pop. 001 I am going to start by repeating Susan Leigh Star’s call in ‘The Ethnography of Infrastructure’ to study ‘boring things.’1

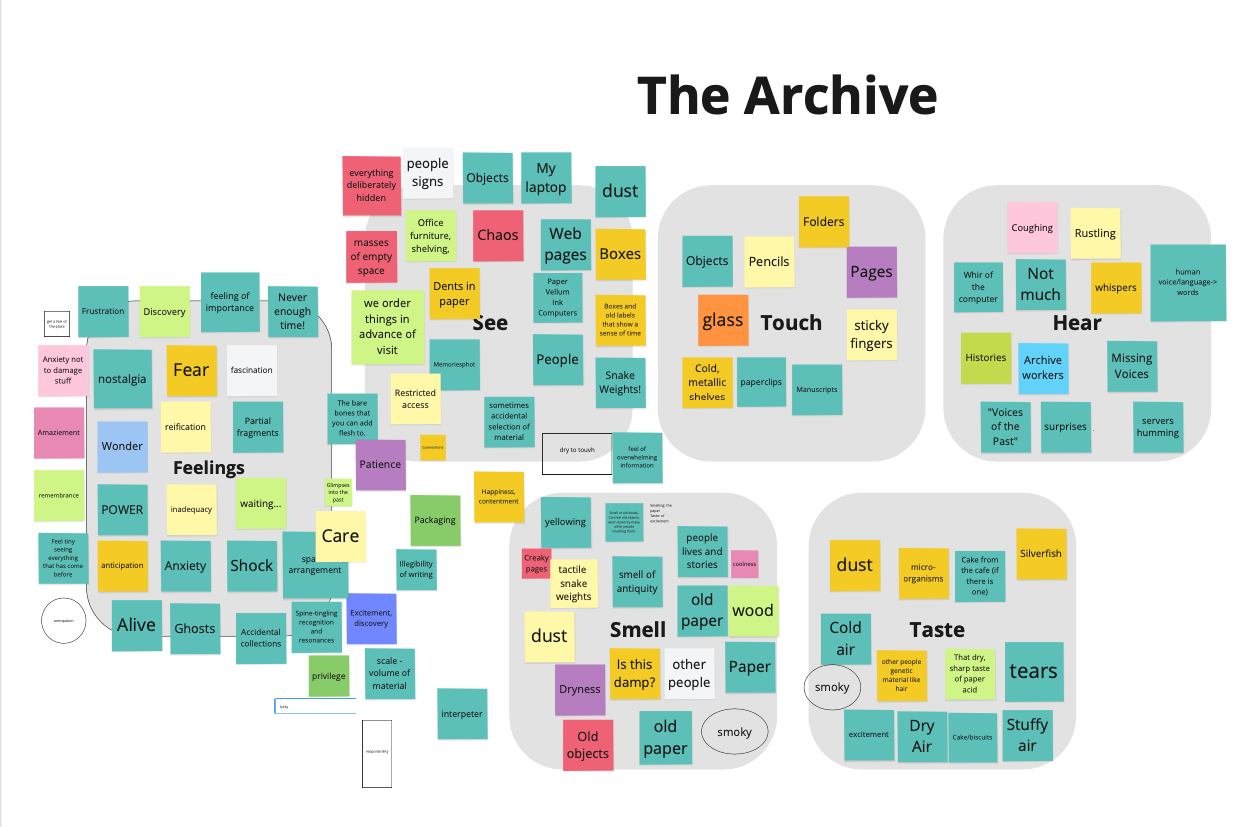

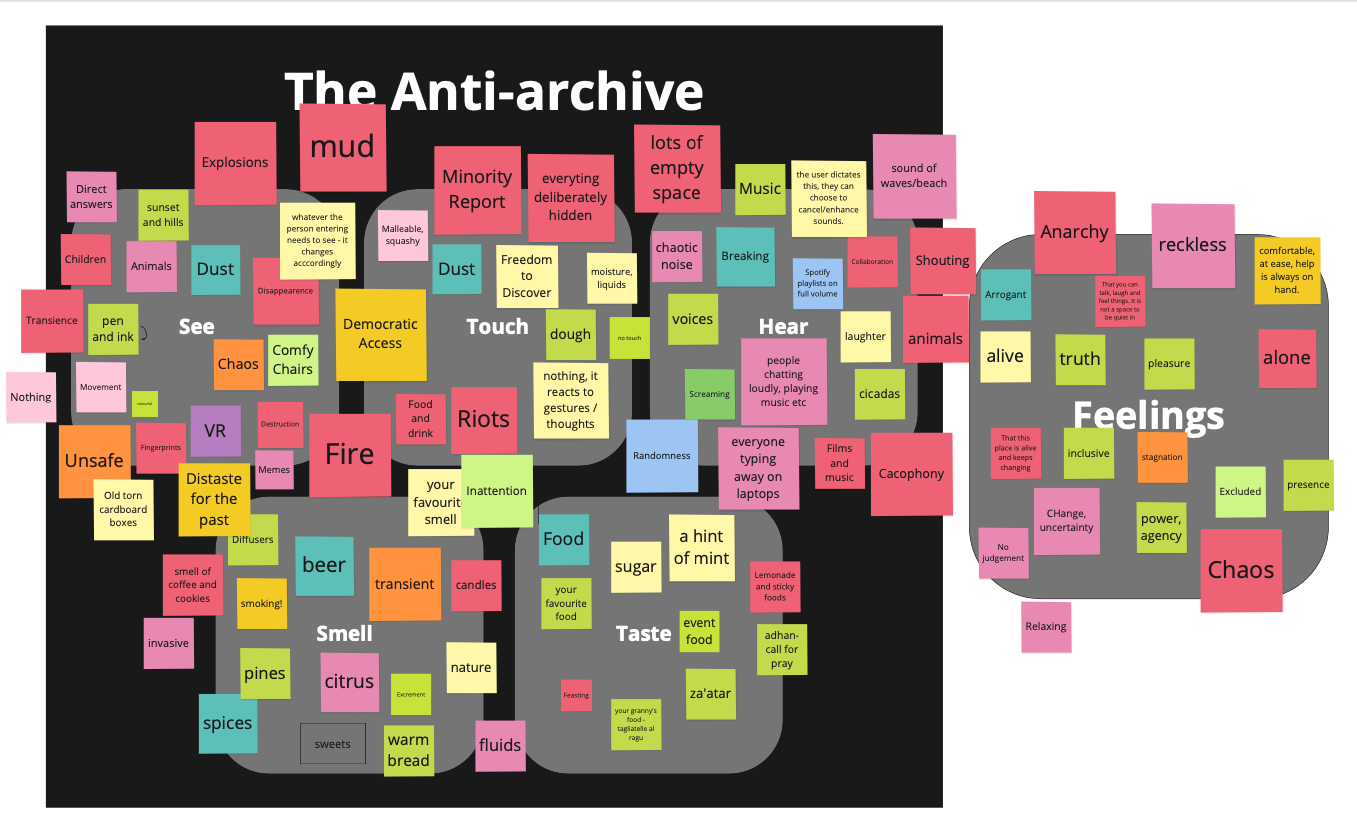

pop. 002 At the start of my research I attended many talks, seminars, and lectures that touched upon this mystical mysterious thing – “the archive.”2 I read Derrida’s Archive Fever and other people’s commentary of the text.3 I drew how it felt to be in an archive and compared the experience to playing open world video games.4 I ran a workshop where the participants first noted all the words they associated with “the archive.” They were then challenged to create an “anti-archive” based on these associations.5

Archives as video games – OHD_RPT_0134

Break the Archive workshop – OHD_WKS_0131

pop. 003 I explored the dimensions, symbols, and feelings of “the archive,” because the topic of my study was the reuse of archived oral history. Oral history is, as Lynn Abrams writes, ‘a creative, interactive methodology that forces us to get to grips with many layers of meaning and interpretation contained within people’s memories.’6 The multiple dimensions and narratives found in oral histories make them a challenge to archive and to navigate, and therefore it has been argued that oral histories are not reused once archived.7 This is not completely true, as there are popular writers who have used archived oral histories as a source for bestselling books on popular historical events, for example the various wars, or particular periods of popular music.8 Nevertheless, navigating and searching oral history recordings remains challenging and time consuming. The initial aim of this project was to seek a solution to this problem of oral history; to design something that would make reusing oral histories easier – something that would embody all the positive feelings I had of the archive.

