The aims of the placement at British Library were:

For the first aim I did an audit and presented my findings in a spreadsheet. The creation of this audit included searching through both analogue and digital files. The audit has given the staff at The British Library a better idea of what material still needs to be catalogue, digitised, and ingested, and which recordings need be to prioritise within each of these. For example, I found a handful of mini-discs which are harder to digitise then cassette tapes. The second aim of the placement lead me to create another audit, this one specifically about the copyright status of all the recordings in the catalogue. This was a long and tedious process which took up most of my time during this placement. It required me to be very thorough and rigorous as I had to repeatedly go through the recordings accompanying documents in order to check and double check whether the recording had copyright or not. In the end the auditing process produced one very large spreadsheet, containing information on all the recordings, and a spreadsheet for each individual National Trust property which had a recording without copyright. In addition to noting whether a recording had copyright or not I also had to work out whether an item could be an orphan work. Doing these two audits help me better understand the workflow within an archive and what is needed to make archival material accessible. In addition, to these two audits I also created a guide to what I had done so the person who next works on the National Trust’s sound collection can easily understand what I did and why. This was a very helpful exercise as it made me think about how you might communicate across project periods or other long periods of time and ensure work and information is not lost or repeated.

Overall this placement gave me a better idea of The British Library and the National Trust’s relationship surrounding oral history story. The National Trust sound collection is the second biggest in the archive and the recordings span nearly 40 years, so there is a great variety in needs when it comes to preservation and steps to make material accessible. The work I did while on this placement has become a foundation for further projects based around the National Trust sound archive, including the further cataloguing of analogue and digital material, and the development of a three-month PhD placement which will involve developing a workflow for National Trust sites to obtain the correct copyright forms and help The British Library in getting closer making the recordings publicly available.

Finally, I also wrote a report on the status report on the collection to share with both National Trust and British Library staff and have also written a blog post on the contents of the collection after I spent the last week listening to a handful of recordings.

Tranche 10 [G: Drive]

Property: Batemans

Folder contains:

One spreadsheet – which indicates four recordings on CDs transferred from mini disc

Four PDFs – scans of permission forms, summary, transcript and additional material

Property: Mottisfont (and Stockbridge?)

Folder contains:

One spreadsheet – which has 7 entries but only three are fully described. The NT reference is NT10678. There is also an additional sheet in the document for “Stockbridge” which has one entry with the NT code NT10924-001

Three word documents – summaries for interview with Derek Hill (NT reference NT10678-002), Prof. Rosalind Hill (NT10924-001, the Stockbridge one) and an BBC interview with Derek Hill (NT10678-004)

Property: Mottistone

Folder contains:

One spreadsheet – single entry NT10679

Tranche 11 (Knole) [G: Drive]

Property: Knole

Folder contains:

A single spreadsheet with 73 entries

C1168 Tranche 11 [N: Drive]

Property: Knole

Folder contains:

73 folders – each folder corresponds to an entry in the spreadsheet on the G: Drive folder “Tranche 11 (Knole). Each folder generally contains consent form, interview data sheet, timed content summary and the audio recording

Tranche 12 (Southwell) [G: Drive]

Property: Southwell

Folder contains:

One folder with 95 copyright forms and a spreadsheet of oral history interview metadata with 77 entries. The difference in the total of copyright forms to spreadsheet entries is likely due to some recordings having two or more interviewees. However the reference numbers for the recordings also seem to skip between NT10985—058 and NT10985—072 which could suggest files are missing although this is complete speculation. There are two entries for Brian Kay but this seems to be a mistake and one should be Paula Clifford. For nine of the entries I had not been able to locate any files these are:

Adkin, Margaret

Bowler, David

Cotterill, L

Gaunt, William

Knobham, Lily

Pitchford Diana

Ryan, Wendy

Thomas, Doris

Wright, Frederick

C1168 Tranche 12 [N: Drive]

Property: Southwell

Folder contains:

“OneDrive_1_05-10-2020” – the interviews on ten interviewees, one has an interview summary and the other seems to have additional written material. Two only have mp3s files. None of these names are found in the spreadsheet in the folder “Tranche 12 (Southwell)” in the G: Drive but their copyright forms are in the folder “copyright assignment” in in the folder “Tranche 12 (Southwell)” in the G: Drive.

