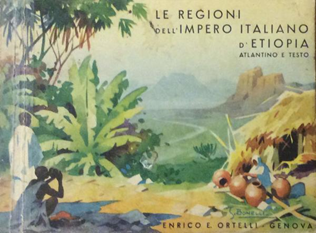

Postcolonial theory, in Italian academia, is a young field of study. Colonialism has similarly received little attention in literature, from both authors and scholars, going almost unnoticed in the public discourse and academia, until recent publications started to address the long-lasting legacy of imperialism and its role in shaping the Italian national identity, especially during the Fascist period. It is almost implausible that the period of Italian colonialism, roughly stretching from 1869 to 1960, has been overlooked for decades since the Second World War and still, regrettably, remains an under-studied area in the Italian academy and a problematic topic in the public and political arena. When that chapter of history is discussed, the tone is apologetic, if not dismissive. Italians still fashion themselves as those who brought development and investment to Africa. Although more limited in both time and space than British or French colonialism, Italian colonialism was a period of massacres, oppression, and racism. It had an unquestionable impact, both in the metropole and in the colonies, that still resonates today. Scholars, especially historians, have started to investigate this impact from the mid-1980s (Giorgio Rochat and Angelo Del Boca), but only in the mid-1990s and early 2000s did postcolonialism as a scholarly field made its appearance in literary studies in Italy.

What are the reasons for this delay? Scholars such as Ruth Ben-Ghiat, Mia Fuller, Derek Duncan, Sandra Ponzanesi, Valeria Deplano, and Cristina Lombardi-Diop have tried to explain the historical, political, and social causes that concealed colonialism from public discussion and academic interest. Most of them are connected to historical factors, such as the absence of mass migrations from the former colonies to Italy and the lack of any trials against Fascist officials who fought in the African territories during WW2; there are also socio–political reasons, such as the myth of Italiani brava gente [good people], which helped to globally re-establish Italy’s reputation as a democratic nation after twenty years of Fascist dictatorship.

In the field of literary studies, Roberto Derobertis, in his short but telling article, ‘Da dove facciamo il postcoloniale?’, examines the consequences of this delay in Italian academia. He suggests that Italian postcolonial studies are founded on ‘missed debates and gaps’, so that the corpus of postcolonial works that is growing in Italy lacks consistency and is reliant on paradigms elaborated in other colonial contexts, such as the Anglophone and the Francophone. For example, Edward Said’s ground-breaking work Orientalism was translated into Italian only in 1991 (Bollati Boringhieri), thus causing a delay to the response to the productive debate engendered by its publication in 1978. Still today, Italian readers and scholars have limited access to well-established works of postcolonial scholars, as only a few texts (and primarily Anglophone) have been translated. Ironically, one of the main theoretical backbones of Said’s work is the thought of Italian Marxist philosopher Antonio Gramsci (1891–1937).

Due to this absence of engagement with postcolonial scholars’ theoretical works, the postcolonial paradigm has never been used systematically to analyse the literary and cultural production in Italy. Indeed, only a few monographs and comprehensive studies have explored alternative readings of Italy as a postcolonial entity and have suggested a coherent theory to apply to the Italian case. Moreover, the authors of these studies often teach or work outside Italy, mainly in the UK and the US, meaning that the departments of Italian studies have failed to incorporate the postcolonial paradigm into their curricula. This reluctance to engage with postcolonial studies has prevented Italian academia from developing an exclusive and well-framed postcolonial theory, specific to the Italian context.

In this scenario, we can clearly identify blind spots and absences in Italian postcolonial studies. There is still much work to do ahead, especially in the fields of literary studies. The analysis of the representation of Africa in Italian literature, but also in newspapers, magazines, textbooks, and other media, has just begun, but is crucial for understanding how the ‘concept’ of Africa, fashioned during colonialism, still persists to this day. Postcolonial studies are also instrumental in re-reading the canon and decolonising it. It is fundamental to show that colonialism, more than forgotten, has been like a ghost, almost invisible but definitively present, in literature and in our every-day life too.

