Following the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) public board meeting on the 17th September, the existing proposals for value based assessment (VBA) have been dropped. The proposals suggested ways in which the current health technology appraisal (HTA) process could be adjusted in order to take into account “burden of illness” (BOI) and “wider societal benefits” (WSBs), but little agreement was found amongst those that responded to the consultation. The proposals had involved characterising BOI and WSBs using proportional shortfall and absolute shortfall, respectively.

What is Proportional Shortfall?

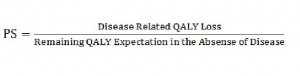

Proportional shortfall, originally introduced by Stolk et al (2004), is a proportional equity concept that has been put forward as a possible way to weight QALYs, or as a way to provide additional information about the severity of a condition for consideration by policymakers.

It is calculated by taking the disease-related QALY loss and dividing it by the remaining QALY expectation in absence of the disease. As a simplistic example, take a serious disease that typically results in a reduction in remaining expected lifetime QALYs from 80 to 40. In this case the proportional shortfall is 0.5 (40/80). Values of proportional shortfall that approach 1 indicate that the illness is particularly life-threatening; hence giving more weight to illnesses with a larger proportional shortfall is broadly consistent with the existing end-of-life (EOL) treatments protocol.

Advantages of Proportional Shortfall

Proportional shortfall seems to sensibly characterise BOI, and as it is based on QALYs both quality and length of life are taken into consideration. In addition to this proportional shortfall is not strongly influenced by age, unlike absolute shortfall. Using the previous example, which has the characteristics of a disease that affects young people, the absolute shortfall would be 40 QALYs (80-40). However if you take another disease that instead affects an elderly population, there will be significant differences. For example, imagine a disease that reduces remaining expected lifetime QALYs from 8 to 4; the absolute shortfall would be 4 QALYs (8-4). The absolute shortfall is 90% lower in the latter case, whereas the proportional shortfall would be identical at 0.5. In the UK where age discrimination is against the law it would seem inappropriate to use absolute shortfall, or other approaches that are influenced by age, to characterise BOI. In fact it would probably be wise to avoid any such age-based approaches under the WSBs criterion too, given the likely negative public reaction.

Another advantage of proportional shortfall is that it is easy to implement. The only additional information that would be required for proportional shortfall to be calculated within an economic evaluation would be average health state utility values for the general population across different ages and genders. These have already been calculated in the UK.

Disadvantages of Proportional Shortfall

While there are several clear benefits to proportional shortfall, some criticisms were made by those responding to the VBA consultation. As the calculation requires the average age at which the illness is diagnosed, it may disadvantage conditions that typically have delayed diagnoses if this isn’t taken into account. Furthermore using it in isolation would potentially lead to a system that is heavily biased in favour of terminal illnesses. Another point raised was that its use, inevitably, discriminates against younger people as they may face a large QALY loss only to be told that this is valued the same as a much smaller QALY loss (as in the earlier example). This is a fair argument however the notion that all QALYs should be valued equally has been disputed in the literature for a number of years (Dolan et al, 2005). Ultimately the weighting of QALYs should be based upon public opinion.

Evidence of Support for Proportional Shortfall

Stolk et al (2005) found “moderate to strong” support for proportional shortfall in the Netherlands, although they only used a small convenience sample. Regardless, according to van de Wetering et al (2013) there is a broad consensus in the Netherlands that it will be used for equity weighting and efforts are being made to find the best way to operationalise it. In Norway, a general population study found little support for proportional shortfall, with far more support for a “fair innings”-style approach (Olsen, 2013). In the UK the EEPRU VBA Survey looked at preferences towards a number of VBA criteria. Their main focus for the BOI criterion was absolute shortfall, however they were able to look at preferences towards proportional shortfall and found little evidence of support for this approach.

The lack of research into public support for proportional shortfall in the UK and elsewhere may partly explain the split in opinions of those that responded to the VBA consultation. 33% responded that proportional shortfall appropriately reflected BOI whereas 28% felt that it did not (the other 39% responded that it partially does).

What now?

As it stands no changes to the existing HTA process will be made in the short term. NICE have suggested that further consideration should be taken with regards to the incorporation of BOI and WSBs into the HTA process. What is clear is that very little research has been undertaken to examine public preferences for the various different equity concepts that could be incorporated into economic evaluations, and more would be helpful. While it would be easy to disregard proportional shortfall at this stage, its practicality should not be understated. There may still be a role for proportional shortfall to play in the near future.