By Charlotte Pickles

This blogpost was developed from a student essay written for the module ‘Introduction to History, Culture and Society of the Iberian Peninsula’, which is taken by stage 1 and stage 2 students of Spanish and Portuguese or Spanish combined with other languages. The module is designed as an introduction to the Iberian Peninsula from three interrelated angles: history, culture and society. The first part of the module related to Portugal introduces students to Portugal and Lusophone Africa, namely the return of the Portuguese from Angola after the Carnation Revolution through Dulce Cardoso’s The Return (O Retorno, 2011). The second part is focused on the last years of the Colonial War in Angola by reading Pepetela’s Ngunga’s Adventures (As Aventuras de Ngunga, 1972). Students then go on to learn more about the history of Portugal, namely the overseas discoveries, slavery, the dictatorship, and the shift to democracy.

— Dr Conceição Pereira, module lecturer.

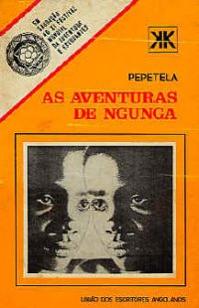

The historical fiction novel As Aventuras de Ngunga (Ngunga’s Adventures), by well-known Angolan author Pepetela, was written, re-edited and translated under differing historical and cultural contexts. Here I consider the two Angolan editions of the novel, published in 1973 and 1976, as well as the English translation by Chris Searle, published in 1980, to understand each edition’s significance and interpretations. While each of the three editions carries different meanings and intentions, they all have the aim of educating several generations across the world on the anti-colonial struggle in the former African colonies, particularly in Angola.

Pepetela initially wrote As Aventuras de Ngunga in 1972 whilst fighting as a guerrilla for the MPLA (People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola), one of the main nationalist groups in the Angolan War of Independence. When he first wrote this text, Pepetela’s intentions were clear – the MPLA needed educational texts that could be used in their schools to teach their young pioneers Portuguese in order to communicate with each other. Phillip Rothwell describes Pepetela as a ‘cultural midwife’ to Angola and argues that Pepetela ‘tells the story of the MPLA even more than the story of Angola’ (2019, p. 2). When examining this edition of the novel, it is clear that Pepetela made the MPLA the focus of his writing, building the plot around the importance of education in the struggle for liberation. This can be seen clearly in the novel through the young Ngunga’s own struggle to understand the significance of teaching and learning in the schools. Pepetela wanted to make it clear that although the liberation movement required violence to achieve its aim of freedom, it also needed educated pioneers who could read and write. Education in itself is presented as a victory over colonialism in the novel.

Nevertheless, Pepetela initially had no intention of publishing As Aventuras de Ngunga as a novel. The text was ‘originally distributed, in five hundred typed copies, on the MPLA’s eastern front’ (Hamilton 1993, p. 266) and did not become a story in its own right until Pepetela realised it had many of the elements of a novel. Following this, he developed a storyline and later published the first edition of As Aventuras de Ngunga in 1973. When this first edition was published, it became a work of historical fiction, combining fiction with reality as a way to observe the world, without shying away from its controversies and contradictions. Rather than adopting a Manichean view, where everything is either all-good or all-evil, Pepetela chose to show the signs of corruption and greed within the MPLA and among some Angolans. Whilst the Portuguese colonialists are written as all-evil characters, Pepetela addresses the moral grey area within the Angolan pioneers with characters such as the Cook, an Angolan who worked for the Portuguese International Police (PIDE), and Kafuxi, the corrupt president of a Kimbo (small rural community). Ngunga begins his journey with the view that the MPLA soldiers and Angolans are all good, but as he becomes a man through his education, he realises some are overtaken by greed and selfishness just like the Portuguese colonialists. This demonstrates that Pepetela is not naïve to the corruption that can take place in organisations like the MPLA, but instead chooses to show that the biggest struggle is that against colonialism.

Ngunga learns of the constant battles in the world around him – not only physical, but moral – and chooses to change the world. By showing the moral struggle faced by Ngunga regarding some of the Angolan characters in the novel, Pepetela ‘is able to humanize his people more fully’ (Phillips 2001, p. 142) and make them complex – and therefore more realistic – characters in Ngunga’s story. The novel carries a clear message that overcoming colonialism will only be possible through struggle, unity and education. This is Pepetela’s main intention with the 1973 Angolan edition of the novel: to inspire the pioneers and Angolan soldiers to educate themselves, mature to make their own decisions, and become their own heroes in the face of colonialism and moral struggles.

Following the end of the liberation war in 1974 and the independence of Angola in 1975, the meaning and intention of As Aventuras de Ngunga changed. According to Russell Hamilton, ‘with the arrival of independence, Ngunga became a national symbol’ (1993, p. 266), no longer just representing MPLA soldiers and pioneers, but now becoming a symbol of Angola, of liberation, and of the fight against colonialism. Ngunga was first the hero to which the soldiers compared themselves during the struggle for liberation and, with the 1976 edition of the novel, he became the hero against which all Angolans judged themselves. For, as Iain Thomson writes, a hero functions like a mirror, ‘reflecting back to the group an idealized image of itself’ (2011, p. 100).

