Tag Archives: Archiving

OHD_RPT_0298 NT OH report

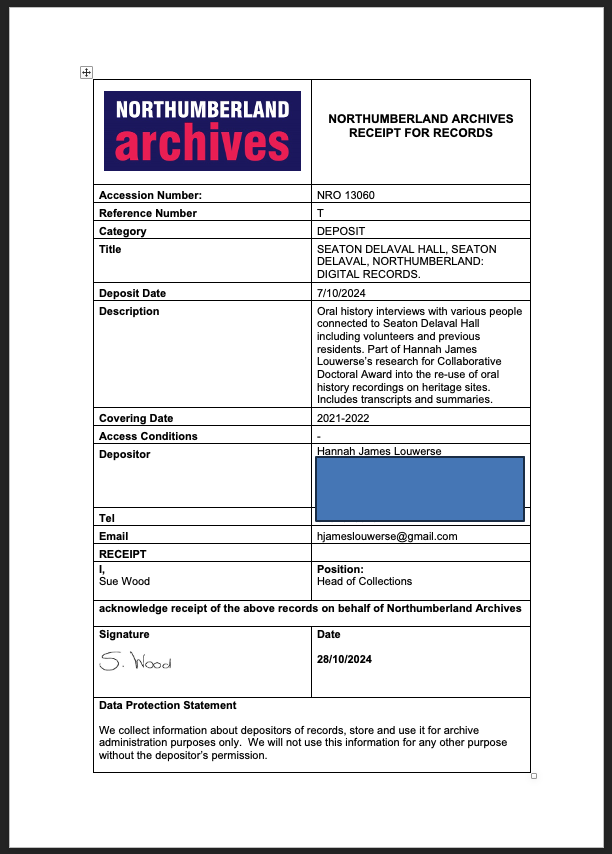

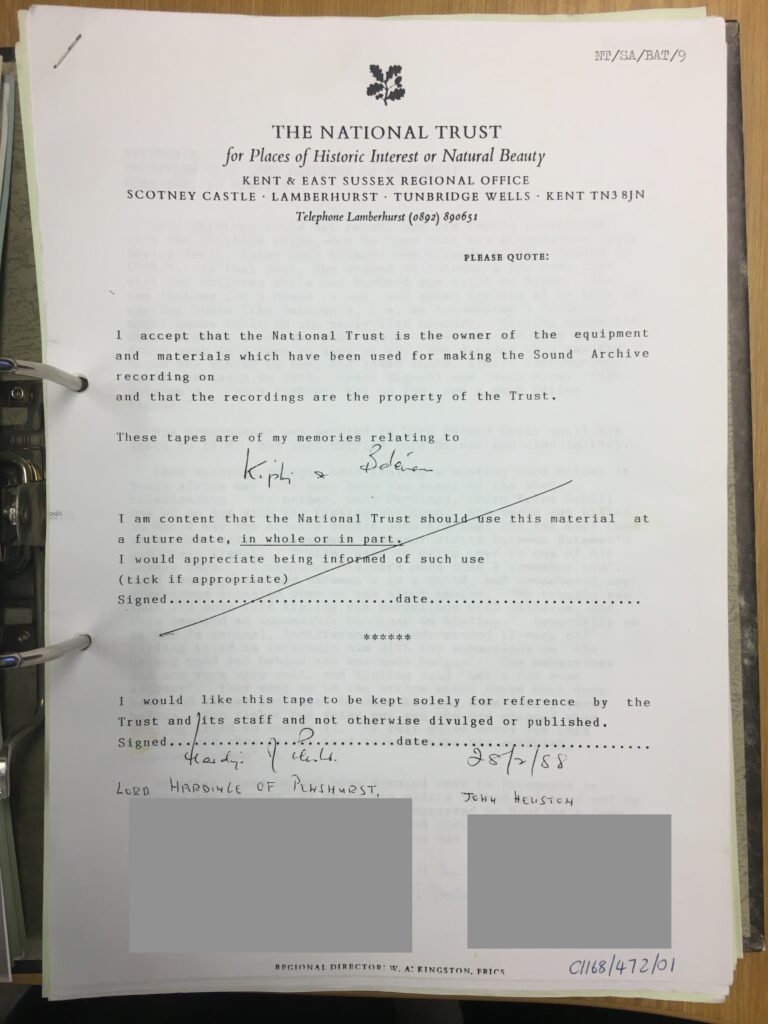

OHD_RCP_0293 Receipt of deposit

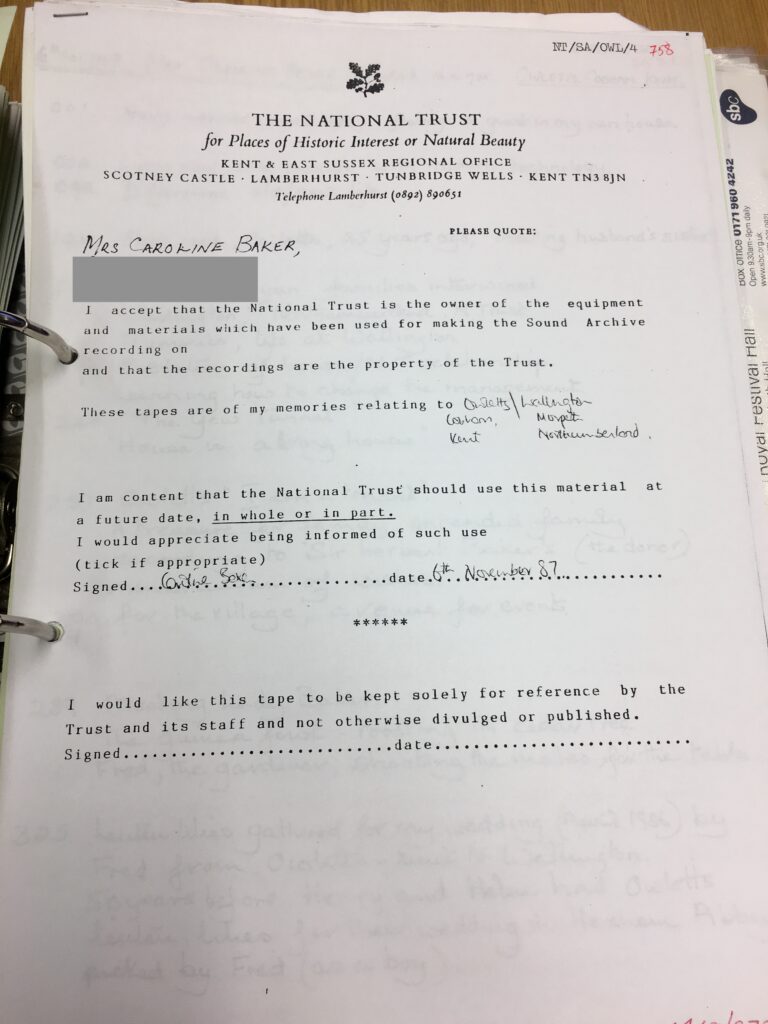

OHD_FRM_0290 Final copyright form

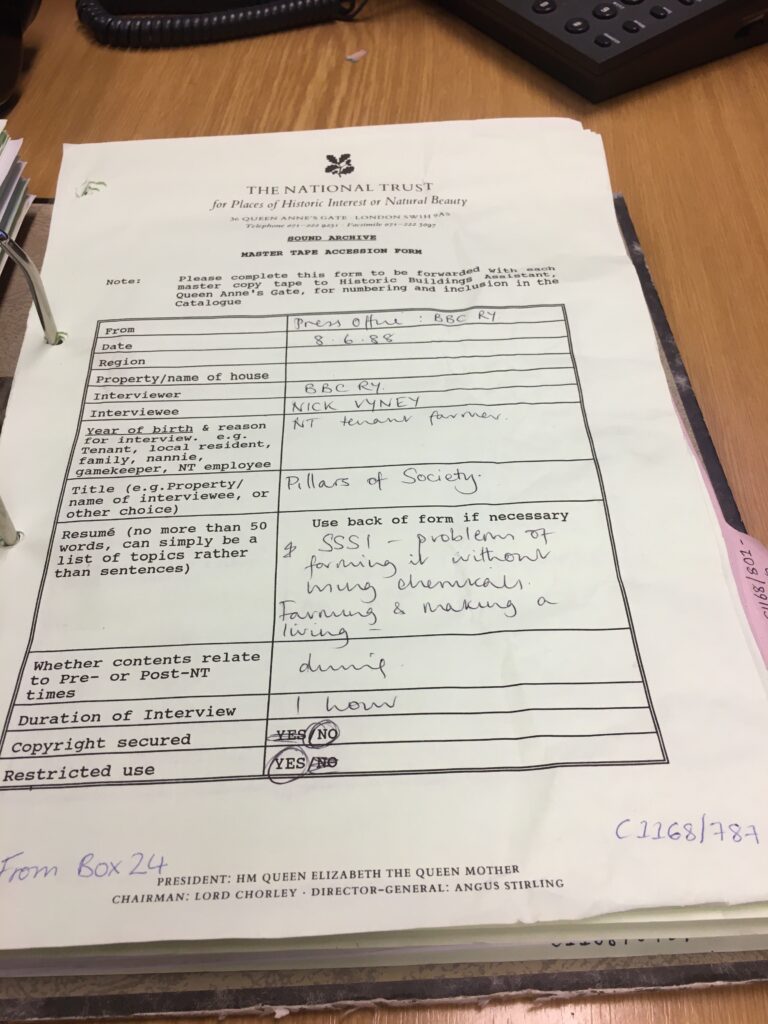

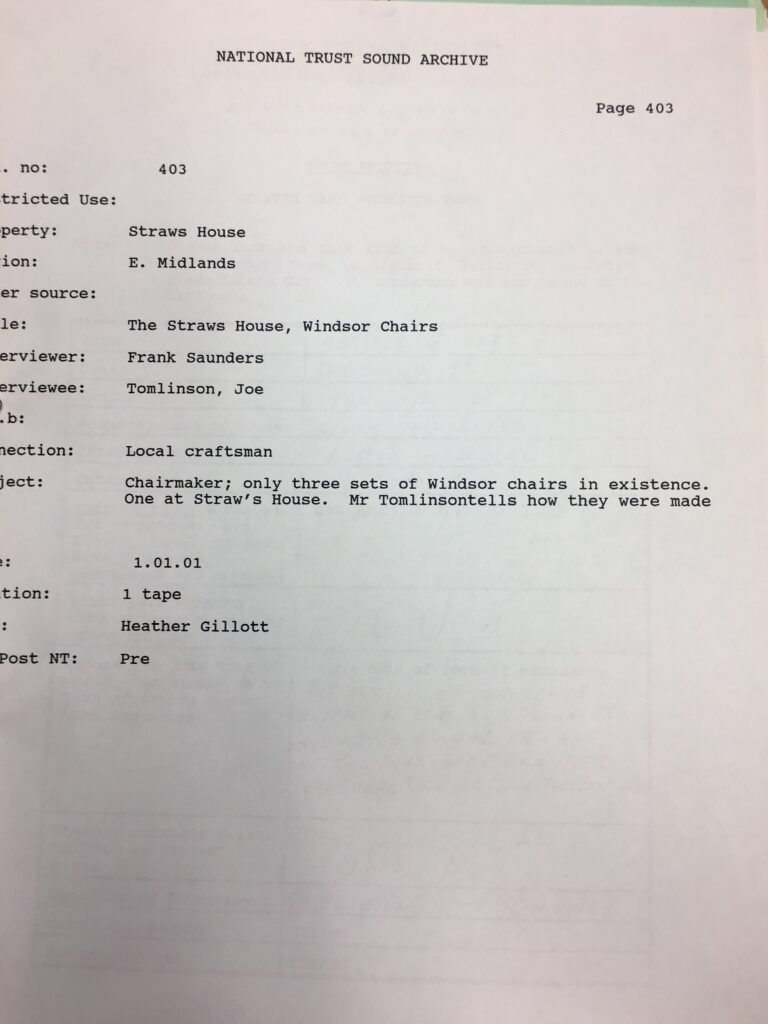

OHD_COL_0272 Collection of photographs of the National Trust Collections’ forms

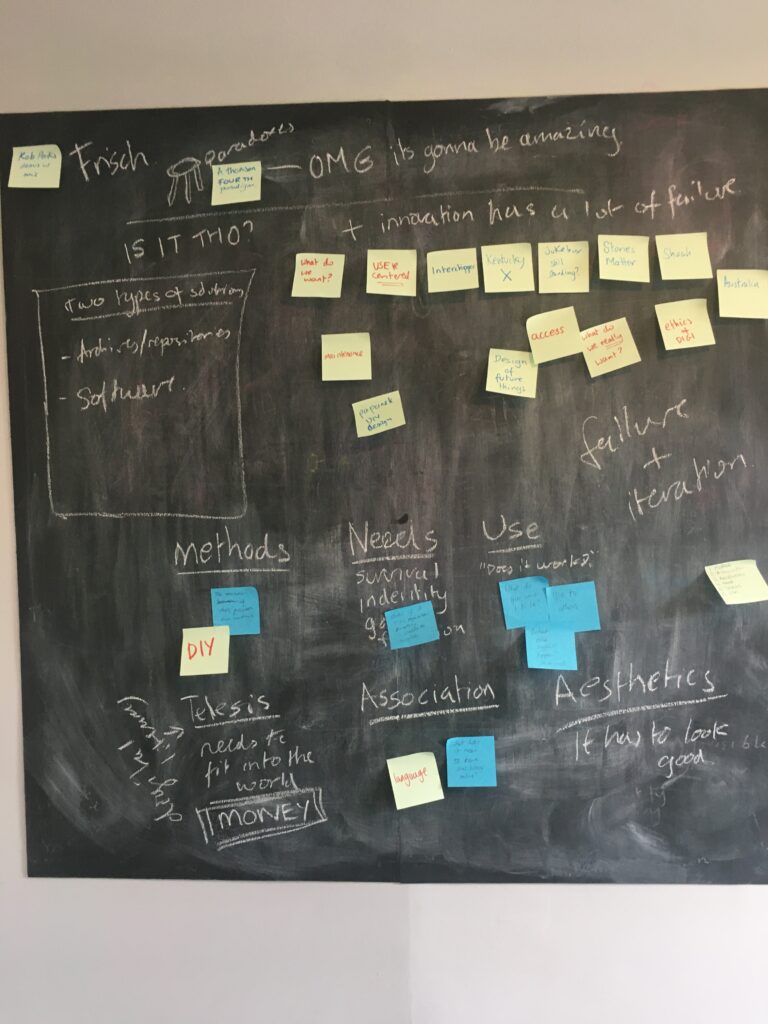

OHD_WHB_0233 Frisch and Papanek

OHD_RPT_0035 Alien in residence

OHD_PRS_0300 Iraq Symposium talk

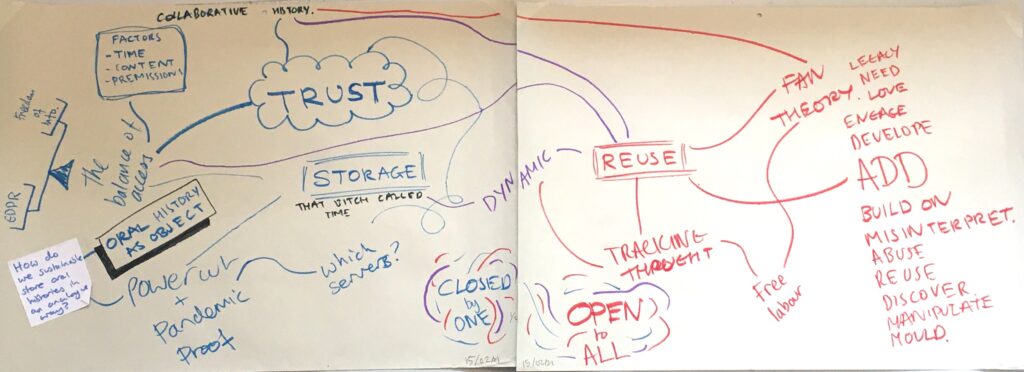

The archiving and reusing of oral history is often dubbed “the deep dark secret” of oral history, because a significant amount of recordings once they have enter long-term storage are not used again. Investigating this issue and trying to come up with solutions has been central to my PhD research, and so I thought it would be helpful to your endeavour if I were to take you through some of my findings.

