Blog post by Stephanie Newell, with an introduction by Neelam Srivastava

Introduction

Neelam Srivastava

This blog post by Steph originated out of an event I organised in May 2021, hosted by the Newcastle Postcolonial Research Group. Entitled ‘Postcolonial Pedagogy and the Task of Decolonisation‘, it featured two globally eminent scholars of postcolonial studies and African literature: Stephanie Newell and Ato Quayson. Steph was recently Leverhulme Visiting Professor in the School of English at Newcastle University (2019–2021). I invited Steph and Ato to speak not only as pioneers in the field, but also as hugely experienced teachers of postcolonial literature and theory. Decolonisation and diversity are by now buzzwords in Higher Education: both at Newcastle University and at universities around the world, ‘decolonising the curriculum’ has become a mantra. In many ways, of course, this is an extremely welcome development; a global public conversation is finally taking place around the need to rethink the teaching and transmission of western cultural heritage. Its influential reach is an acknowledgement that there is work to be done on provincialising and decentring the supposed ‘universality’ of the human subject within and across the disciplinary formations of university education. At another level, though, ‘decolonising the curriculum’ partakes in the slightly hypnotic and uncritical (or acritical) aspect of all mantras: it thus risks morphing into an ideological party line rather than maintaining a dynamic consciousness of decolonisation as a constant work in progress. The risks inherent in the party line are linked to the uses it is put to: how do we make sure that decolonisation stays faithful to its stated objective, i.e., working towards a collective project of liberation, rather than merely becoming a way to pursue individualistic or identitarian claims within the academy?

The event aimed to examine the intersections and divergences between recent debates on curriculum diversity and the values and principles of postcolonial literary pedagogy, which has long been asking students to think critically about the racial and colonial assumptions structuring academic programmes in the Humanities. The conversation with Ato and Steph centred on their experience of teaching postcolonial literature, from a time when it was still quite marginal to mainstream syllabi, to the current moment, when Decolonising Education has become almost a policy at the institutional level. We wanted to ask these scholars whether the inclusion of postcolonial literature automatically achieves the decolonisation of the curriculum or whether new forms of cultural subalternity and canonicity enter into play. How can university teachers negotiate students’ demands for the recognition of gendered, racialised, and economic oppression with the need to emphasise that there are often competing notions of marginality? Subalternity is a relational, never an absolute identity, and thus the goalposts are ever mobile. The conversation on screen evolved in fascinating and unforeseen ways, with both scholars sharing anecdotes and insights about their pedagogic experiences. The participants also chimed in with their own observations and questions; many said they were there to learn, as decolonisation was still a recent word for them. After the event, some wrote to me asking for reading lists and tips on how to decolonise a research topic without an apparent point of entry (for example, someone wanted to know how they could research the use of building materials in Indonesia from a decolonising perspective). This awareness was of course the necessary starting point for the educational journey of decolonisation. As one participant remarked, decolonisation is always unfinished, never complete, a constant effort to uncover and dismantle the founding stereotypes and institutional biases at the heart of what we call knowledge.

The Task of Decolonisation

Stephanie Newell

I started my lecturing career in 1994, just as the first two major anthologies of postcolonial theory arrived on the scene.[1] Critical race theory, Pan-Africanism and theories of colonialism and anticolonialism had been growing in impact within universities in the Global North throughout the second half of the twentieth century, but the appearance of these two anthologies put postcolonial studies firmly on the syllabus as a mainstream, or at least unavoidable, sub-discipline in English departments.[2] In the UK, the old ‘Commonwealth Literature’ syllabus, with its canon of Anglophone literary texts, was rapidly reshaped into the new field of postcolonial studies.

Nearly 30 years later, as the field of postcolonial literature gives way to world literature, I wonder what that institutional moment in the mid-1990s – better phrased, perhaps, as that moment of institutionalisation – produced in terms of epistemological breaks and complicities? The anthologies gave teachers and students a wide range of tools for recognising how imperialist and racist power operate structurally, institutionally, archivally and historically. Through the anthologies, an awareness of postcolonial literature and theory slowly filtered into English literature courses, inspiring discussions about the necessity for the diversification of the curriculum and giving visibility to non-Eurocentric perspectives, albeit often parked in ‘postcolonial’ corners of the syllabus rather than on foundational courses.