pop. 004 However, the direction of the project changed when I started to enter the world of archives and was confronted with the reality of preserving oral histories. I talked to multiple archivists, one of whom told me she was currently spending more time managing leaks in the ageing building’s roof than archiving. I also completed three placements which granted me access to the day-to-day of a heritage site and two archives. The heritage site was Seaton Delaval Hall in Northumberland, England. The Hall belongs to the National Trust, Europe’s biggest conservation charity, and was also the location for my bigger oral history project.9 I worked in the Archives at National Centre for Biological Science (NCBS) in Bengaluru, India for two months,10 and the British Library for one intensive month.11 Throughout my project and placements I did boring work, but work that was essential, crucial to its respective organisations, and, eventually, became the central focus of this portfolio.

pop. 005 I ended up not studying “the archive,” rather I studied archives, museums, and heritage sites which collect and maintain our history, and above all maintain access to history. I studied the ‘boring things.’ The study of ‘boring things,’ in my case the maintenance of access to oral histories, reveals ‘essential aspects of aesthetics, justice, and change,’ which stem from the structure of an archive or an archive-like organisation; its standards, forms, and filing systems.12 My study of the ‘boring’ structures, which support access to oral histories, took the form of research through design (RtD), one of the deployments of design that Christopher Frayling discussed in his seminal paper ‘Research in Art and Design.’13 I used design methods to investigate the challenges of oral history access and its maintenance, specifically adopting an action research (AR) approach. I created design artefacts to either explore or explain the structures and used them as probes in conversations with people working within these structures, including the staff and volunteers of my placement organisations. These conversations were crucial in revealing the invisible aspects of maintenance.

pop. 006 Maintenance is often invisible for several reasons. Its output is invisible because it keeps a status quo. As Stewart Brand writes in How buildings learn: what happens after they’re built, ‘the only satisfaction they [maintenance people] can get from their work is to do it well. The measure of success in their labours is that the result is invisible, unnoticed. Thanks to them, everything is the same as it ever was.’14 The workers and their systems are invisible because they are removed from public view: wires and pipes are hidden above and underground,15 and every worker works outside of office hours, creating what Star and Strauss refer to as a ‘non-person.’16 As Star explains, maintenance can become invisible even to those performing it, because the tasks do not need to be ‘reinvented each time or assembled for each task,’ resulting in them becoming strangely passive activities which are transparent and ‘naturalised’ as part of the structure, ultimately taken for granted.17

pop. 007 By completing my three placements alongside my bigger oral history project with the Hall I was able to get a closer look at maintenance in these organisations. I became acquainted with those who maintain, enabling me to slowly map out the requirements for maintaining access to oral histories and see what hinders this maintenance. For my placement at Seaton Delaval Hall I designed the entire system for an on-site Research Room,18 but I also would sometimes have to manage the car park or do room guiding because they were short on volunteers. I audited the National Trust’s 1700 items strong sound collection at the British Library, looking for copyright forms and noting their absence or presence in a spreadsheet.19 I learnt as much as I could about copyright and data protection to write a takedown policy as part of my placement with Archives at NCBS.20 I also spent three years collecting oral history testimonies for Seaton Delaval Hall, summarising them and preparing them for archiving, including creating a copyright agreement specifically for this project.21 The work I carried out during these placements, the discussions I had with my colleagues, and my overall experience of recording oral history make up this portfolio of practice.

pop. 008 This portfolio is a product of my thinking. In ‘Wicked Problems in Design Thinking’ Richard Buchanan says ‘designers conceive their subject matter in two ways on two levels: general and particular.’22 These two levels of thinking are present in the portfolio as I consider it a ‘domain of design,’ to borrow a term from Bill Gaver. A domain of design is a space where the designer (myself) presents their general philosophy of a particular situation, issue, or problem, by bringing together their individually created design artefacts for specific contexts, comparing and contrasting them and putting them in relation to existing theories and ideas.23

pop. 009 The overall idea presented in this portfolio, or domain of design, should function as a source of inspiration for others who are grappling with a similar issue of maintaining access to oral histories. In some parts the portfolio is purposefully ambiguous – ‘the artefact or situation sets the scene for meaning-making, but doesn’t prescribe the result.’24 The domain of design is suited to my research as I have framed the maintaining of access to oral histories as a ‘wicked problem.’