Adamson, Louise

Ball, Samantha

Grice, Irene

Hancock, Peter

Kemp, Trevor

Kent, Pauline

Manning, Michael

Nicholls, Angela

Powell, Rosemary

Williamson, Neil

“OneDrive_1_25-09-2020” – 10 tapes with summary sheets in word doc format. Lynne Bush and Dorothy Bush are the same person. These are found in the spreadsheet in folder “Tranche 12 (Southwell)” in the G: Drive and their copyright forms are in the folder “copyright assignment” in in the folder “Tranche 12 (Southwell)” in the G: Drive.

“OneDrive_2_25-09-2020” – 19 interviews with summaries and one extra summary sheet for Hughes, Daphne and Stanley. These are found in the spreadsheet in folder “Tranche 12 (Southwell)” in the G: Drive and their copyright forms are in the folder “copyright assignment” in in the folder “Tranche 12 (Southwell)” in the G: Drive.

“OneDrive_3_25-09-2020” – the audio for ten interviewees some do not have summary sheets and the is one lone summary sheet for Kay, Brian. These are found in the spreadsheet in folder “Tranche 12 (Southwell)” in the G: Drive and their copyright forms are in the folder “copyright assignment” in in the folder “Tranche 12 (Southwell)” in the G: Drive.

“OneDrive_4b_25-09-2020” – One interview in Mp3 format, 15 in WAV. Only six have summaries. These are found in the spreadsheet in folder “Tranche 12 (Southwell)” in the G: Drive and their copyright forms are in the folder “copyright assignment” in in the folder “Tranche 12 (Southwell)” in the G: Drive.

“OneDrive_5_27-09-2020” – 14 interviews no summary sheets. One additional document in PDF format. These are found in the spreadsheet in folder “Tranche 12 (Southwell)” in the G: Drive and their copyright forms are in the folder “copyright assignment” in in the folder “Tranche 12 (Southwell)” in the G: Drive.

C1168 Tranche 13 [N: Drive]

Property: Clumber Park

Folder contains:

Material from one interview with Peter Stevenson, including permission forms, transcript and WAV file

Cupbooard

Tranche 5

Properties: A lot

Box 1 – Contains loads of CDs which are also found in the folder “C1168 Tranche 5” on N: Drive. HAS BEEN CATALOGUED but the CDs have not been given BL catalogue codes.

Box 2 – Contains CDs of recordings which are also found in the folder “C1168 Tranche 5” on N: Drive. A USB with summary sheets which are also found in the folder “Tranche 5” on G: Drive. HAS BEEN CATALOGUED but the CDs have not been given BL catalogue codes. There is also a cheat sheet explaining some stranger donations.

6 Rogue CDs – Definitely from Tranche 5 but these have bee labelled with their BL catalogue code.

Tranche 12

FIVE INTERVIEWS IN TRANCHE 12 ARE ALSO IN TRANCHE 4 IN THE FOLDER “WORKHOUSE”

The names are: Curtis & Freeman, Pointon, Smith S, Bush, Green

Property: The Workhouse, Southwell

Harddrive – OneDrive dump same as in the folder “C1168 Tranche 12” [N: Drive]

Box 1 of mini discs – Five interview which have been digitised and can be found in “OneDrive_3_25-09-2020” in N: Drive. Interview with Brain Kay which does have a summary in N: Drive but no audio file. And an interview with Margaret Adkin which does not have any material on N: Drive. One disc has no label, one has “interview (2)” as label and the final one is a test disc.

Box 2 of mini discs – One mini disc possibly labeled Touley, Law (handwriting is hard to read). And two labeled “Wendy Ryan ?” Note: Wendy Ryan’s interview is not in N: Drive.

9 CDs – also found on N: Drive. One is labeled Barker but there are two Barker in the spreadsheet

25 cassettes – Cassette not ripped from mini discs. One is labeled Holmes but there are two people called Holmes in the spreadsheet.

20 cassettes ripped from 13 mini discs

Tranche 10

Property: Bateman’s, Mottisfont, Mottistone, Stockbridge

6 cassettes of 3 interviews

A memory stick which is labeled Tranche 4 but is not Tranche 4 or any other Tranche

NT property recommendations for PhD placement

Hannah James Louwers

21 June 2023

Questions to ask

Would you have good access to the local people who might know of the interviewees?

Are you looking to show how NT should do oral history projects or how they should handle collections of older recordings stuck on shelves?

Properties

Alderley Edge Landscape

Location: Cheshire

Notes on property: They only have two full time rangers and it is a landscape property, not a house so it is unlikely they will have a collections team.

No. of recordings: 80

Main interviewers: John Ecclestone

Date of recordings: Late 1990s – early 2000s

Copyright statues: 17 recordings have copyright and there are a handful of orphan works. Copyright is confusing here, there seems to be focus on getting copyright from the interviewers.