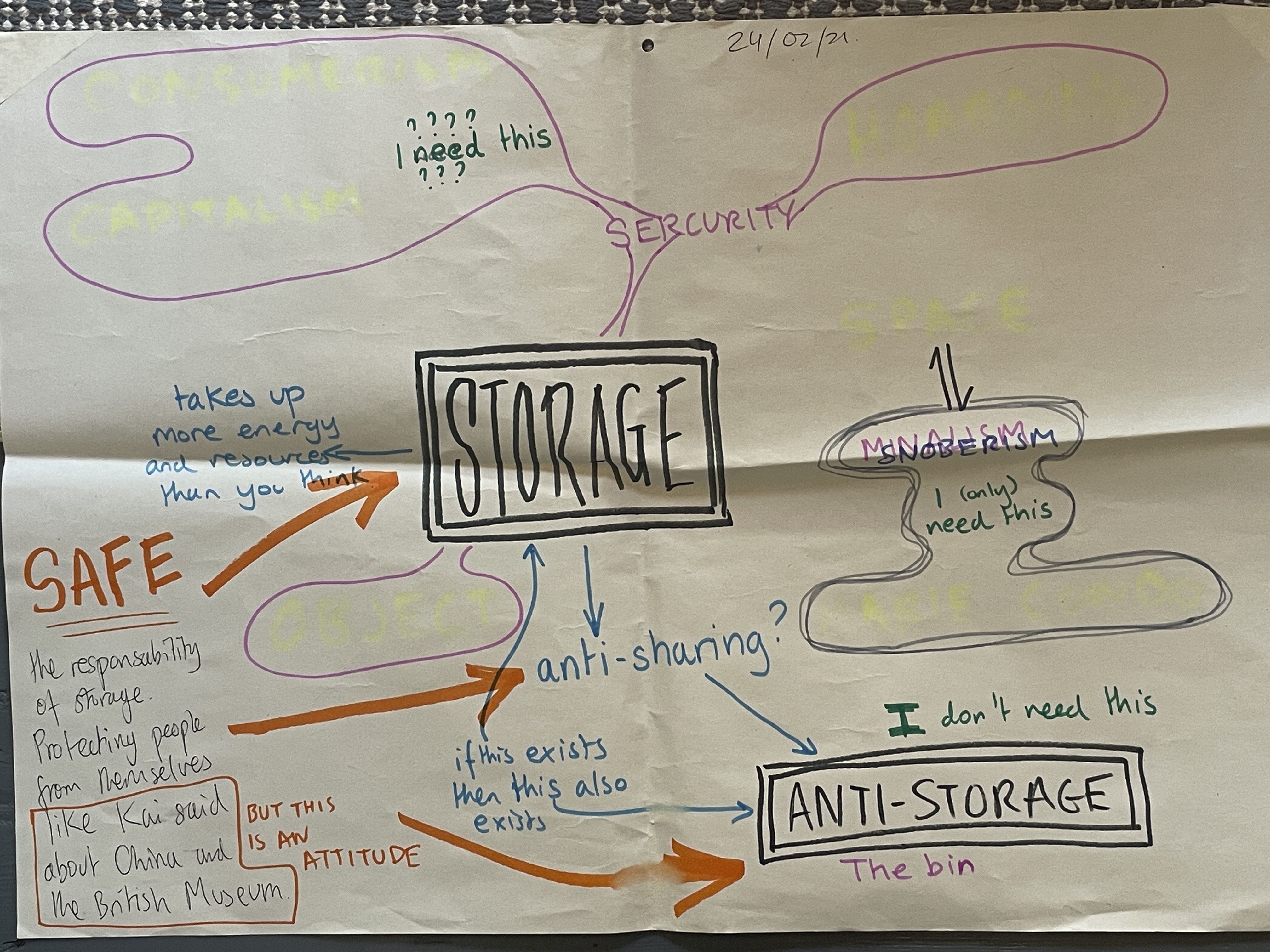

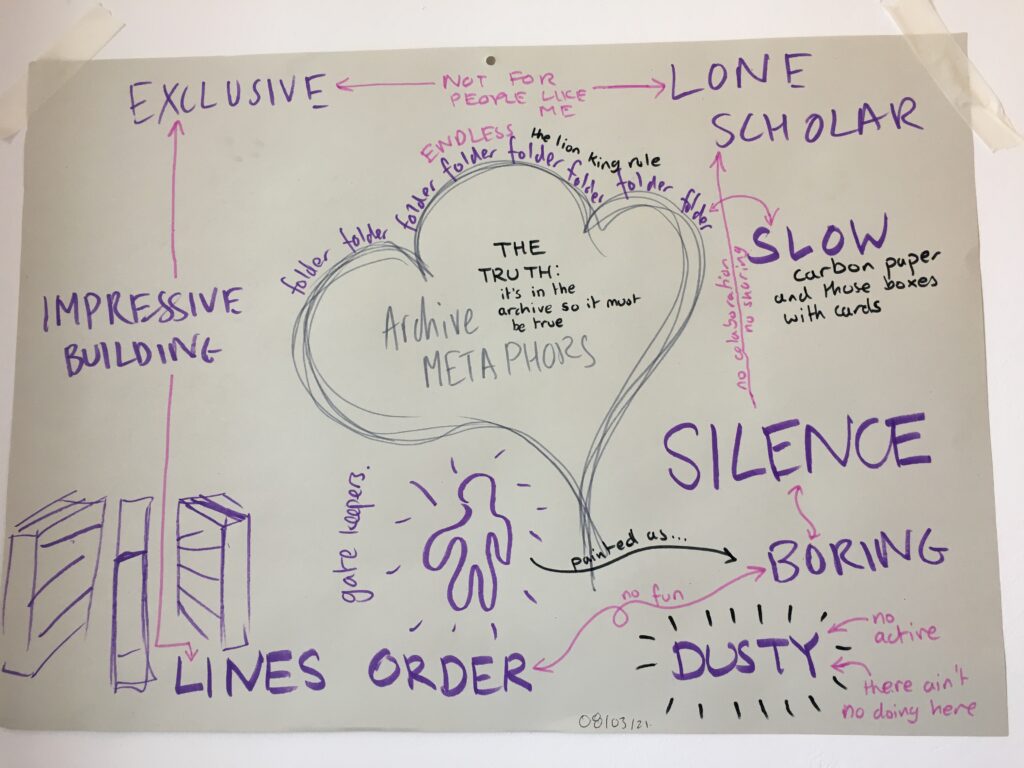

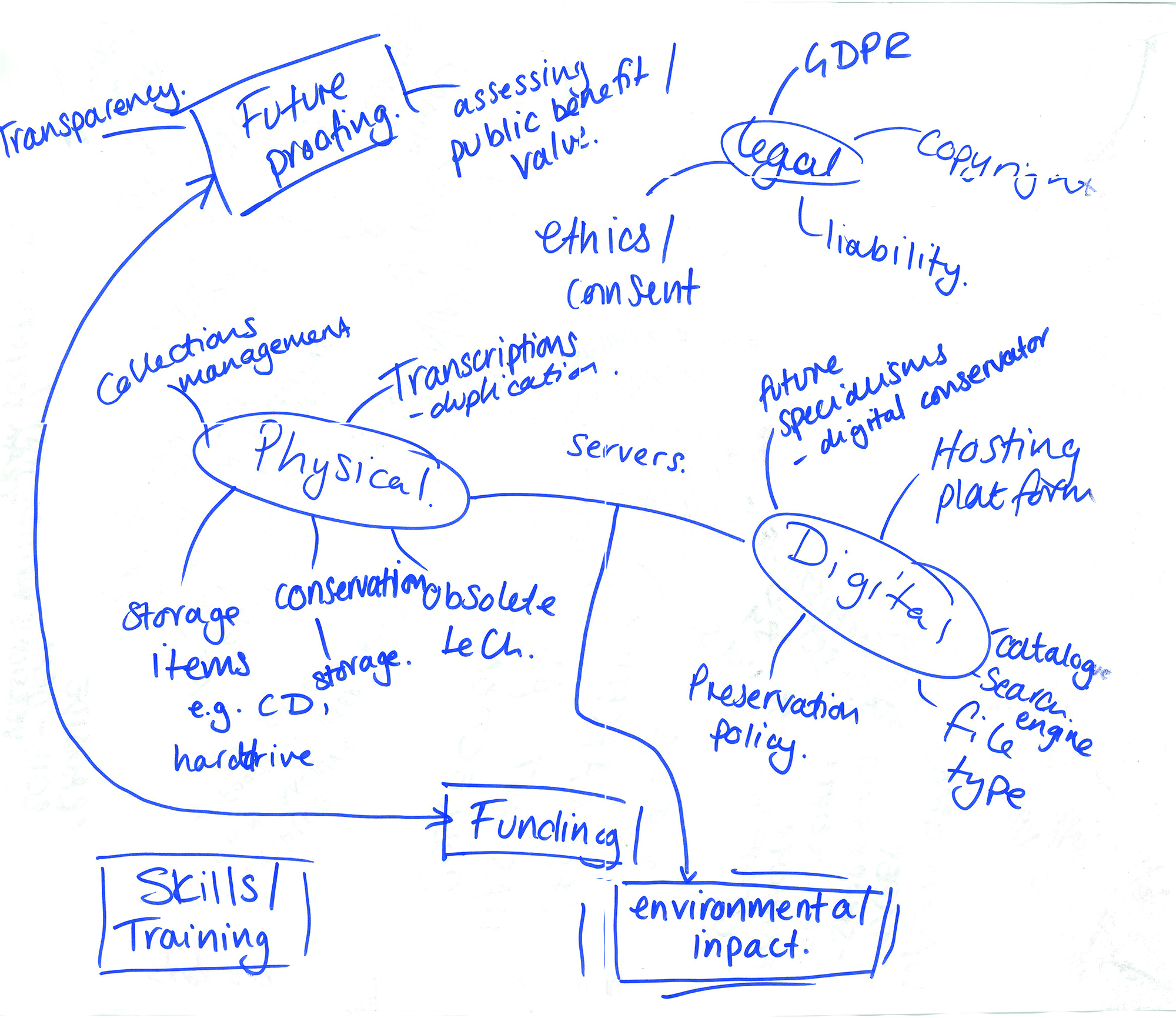

The first thing you need to know about archiving and reusing oral history is that it is a multidimensional problem. In design this is often referred to as a “wicked problem”, a term coined by Horst Rittel and Melvin Webber in their 1973 paper titled, Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning. The term ‘wicked’ is not in reference to the ethical standing of the problems, but is used to capture the difficult nature of the issue, how it is malignant, vicious, tricky, and aggressive. The area of concern is dynamic and interconnected in ways which makes it hard to create a single perfect solution. It is for this reason some designers prefer to use “situation” and “opportunity” instead of “problem” and “solution” as a way to communicate the continual and reflective work that needs to happen when dealing with such complicated situations as the archiving and reuse of oral history recordings. So why am I telling you what a difficult issue archiving oral history is? Well because setting up an oral history programme will require the storing of recording long-term or short-term and as this “deep dark secret” of oral history is something you are guaranteed to come up against and not recognising the complexity of this wicked problem can as Rittel and Webber write could be morally objectionable.

However, you have one distinct advantage when tackling this issue of oral history archiving and reuse – you are not starting form scratch. There have been many attempts to solve the deep dark secret of oral history, some more successful than others which is excellent news as the design theorist Victor Papanek writes, “The history of progress is littered with experimental failures.”.

So to quickly summarise:

- This issue of oral history archiving and reuse is a difficult, multidimensional, and dynamic situation

- There is a long history which we can learn from

Now as I said there are many dimensions on this situation but through my research I have found some general areas which at good starting points for your consideration: technology, ethics, labour, and money. I am going to quickly explain each of these and show how they are interconnected.

I am starting with technology because this is the area which often hogs all the attention, which is not surprising, we like the technological fix, it’s sci-fi, it’s the future, it’s a bit magic. But its magic is an illusion, as Willem Schneider acknowledges in his reflection on the oral history reuse technology Project Jukebox. Technology on its own will not solve the wicked problem of oral history reuse. This is generally for two reasons:

- Firstly it is constantly and rapidly evolving, and tech companies have built obsolescence into their product making technology not a particular stable area which is not helpful when you are setting up an archive or any form of long-term digital storage.

- In addition, the digital world exists as a web of interconnecting systems. Your laptop is made by one company while your software is made by another, and there is another completely different organisation running the internet. If anything happens to one of these systems it is likely to have a ripple effect across the entire networks of interconnected systems. Again this is not a stable environment for long-term storage.

The big lessons we can learn from historical failures are how technology is not the single route to solving the issue and how its unstable nature is one of the greater challenges of this endeavour.

However, technology is also where some of the most interesting opportunities lie. This oral history archive will be created in a post-AI world and therefore will be able to explore how this will affect archives. There is also an increasing awareness of the environmental effects of long-term digital storage and how this is a pressing issue in the age of data.