But a question remains: to what extent has the mainstreaming of postcolonial literature and theory in universities from the mid-1990s onward, with all the critical ways of thinking these works inspired, helped to move our departments and our universities in the direction of ‘decolonisation’? Without a doubt, the discipline of postcolonial studies has helped to diversify the syllabus, but how has it contributed to the ‘task of decolonisation’, that is, the removal of Eurocentric power structures, the diversification of knowledge production and the creation of spaces to take action against systemic racism and other forms of prejudice (see Cleary 2021; Bhambra et al. 2018; Gopal 2021)?

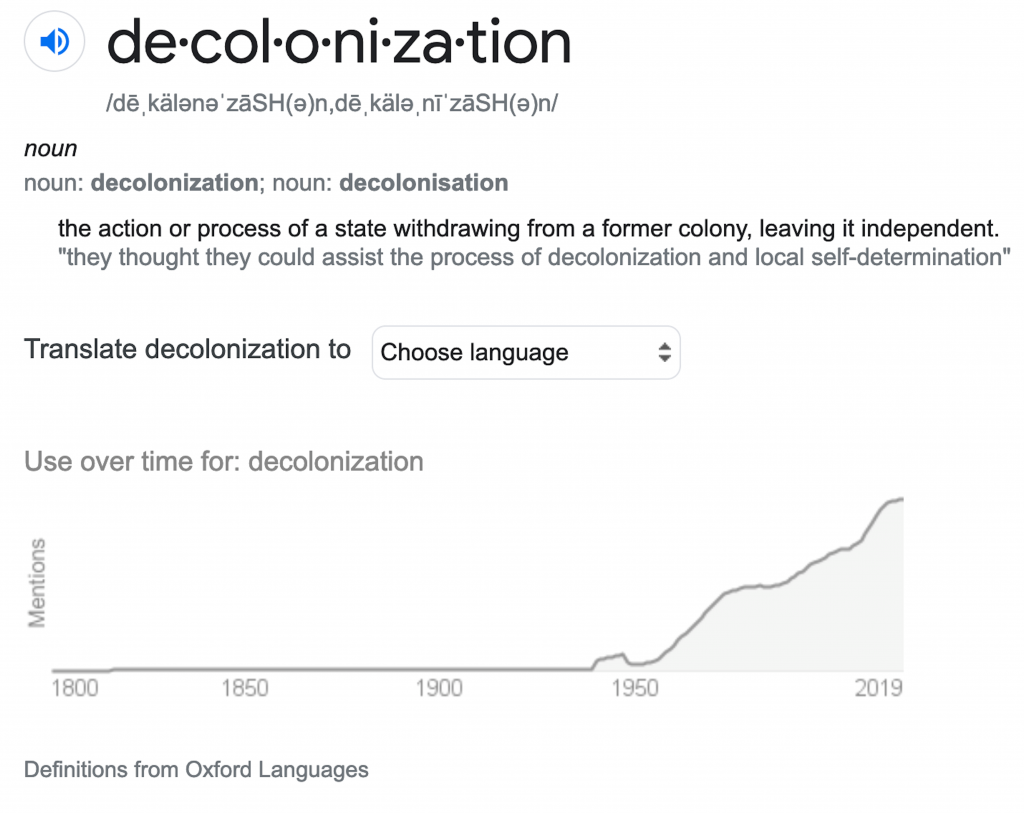

The Oxford dictionary definition of decolonisation is ‘the action or process of a state withdrawing from a former colony, leaving it independent’ (Oxford Languages, OUP). The Oxford Languages data graph shows no usage of the word up to about 1940, and then a steady rise from 1955 onward (see figure). The real increase in usage occurred long after ‘the actions or processes of states withdrawing from former colonies’ between the late 1940s and early 1960s. Usage of the word climbed exponentially in the 2000s and continues on an upward trajectory. This is a term that has gained popularity as a consequence of its metamorphosis from the definition of a specific political process involving foreign territories into a powerful metaphor for recognising and transforming power relations in metropolitan institutions. In its contemporary usage, decolonisation still means ‘actions or processes’ involving the reconfiguration of institutional spaces, but what is being ‘withdrawn’ is more difficult to identify than in dictionary-definition decolonisations. Contemporary decolonisation processes involve critical, deliberative, space-clearing gestures within institutions by and on behalf of historically excluded groups, as well as the recognition of how racism and other exclusionary forms of power operate through multiple institutional spaces – ranging from schools to police forces – as well as through implicit and unconscious prejudices (see Bhambra et al. 2018).

