistemologies and logic/grammar is that all the disciplines are playing games but these games are different. However, the new educational and learning landscape encourages interdisciplinary studies, yet to just throw two disciplines together is like us having two share the chequered board, but one is playing chess and the other draughts and a third Pokemon. Intuitively, the results of the encounter may be fun, interesting but is ultimately frivolous and chaotic. Student work or research produced in this manner is always already suspicious, not serious and so on. (Interesting question to be asked here about the centre and the periphery; the orthodox and the radical.)

And that highlights the risks of interdisciplinary studies:

- We have a model of individualism, so that one person, an agent possesses the outcomes the knowledge. This is due to our structural commitment to intellectual property rights and the modern individual agent of moral responsibility. Now, I have a series of arguments and the theoretical, philosophical level why this is a descriptive error, but a normative necessity. I can’t really go into that here – it is another, fundamentally disciplinary talk – but I basically hold that it is a normative requirement but has been overexpanded and conflated with an economic account of agency. This sets up a real commitment to “proper” team learning and a facilitator needs to spend the first few sessions building a community of toleration;

- Space and time. Structure of our learning, accreditation, assessments. Staff time. That is why informal, impromptu encounters – hybrid, in cultural spaces (museums, coffee shops), virtually and so on.

- Cultural barriers and translation. Different disciplines speak different languages; We all think our language is privileged (reveals the truth) and others are either derivative, inferior or obfuscatory. This is if you like similar to a literary versus science approach. Literary worlds can bring up a problem nicely but only science is the proper way to talk about the object (novels about time travel are interesting but not knowledge!). Certain languages are privileged. In the UK, this is science. In the Middle Ages and other cultures, it is theology. And so on. Underneath all this is the idea there is only one game to play, all others are knock-off versions. Only one truth and only one way to express it – again another fundamental proposition that inhibits proper team learning. One I could again talk quite a long time about (relativism, human interests and so on…) What I would say is that we ought to open to the pluralism in both truth and languages that express that truth (but with a commitment to the propriety of dialects/discourses).

- Also, UG students want a traditional degree with a traditional title (and one cannot teach interdisciplinary unless one is advanced in a discpline!)

- Personal motivation. Why do we do this? Why should students? Some lecturers do not want to teach interdisciplinarity and that is correct, you cannot have the inter without disciplines to bridge so a large part of university must be devoted to established disciplines. Again, seems to be derived from our overly evaluative approach to learning: is there an exam question on this? Can I publish an article (which journal, REF hates it)? Answer here is that a) participation is a good in itself – to learn is an activity worth doing (a washing machine can wash my clothes, but ceramics…) and learning new things, even for lecturers is pleasurable; and b) engages with “reality” — students/academics step out of their closed silo and engage with others, productions of a different kind, engagement with public – learn skills of communication and “translation” and with contexts that have not yet or cannot find a natural disciplinary home (sustainability, AI & data, health, ageing – sound familiar?)

So, we can delineate an ethical approach to interdisciplinary encounters, what I would call the language level. Go back to the game. If we play chess, the aim is to win and I can be strategic (Faye Dunaway in that film! Seduce you, distract you) but to play a game is to commit to not cheating. One cannot win through cheating only give the impression of winning – move a piece, shooting you… This is the level of a shred, universal formal language that as learners (and I might argue humans) we all commit to:

- Step back from the immediacy of one’s own discipline

- Listen to others with openness and toleration

- Replace truth with propriety

These all stem from a fundamental commitment to the ethical equality and autonomy of all participants. Mono-disciplinary studies exclude from their inception (one must be an expert or becoming an expert to participate).

So how to do this (slide 4)

Explain the approach and how it meets the above requirements.

- Context-based (water, AI, art)

- Sharing, differences (learn about other disciplines, listen and open, participants teach others, disseminate to non-experts)

- Personal engagement, disciplinary identity (aware of the worth of one’s own discipline, what it does best where it is most appropriate)

- Division of labour (recognizes contribution other disciplines make)

- Exchange of theory and knowledge (learning in a community, social setting)

- Collaborative production (blogs, films, public conferences, public engagement – not an exam or a simple essay here; decide how best to share the knowledge encountered, discovered, made; become aware of the medium/message problem)

Example in Malta (Slide 5).

Eight learners mostly mature (24—45), studying: Psychology, Youth and Community Studies, education and social work.

Outcomes – why do this (slide 6)

- Proper team teaching (not just a collection of individuals, but academics trying to design a course bottom up whilst doing it, teaching together not parallel (my experience of lit and phil) – may lead to new disciplines (think of sound studies, archeology and physics).

- Truth is put on hold for propriety (commitment to pluralism and the democracy of learning)

- Teaching each other; learning together (the community of the university – equality)

- Collaborative productions and student outcomes (different and public facing encounters that lead to new disciplines, new funding opportunities, engage students who feel a sense of ownership in what is being produced by the university together).

- Equality of learners (commitment to the university or what i have called the Language of learning).