In the forthcoming years, National Health Systems of developed countries will have to cope with several challenges. For example, providing high quality services to an ageing population living longer with more chronic diseases amidst fiscal constraints. On account of this, a team led by Sir Bruce Keogh has released various reviews containing proposals for tackling this impending predicament in delivering urgent and emergency services. One controversial proposal is based on an organisation redesign strategy of certain health services (e.g. acute care centres) in order to get a more centralised structure.

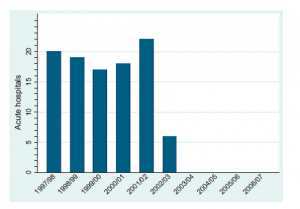

Before the creation of Academic Health Science Centres in 2005, the period between 1997 and 2005 saw England experience 112 consolidations (e.g. mergers and acquisitions) from the existing 223 acute hospitals (Gaynor et al. 2012) (the graph below shows the distribution of mergers and acquisitions).

Source: Gaynor et al. (2012)

Given these figures on mergers and acquisitions, what are the drivers that lead to the centralisation of services? Various explanations have been presented that enhance the promotion of a more centralised structure of health services. Some argue that centralised services are associated with better health outcomes. Morris et al (2014), for instance, have recently examined the effects of centralisation of acute stroke services for patients in metropolitan areas of Manchester and London. Using a difference-in-differences regression analysis approach on individual patient quarterly data, the authors concluded that a centralised provision of hyper acute care may be associated with reductions in both the mortality rate and length of hospital stay.

Another common argument behind the reconfiguration of services is based on the potential improvements derived from the new health market structure that results from a consolidation. More concentrated centres may perform more efficiently since they gather a higher number of staff devoted to various activities and therefore the costs associated with the management of complex patients might be reduced. Fulop et al. (2002) studied whether various mergers (e.g. acute care, mental health and community care services) that occurred in different Trusts based in London effectively reduced management costs. They found that insufficient control of how activities were performed within the centres, and especially the different management structures between the centres, had notably restricted the effect of mergers for reducing management costs. Using the same rationale, centres that centralise resources may perform better due to the increase in the economies of scale and scope. This may be translated into gains in terms of quality. Considering this point, Gaynor, Laudicella and Propper (2012) explored the wave of hospital mergers that occurred in England from 1997 to 2006. The aim of that paper was to estimate the effect of mergers on several performance indicators. After analysing productivity, waiting times, clinical quality and financial performance they did not find significant gains linked to consolidation strategies. However, the authors warn about the potential losses that may appear in patient welfare derived from a consolidation strategy. By reducing the number of potential suppliers, the range of choices available for the patient are also reduced and therefore there may be restrictions in the quality of the services.

So, does competition increase the quality of care? This is difficult to say since quality and competition are endogenous in healthcare markets. However, if some conditions within the market are met, such as fixed prices which are established according to patient diagnoses, then it is possible to see improvements in quality. Gaynor, Moreno-Sierra and Propper (2010) exploit a reform in English NHS consisting of patient choice to analyse its effects in terms of quality. They also used a difference-in-differences approach to find that those areas where centres were more concentrated registered poorer clinical quality measured by the risk-adjusted mortality rate after hospital admissions.

Promoting competition between centres without considering prices has led centres to having stronger incentives for guaranteeing a solid financial performance while maintaining a good level of clinical achievements. In addition, this strategy has not implied significant changes in the patterns of medical use according to the socio-economic status of patients. Similar analyses which have been applied in other frameworks such as private markets of General Practitioners suggest that higher concentration may support higher prices. Given the importance of the health sector not only economically but also in terms of the well-being of the population (Gaynor, Ho and Town 2014), designing alternative schemes for the organisation of care combined with an expert knowledge of the local healthcare market is needed. Despite the relatively little attention received, policy makers should consider the underlying implications and economic theory behind the functioning of health care markets. Evidence on those may help to suitably address the hurdles of the future.