In a recent article on ‘The English Department as Imperial Commonwealth’, Joe Cleary points out that English departments have tended to respond to calls for diversification by expanding their scope and provision rather than by questioning their power structures and histories. As a consequence, he argues, they adopt ‘additive strategies’ by which they ‘retain as much as possible of the core curriculum while opening new subject options and degree pathways’ (2021, p. 166).

While the ‘additive’ type of expansion is a good example of diversification, it falls short of decolonisation. To illustrate some of the problems with the diversification of the curriculum without an accompanying institutional decolonisation, I want to recount a teaching experience that illustrates some of the ways in which the diversification of the syllabus may produce the opposite of what it sets out to promote unless it is accompanied by an explicit critique of broader problems of structural racism and Eurocentrism.

In the autumn of 2017, the English Department at Yale introduced a new foundational course, ‘Readings in Comparative World English Literatures’. The initial course blurb read:

An introduction to the literary traditions of the Anglophone world in a variety of poetic and narrative forms and historical contexts. Emphasis on: developing skills of literary interpretation and critical writing; diverse linguistic, cultural and racial histories; the politics of empire and liberation struggles. Authors may include Daniel Defoe, Mary Prince, J. M. Synge, James Joyce, Claude McKay, Jean Rhys, Yvonne Vera, Chinua Achebe, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, J. M. Coetzee, Amitav Ghosh, Salman Rushdie, Alice Munro, Derek Walcott, and Patrick White, among others.

By the standards of postcolonial literary study in the UK, our reading list was conservative and contained too few writers of colour. Within a few weeks of the start of semester, however, a reporter for the right-wing student media outlet, the College Fix, ran a highly critical piece on the ‘decolonization’ of the Yale English degree programme, arguing that this course enabled undergraduates to complete an English major without having to study Chaucer or Shakespeare.

On the same morning as the College Fix piece appeared, I received an unsolicited email, also on the theme of decolonisation (the senders’ names and email address have been removed):

Subject: Prospective student

Dear Ms. Newell,

Just a short note to thank you for ‘decolonizing’ your English department. My brilliant high school sophomore daughter was, god knows why, actually considering Yale as one of her college picks next year. However, your recent actions concerning the English Department’s curriculum eliminated that choice for her, and my wife and I are eternally grateful. Our daughter, who reads (and treasures) all those hate-filled white demon writers, still understands and values the inestimable contributions those dead white men made to Western civilization, so there’s no need now for us to lose her to your Soviet-style cultural genocide—a manner of self-righteous, self-hating lunacy that we know is echoed throughout Yale’s various educational departments.

Sincerely: we couldn’t be more grateful to you.

The man and woman who signed this email also contacted the Press Office, and one of them phoned the Yale English Department administrator to communicate the sentiments expressed in the mail. As I was not permitted to reply directly to the correspondents, I passed their message to the student-run Yale Daily News, which included it in an article on decolonisation debates in the English Department.

With all this going on, the eighteen undergraduates enrolled in ‘Readings in Comparative World English Literatures’ certainly felt as if a spotlight was focused on them. This may have contributed to an incident toward the end of semester, when a group of four or five white American women, one of whom had been especially vocal on the topic of global women’s rights, intervened in the discussion of Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children to argue that the novel was evidence of Rushdie’s patronising and stereotypical ideas about Indian women, who he deprived of agency and depicted as inferior to men.

There were four students of colour in the class, one of whom, who identified as Southeast Asian, argued vociferously against the way these students appeared to be ‘speaking for’ Indian women in their critique of Rushdie. This student was later called a ‘misogynist’ by the most outspoken of the critics, although not in my hearing. Meanwhile, one of the other students of colour, who identified as Southeast Asian-American, interjected to say that Indian women did not have gender equality either at independence in the late 1940s, when Midnight’s Children is set, or in the early 1980s, when Midnight’s Children was published, so Rushdie should not be obliged to represent them as equal. She was shouted down. I attempted to problematise both sides of the argument: should Rushdie’s female characters be regarded sociologically at all? What were the problems with a reflectionist view of literary texts? Were there ways we could think about gender stereotypes, representation, postcolonial masculinities and discursive power without requiring ‘real’ Indian women as referents? But the students who identified as liberal feminists became increasingly vociferous for the remainder of the session while the students of colour became silent.