pop. 010 A wicked problem is a term formally established in Horst Rittel and Melvin Webber’s 1973 paper ‘Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning’ and refers to modern societal problems that are difficult to define due to their multidimensional and dynamic nature.25 One of the properties of wicked problems is that ‘every wicked problem is essentially unique.’26 This portfolio embraces ambiguity to accommodate the unique formulations of maintaining access to oral histories. The particulars of the individual design artefacts might not be applicable to every situation, but the general idea shown in the portfolio/domain of design might inspire new ways of thinking; pushing the audience to interpret their own situation and engage with it in a deeper and more personal manner.27

pop. 011 I acknowledge this research project and the portfolio it produced is one of many approaches to the question of making oral histories accessible. As Rittel and Webber point out, ‘the information needed to understand the problem depends upon one’s idea for solving it.’28 Dorst and Cross made a similar observation when they studied design students’ approaches to a particular design challenge. They observed a diverse array of interpretations depending on what the students thought the solution might be.29 My ability to describe the situation surrounding the access of oral histories is directed by my belief that the opportunities to improve access to oral histories lie within maintenance. In the framing, it is impossible to perceive ‘all conceivable solutions,’ therefore what I am articulating cannot be considered a ‘definitive formulation.’30 Nevertheless, I do contribute a novel perspective to the conversation surrounding the access and reuse of oral histories by heeding Star’s call to investigate ‘boring things’ and by focussing on the ‘symbolic sewers’ of archives and similar repositories, namely the standards, forms and storage procedures.31

To create some order in the chaos of a design process this portfolio has been divided into three sections: the Practice, the Wicked Problem(s), and the Case Example.

The Practice

pop. 012 My practice generated new knowledge about the challenges and opportunities associated with maintaining access to oral histories. This section unpacks how my focus on maintenance shaped this project into a form of research through design (RtD), using action research (AR) as my main methodology. It demonstrates how the environments and people I was working with influenced my AR and the outputs I eventually developed.

The Wicked Problem(s)

pop. 013 This section illustrates the various dimensions of the wicked problem of maintaining access to oral histories, as observed in my research within the institutions I worked with. This part of the portfolio aims to map the wicked nature of maintaining access to oral histories by viewing it from two perspectives. The first is what needs to be maintained, focussing on the evolution of technology and how this has changed ideas about access and created demands for new structures which also need new forms of maintenance. The second perspective discusses why in many circumstances this maintenance does not occur, including how the status of maintenance, the ability to maintain, and diminishing resources, hinder the capacity to maintain.

The Case Example

pop. 014 The case example presents the wicked problem of maintaining access to oral histories within the context of the National Trust and Seaton Delaval Hall. It includes the outputs I created to support the staff and volunteers of the organisation in improving and maintaining access to their oral histories. However, it is again essential to remember Rittel and Webber’s seventh property of a wicked problem: ‘every wicked problem is essentially unique.’32 The other two sections draw from all three of my placements, my experience recording oral history, and my wider practice and research to offer a more general perspective on access to oral histories and how this should be managed. This section focusses solely on my work with my central case example demonstrating how to identify opportunities to improve the maintenance of access to oral histories and design materials that will support this process. However, the outputs given in this section are examples, not a prescription.

- Susan Leigh Star, ‘The Ethnography of Infrastructure,’ American Behavioral Scientist 43, no.3 (1999): 377. ↩︎

- James Louwerse, H., Feb 2, 2021, Texts, Images and Sounds Seminars Summary. OHD_Archive. OHD_BLG_0075. ↩︎

- Including Carol Steedman, Dust, (Manchester University Press, 2001). ↩︎

- James Louwerse, H., Feb 4, 2021, Archives are adventures. OHD_Archive. OHD_BLG_0086; James Louwerse, H., Oct, 2021, No Man’s Land. OHD_Archive. OHD_RPT_0134; James Louwerse, H., Jul 14, 2021, Archives as video games, HJL’s Scrivener. OHD_NOT_0200. ↩︎

- James Louwerse, H., Jun 14, 2021, Break the Archive. OHD_Archive. OHD_WKS_0131. ↩︎

- Lynn Abrams, Oral History Theory, (Routledge, 2016), 18. ↩︎

- Michael Frisch, ‘Three Dimensions and More: Oral History Beyond the Paradoxes of Method,’’ in Handbook of Emergent Methods, ed. Sharlene Nagy Hesser-Biber and Patricia Leavy (The Guilford Press, 2010), 223. ↩︎

- See the Forgotten Voices of… series. Waterstones search result, accessed Jan 3, 2025. ↩︎

- ‘Seaton Delaval Hall,’ National Trust, n.d., accessed Jan 3, 2025, https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/visit/north-east/seaton-delaval-hall. ↩︎