Notes on recordings: Big project in collaboration with the Manchester Museum. There are also several lectures. It also has a website: Alderley Edge Landscape Project (derbyscc.org.uk)

Hannah’s recommendation: ⭐ ⭐ It is one of the biggest projects but because the property is unlikely to have a collections team, you will have no one to champion the work.

Attingham Park

Location: Shropshire

Notes on property: An 18th-century estate. Property ‘Trust’ property. BIG!

No. of recordings: 43

Main interviewers: Edward Payne, Michael Ford, John Ecclestone

Date of recordings: 1960s – 2000s

Copyright status: Half copyright, half not.

Notes on recordings: These recordings came in tranche 5, which was all CDs, many copied from original tapes. Note that some recordings in tranche 5 might be duplicates of recordings in tranche 1.

Hannah’s recommendation: ⭐ ⭐⭐ A lot of recordings taking over a very long period of time. I imagine this might be a difficult one.

Basildon Park

Location: Berkshire

Notes on property: Big 18-century estate. Very ‘Trust’

No. of recordings: 12

Main interviewers: Mary Turton

Date of recordings: 1980s – 2000s

Copyright status: Half have copyright, half does not

Notes on recordings: Many different interviewers

Hannah’s recommendation: ⭐ ⭐ ⭐ ⭐⭐ A small set of recording which might be more manageable for a three month project.

Biddulph Grange Gardens

Location: Straffordshire

Notes on property: It is a garden, so they are unlikely to have collection staff.

No. of recordings: 48

Main interviewers: John Ecclestone, Michael Ford, Bill Malecki

Date of recordings: 1980s – 2000s

Copyright status: 5 recordings have copyright and there are some orphan works

Notes on recordings: Bill Malecki is also the garden and was interviewed

Hannah’s recommendation: ⭐ ⭐ ⭐ This collection might be too big for the three month placement and I am not sure of the staff set up on site. You are likely to have to work with the regional curator.

Blicking Hall

Location: Norfolk

Notes on property: Jacobean mansion with big garden.

No. of recordings: 18

Main interviewer: Nick Ross

Date of recordings: 1980s, and one in 1990

Copyright status: One has copyright

Notes on recordings: Nick Ross did all his recordings in 1986-1987. There is one recording of 11th Marquis of Lothian which was recorded during WW2.

Hannah’s recommendation: ⭐ ⭐ ⭐ ⭐ Small collection but recorded a long time ago which might make things difficult.

Calke Abbey

Location: Derbyshire

Notes on property: Home and estate.

No. of recordings: 41

Main interviewers: Kerry Usher

Date of recordings: 1980s – 1990s (most are unknown)

Copyright status: Many have no accession form

Notes on recordings: Only five recordings were not recorded by Kerry Usher

Hannah’s recommendation: ⭐ ⭐ ⭐ ⭐ This one could be very easy if the property just forgot to give the copyright forms or it will be very difficult.

Clent Hills

Location: Worcestershire

Notes on property: It is a walking route and not an estate, so will not have a collection team

No. of recordings: 11

Main interviewers: Tamsin Mosse

Date of recordings: 2009-2010

Copyright status: One recording has copyright

Notes on recordings: These were recorded onto CDs from a Flash Memory Card by John Ecclestone in 2010

Hannah’s recommendation: ⭐ ⭐ ⭐ ⭐ A more recent one which might make things easier and make up for the fact it is a walking route and not an estate

Clumber Park

Location: Nottinghamshire

Notes on property: Park with a walled garden, a chapel, and ornamental bridge.

No. of recordings: 14

Main interviewers: Leah Lawman, Alistair McDougal

Date of recordings: 1990-91

Copyright status: No copyright at all

Notes on recordings: Classic project run in the early 1990s by the looks of it.

Hannah’s recommendation: ⭐⭐⭐ Could be a good case study because it is clearly a case of an oral history project, which is how many of the NT oral histories will be collected

Coughton Court

Location: Warwickshire

Notes on property: A tudor house in Warwickshire. Classic NT and probably very popular

No. of recordings: 13

Main interviewers: Michael Ford

Date of recordings: 1970s -1980s

Copyright status: One recording has copyright

Notes on recordings: This is a classic early oral history project for NT. Robin Bryer and Michael Ford did some of the earliest recordings for the Trust. Also this one is likely to have duplicates in tranche 5, because tranche 5 consists of CDs made from cassettes. I suspect BL might have some of the original cassettes.

