By Carrie Poon

Taiwan has a very complicated history of colonisation, but like many East Asian societies this history fits uneasily in current discussions of postcolonial and decolonial studies. Ever since the Portuguese gave Taiwan the name ‘Formosa’ (meaning beautiful), this island underwent a succession of five colonisers, beginning with the Dutch (1624–1662), the Spanish (1626–1642 in northern Taiwan), the Cheng family from China (1662–1683), the Qing Dynasty of China (1684–1895), and the Japanese (1895–1945). In addition, we can further debate whether the Kuomintang’s (the Nationalist Government of China; hereafter KMT) 1949 retreat to the island – after being defeated by the Communist Party in the Chinese civil war – can be seen as another colonisation. If the simple definition of a colonial regime is the rule of outsiders for their own benefit (Jacobs 2013: 569), and if colonisation is a form of domination, exploitation and a process of cultural transplant (Horvath 1972: 46), then the KMT’s self-proclaimed status as legitimate successor of the Japanese as ruler of the island, their brutal suppression of native Taiwanese people, and the prioritisation of Mandarin over other local dialects would suggest that the KMT are indeed colonisers. Furthermore, given that the KMT imposed a 38-year martial law and remained the only ruling party until the late 1980s, it seems impossible to ever imagine how Taiwan could start to decolonise itself. Where should one start?