Next section – Ethics. I have done three different placements for my PhD and in during all of them I was trying to make archival material reusable. I spent those six months not thinking about technology but working on either copyright, data protection, or sensitivity checks. When you are working with oral histories you are dealing with people’s lives, permissions and restrictions have to be in place in order to make it available. And ethics like technology is also always changing. Copyright in the form we know it now was heavily influence by the rise of the internet in the late 20th century. The various data protections laws have only become a thing in the last ten years and definitely will be changing as attitudes change. In addition to this what language and images are deemed socially acceptable is also always changing. The constant evolution of ethics is both a practical challenge and a fantastic research opportunity as this endeavour is working on a very large scale and is a relatively a new geographic area for oral history to be deployed. It is likely setting up the ethics for this project will deliver some new insights into the ethics of oral history archiving in general.

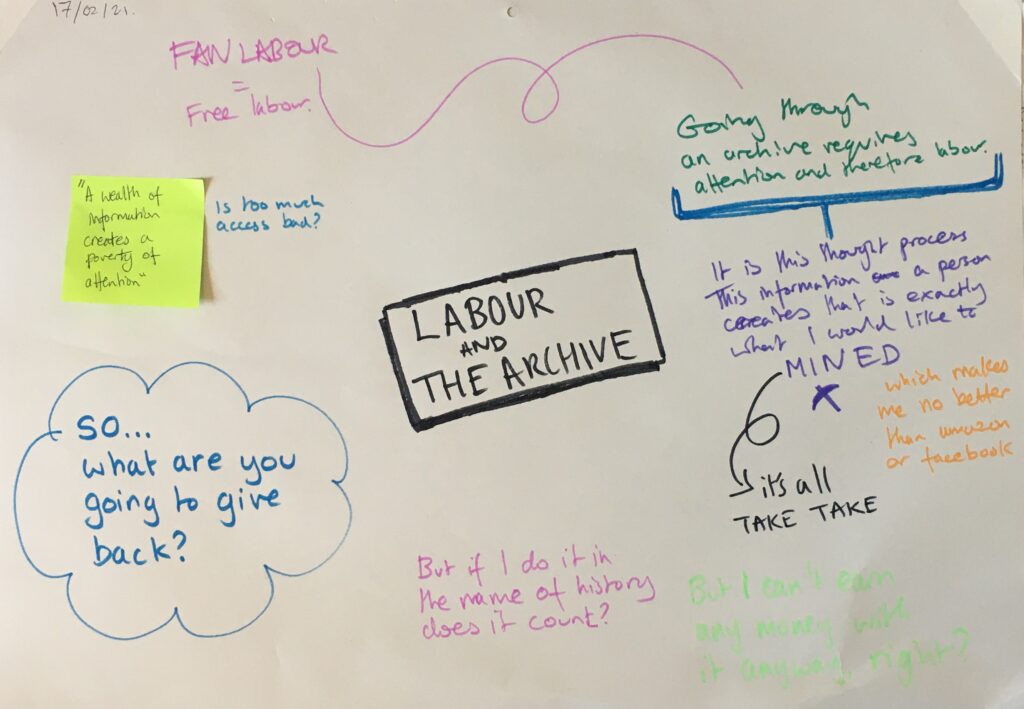

One of my central conclusion of my PhD is how labour, specifically maintenance labour, is critical to successful innovation in this area. Both the areas of technology and ethics will require maintenance labour because they are these continually evolving areas. When we look at some historical attempts to solve this issue we see that some of the technological solutions fail because they did not account for the maintenance it would require to keep the technology. In the case of ethics evolving, one of placements during my PhD required me to do a copyright audit of a large collection. It turn out that out of 1700 recordings only 400 had the correct copyright, meaning that 1300 recordings were not reusable. This likely happened because no one had checked whether these recordings had the right copyright permissions until I came along. In both instances maintenance and the labour it takes to keep long-time storage was not considered and therefore the innovation collapsed or requires a significant amount of restoration. Restoration is only necessary when maintenance fails. In How Buildings Learn Stuart Brand quotes John Ruskin, “Take proper care of your monuments, and you will not need to restore them. Watch an old building with an anxious care, guard as best you may, and at any cost, from every influence of dilapidation.” This endeavour has the great opportunity to explore methods on how to sustain and maintain innovations, by putting labour in a central position. It can give us insights into how organisation are sustained through institutional memory and create ideas on how technology and humans can synthesise their respective abilities to create better long term storage for archival material.

Appropriately the overarching area of tension in this complex issue of oral history archiving and reuse is money. If we look at the history of technology driven solution which failed, many eventually collapsed because people were not maintaining it and people were not maintaining it because they were not getting paid. When the money runs out the work stops and it collapses. And therefore you need to know the budget and consider the long-term requirements of running and maintaining an archive. Here again is an opportunity to develop new forms of spending plans that both encourage innovation and support maintenance, something which currently is not standard practice.

