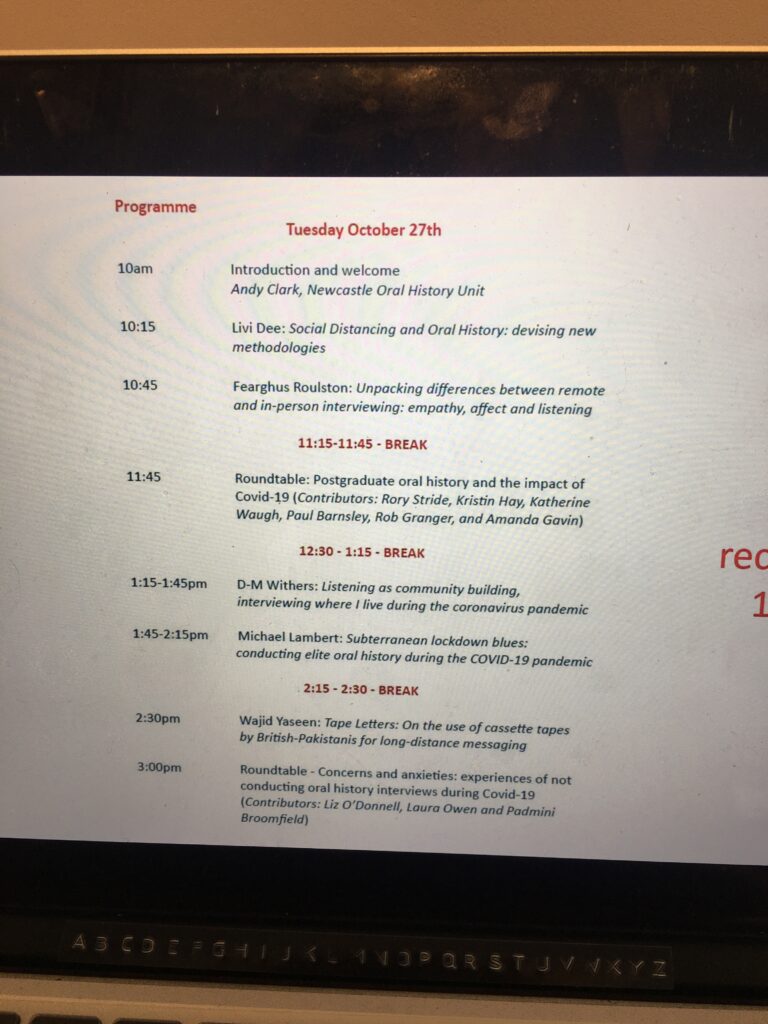

I zoomed into a “workshop” with PGR and professional archiving people. I say “workshop” with speech marks because people are becoming very liberal with this word. Workshops produce outcomes and involve interactions, presentations and panels do not do this. Stop using this word. Anyway it was very interesting and helpful because I could actually talk to people using archives and archivist. So with further ado lets get reviewing…

One of the big issues currently is that people cannot get into archives, this happens at different levels. Some researchers have access to digital archives, but then they can’t read the photos, some only have access to the catalogue and some have zero access. This is due to the fact that all archives work in different ways and many are at different levels of digitisation. This can be due to money but also different laws and regulations of the country the archive is situated in. This limited or complete lack of access is very annoying if you are doing a PhD that only has a certain amount of funding. Over the various Zooms I have part taken in I see that it causes a lot of frustration but I have also observed that people are getting more creative in the ways they get hold of documents. For example one person mentioned that eBay is a great source of archival images. Another person mentioned that they had started to use their network to gain access to artefacts. They were doing a project that involved using German archives, which turns out are not good when it comes to digitising, so they got people they know to send them photographs. This was not the first someone had told me about this. It seems that in some cases it is better to rely on humans to find stuff in the archives than computers. Which brings me to my point:

STOP REPLACING PEOPLE WITH ROBOTS

I asked a question to the PGR panel about what they thought about digital archives verses the physical archive (aka Brick and Mortar Archives). They gave some great answers around missing the materiality of documents, how you lose the serendipity of archiving in digital archives and how online catalogues do help setting up before going into a brick and mortar archive. They also mentioned the common problem of tags and keyword searches not being good enough. One of the archivists that works in the University of Nottingham archives responded to this by saying that people should always ask the archivists what they are looking because they know the archive. This in combination with the people using their networks in order to access archives got me thinking that our drive to digitisation in archives is having the same effect as it is having in different places. It is replacing people with computers that definitely cannot do the job in the same way. For example I have a dislike for the self check outs because it clearly does not work as well as a human cashier, which is evident by the staff member who has to stand next to the machine.

