By Christinna Hazzard and Filippo Menozzi

How does world literature contribute to the debate on decolonising the curriculum? World literature can put a new spin on the meaning of “decolonising” because of its dual critique of monolingualism and class blindness in contemporary academia. Indeed, world literature means linking the teaching of non-canonical works, including texts in translation, to an incessant critique of global unevenness, class privilege and economic exploitation. Accordingly, world literature can offer precious tools to resist the undervaluing of the humanities today. Without renouncing its oppositional vocation, it can make literary pedagogy inclusive, relevant and empowering.

The idea that literary studies, and the arts and humanities in general, are threatened by chronic underfunding and systematic undervaluing in our currently political and economic climate is by now well versed. World literature, as field of study and theoretical paradigm, has recently been brought into discussions around the validity and purpose of English studies in a world that is supposedly fully globalised and in an academic and political environment that, with its emphasis on profitability and value-for-money above all else, is increasingly hostile to the arts and humanities. In our view, a world literature rooted in cultural materialist theory offers a valuable and timely contribution to the current need and desire for global perspectives in literary and cultural studies, and has the potential to do so without compromising on the needed critique of our current political and social order, including the important task of decolonising the curriculum.

In this post we will focus on the challenges and possibilities of teaching world literature as part of an English studies programme. These reflections are based on our experience of teaching world literature at Liverpool John Moores University (LJMU). Our third-year ‘World Literature’ module aims to reframe the study of English by drawing on a concept of world literature developed by literary critics such as Franco Moretti, and the Warwick Research Collective. This particular concept of world literature should not be seen as a new canon: rather, world literature is a system, a way of embedding the study of literature in the complex economic realities of the twenty-first century. The questions we raise in the module can be aligned with the general aim of decolonising the curriculum, as we propose international authors from minority and non-privileged backgrounds. However, world literature can put a new spin on the debate and help reimagine what we mean when we talk about “decolonising” the study of literature.

Translation: avoidable or necessary?

In our experience, there is a deep suspicion within English studies around teaching texts in translation, underpinned by an assumption that something will always be lost in translation. As multilingual academics, we, of course, appreciate the satisfaction of working with literature across several different languages. However, this is not always an option available to our primarily monolingual students. In fact, one of the problems with debates discouraging the use of literary texts in translation, is that they often fail to adequately account for the complex politics of language in spaces where majority languages are not spoken. Certainly, in the Nordic region, which is the focus of the research of one of us, translation is unavoidable in the production and circulation of literature because the national literary canons are, quite simply, smaller, and often spill over national borders. This blurring of national canonical boundaries is itself a reflection of the region’s colonial history, including, for instance, the fact that Danish was the official language of the Faroe Islands until 1948 and Greenland until 2009. In both countries the revival of national languages was central to national independence movements, which necessarily involved translating foreign works of literature into Faroese and Greenlandic.

It is, then, a reflection of continued cultural hegemony of English, which is itself, of course, the result first of British and now American imperialism, that translated texts play such a small part in our literary culture. When teaching world literature to our students at LJMU, we found that exposing students to texts in translation invited them to reflect on the parameters of their subject by encouraging debate about what is included and excluded in the broad category of English Literature, and that discussions about the importance of decolonising the curriculum followed. If we want a curriculum that is truly decolonised and global in scope, reading in translation is therefore necessary, but we need to teach students how to approach translated texts, for they often lack the confidence to read and write about texts that deal with non-Anglophone cultures.

Decolonisation: ideology or critique?