So these four areas are the key starting points to the identifying opportunities to improve the situation around oral history archiving and reuse. Now it is important to note that these are just starting points and each version of the oral history archiving and reuse situation will be different to the next one. Archiving oral history recordings as an small community base project in the country side of England is a different situation to this project and therefore will likely render different opportunities. This is especially the case when you consider how oral history is or be will value within its particular setting. How we value history and historical material will influence how the material is archived and reused. There are many examples with oral history’s legacy where you can clearly see value has shape the project. Certain topics are considered more valuable than others in certain cultures. For example in Europe and the USA the holocaust and the world wars are popular topics for oral history projects. These very intense and heavy topics will bring different ethical issues than lighter topics. Some oral historian’s prefer video recordings over audio recording, another expression of value which will shape the collection. You also have differences in how oral history is valued in relation to other historical materials. Maybe someone uses a photograph in their interview or wishes to record on location, again this will change the set up of collection. All of these decisions will effect what technology might be used, what the ethic forms need to look like, what work needs to be done, where the money can come from. This project needs to understand what it values and how this might shape the project but also how these values might change and how the system will accommodate these changes in value.

The issue of oral history archiving and reuse is not a banal, tame problem. It is a wicked problem – a mess. But it is also an area of great opportunity where great innovation and insights can be discovered if we do not tame the wicked problem but instead seek to identify opportunities which can improve the situation of oral history archiving and reuse for everyone.

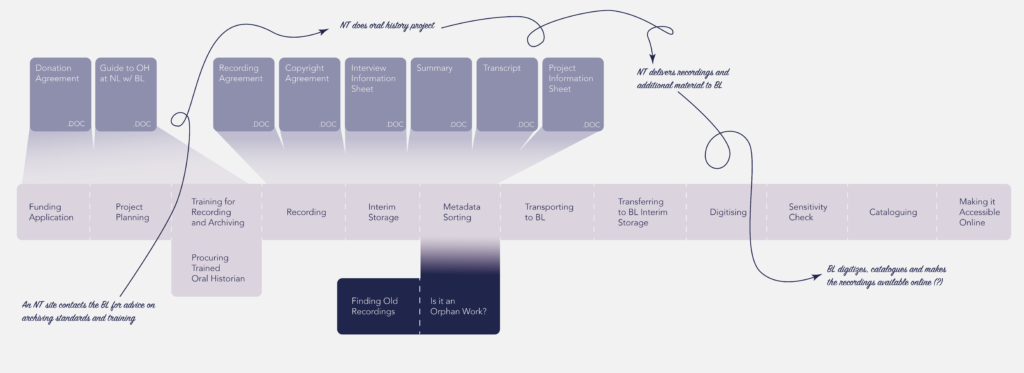

OHD_GRP_0275 Oral history flowchart BL

OHD_WRT_0273 The Trust: stories of the nation

With 1700 recordings of radio programmes, oral history interviews, and field recordings, how many stories lie waiting to be uncovered in the National Trust Sound Collection? In May and June 2023 I carried out an access and copyright audit on the National Trust collection held by the British Library. Although I was in search of signed agreements, I was gripped by the stories, the lived experiences, the contradictory emotions and opinions that are held in this collection. They tell the tales of one of the biggest charities in the country and of the country itself.

The most prominent story in the collection originates from a watershed moment in 1946, when institutions could finance the purchase of important cultural property for the nation through the National Land Fund. The National Trust in particular benefited from the scheme, which allowed the handing over of keys and grounds to the Trust instead of paying estate duty. The effects of the National Trust’s ever-expanding portfolio is covered in a song I came across performed on BBC Radio Four by Kit and the Widow in 1992. “Oh, the National Trust” is a satirical song from the perspective of two volunteers, who sing the tale of a Dowager Duchess of a nameless country house going mad as her home is flooded by National Trust visitors. Eventually the Dowager is sold at Christie’s after her harassment of the visitors becomes too much to bare and she needs to be removed from the property. The song ends with the Dowager’s revenge: she returns as a ghost to haunt her former home and the National Trust. The song neatly covers the stereotypes of the National Trust: the displeased landowner, the busy National Trust volunteers selling tea towels and Beatrice Potter books, and of course, a ghost, the natural partner of any self-respecting country house.

This turbulent period of transition from private ownership to a Trust property is both confirmed and challenged by the contents of other recordings. I found a local resident recalling being chased off a public footpath by an angry landowner, mirroring the Dowager Duchess’ antics. Then there is a former estate owner praising the National Trust taking over their houses because by the mid twentieth century: “the houses were falling down all around the place, nobody could see the future.” What prompted – or forced – owners to give up their home is not always covered in great depth: some interviewees mention death duties as the primary reason to offer their property to the National Trust; a desire to preserve ‘our country’s heritage’ crops up occasionally but seems less of a driver.

Kit and the Widow’s song does not mention an important personal consequence of the transition from private to public ownership: how does the change affect the many people employed on the estates? A significant portion of the interviews in the collection are with people who were former maids, gardeners, butlers, cook, valets, housekeepers etc. The collection therefore captures two elements of the transition story: how the land went from private to public property and how this signified the end of a particular ‘upstairs/downstairs’ system of employment.

Among the more ‘Downton Abbey’ tales in the collection there are interviews which record the role of many stately homes during the two world wars. There are interviews with those immediately affected: evacuees, prisoners of war, the land army, the home guard. Many other recordings reference the period. The government requisition of country houses during the wars is an important chapter in the history the nation’s country estates. Although the importance of this is often acknowledged, there is also a lamentation of the state in which the houses were often left. A gentleman points outs to an interviewer that the priceless wooden panelling is littered with holes, caused by the Land Army workers having their dart board there. The stately homes during this period were neither the grand houses of the wealthy owners nor the tourist attractions they are today: reduced to their basic structures, they functioned as prisons, barracks, and army training camps, where work and play all happened under one roof. Sadly, there are significantly fewer recordings with those directly involved in this period and why this is, remains unknown.

The collection shows how the role of the stately home and grand estate changed over the years but it is not just about people, communities, and social structures. The Director General at the time points out during a radio interview to commemorate the centenary of the National Trust in 1995 that the Trust is not just a ‘keeper of country house’, it actually spends most of its conservation effort on the landscape. Indeed, the National Trust is one of the biggest landowners in the country. They are responsible for landscape from the White Cliffs of Dover to the landscape around Stonehenge (although Stonehenge itself is English Heritage). The collection tells us clearly how our attitude to the land has evolved and how nature has changed as a result of human activity. A speaker recalls seeing the Northern Lights in the Clent Hills in the 1930s before light pollution drowned out the stars. Similarly, the relationship between farming and nature conservation is prominently present in the many interviews with farmers and recordings of Trust staff discussing their policies around farming and conservation. Deer hunting crops up time and again, which in the 1990s was still permitted. Folklore plays a prominent part too; the relationship between the land and tales of ancient witchcraft are plentiful. Yet, in spite of the Director General’s wish to turn the focus away from the National Trust as keepers of country houses, there are distinctly fewer recordings connected to the landscape than there are to country houses.

The National Trust stereotype of the Kit and the Widow song is undeniably a prominent part of the collection. However, when one considers this second biggest oral history collection in the British Library, it is difficult not to be impressed by the sheer scale of the institution. The National Trust is one of the biggest landowners and charities in the UK; the number of stories and histories which come under its care are innumerable. And these are exciting and often fundamentally conflicting stories: there is no single story of the National Trust. Recounting the history and significance of the Trust is always a balancing act in which the many layers of history kept by and embodied in the estates needs to be told from different perspectives. A conflict of interest and a struggle for prominence is present in the current collection, but certain questions that are in the public eye today are notably absent. Nobody asks where the money came from, for example. The colonial pasts of these properties appear absent although it would be an interesting research project to comb the archived recordings for references to colonial ties. And so, let me finish with another few suggestions of stories that could be told or investigated in this collection of cassette tapes and WAV files.

There are few recordings post-2000 so there is little discussion or mention of climate change and the effects it is having on the land, the housing and the Trust’s conservation efforts. Yet, is there evidence of changing nature? The stories and experiences of the National Trust volunteers, the corner stone of the National Trust’s work, are not prominent in the wider collection, but notably start appearing in the more recent recordings. Fundraising efforts is another topic that could be traced, for example, the owners throwing ‘medieval banquets’ as a way of making money. Seaton Delaval Hall, the National Trust property in the North East that I investigate as part of my PhD thesis, was well-known for their themed parties and banquets and many visitors to the property reminisce about the ‘wild nights’. Finally, the many interviews with gardeners and landscape architects are begging to be brought together to create a history of the Trust through gardens. After all, the National Trust tops the European charts for the number of gardens under its wings.

Clips

| Number | Content | Copyright |

| Recordings referenced in the blog post | ||

| C1168/648 | The song “Oh The National Trust” by Kit and the Widow | BBC Radio 4 |

| C1168/144 | Local resident talking about being chase off a public path by the Duchess of Wimpole Estate | No copyright |

| C1168/1605 | Someone talking about Clent Hills | No copyright |

| C1168/618 | Duke of Grafton talking about the National Trust saving the crumble country houses | No copyright (But was NT staff) |

| C1168/1001 | Land army girl at Sutton Hoo | Copyright |

| C1168/526 | NT Director General talking about the Centenary | BBC |

| C1168/819 | NT Director General talking about deer hunting | BBC Radio 2 |

| Recordings that have copyright and might be good for the blog post | ||

| C1168/621 | Coventry, 11th Lord (Family of property owner (before donation to National Trust)) | Copyright |

| C1168/849 | Cocking, Mary (Between Maid) | Copyright |

| C1168/914 | Drane, Jim (AWRE Technician) | Copyright |

| C1168/1108 | Evacuees | Copyright |

Possible Photos

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:National_Trust_Sign_271.JPG