Do not get me wrong I am not against digitisation nor do I believe that archivists’ current job outline does not need updating. But I believe that relying heavily on digitisation will not solve our archive problem nor will employing more of the same archivists. We need something in between. Something that has the similar flavour to people using their international network to send archives across borders, which would not be possible without both technology and humans.

OK second note…

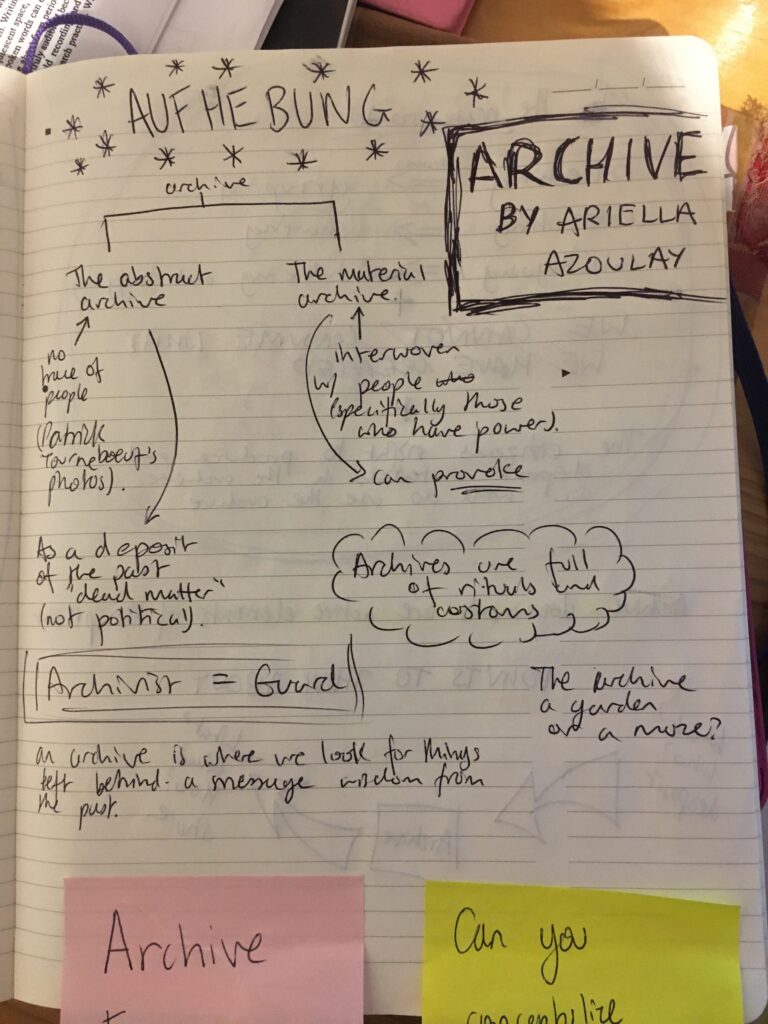

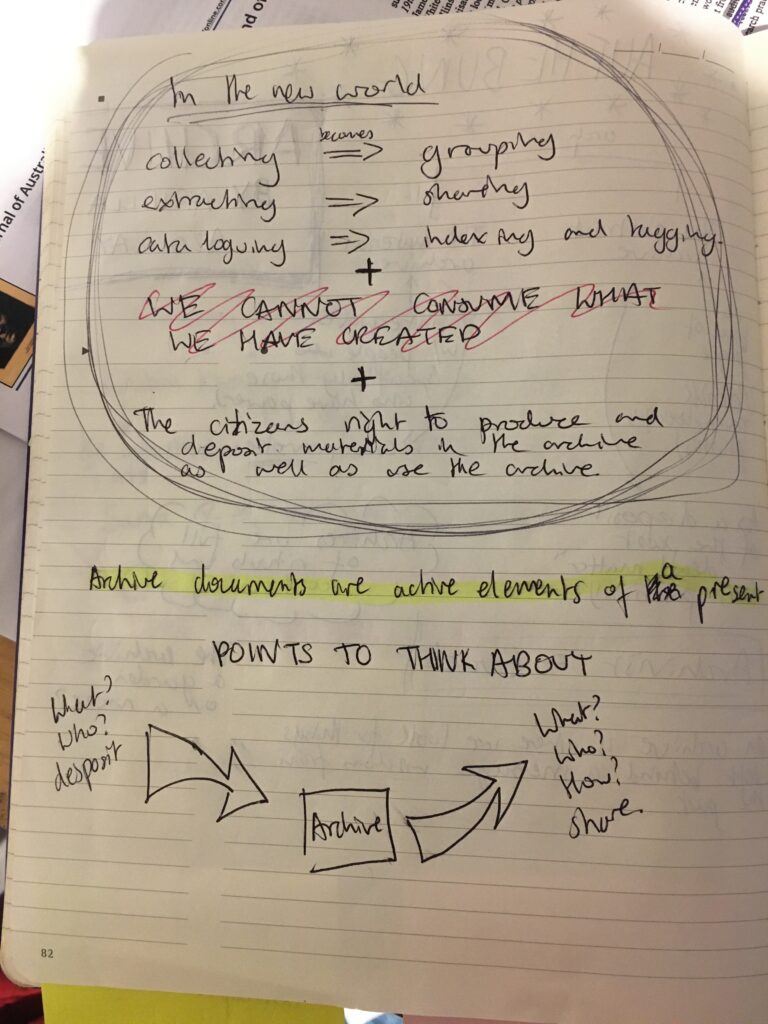

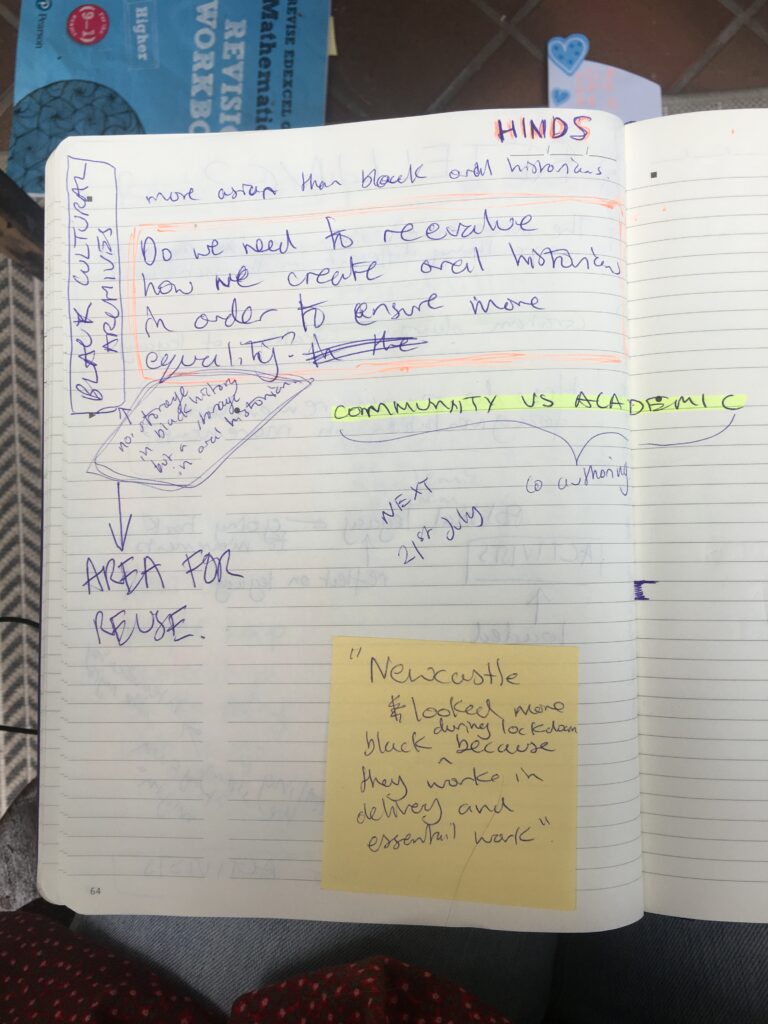

As I am currently exploring a lot right now the existence of an archive also creates the ‘existence’ of histories lost. What was interesting about this panel is that the majority were doing work with minority histories BAME and LGBTQ+ etc. Because of this many of them talked extensively about how they managed and handled the gaps that are found in archives that represent the neglected histories. One person talked about counter-reading which is the method on examining the gaps in an archive, the reasons these gaps might exist and then combining this with the contextual knowledge in order to create a history.