- ‘Archives at NCBS,’ Archives at NCBS, n.d., accessed Jan 3, 2025, https://archives.ncbs.res.in/. ↩︎

- ‘Sound and Vision Blog,’ British Library Blogs, n.d., accessed Jan 3, 2025, https://blogs.bl.uk/sound-and-vision/. ↩︎

- Star, ‘The Ethnography of Infrastructure,’ 379. ↩︎

- Christopher Frayling, ‘Research in art and design,’ Royal College of Art Research Papers 1, no. 1 (1993/4). ↩︎

- Stewart Brand, How buildings learn: what happens after they’re built, (Penguin, 1995), 130. ↩︎

- The Pompidou Centre is of course an example of the infrastructure not being hidden. Although it is important to note the building was controversial at the time and the architects, Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano, were not expecting they would win the design competition and so ‘worked with complete freedom.’ See William Cook, ‘A very Parisian scandal: The Pompidou Centre at 40,’ BBC Arts, Feb 8, 2017, accessed Jan 22, 2025, https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/articles/kTlZ2DLm4NCVjkdzXnFHlW/a-very-parisian-scandal-the-pompidou-centre-at-40. ↩︎

- Susan Leigh Star, and Anselm Strauss, ‘Layers of silence, arenas of voice: The ecology of visible and invisible work,’ Computer supported cooperative work (CSCW) 8, no. 1 (1999): 15. ↩︎

- Star, ‘The Ethnography of Infrastructure,’ 381. ↩︎

- James Louwerse, H., Sep 8, 2022, Research Room Donation Flowchart. OHD_Archive. OHD_DSN_0158; James Louwerse, H., Oct 31, 2022, Research Room Acquisition Copyright form. OHD_Archive. OHD_FRM_0192; James Louwerse, H., Oct 25, 2022, Research Room Acquisition Proposal. OHD_Archive. OHD_FRM_0193; James Louwerse, H., Nov 1, 2022, Research Room Agreement. OHD_Archive. OHD_FRM_0194; James Louwerse, H., Oct 31, 2022, Research Room Guide. OHD_Archive. OHD_RPT_0195; James Louwerse, H., Oct 28, 2022, Research Room Information Sheet. OHD_Archive. OHD_WRT_0196; James Louwerse, H., Aug 2, 2022, Research Room Index prototype. OHD_Archive. OHD_DSN_0197. ↩︎

- James Louwerse, H., Jun 22, 2023, C1168 Audit 2023. OHD_Archive. OHD_COL_0262. ↩︎

- James Louwerse, H., Jan 12, 2023, NCBS Takedown and alterations policy. OHD_Archive. OHD_RPT_0249. ↩︎

- James Louwerse, H., Nov 21, 2023, Final copyright form. OHD_Archive. OHD_FRM_0290; James Louwerse, H., Sep 14, 2021, Collection of preinterview stuff. OHD_Archive. OHD_COL_0291; James Louwerse, H., Oct 28, 2024, Receipt of deposit. OHD_Archive. OHD_RCP_0293; James Louwerse, H., Aug 7, 2024, Listening session audios. OHD_Archive. OHD_AUD_0295. ↩︎

- Richard Buchanan, ‘Wicked Problems in Design Thinking,’ Design Issues 8, no. 2, (1992): 17. ↩︎

- William Gaver, ‘What should we expect from research through design?’ Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on human factors in computing system, (2012, May): 945. ↩︎

- William Gaver, Jacob Beaver, and Steve Benford, ‘Ambiguity as a resource for design,’ Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on human factors in computing systems (2003, April): 233. ↩︎

- Horst Rittel, and Melvin Webber, ‘Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning,’ Policy Sciences 4, no. 2 (1973): 155-169. ↩︎

- Ibid., 164. ↩︎

- Gaver, Beaver, and Benford, ‘Ambiguity as a resource for design,’ 239. ↩︎

- Rittel, and Webber, ‘Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning,’ 161. ↩︎

- Kees Dorst, and Nigel Cross, ‘Creativity in the design process: co-evolution of problem–solution,’ Design Studies 22, no. 5 (2001): 431. ↩︎

- Rittel, and Webber, ‘Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning,’ 161. ↩︎

- Star, ‘The Ethnography of Infrastructure,’ 379. ↩︎

- Rittel, and Webber, ‘Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning,’ 164. ↩︎