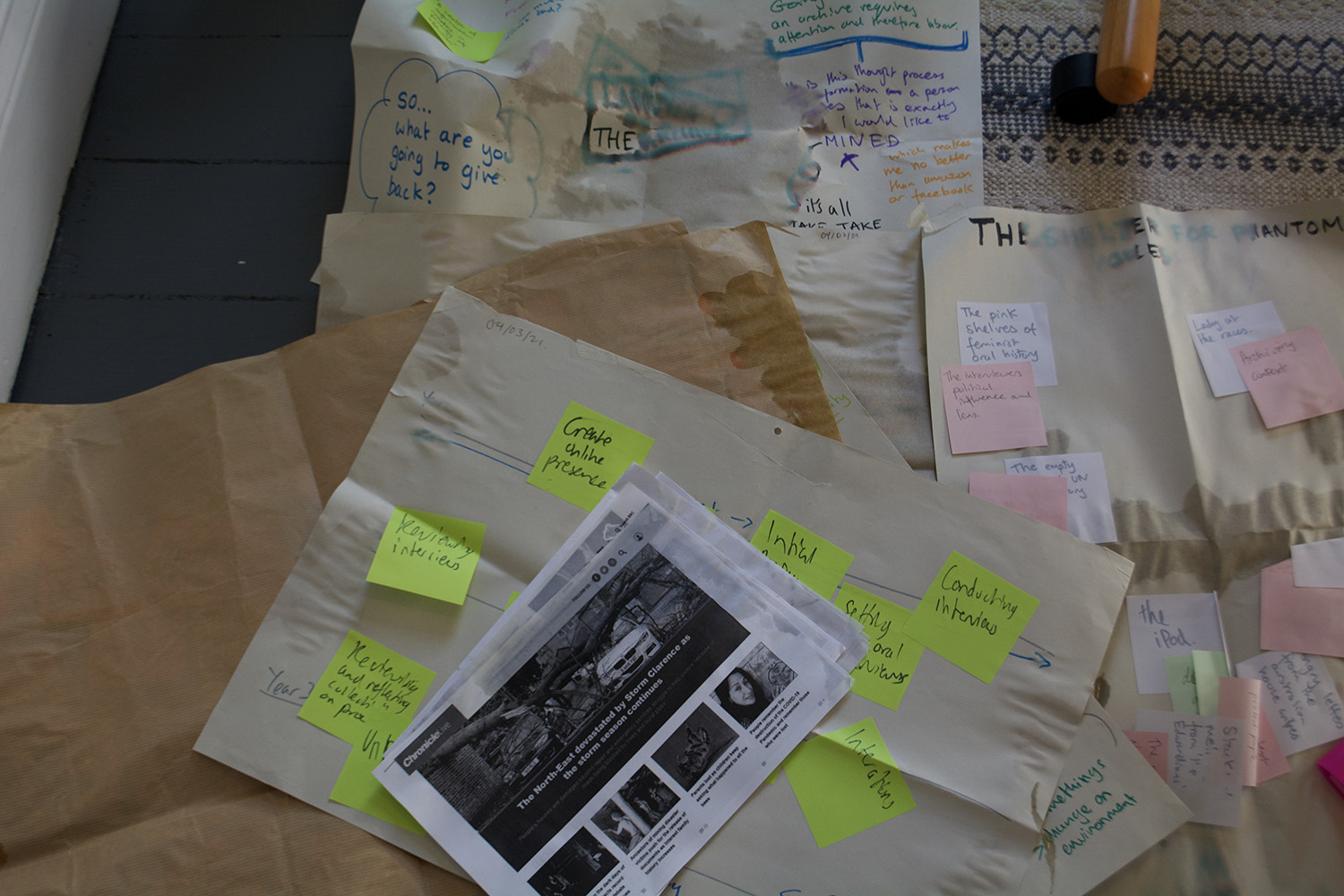

OHD_WHB_0248 Miro board of the archiving workflow

OHD_DSF_0238 Oral history project retention table

| Title of item | Item type | Brief Description | Retention Condition |

| SDH_PP_001_AUDIO | WAV | Oral history recording of Seaton Delaval Hall volunteer. Part of the Research Group. Some memory of the hall before the National Trust. | File to be kept for 25 years and then destroyed. UNLESS accessed and listened to more than five times OR use in a publication, exhibition or similar within the 25 year retention period. If so retention is extended by another 15 years and then reviewed. |

| SDH_PP_002_AUDIO | WAV | Oral history recording of Seaton Delaval Hall staff member. Discusses the COVID-19 pandemic and the Curtain Rises restoration project. | File to be kept for 30 years and then destroyed. UNLESS accessed and listened to more than five times OR use in a publication, exhibition or similar within the 30 year retention period. If so retention is extended by another 15 years and then reviewed. |

| SDH_PP_003_AUDIO | WAV | Oral history recording of previous resident of Seaton Delaval Hall. Lived at the hall from 1947 to 2018. | File to be kept for 40 years and then destroyed. UNLESS accessed and listened to more than five times OR use in a publication, exhibition or similar within the 40 year retention period. If so retention is extended by another 20 years and then reviewed. |

| SDH_PP_004_AUDIO | WAV | Auto-oral history recording of PhD student memories of Seaton Delaval Hall. The student is the interviewer in the other SDH_PP recordings. | File to be kept for 20 years and then transcribed and the audio is destroyed. UNLESS accessed and listened to more than five times OR use in a publication, exhibition or similar within the 20 year retention period. If so retention is extended by another 10 years and then reviewed. |

| SDH_PP_005_AUDIO | WAV | Oral history recording of Seaton Delaval Hall volunteer. Possibly the first National Trust volunteer. Discusses the fundraising for acquisition and the hall before the National Trust. | File to be kept for 20 years and then destroyed. UNLESS accessed and listened to more than five times OR use in a publication, exhibition or similar within the 20 year retention period. If so retention is extended by another 10 years and then reviewed. |

| SDH_PP_006_AUDIO | WAV | Oral history recording of Seaton Delaval Hall volunteer. Discusses the fundraising for acquisition and the hall before the National Trust. Also mentions activist work in local surrounding villages. | File to be kept for 25 years and then destroyed. UNLESS accessed and listened to more than five times OR use in a publication, exhibition or similar within the 25 year retention period. If so retention is extended by another 15 years and then reviewed. |

| SDH_PP_007_AUDIO | WAV | Oral history recording of a person who lived in Seaton Delaval during the war and remembers walking past the Seaton Delaval Hall to Seaton Sluice. | File to be kept for 20 years and then transcribed and the audio is destroyed. UNLESS accessed and listened to more than five times OR use in a publication, exhibition or similar within the 20 year retention period. If so retention is extended by another 10 years and then reviewed. |

| SDH_PP_008_AUDIO | WAV | Oral history recording of a person who did a variety of jobs at Seaton Delaval Hall both before and after the National Trust this included working in the market garden and architectural jobs. | File to be kept for 30 years and then transcribed and the audio is destroyed. UNLESS accessed and listened to more than five times OR use in a publication, exhibition or similar within the 30 year retention period. If so retention is extended by another 15 years and then reviewed. |

| SDH_PP_009_AUDIO | WAV | Oral history recording of the eight vicar of the Seaton Delaval parish telling tales of the Church of Our Lady on the Seaton Delaval Hall property. | File to be kept for 40 years and then transcribed and the audio is destroyed. UNLESS accessed and listened to more than five times OR use in a publication, exhibition or similar within the 40 year retention period. If so retention is extended by another 20 years and then reviewed. |

| SDH_PP_010_AUDIO | WAV | Oral history recording of Seaton Delaval Hall volunteer. Discusses a lot of the fundraising for acquisition and research into the hall. | File to be kept for 20 years and then transcribed and the audio is destroyed. UNLESS accessed and listened to more than five times OR use in a publication, exhibition or similar within the 20 year retention period. If so retention is extended by another 10 years and then reviewed. |

| SDH_PP_001_TRANSCRIPT | Transcript of oral history recording of Seaton Delaval Hall volunteer. Part of the Research Group. Some memory of the hall before the National Trust. | File to be kept for 40 years and then printed off. UNLESS accessed and listened to more than ten times within the 40 year retention period. If so retention is extended by another 20 years and then reviewed. | |

| SDH_PP_002_TRANSCRIPT | Transcript of oral history recording of Seaton Delaval Hall staff member. Discusses the COVID-19 pandemic and the Curtain Rises restoration project. | File to be kept for 40 years and then printed off. UNLESS accessed and listened to more than ten times within the 40 year retention period. If so retention is extended by another 20 years and then reviewed. | |

| SDH_PP_003_TRANSCRIPT | Transcript of oral history recording of previous resident of Seaton Delaval Hall. Lived at the hall from 1947 to 2018. | File to be kept for 40 years and then printed off. UNLESS accessed and listened to more than ten times within the 40 year retention period. If so retention is extended by another 20 years and then reviewed. | |

| SDH_PP_004_SUMMARY | Summary of auto-oral history recording of PhD student memories of Seaton Delaval Hall. The student is the interviewer in the other SDH_PP recordings. | File to be kept for 30 years and then printed off. UNLESS accessed and listened to more than ten times within the 30 year retention period. If so retention is extended by another 20 years and then reviewed. | |

| SDH_PP_005_TRANSCRIPT | Transcript of oral history recording of Seaton Delaval Hall volunteer. Possibly the first National Trust volunteer. Discusses the fundraising for acquisition and the hall before the National Trust. | File to be kept for 40 years and then printed off. UNLESS accessed and listened to more than ten times within the 40 year retention period. If so retention is extended by another 20 years and then reviewed. | |

| SDH_PP_006_TRANSCRIPT | Transcript of oral history recording of Seaton Delaval Hall volunteer. Discusses the fundraising for acquisition and the hall before the National Trust. Also mentions activist work in local surrounding villages. | File to be kept for 40 years and then printed off. UNLESS accessed and listened to more than ten times within the 40 year retention period. If so retention is extended by another 20 years and then reviewed. | |

| SDH_PP_007_SUMMARY | Summary of oral history recording of a person who lived in Seaton Delaval during the war and remembers walking past the Seaton Delaval Hall to Seaton Sluice. | File to be kept for 30 years and then printed off. UNLESS accessed and listened to more than ten times within the 30 year retention period. If so retention is extended by another 20 years and then reviewed. | |

| SDH_PP_008_SUMMARY | Summary of oral history recording of a person who did a variety of jobs at Seaton Delaval Hall both before and after the National Trust this included working in the market garden and architectural jobs. | File to be kept for 30 years and then printed off. UNLESS accessed and listened to more than ten times within the 30 year retention period. If so retention is extended by another 20 years and then reviewed. | |

| SDH_PP_009_SUMMARY | Summary of oral history recording of the eight vicar of the Seaton Delaval parish telling tales of the Church of Our Lady on the Seaton Delaval Hall property. | File to be kept for 30 years and then printed off. UNLESS accessed and listened to more than ten times within the 30 year retention period. If so retention is extended by another 20 years and then reviewed. | |

| SDH_PP_010_SUMMARY | Summary of oral history recording of Seaton Delaval Hall volunteer. Discusses a lot of the fundraising for acquisition and research into the hall. | File to be kept for 30 years and then printed off. UNLESS accessed and listened to more than ten times within the 30 year retention period. If so retention is extended by another 20 years and then reviewed. | |

| SDH_PP_METADATA | Spreadsheet of the SDH_PP oral history recordings’ metadata, includes interview length, location, equipment, and tags. | File to be kept for 30 years and then printed off. UNLESS accessed and listened to more than ten times within the 30 year retention period. If so retention is extended by another 20 years and then reviewed. | |

| SDH_PP_PROJECT_SUMMARY | Document by the SDH_PP interview on the project. Includes a brief summary on process and their reflection on the project. | File to be kept for 40 years and then printed off. UNLESS accessed and listened to more than ten times within the 40 year retention period. If so retention is extended by another 20 years and then reviewed. |