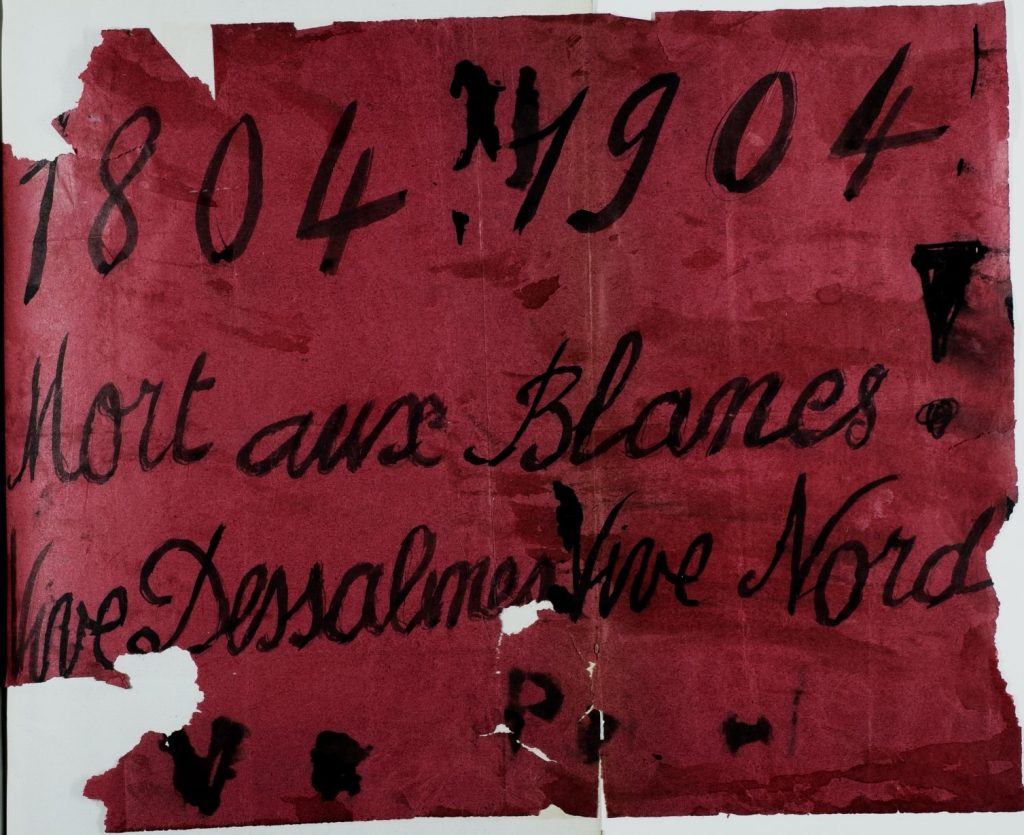

Teaching translated works is a most productive and valuable starting point for linking world literature to the politics of decolonising the curriculum. It shows that ideas and narratives expressed in other languages can be highly translatable and relevant to students in the UK. Furthermore, our experience of teaching non-canonical texts, including works in translation, in a non-Russell Group, ex-polytechnic university can suggest many issues that headlines about decolonising English at Oxbridge have so far dramatically overshadowed. Indeed, the momentum of decolonising the curriculum should not be exhausted by the agenda of cultural diversity. Rather, it should challenge systemic inequality, shifting the focus from the individual and singular towards a more sustained engagement with the structural and the social. In contrast to other ways of studying English, world literature emphasises how texts are entangled in a global supply chain that enables the circulation of capital and commodities. It reveals the dark backstage of oppression of workers, communities and environments that makes our consumer economy possible. Against facile celebrations of multicultural tolerance or success stories of elite migrants, world literature involves an unrelenting focus on the exploitation, injustice and unevenness at the heart of our globalising world. Most centrally, teaching world literature in an ex-polytechnic can illuminate how the question of social class cannot be overlooked in attempts at contesting privilege and hierarchy. Thus, our current syllabus includes a study of NourbeSe Philip’s Zong! (2008). In our module, we propose this text within a wider reflection on Liverpool and its place in a global shipping industry, linking it to pressing concerns about slavery and finance capital. In a ‘World Literature’ module, teaching about the legacy of the 1781 Zong massacre can be a way of discussing the politics of representation in relation to the commodification of human bodies and the exploitation of workers. It is also a way to remap the North-West of England in the wider frame of global capitalism and to find resonances across generations of workers from around the globe.

Teaching world literature to students from diverse and non-privileged backgrounds has taught us to make our curriculum relevant and empowering, mirroring the civic mission and the values of equality and inclusivity of our institution. In much the same way in which the fight for gender equality needs to contest the rise of neoliberal, corporate feminisms, so world literature needs to expand our consciousness about privilege. In an era of student debt, anxieties about job security and the growth of an academic precariat, world literature is the best way to reintroduce questions about cultural production, institutional critique, and social unevenness.

World literature can give the idea of “decolonising the curriculum” a new, revitalising tone: instead of mere politics of recognition and admittance, entry into the mainstream or diversification, decolonising should equal an incessant work of critique and the unlearning of academic race and class privilege. Decolonising should involve putting economic inequality and class domination back into the agenda. In an era of planned undermining of the humanities, world literature prepares us for strategies of resistance and opposition that are urgently needed to protect the future of our discipline and of our communities.

[Christinna Hazzard is sessional lecturer in the Humanities at Liverpool John Moores University. She has recently had a chapter on “Nordic Noir and the Postcolonial North” published in Noir in the North (2020) and is preparing a monograph proposal for her doctoral thesis titled Semi-Periphery Realism: Nation and Form on the Borders of Europe.]

[Filippo Menozzi is lecturer in world literature at Liverpool John Moores University, where he is also director of the MA English Literature. He is the author of Postcolonial Custodianship (2014) and World Literature, Non-Synchronism, and the Politics of Time (2020), and editor of a special issue of New Formations on Rosa Luxemburg.]