Another way to look at colonialism, which is still largely ignored, is to focus on the former colonies and place geography at the centre of the literary enquiry. Thus far, postcolonial interventions ‘have become so accustomed to thinking of the novel’s plot and structure that […] they have overlooked the function of space, geography, and location’ (Said 1993, p. 84). As in Somalia’s case, we are still missing an exploration of the forms of resistance coming from Somali people during colonialism and its aftermath. Italy, in fact, officially ruled Somalia until 1960, but the relationship between the two countries continued until the beginning of the Somali civil war in 1991. Of this other piece of history, quite exceptional in the postcolonial context, we still know very little, even though the body of works by Somali writers, especially from the diaspora, is growing and, in some cases, has received international acclaim, as in the case of Nuruddin Farah and Nadifa Mohamed. Both these authors show us how the ties with Italy are far from receding and how we should listen to the voices able to speak about a past which has been blotted out from Italy’s national consciousness for far too long.

Recent events (from the European migrant crisis to the death of George Floyd, Black Lives Matter protests and the removal of symbols of colonialism and slavery) had a strong impact both at the global and local level (see, for example, the defacing of Indro Montanelli’s statue in Milan after the statue of slave trader Edward Colston was removed in Bristol). These events have also shown how it is essential, in this particular moment more than ever, to face the past and its legacy, especially for nations such as Italy, which are experiencing a new rise of racism towards those Libyan, Eritrean, Somali and Ethiopian ‘immigrants’ whose migrations are linked to the colonial past and its ongoing impact in the present. Drawing inspiration from Said’s words, what we should do now, as teachers and scholars, is to urge students – and ourselves – ‘to situate [one’s own identity, history, tradition] in a geography of other identities, peoples, cultures, and then to study how, despite their differences, they have always overlapped one another, through unhierarchical influence, crossing, incorporation, recollection, deliberate forgetfulness, and, of course, conflict’ (1993, pp. 331–332).

References and a mini bibliography on Italian colonialism

Ahad, Ali Mumin. (2017) Towards a critical introduction to an Italian postcolonial literature: A Somali perspective. Journal of Somali Studies 4 (1–2), pp. 135–159.

Aidid, Safia. (2011) Haweenku wa garab (Women are a force): Women and the Somali Nationalist Movement, 1943–1960. Bildhaan 10, pp. 103–124.

Andall, Jacqueline, and Derek Duncan. (2005) Italian Colonialism: Legacy and Memory. London: Peter Lang.

Ben-Ghiat, Ruth, and Mia Fuller. (2005) Italian Colonialism. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Chambers, Iain, ed. (2006) Esercizi di potere: Gramsci, Said, e il postcoloniale. Rome: Meltemi.

De Donno, Fabrizio, and Neelam Srivastava. (2006) Colonial and postcolonial Italy. Interventions: Journal of Postcolonial Studies 8 (3), pp. 371–379.

Deplano, Valeria. (2018) Per una nazione coloniale. Il progetto imperiale fascista nei periodici coloniali. Perugia: Morlacchi.

Gnisci, Armando. (2003) Creolizzare l’Europa. Letteratura e migrazione. Rome: Meltemi.

Lombardi–Diop, Cristina, and Caterina Romeo. (2012) Postcolonial Italy: Challenging National Homogeneity. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Mellino, Miguel. (2006) Italy and postcolonial studies. Interventions 8 (3), pp. 461–471.

Palumbo, Patrizia. (2003) A Place in the Sun: Africa in Italian Colonial Culture From Post–Unification to the Present. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Parati, Graziella. (2005) Migration Italy: The Art of Talking Back in a Destination Culture. Toronto: Toronto University Press.

Portelli, Alessandro (1999) Mediterranean passage: The beginnings of an African Italian literature and the African American example. In: Maria Dietrich, Henry Louis Gates Jr., Carl Pedersen, eds. Black Imagination and the Middle Passage. New York, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 282–304.

Sinopoli, Franca, ed. (2013) Postcoloniale italiano. Tra letteratura e storia. Aprilia: NovaLogos.

Said, Edward. (1993) Culture and Imperialism. London: Chatto & Windus.

Tomasello, Giovanna. (2004) L’Africa tra mito e realtà. Palermo: Sellerio.

Virga, Anita, Brian Zuccala et al. (2018) Postcolonialismi italiani ieri e oggi. Special issue of Italian Studies in Southern Africa 31 (1).

[Marco Medugno has recently obtained his PhD in English literature from Newcastle University, with a comparative project on Somali diasporic authors writing in English and Italian. He is currently teaching Fictions of Migration at NCL and working on a project about the reception of Dante in the African Anglophone literary context.]