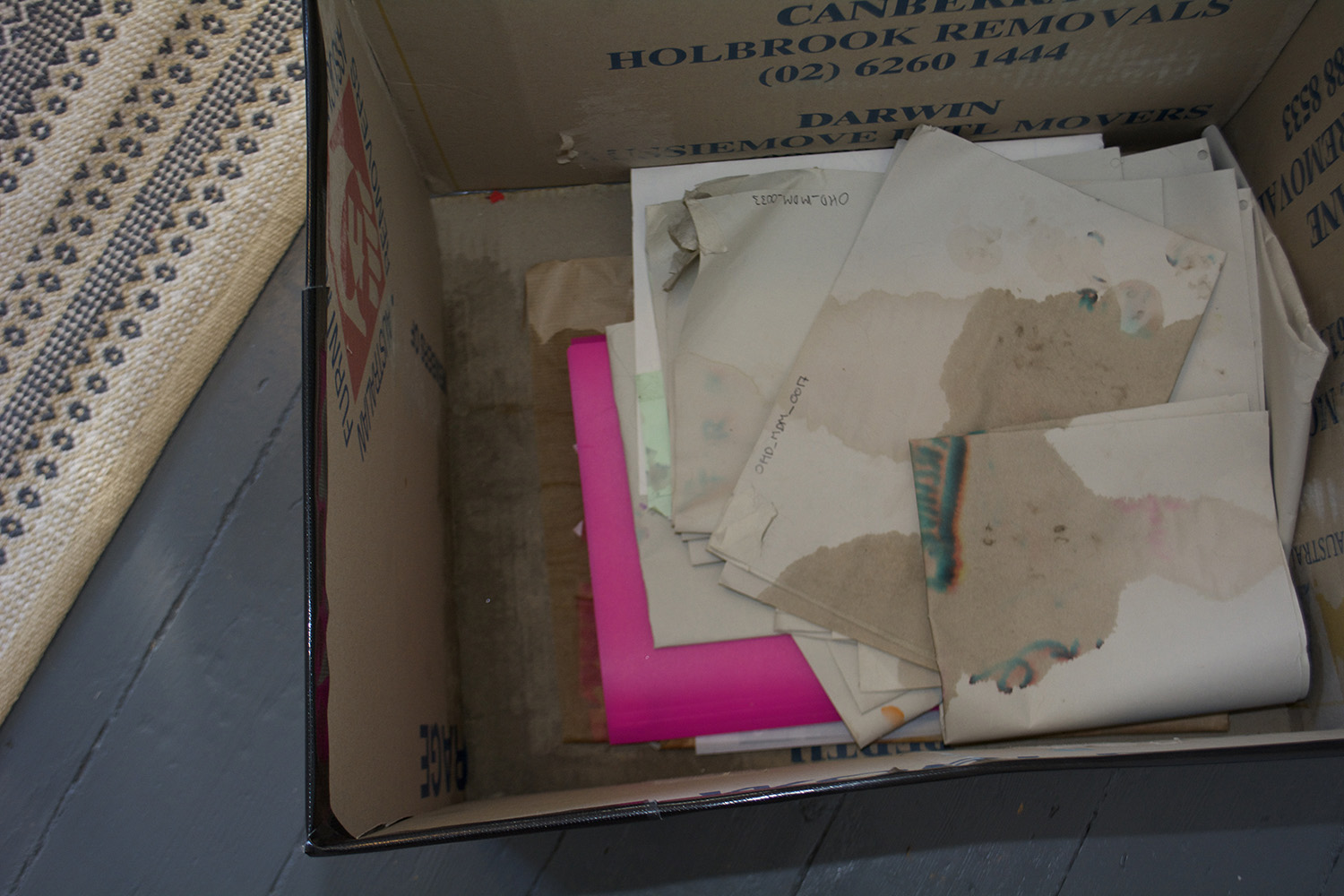

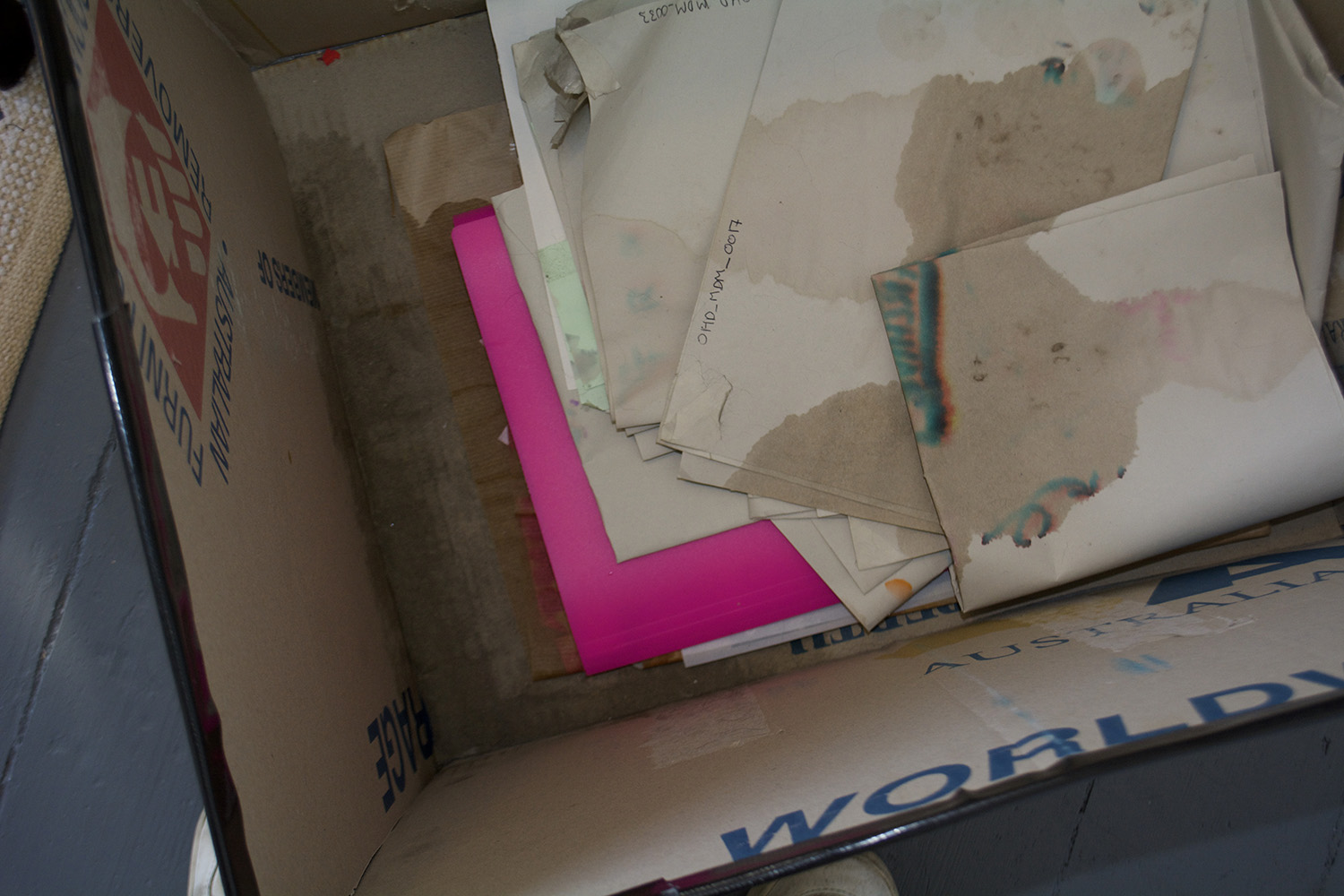

OHD_PRT_0038 Archive Box 1

OHD_BLG_0034 21st Century Ghost

Have you ever heard of the twenty-first century ghost? You have definitely seen it and heard it. It hides in many places, but its favourite spot is in the pocket of your trousers, next to you on the table or in the palm of your hand. The ghost of the twenty-first century lives in the interactive rectangle that is your smart phone. This ‘digital urn’, as described by Kirsty Logan in the podcast series A History of Ghosts, is filled with your voice, your face, your ideas, your questions, your life. Every day we work on growing our own twenty-first century ghost by feeding it incredibly personal information and preserving it in our digital urn. But our twenty-first century ghosts’ range is not limited to our smart phones, they spread across the world, roaming around social media servers and traveling in the inboxes of other people’s digital devices. The average person has no control over what can be found in their digital urns, what past lives the ghost can expose and havoc it can cause.

Some people have a different type of ghost, one that is a little more timid and introverted. If you have ever taken part in an oral history project you probably have such a ghost; a recording of your life’s story told by you living in an archive staying put until someone calls on it. In order to put an oral history interview into an archive and create an archival ghost, one has to fill in what seems endless ethical approvals, consent forms and permission slips. These documents are there to highlight the potential “dangers” of having something in an archive: how you privacy might be violated or how someone could misuse your testament and twist your words. Social media sites do a similar thing, only they condense the stacks of paper into one tick box. Clearly the archiving process is more transparent in comparison to the methods use by those in the Silicone Valley, which at best are questionable and at worst violate basic human rights, however transparency does have its drawbacks.

The reaction people have to this transparency is similar to that when you ask some people to travel by air. People are terrified of flying because they are fully aware of how wrong it can go, but statistically it is a lot safer than walking to the corner shop. Just like the designing an aeroplane, archiving an oral history has to follow certain rules from the start, because those involved, aerospace engineers and oral historians, are fully aware of the chaos and pain it could cause if the systems fail. Having these restrictions is seen as more ethical, but it also inadvertently puts disproportionate emphasis on the dangers of archiving (and flying). In opposition, walking, like the ticking of the terms and conditions box, is easier and it delivers blissful ignorance to the high probability of being hit by a car or having one’s data stolen. Unlike the oral historians and archivists, the developers of the uncomplicated tick box view their users as nothing more than data sets and potential profit. Some could say that this has led them to be dismissive of a human’s right to privacy and be vague when it comes to revealing the true cost of using one of their platforms. However it seems that by not drawing attention to terms and conditions, people have become very happy to hand over their personal information.

The existence of these two ghosts, the restricted and timid archival ghost, and the free and uncontrollable twenty-first century ghost, makes the people’s relationship to their privacy seem incredibly distorted and ill-informed. It seems odd to trap the archival ghost with paperwork in order to protect their corresponding human, when that exact human is completely content with sharing every single part of their lives with strangers on the internet. However, it is this sharing that is key to success of social media. By giving up their privacy the users of social media are granted access to a huge network of listeners and viewers. After all a story is not a story if there is no one to listen to it. By the same logic if the oral history is never reused, the archival ghost is never called upon and the story is never listened to, its very existence becomes void. So this raises the question: should we even bother archiving oral histories in the first place if the paperwork blocks it off from listeners? For the sake of my research we’ll say yes, in which case let’s follow it up with the question: should we be more like Silicone Valley and be a little less pedantic when it comes ethics?

For now I am going to go with yes and no. The current process around ethical archiving does need updating but because I also fundamentally believe that Silicone Valley is wrong and I think people are starting to catch on. People are becoming increasingly aware of what their twenty-first century ghost might expose. For example, a growing number of people are being ‘cancelled’ because the public have dug through their digital urn and found a tweet they sent when they were twelve and used a term that is now considered very derogatory. There is also a generation of people, who are unhappy with their parents relentless ‘sharenting’. Sharenting is the practice of posting everything your child does online, which results in the child having a data presence before they can even speak and therefore give consent to its existence. This faint atmosphere of mindfulness around posting, uploading and sending is descending over the digital world. People are reflecting on the ghosts they have created and are now trying to do damage control.

Currently the archival ghost and the twenty-first century ghost are two extremes on the scale of privacy and its corresponding ethics. However, the increased awareness around the rabidness of the twenty-first century ghost is pushing it along the scale in the direction of the archival ghost. I believe it is now the turn the archival ghost to make a similar move towards the centre. There needs to be more innovation when it comes to the ethics of archiving because at present it is stopping people listening back and that is truly a shame. People bond over sharing stories, they create communities around the most random of things and social media proves this. However social media also showcases perfectly the consequences of condensing very complicated ethics into one tick box for the sake of ease. Changes need to be made on both sides of the scale. By observing the current situation on each side, investigating the pitfalls, challenges and opportunities, and reviewing how different people in the respective fields are attempting to solve these problems, we can start seeking an equilibrium and find a balance between private and public. This managing of our ghosts is a strange and distorted process that is only in its infancy, but hopefully by the end we will be able to free the locked up archival ghost and calm the twenty-first century ghost.