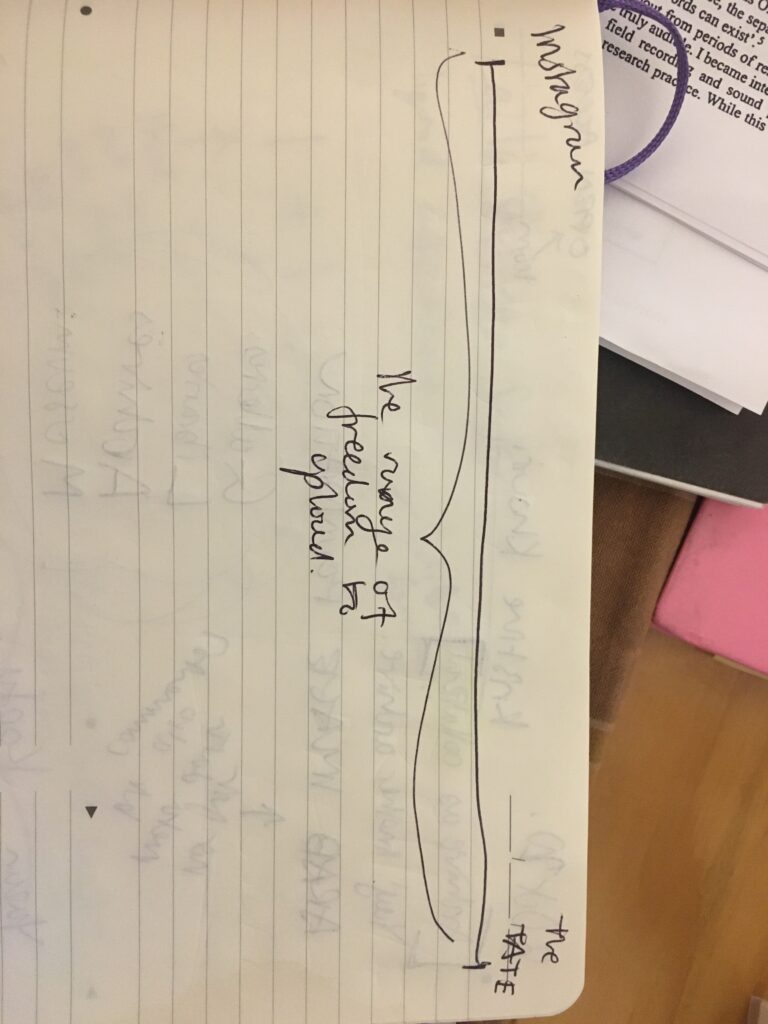

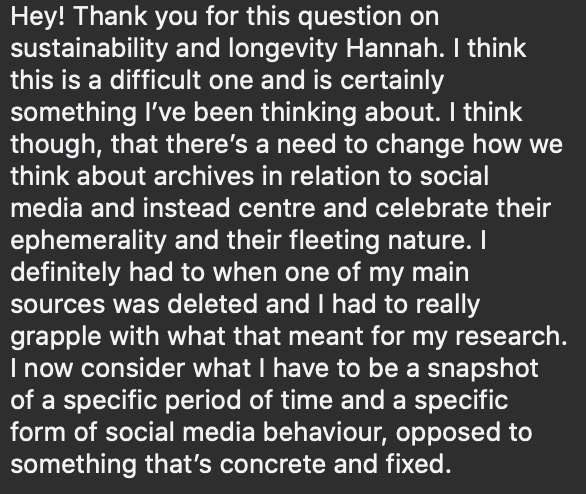

One of the speakers was using social media as an alternative archive and I asked her how she felt about the ethics of having an archive on a social media:

We continued the conversation and started to talk about the principle of counter archives; archives that are created by those not represented in brick and mortar archives, often using a more DIY attitude. By DIY attitude I mean only using the resources you have access to, so in many contemporary cases this means they do end up only.

I believe that further investigation into these counter archives and methods like counter reading could hold some interesting ideas on how we might approach the SDH archive.