The Complexity of Post-Japanese Taiwanese History

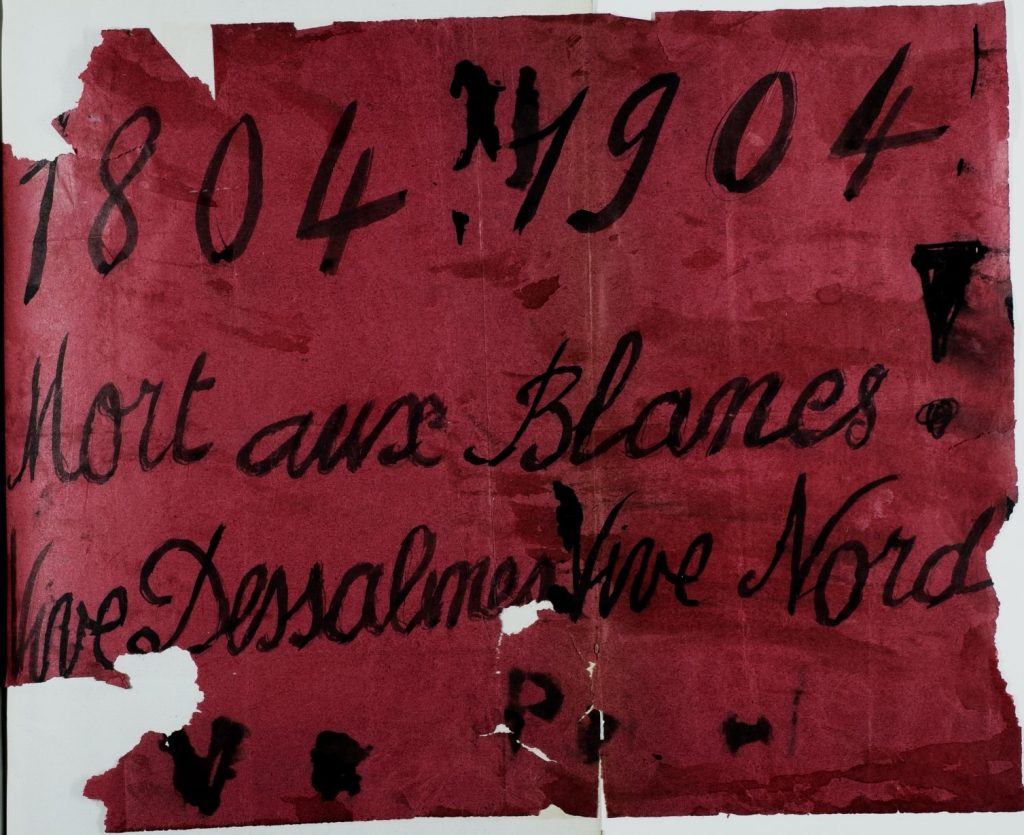

As a researcher and teacher of East Asian Cinema, I will focus on the period of post-Japanese colonisation, because among all the former colonisers, the Japanese colonial regime left the most profound influences on Taiwan society. Taiwan became a Japanese colony under the Treaty of Shimonoseki (1895) after the Qing Dynasty of China was defeated in the First Sino–Japanese War (1894). During this period, the Japanese implemented the kōminka (Japanisation) movement, which successfully instilled pro-Japanese sentiments among the educated upper class Taiwanese elites. When the Japanese colonial rule fell at the end of the Second World War, decolonisation did not happen in Taiwan, for then came the KMT from mainland China, which monopolised the top positions in the governance of the island. Widespread discontent against the KMT even generated nostalgic feelings for the Japanese colonial past among the natives. Scholar Chen Fangming for one sees it a recolonisation project to re-educate former subjects of the Japanese Empire into new citizens of the Chinese republic (Scruggs 2015: 32). Instead of decolonisation, a residual Japanese colonial identity was revived among the native Taiwanese when they were humiliated by the mainland recolonisers (despite sharing the same ethnic origin), ridiculed in the high-handed recolonisation process of the KMT, and their native tongue of Taiwanese Hokkien suppressed in favour of Mandarin.

A series of domestic and international setbacks in the 1970s further bogged Taiwan down: in 1970 the Diaoyu islands were returned to Japan; in October 1971 Taiwan withdrew from the United Nations; in 1975 the political patriarchal figure President Chiang Kai-shek passed away; and in 1979, diplomatic relations between the United States and communist China resumed. However, the continuous loss of international recognition and the waning power of the KMT regime brought hope to Taiwan. Politically, people were increasingly vocal in their demand for political liberalisation. Culturally, Taiwan’s xiangtu (‘native soil’) literature regained attention after being long suppressed by both the Japanese and KMT regimes. Xiangtu literature attempts to create a distinctive form of Taiwanese identity different from the mainstream Chinese national identity promoted by the KMT. For the first time after years of tight Japanese and KMT control and censorship, Taiwanese writers enjoyed the ‘luxury’ of seeking a representative literature that would realistically reflect the new social, economic and political conditions of a rapidly modernising society. The decolonisation of Taiwan started, I believe, with this nativist literary movement that first appeared in the early 1970s and continued to play an important part in the gradual process of cultural democratisation in the 1980s.