Four years on, I have some unresolved questions about this classroom altercation. Is it an example of the ways in which the diversification of the syllabus does not equate to institutional decolonisation (in spite of the claims of conservative commentators)? In terms of the problematics of identity politics, how significant is race compared with class, political persuasion, national identity and gender to understanding what happened? A handful of white liberal American women seemed to have taken the diversified foundational syllabus and filled the space it had cleared in the curriculum with what they understood to be universal truth–claims articulated on behalf of women globally. I wonder how different the encounter would be now, in the wake of the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement?

The following week was the final week of semester, giving very little time to address the fall-out from the Rushdie class. I gave students Achebe’s essay from Morning Yet on Creation Day (1975) in which western readers are urged to ‘cultivate the habit of humility appropriate to [their…] limited experience’ (1975, p. 9). I also brought Chandra Talpade Mohante’s ‘Under Western Eyes: Feminist Scholarship and Colonial Discourses’ (1988) and Sara Suleri’s ‘Woman Skin Deep: Feminism and the Postcolonial Condition’ (1992) to everyone’s attention. (Both of these essays are reproduced in the postcolonial studies anthologies of 1993 and 1995.) In a minilecture on these materials, I highlighted Achebe’s call for western readers to exercise humility, and offered a critique of liberal universalism that concluded with Frantz Fanon’s final appeal, in Black Skin White Masks, to become a person ‘who always questions’ (1967, p. 232). But as the course ended, it seemed to me that the vocal students had not experienced much self-doubt about the validity of their positions.

Clearly, the role of the teacher is crucial in maintaining an environment of individual safety and collective mutual respect where students can question their own and others’ preconceptions reflexively and non-aggressively. Consensus need not – indeed, should not – be a teacher’s objective in seminar discussions within arts and humanities subjects. Many scholars have written about how to create learning climates where individual discomfort can be safely expressed in the context of institutional power hierarchies and structural biases, ranging from Spivak’s powerful arguments for teaching as a decolonial intervention in classrooms in the Global North through to the many publications on anti-racist pedagogy and broader theories calling for agonistic pluralism in the western public sphere (Spivak 1993, Bhambra et al. 2018, Shim 2012, Mouffe 1999).

But in addition to the need for carefully facilitated discussions inside the classroom, the student interventions described above need to be positioned within a cluster of external, institutionally framed conditions arising out of the status of Yale English as a liberal arts department in an elite private university, a department dominated until recently by an adherence to New Criticism and an Old World literary canon, and regarded by many Americans as a bastion of tradition. In this context, the moment of diversification of the foundational syllabus in 2017 can be seen as both an ‘additive strategy’ that expanded the syllabus without addressing the systemic problems that accompany the ‘task of decolonisation’, and also as a ‘decolonising’ challenge to the methods and parameters of English Literature in elite American universities, especially as perceived by people outside the department who disapproved of the wider debates about curricular diversification.

Six weeks after the end of the course, the student who had been shouted down wrote an article for the Yale Daily News. I was intensely uncomfortable reading her account of our class on Midnight’s Children. In it, she indicated that institutional Eurocentrism had prevented a diversified syllabus from becoming much more than a tool for American liberals’ assertions of moral superiority over the rest of the world. I felt deeply implicated in the problems she identified.

A large number of further questions come out of this classroom experience, from the practical to the pedagogical, from ‘lived experiences of race’ (to borrow Fanon’s phrase) among students of colour at predominantly white institutions to white liberals’ unreflexive displays of what Emily Apter calls the ‘translatability assumption’: that is, an investment in the idea of a comprehensive world literature that is accessible to all, regardless of linguistic, political, cultural and institutional histories (Apter 2013, p. 347). As Apter argues, the belief system that gives rise to the concept of ‘translatability’ risks ignoring the ways cultural differences cannotalways be made explicit, nor conveyed cross-culturally through the medium of texts. Yet, as Priyamvada Gopal points out in her brilliant recent article, ‘On Decolonisation and the University’ (2021), the idea of cultural incommensurability should be treated with caution because of its danger of reiterating segregationist ideas that work against the articulation of global solidarities and shared anticolonial political agendas. In place of incommensurability, Gopal’s template for decolonising actions involves ‘mutually transformative engagement – between different cultures, traditions, and approaches to knowledge, bearing in mind structural disadvantages and historic power differentials. We might even call this process “relinking”’ (Gopal 2021, p. 20).