Hannah’s recommendation: ⭐ ⭐ ⭐ ⭐⭐ It is a classic NT oral history project and will be a good example of how to handle material from project long gone by rather than be a good example of how to do contemporary projects.

Dudmaston

Location: Shropshire

Notes on property: Country house still lived in

No. of recordings: 14

Main interviewers: Bill Gatter, Jeremy Milln, Sarah Kay

Date of recordings: 1980s-2010s

Copyright status: No copyright

Notes on recordings: John Ecclestone worked as sound recordings on most interviews. Originally recorded on mini disc but the BL only has the CDS from tranche 5. (Yes, someone was recoding on mini disc in 2012).

Hannah’s recommendation: ⭐ ⭐ ⭐ ⭐⭐ It is a small collection recorded over a wide period of time and none have copyright.

Dunham Massey

Location: Cheshire

Notes on property: Garden, deer park, and a house

No. of recordings: 70

Main interviewers: Peter Lee, James Rothwell

Date of recordings: 1980s – 1990s

Copyright status: One big chunk does have copyright, another chuck have no accession forms, and there are some that have the reuse forms which do not include the word copyright.

Notes on recordings: Many different interviewers.

Hannah’s recommendation: ⭐ ⭐ ⭐⭐ Big collection with everything present but it might be too big for a three month project

Hardwick Hall

Location: Derbyshire

Notes on property: Classic ‘Trust’

No. of recordings: 25

Main interviewers: Tim Whittaker, Alistair McDougal

Date of recordings: 1980s-1990s

Copyright status: No copyright

Notes on recordings: Possibly two different oral history projects one in the 1980s and one in the 1990s

Hannah’s recommendation: ⭐ ⭐ ⭐ ⭐⭐ A classic Trust property with an average amount of recordings.

Monk’s House

Location: East Sussex

Notes on property: Leonard and Virginia Woolf’s 16th-century country retreat. Smaller property

No. of recordings: 12

Main interviewers: Patricia Tate, Malcolm Billings

Date of recordings: 1990s

Copyright status: No copyright

Notes on recordings: Patricia Tate is likely to have died or be over 100 years old. There are also a lot of radio recordings for this property

Hannah’s recommendation: ⭐ ⭐ ⭐ ⭐⭐ A smaller property and collection might be more manageable

Osterley Park

Location: London

Notes on property: House and parkland

No. of recordings: 18

Main interviewers: Jean Price, Gwyneth Learner, Lucy Tusa

Date of recordings: 1989 – 2000s

Copyright status: No copyright

Notes on recordings: Jean Price recorded in 1989, Gwyneth Learner in the 1990s and Lucy Tusa in the 2000s

Hannah’s recommendation: ⭐ ⭐ ⭐ ⭐⭐ A London based property might mean you are able to go and rummage around their cupboards for copyright forms. Also an average sized collection made of three bouts of recordings.

Powis Castle

Location: Powys, Wales

Notes on property: Medieval Castle (not very Trust)

No. of recordings: 21

Main interviewers: Michael Wynne Griffith

Dates of recordings: UNKNOWN

Copyright status: No copyright

Notes on recordings: A very messy collection. Many of the interviews do not have an interviewer noted in the catalogue

Hannah’s recommendation: ⭐ ⭐ A challenge

West Wycombe Village and Hill

Location: Buckinghamshire

Notes on property: Mansion and parkland

No. of recordings: 19

Main interviewers: Olga Macdonald, Alison and Peter Gieler

Dates of recordings: 1990s – 2010s

Copyright status: The more recent recordings one have copyright. The older ones recorded by Olga do not.

Notes on recordings: Olga was later interviewed in the more recent project. I suspect the more recent project was run by volunteers.

Hannah’s recommendation: ⭐ ⭐⭐⭐ The first project does not have copyright sorted but they clearly have sorted everything out for their more recent project. They might be easy to work with if they are familiar with oral history already.

To date I have collected ten oral history interviews with a wide range of people associated with Seaton Delaval Hall, from former residents to National Trust staff and volunteers. Overall, the experience has been positive for both myself and those I have interviewed. I have enjoyed listening to their stories and many have told me after the interview how much they enjoyed the experience. It is important to note I am recording under Newcastle University and not the National Trust. This means I need to follow the university’s ethics and data protection policies. However, during my three-month placement at Seaton Delaval Hall and my efforts to get the recordings archived, I developed a better understanding how recording oral history within the National Trust works.