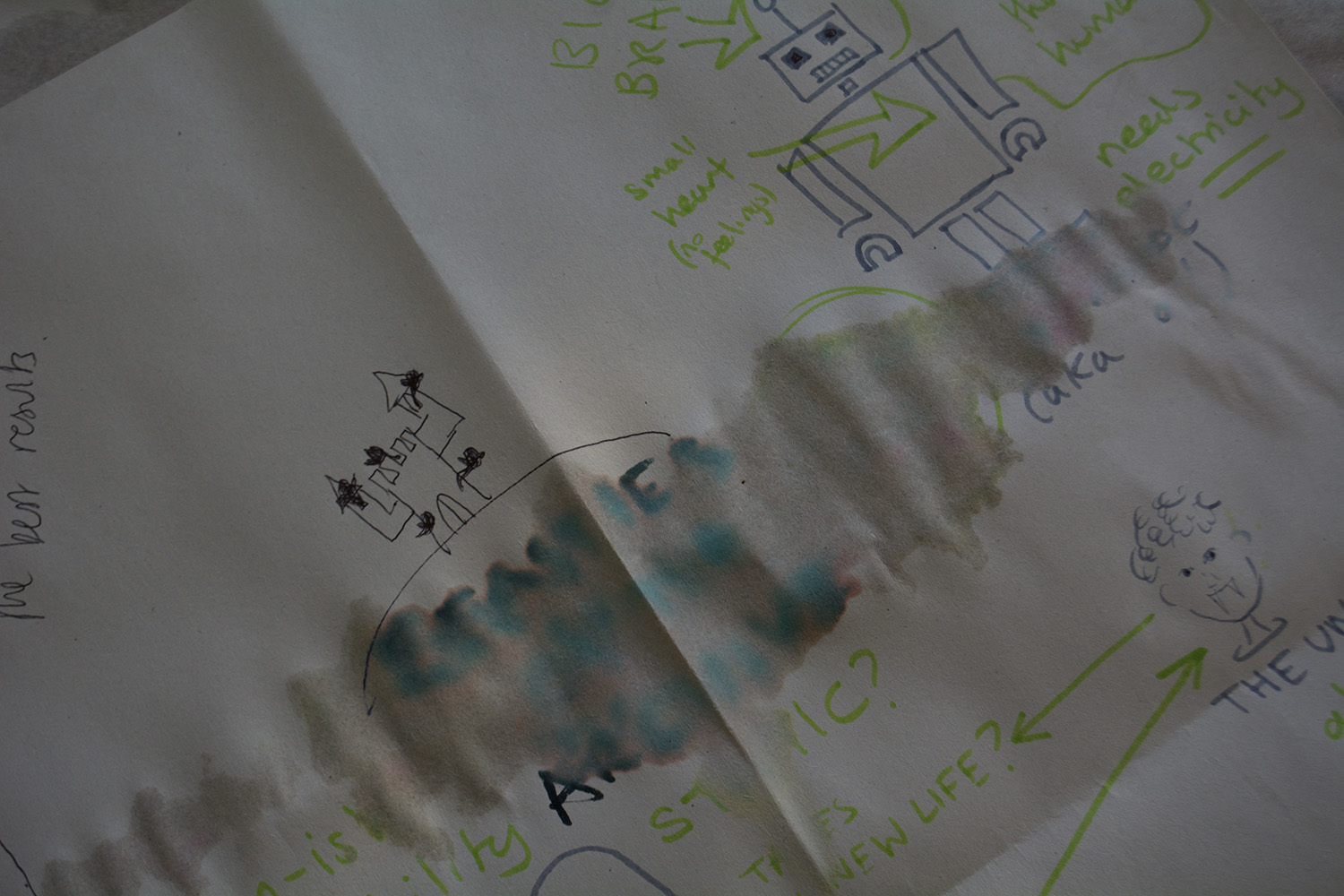

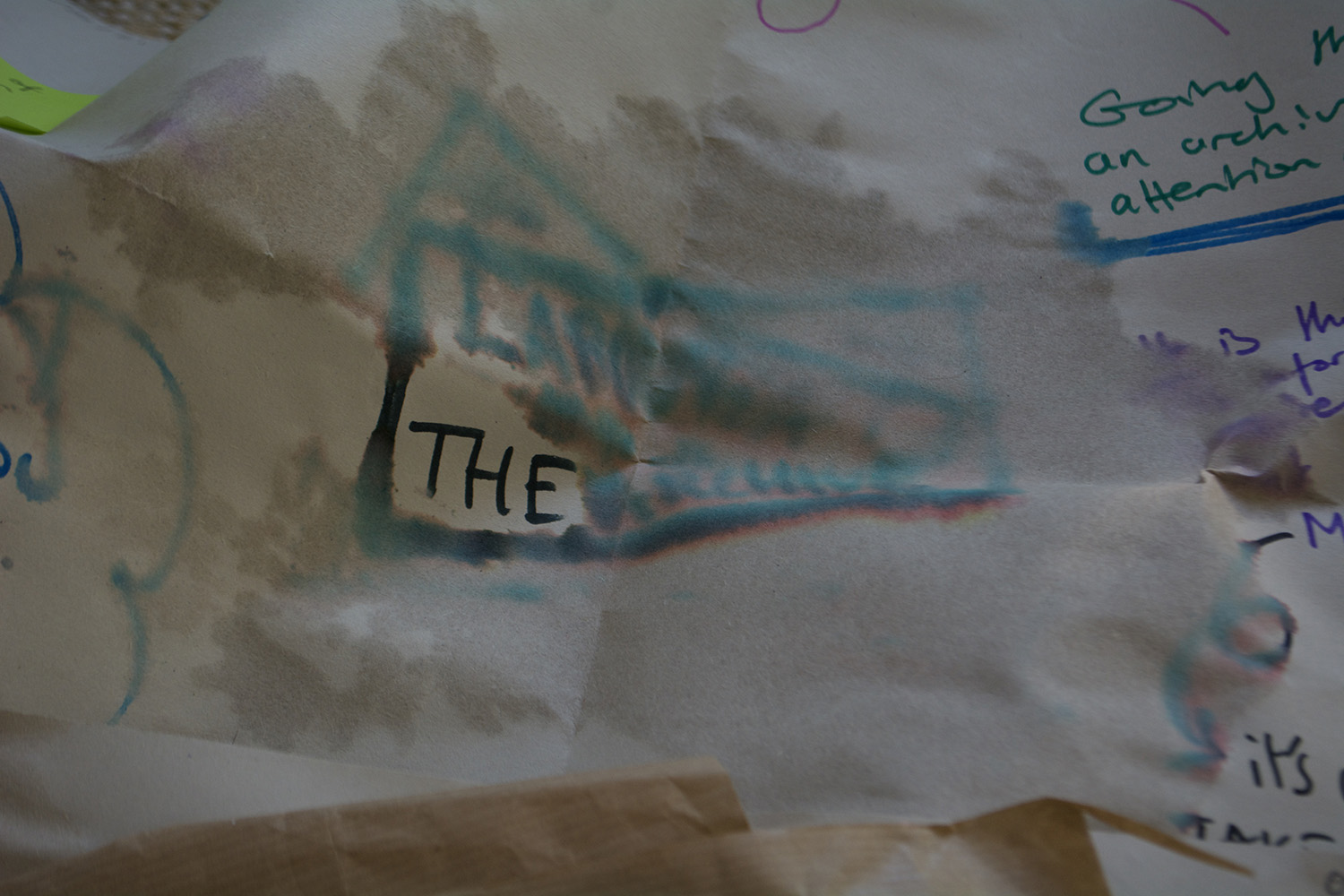

OHD_WKS_0208 NT Oral History Workshop

The overal aim of this workshop is to understand the value of oral history to heritage sites and understand the resources needed to safely store and exhibit these oral histories

Activity One: Oral History Braindump

Aim: To understand the value of oral history to heritage sites.

Task: To start with the participants will be asked to “dump” all the times they have listen to an oral history good or bad. They will then pick out the positive or negative feelings they had while experiencing these oral histories in an effort to understand the value of listening to oral history.

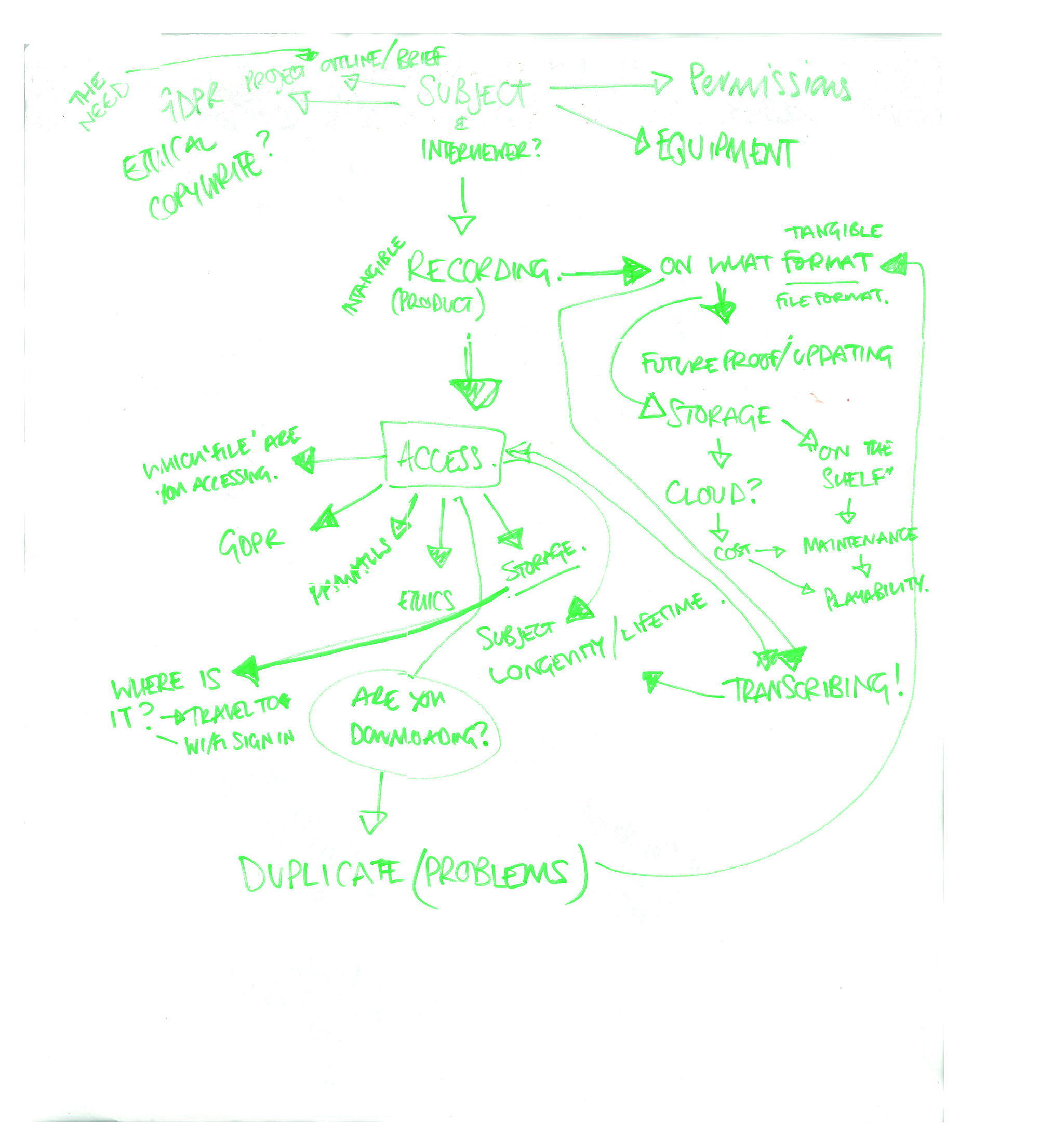

Activity Two: Breaking down an oral history recording

Aim: To understand what we need to do to make and keep an oral history recordin

Task: First, the participants will be asked to think about is needed to make an oral history recording. Then they will be asked what is necessary to keep an oral history recording.

Activity Three: What are we going to make?

Aim: To come up with ideas for the use of oral history by drawing on the two previous activities

Task: The participants are asked to come up with ideas that best display the value of oral history but also consider the resources, labour and ethics that are involved with handling an oral history.