English Departments in the Global North have rapidly diversified their curricula in the last three decades, and demands for decolonisation have challenged university management in the wake of BLM. Institutionally, however, we need to think more deeply about the structural transformations we have yet to achieve, and who speaks for whom in this discourse of decolonisation. Gopal insists that decolonisation should not hold the status of a metaphor: it is not ‘a metaphor for social justice’, she argues, because it involves the dismantling of colonial orders through anticolonial critique and activism (2021, p. 15, pp. 13–14). She invites us to conceptualise ‘an anticolonial university … rather than a “decolonized” one’, in order to make visible and repair the gaps in understanding that accompany knowledge production in the Global North (ibid.). In short, Gopal’s proposal for the decolonisation of universities is for a ‘reparative’ project that acknowledges and transforms the ‘harmful conditions’ out of which so much knowledge has emerged in our institutions (17).

Given the contributions of postcolonial writers and theorists over the decades to make visible these ‘colonial’ conditions, some practical questions remain: who constitutes the ‘colonised’ in this more-than-metaphorical discourse of institutional decolonisation, and who is the ‘coloniser’? What are the next steps we should take to achieve a broad, reparative project of decolonisation at our different institutions, and how shall we go about collectively articulating our goals?

References

Achebe, Chinua. (1975) Morning Yet on Creation Day. London: Heinemann Educational.

Apter, Emily. (2013) Against Translation: On the Politics of Untranslatability. New York: Verso.

Ashcroft, Bill, Gareth Griffiths, and Helen Tiffin, eds. (1995) The Postcolonial Studies Reader. London and New York: Routledge.

Bhambra, Gurminder K., Dalia Gebrial, and Kerem Nişancıoğlu. (2018) Decolonising the University. London: Pluto Press.

Cleary, Joe. (2021) The English Department as Imperial Commonwealth, or The Global Past and Global Future of English Studies. boundary 2 48 (1): pp. 139–176.

Fanon, Frantz. (1986 [1967]) Black Skin White Masks. London: Pluto Press.

Gopal, Priyamvada. (2021) On Decolonisation and the University. Textual Practice. DOI: 10.1080/0950236X.2021.1929561

Mohante, Chandra Talpade. (1993 [1988]) Under Western Eyes: Feminist Scholarship and Colonial Discourses. In: Williams and Chrisman, eds. Colonial Discourse and Post-Colonial Theory: A Reader.New York and London: Harvester Wheatsheaf, pp. 196–220.

Mouffe, Chantal. (1999) Deliberative Democracy or Agonistic Pluralism? Social Research 66 (3), pp. 745–758.

Shim, Jenna Min. (2012) Exploring How Teachers’ Emotions Interact with Intercultural Texts: A Psychoanalytic Perspective. Curriculum Inquiry 42 (4), pp. 472–496.

Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. (1993) Outside in the Teaching Machine. London & NY: Routledge.

Suleri, Sara. (1993 [1992]) Woman Skin Deep: Feminism and the Postcolonial Condition. In: Williams and Chrisman, eds. Colonial Discourse and Post-Colonial Theory: A Reader.New York and London: Harvester Wheatsheaf, pp. 244–256.

Williams, Patrick, and Laura Chrisman, eds. (1993) Colonial Discourse and Postcolonial Theory: A Reader. New York and London: Harvester Wheatsheaf.

[Stephanie Newell is Professor of English and Acting Chair of the Council on African Studies at Yale University. Her research focuses on the cultural histories of printing and reading in West Africa, including spaces of local creativity and resistance in colonial-era newspapers. The book project she started while being a Leverhulme Visiting Professor at Newcastle University between 2019–2020 is entitled Newsprint Worlds: Local Literary Creativity in Colonial West Africa.]

[1] Patrick Williams’ and Laura Chrisman’s Colonial Discourse and Postcolonial Theory: A Reader (1993) was swiftly followed by The Postcolonial Studies Reader (1995), edited by Bill Ashcroft, Gareth Griffiths and Helen Tiffin. Williams’ and Chrisman’s volume had fewer, but longer, extracts from major works of theory; Ashcroft et al.’s volume contained a multitude of shorter extracts from diverse sources and genres, several of which overlapped with the first volume.

[2] Noticeably, Routledge (Taylor & Francis) published the majority of new works of postcolonial theory in the 1990s and played a critical role in defining the field.