In 1976, Pepetela himself was made Deputy Minister for Education of Angola, further giving his work a new purpose. It is true that As Aventuras de Ngunga always had the purpose of educating, but now it served to educate a whole nation, a way to unite Angolans following liberation, reminding them of the qualities of a true Angolan such as Ngunga. With Pepetela’s enlarged influence over education in Angola, along with the strong anti-colonial sentiment that could be felt there after liberation, it is no surprise that As Aventuras de Ngunga evolved to have a new meaning in the country. During the colonial period, the education system in Angola revolved around Portuguese history and Portuguese geography, but following liberation, those with a higher level of education played a fundamental role in creating a new national consciousness, centred around Angolan national identity. The importance of Angolan literature in this cause is shown by Márcio Mucedula Aguiar, who emphasises how novels such as As Aventuras de Ngunga can be used in the fight to overcome a racist and Eurocentric viewpoint, characteristic of postcolonial societies arising from Portuguese domination (2011, p. 14). Pepetela uses this edition of his novel to recreate the ideals and identity of independent Angola, now free from its colonial chains, yet still struggling from the consequences of long-term Portuguese colonialism and racism.

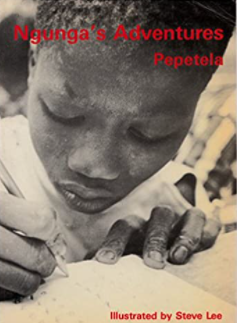

With the English edition of Ngunga’s Adventures, translated by Chris Searle and published by Young World Books in 1980, the interpretations and intentions of the text have further been changed. Whilst the Angolan editions carried the purpose of educating first the young pioneers and then the whole of Angola about the importance of education in the anti-colonial struggle, the English translation has the wider aim of educating young people in the Western world (more specifically, Great Britain) about the issue of colonialism and the process of decolonisation. This can be seen through Searle’s translator’s preface, where he writes that ‘Ngunga still lives in Africa, anywhere where the African people are … fighting the vestiges of colonialism and racism’ (Pepetela 1980, p. 3). Searle widens the scope of Ngunga’s story to make it clear that colonialism is far from over and is most definitely not limited to Angola.

The English translation of Ngunga’s Adventures played a part in filling the void in the British educational system when it came to challenging Eurocentricity in schools. Young World Books, a registered charity created with the purpose of developing anti-racist materials for young people, intended to make the ‘anti-imperial attitude’ (Pepetela 1980, p. 62) accessible to British children through translations like Ngunga’s Adventures – something that was severely lacking in Britain at this time. In the broader historical context, it could be argued that the 1970s were a period of blossoming educational reform in Britain, with several debates taking place surrounding improving inclusivity and accessibility to a well-rounded education. However, following the Second World War, Britain had become increasingly suspicious of ‘foreigners’, with many Britons strongly opposed to sharing the recent social advances with those who were not born in Britain, more specifically with those who, some argued, didn’t belong there. This change in attitude, along with a dramatic increase in immigration and increasing ethnic and religious diversity, meant that the issues of race and racism became frequent topics of discussion in the decades following 1945.

In response to these important developments, many forward-thinking teachers and figureheads of 1970s Britain, one of which being Chris Searle himself, pushed for a shift in the educational syllabus. Before becoming a teacher, Searle was well-known for his anti-racist attitude and activism that he developed after his travels around America and the Caribbean, where his outlook on life was changed through events such as the murder of Martin Luther King, the anti-Vietnam protests, and the Black Panther movement. It was not only Searle’s beliefs, but also his efforts to educate the younger British generations of the time on anti-racism and anti-colonialism, that made him the ideal translator for Pepetela’s novel. Through this translation of Ngunga’s Adventures, Searle allows Pepetela to reach a broader audience and makes readers reflect on colonial and post-revolutionary society and the world (see Castro 2015, p. 209).

In short, the story of the young pioneer Ngunga and his adventures was originally intended to teach young Angolans about the significance of education and moral strength in the fight against colonialism. It was written to give them a common goal, portraying someone who fought the same struggles as them and that they could aspire to be. After Angolan independence, the novel also took on the purpose of unifying a newly liberated nation and reinventing its national identity. The 1980 English translation of Ngunga’s Adventures carries a different intention than that of the Angolan editions that came before it, insofar as its new audience is one that was unfamiliar with the struggle against colonialism, especially that which took place in Africa and specifically Angola, due to the lack of anti-racist and anti-colonial literature available in the British education system. Yet, it still shares the most important aim that applied to all three editions of the novel – that of education.

References

Aguiar, Márcio Mucedula. (2011) O uso da literatura infanto-juvenil de pepetela para consciência e superação do colonialismo e racismo. Revista Espaço Acadêmico 11 (126), pp. 13–20.

Castro, Fernanda. (2014) Entrevista a Pepetela. Navegações 7 (2), pp. 29–213.

Hamilton, Russell. (1993) Portuguese-language literature. In: Oyekan Owomoyela, ed. A History of Twentieth Century African Literatures. University of Nebraska Press, pp. 240–284.

Pepetela. (1976) As Aventuras de Ngunga. Luanda: União dos Escritores Angolanos.

Pepetela. (1980) Ngunga’s Adventures: A Story of Angola. Translated by Chris Searle. London: Young World Books.

Phillips, Richard. (2001) Politics of reading: Decolonizing children’s geographies. Cultural Geographies 8 (2), pp. 125–150.

Rothwell, Phillip. (2019) Pepetela and the MPLA: The Ethical Evolution of a Revolutionary Writer, Cambridge: Legenda.

Thomson, Iain. (2011) Deconstructing the hero. In: Iain Thomson. Heidegger, Art, and Postmodernity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 141–168.

[Charlotte Pickles is currently a second-year student studying Spanish, German, and Portuguese at the School of Modern Languages, Newcastle University. This is her first ever blog post, and she is delighted to be sharing her thoughts on a topic that carries such cultural significance in the context of decolonisation.]