Cultural Democratisation and Taiwanese Films

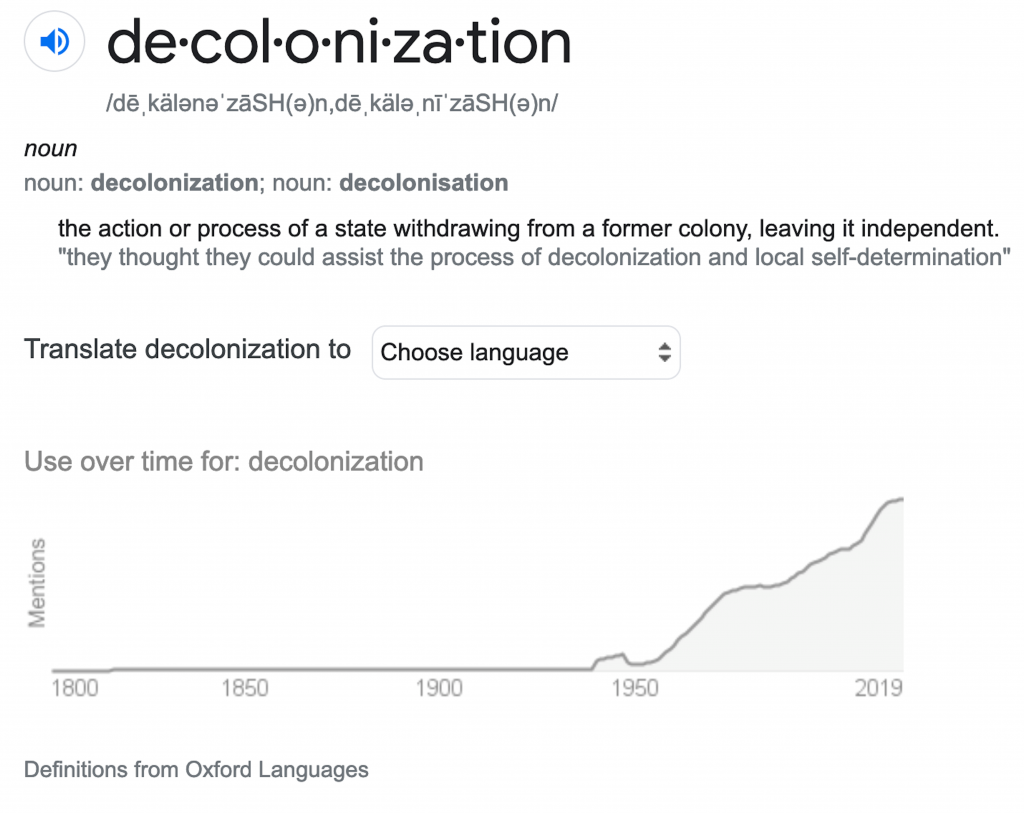

Cultural democratisation refers to the long-term process whereby diverse cultural ideas previously not permitted are allowed to be produced and promoted (Rawnsley 2016: 373). I see much overlap with the core spirit of decolonisation, where the prefix ‘de-’ invites a revised understanding and to ‘unlearn’ certain knowledge and structures of knowledge (Mistry 2021: 2). A few years before the lift of martial law in July 1987, a prominent urge to construct a local Taiwanese identity began to gather momentum. Alongside xiangtu literature, the Taiwan New Cinema (TNC) movement also emerged as a wave that manifested a distinct Taiwanese cultural and historical identity which was non-existent before the late 1970s. Although the TNC directors at the time may not have been directly aware of the idea of decolonisation, their themes and aesthetics in every way expressed their resistance to any form of colonisation, be it institutional or ideological. With the increasingly relaxed restrictions on media in the years leading up to the end of martial law, Taiwanese cultural and media workers could freely and properly conceptualise Taiwan’s identities and historiography at last. For example, local dialects were frequently used in TNC films alongside Mandarin – a sign that these films expressed not only an awakening Taiwanese identity, but also a subconscious act of decolonisation.

TNC films also reconceptualised the historiography of Taiwan through their portrayal of Taiwan’s colonial past under Japanese rule. For example, director Hou Hsiao-hsien, one of the flagbearers of TNC, seized the opportunity to exploit the suspension of rigid ideological control and made his first post–martial law film A City of Sadness (1989) toexplore the Japanese colonial period, which had been off limits previously. Set in the 1940s, the film represents Taiwanese identity as a kind of ‘helpless child’, a metaphor traced back to Wu Zhuo-liu’s most influential novel Orphan of Asia (1945) which highlighted the ambiguity and tension inherent to being Taiwanese. In Hou’s film, Wen-heung, the eldest brother of the Lin family and a business owner with a gangster background, finds his livelihood threatened by the politically connected and more competitive Shanghainese gangsters from the mainland. Two out of his three younger brothers are sent to the Philippines and Shanghai respectively to fight for the Japanese colonial regime during the Second World War; while the elder of the two never returns, the younger, Wen-leung, suffers from shellshock after the war (Fig 1). Because they have been sent to fight against the Chinese on behalf of the Japanese, the newcomers in Taiwan from the mainland see them as traitors. The youngest brother Wen-ching, a deaf and mute photographer, is accused of supporting the native Taiwanese after an anti-KMT uprising. He is taken away for interrogation and is never to be seen again (Fig 2).

