With Kristine Khouri (Arab Image Foundation), Yazan Kopty (Imagining the Holy), Sana Yazigi (Creative Memory of the Syrian Revolution) & Discussant Laila Shereen Sakr (UCSB). 08/10/20

This talk was recommend to me by Joe because he is on the mailing list for talks at NYU. He joined me for the zoom (obviously it had to be a zoom).

The talk was interesting and generally it was nice to attend a talk again even though it was in my living room. Many different topics were discussed but there was less discussion around digital archives and the consequences of digitising. This was a little disappointing although not surprising, because as you often get with talks the speakers will always bring the conversation to their research. And who can blame them, we all suffer from ‘the researcher’s lens’ where you view the world completely through what you are thinking about. However, during this talk it meant less talking about the digital and more talking about post colonialism and decolonising archives, which is still very interesting. And not surprising as the talk was organised by middle eastern studies at NYU.

Anyway what follows is some of the things I picked up on during the talk.

Archive as collateral

Something that was briefly brought up in the talk was the idea of a collateral archive. In other words, an archive that exist because at the end of a project you realised that you had enough stuff to make an archive. If you take this term in its broadest sense everyone has a collateral archive: diaries, planners, notes, shopping lists etc. All of these can make up an archive of your life. The same can be said for any project. If we take the Hand Of school summer project, NTSW then you could very easily create an archive from the kids sketchbooks to the notes of the planning meetings. Every thing can be archived.

But there are some questions to be asked, one: should it archive in the first place, and two, if so how should it be archived? Now the first question is a big one and one I will probably revisit several times. The second question was triggered because in the talk one of the speakers had set up a completely new archive because they looked at all the stuff they had collected for their project and decided that they might as well make a archive, hence collateral archive. So should they have made a completely new archive? Or should they have added to an existing one? Or should have created it but then have it live in a network of other collateral archives?

Another big question is whether people should think about their collateral archive before they start a project or after? Should there be a software that allows for easy archiving as a project progresses? I guess it is often the case that you don’t know what you are going to collect until it has been collected. But then again the internet has led to an increase in document production, so maybe we need to start preparing more for an influx of stuff in order to avoid a desktop soup of documents.

The ‘home’ of History

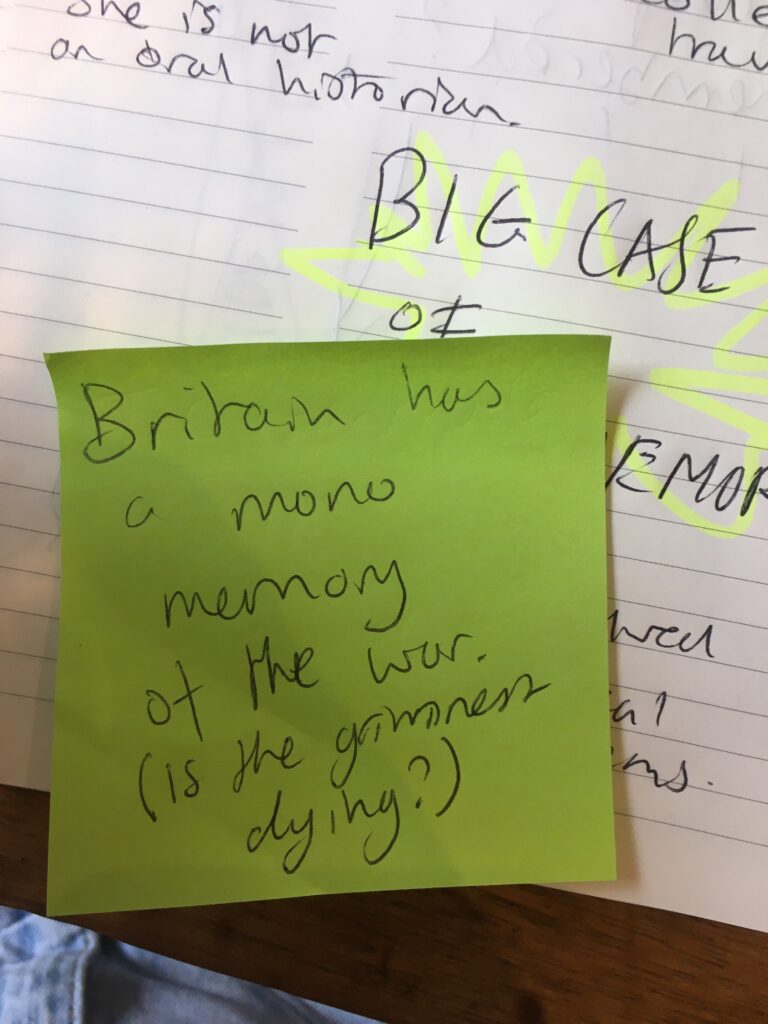

As I previously said the talk was arranged by the school of middle eastern studies, hence the steering of the conversation towards decolonisation. Unsurprisingly the topic of where documents should be stored came up. This was mostly concerning Yazan Kopfy work on Palestine. He is working on gaining more information on photos of Palestine that are stored in the national geographic archive (one hell of a collateral archive by the way, as they were not initially stored there for archiving proposes but as leftover stuff from articles. Which they were thinking of throwing away somewhere in the 1980s as a clearing out exercise.) Many of these photos only state who took the photo and not who is in the picture or any wider cultural information. So he has started to flesh out this information. What was interesting was his comment that people outside of Palestine view it as the holy land when in Palestine it is first and foremost viewed as home. So where do you store photographs taken through the (literal) lens of a coloniser? And how does this work in the digital context? Because even if there is a digital copy there is also a physical copy somewhere.

EXTRA NOTE: this is also where Joe mentioned ‘Nice White Parents’ and how this might be another case where diversity and decolonising is in fact benefiting the white-western academic world more than the people of Palestine.

The Scale of the Digital

There were three main speakers Kristine Khouri, Yazan Kopfy and Sana Yazigi. All three had a very different approach to digital archiving.

On side of the scale I am going to put Khouri, whose project was ‘Past Disquiet’, which she described to be like a website in an exhibition space. She seemed to be slightly fearful of algorithms and digital space. On the other end of the scale Kopfy, who used instagram to collect information on his pictures. Interestingly he struggled to get information on images from the 1920s and 30s, but got lots on photos from the 1970s. I feel this really shows the age of instagram users. And in the middle of the scale I will place Yazigi, who created the Creative Memory of the Syrian Revolution, a rather epic website, which is kept update. The only thing I worry about is the actual user friendliness of it.

To me this wide range of approaches to the digital is typical of our time. There are those who embrace it and those who are fearful of it. Either way there are questions to be asked around big data, data rot and the environment. Because all these digital things are stored on servers which use a lot of energy. Sadly this was not fully disgusted which I do wish they had done.

Hauntings

Nearer to the end of the talk Kristine Khouri started talking about hauntings in the archive. An idea that Joe could get behind if it was art but not necessarily if it was academic. But the idea of ghost and hauntings I do not think is too much of a far fetch idea since going through an archive can be like going through someone’s knicker drawer. I think this is especially true with oral histories because you are listening to the person’s voice. There is a responsibility attached to going through people’s archives. Maybe an increased awareness of people’s presence when researching will deliver a more ethical research or an awareness of their intentions or maybe even warnings about the future.