Activity three was never completed

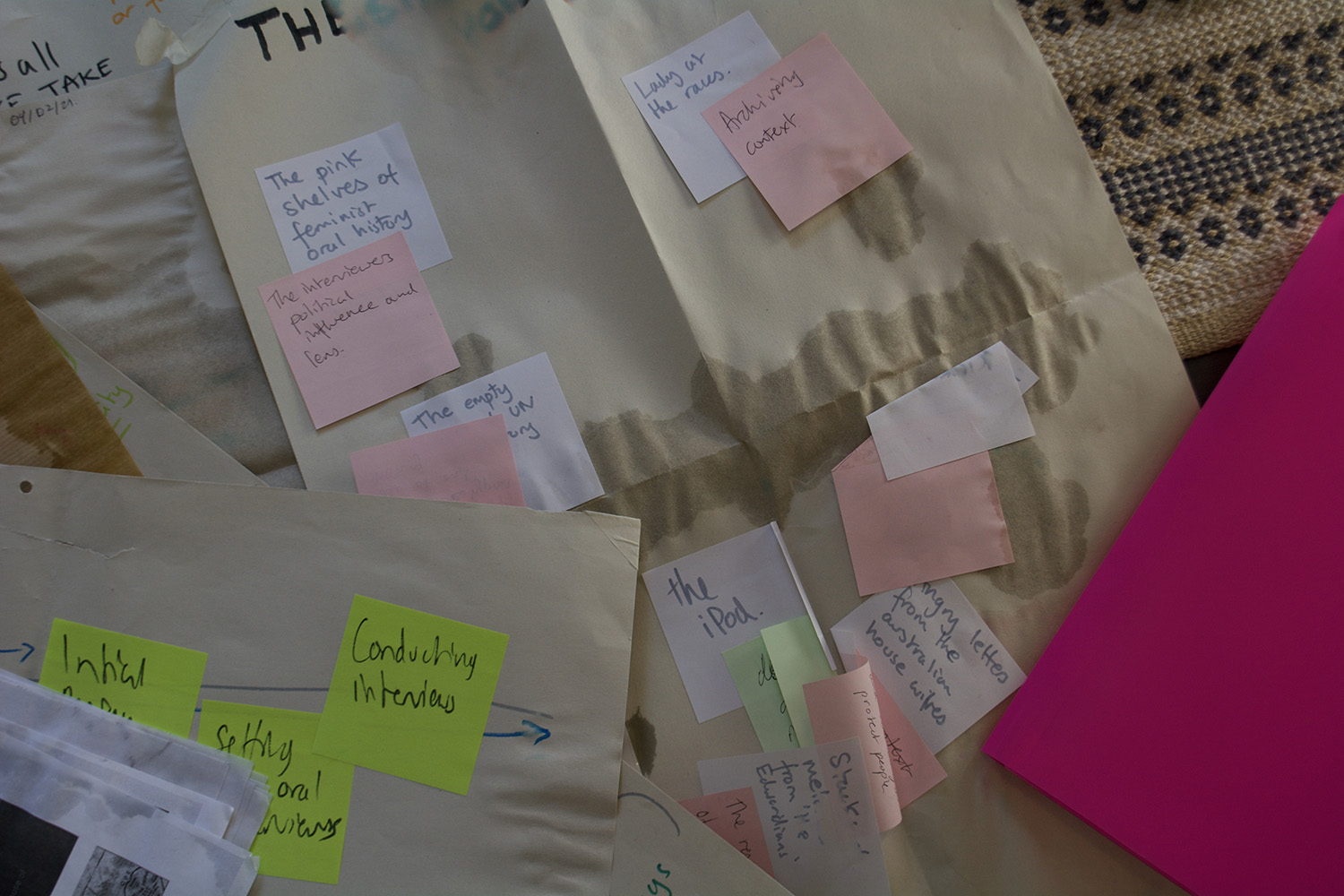

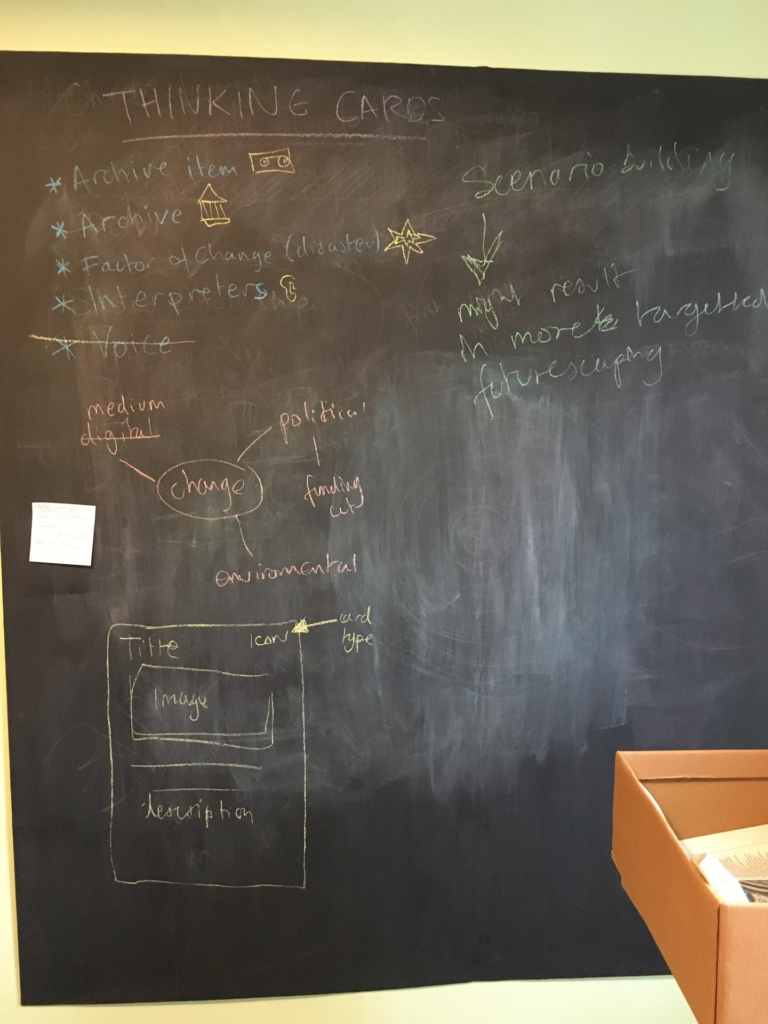

OHD_WKS_0204 THINKING CARDS: How would you archive this?

How would you archive this?

– a interview that is closed off for 30 years but is digital

– with transcript

– with photographs analogue

– about gender

– about race

How would you access this?

TASK:

Start conversations around how we archive things

AIM:

Collect experts’ opinions on strange archiving situation

TYPES OF CARDS

ARCHIVE

– KGB archive

– British Library

– https://www.alternativetoronto.ca/archive/about

– https://creativememory.org/en/archives/

– TWAM

– Black archive

ARCHIVE ITEM

– A wax cylinder recording of an aboriginal voice

– Australian housewives

– Sex workers

– Transperson

– UN oral history

– Lady at the races

– The Edwardians

– With photographs

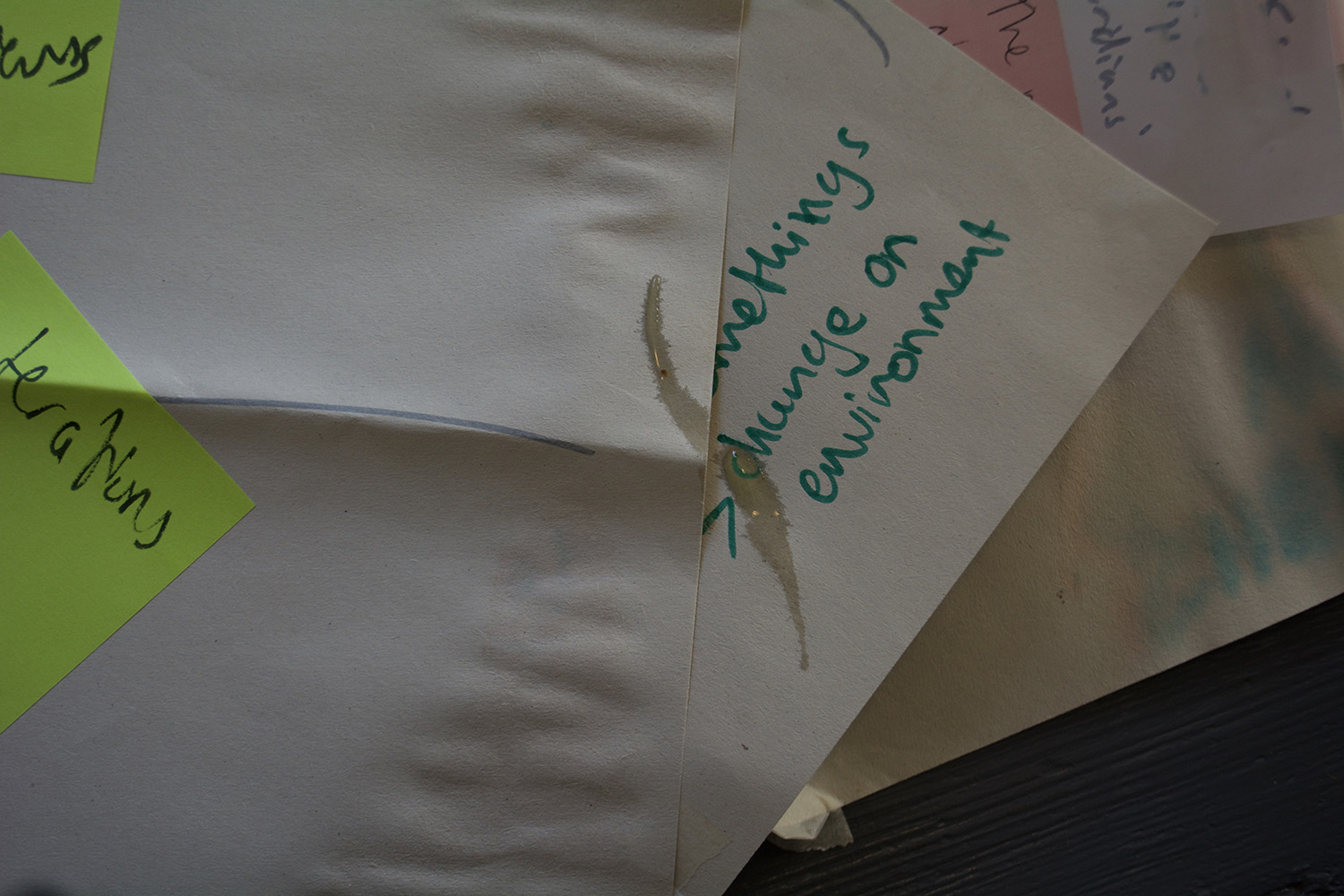

CHANGE

– Terrorism

– Fire

– Flood

– Earthquake

– Malware

– Ethnic cleansing

–

fire, accidental

fire, arson

flooding, from outside flooding, from inside earthquake

other ‘natural causes’

armed conflict

removed by occupying forces civil disorder

terrorism

inherent instability

bacteria, insects and rodents mould and humidity

dust

pollution

bad storage

lack of restoration capacity bad restoration

neglect

while moving offices administrative order unauthorised destruction theft

use

INTERPRETERS

– Podcasters

– Journalist

– Artist

– Writers

– Film makers

– Creators

– Investigators

– Historians

– Family

– People in search of identity