As Wen-heung bitterly spells out in the film, ‘the Taiwanese are the most pitiful. Nobody cares about us, nobody loves us, everyone tries to oppress and humiliate us’ (Fig 3). The story of the Lin brothers is a refraction of Taiwan’s complicated colonial trajectory, and Hou uses a number of remarkable cinematic techniques to underscore this. First, he uses different languages to highlight the identity conundrum faced by the Taiwanese. With Japanese being replaced by Mandarin as the official language under the KMT regime, the film’s main narrator, Wen-ching’s young wife Hiromi (Fig 4; note her Japanese name), ironically uses the local Taiwanese dialect to report events and express her own emotions. As such, the KMT’s imposition of mainland Chinese culture and reimagination of Taiwan’s historiography are directly challenged by the voiceover of a native Taiwanese woman with a Japanese name who reports history from her point of view. Moreover, Hou’s signature technique of ‘long shot–long take’ enhances the objectiveness of his observation on Taiwan’s colonial history. By allowing ‘certain real situations to naturally unfold themselves in the film’ (Yeh & Davis 2005: 157–158), Hou invites the audience to question how some political concepts are normalised and institutionalised by colonial or dominant power structures. Through this film, Hou helps initiate an ongoing process of constructing a localised Taiwanese identity, precisely by combing through a brutal colonial history hitherto unexplored under the period of martial law (Chiang 2013: 30). It is without doubt a film of decolonisation par excellence.

Although the TNC is generally believed to be a short-lived movement taking place between 1982/83 and starting to phase out shorty after 1987, the works of the first generation TNC directors such as Hou Hsiao-hsien and Edward Yang still have great impact on the ensuing generations of Taiwanese directors, and the ongoing process of Taiwan’s decolonisation is still a prominent theme in post-TNC films. The still-coalescing multi-ethnic and multicultural Taiwanese identity is depicted, for example, in Wei Te-sheng’s recent trilogy – Cape No 7 (2008), Warriors of the Rainbow (2011) and Kano (2014) – which features a non-dichotomising attitude that does not portray the successes and failures of Japanese colonisation in black-or-white terms. As Jyoti Mistry contends, decolonial processes should neither be bound to the geographical space of the colony nor to the time before, during or after colonialism (2021: 2). As long as Taiwan cinema exists, the long revolution of decolonisation will never cease.

References

Horvath, R. (1972) A Definition of Colonialism. Current Anthropology 13 (1), pp. 45–57.

Jacobs, J. (2013) Whither Taiwanization? The Colonization, Democratization and Taiwanization of Taiwan. Japanese Journal of Political Science 14 (4), pp. 567–586.

Mistry, J. (2021) Decolonizing Processes in Film Education. Film Education Journal 4 (1), pp.1–13.

Rawnsley, M. (2016) Cultural Democratisation and Taiwan Cinema. In: G. Schubert, ed. Routledge Handbook of Contemporary Taiwan. London: Routledge, pp.373–388.

Schiwy, F. (2007) Decolonization and the Question of Subjectivity. Cultural Studies 21 (2–3), pp. 271–294.

Scruggs, B. (2015) Translingual Narration: Colonial and Postcolonial Taiwanese Fiction and Film. Hawaii, Hawaii University Press.

Yeh, E. & Davis, D. (2005) Taiwan Film Directors: A Treasure Island. New York: Columbia University Press.

Yeh, E. (2005) Poetics and Politics of Hou Hsiao-hsien’s films. In: S. Lu & E. Yeh, eds. Chinese-Language Film: Historiography, Poetics, Politics. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, pp. 163–185.

Filmography

A City of Sadness (1989) Directed by Hou Hsiao-hsien. Era Communications (International rights).

Cape No 7 (2008) Directed by Wei Te-sheng. Buena Vista Distribution.

Kano (2014) Directed by Wei Te-sheng. Vie Vision Pictures Co., Ltd.

Warriors of the Rainbow (2011) Directed by Wei Te-sheng. Vie Vision Pictures Co., Ltd.

[Carrie Poon is a 4th-year doctoral candidate in the School of Modern Languages, Newcastle University, working on her PhD project on Taiwanese director Edward Yang’s films and their representation of masculinity. She currently teaches on an undergraduate module on East Asian Cinema which explores the culture, history and identity of different East Asian cities through their films.]