If you type oral history into Acorn you get “the guide to setting up an oral history project.” Although sadly many of the links to other Trust oral history projects are dead-links, the guide gives a good foundation to recording oral history. The emphasis of working with The British Library and getting training from the Oral History Society which can be paid for by the Sir Laurie Magnus Bursary is great. I have come across many oral history projects where archiving is very much treated as an afterthought, so it is refreshing to see how the guide encourages working with an archivist throughout an oral history project. However, both the guide and the current permissions and copyright assignment form, which is to be used for archiving the recordings at the British Library, are not completely up to date with regards to data protection and the copyright assignment. There is little to no mention of GDPR and the copyright assignment looks a little too simple if compared to what copyright, data protection and licensing experts, Naomi Corn Associates, currently advise.

It is also important to point out that in the guide there is no mention of the ethical issues you need to consider when recording oral history, only a small paragraph on what to do in case the interviewee gets upset. Because I am recording oral histories via Newcastle University I had to go through thorough ethical approval. There is no such process within the National Trust.

Another slightly out of date element is the storing of the oral history recordings before they are archived. The guide focuses on an electronic cascading file system, which is fine. But it does not discuss the devices where these files need to be stored and I am pretty confident that the way the National Trust stores its files has clearly changed since the writing of this guide. I contacted the data protection office and they informed me that an oral history recording and its accompanying metadata needs to be stored on SharePoint for data protection reasons. This seems completely logical, only I was also informed by IT that they would prefer it if people did not have large WAV files on SharePoint because this interferes with the Trust’s carbon neutrality aims. I would also like to note that the archivists I have talked to emphasise that a digital file only exists if it is stored in three different places with at least one of them not being cloud based. There is therefore a slight conflict between data protection and IT, although I was later offered to upload my WAV files to the Seaton Delaval Hall SharePoint, after I mentioned this issue to a member of staff.

In addition to dissecting the Trust’s guide to oral history I have become familiar with the British Library’s cataloguing system – cadensa. It is definitely not the most user-friendly interface and the software company that developed it seems to no longer support cadense, which is slightly worrying. The National Trust audio collection at the British Library is their biggest collection with over 1000 entries but access to these recordings is limited due to the cadensa software. From the contact I have had with the British Library they are aware of their limitations and understand they might not be able to offer the best access to archived recordings. They are after all also working with limited resources.

What I believe I am able to concluded from my experience doing oral history recordings on a National Trust site, is that the foundations are there but they just need updating. By bringing together oral historians, IT support, the data protection office, archivists, and copyright experts one could easily update the guidance to make the process safer and more ethical.

This was not a very good paper. I was very busy and I did not put my whole heart in it, which is always a shame. But a learning moment to remember to plan these things better

Google Gemini Summary of OHD_PRS_0118 - Connecting with history through our screen

[generated 06 / 01 / 2025]

Challenges with Existing Digital Archives: You effectively critique current digital archives, highlighting their limitations in capturing the serendipity and emotional connection often associated with physical archives. Issues such as clunky interfaces, limited search functionality, and the loss of contextual information are identified.

The "Archive-Robot" Metaphor: This is a novel and insightful perspective. By framing digital archives as "archive-robots" still under development, you emphasize the need for ongoing refinement and improvement. It shifts the focus from simply replicating physical archives to exploring new possibilities for digital interaction and engagement.

The Importance of Human Connection: You emphasize the importance of human interaction and the emotional connection to physical archives. You highlight the limitations of purely digital experiences and the need to consider the social and cultural contexts of archival research.

Ethical Considerations: You raise important ethical concerns regarding data privacy, digital inequality, and the environmental impact of digital technologies.

A Call for Innovation: You advocate for a more human-centered approach to digital archives, emphasizing the need for creativity, collaboration, and a willingness to experiment with new technologies and methodologies.

Key takeaways for your PhD research:

Focus on User Experience: Design digital tools that are intuitive, user-friendly, and enhance rather than hinder the research experience.

Embrace Collaboration: Foster close collaboration between oral historians, archivists, technologists, and community members throughout the design and development process.

Prioritize Sustainability: Consider the long-term sustainability of digital technologies, including maintenance, data preservation, and environmental impact.

Explore Innovative Approaches: Experiment with new technologies and methodologies, such as AI and machine learning, while also recognizing the limitations of technology and the importance of human interaction.

Overall, this presentation demonstrates a strong understanding of the challenges and opportunities presented by the intersection of oral history, technology, and heritage management. Your insightful observations and critical thinking will undoubtedly be valuable assets as you embark on this exciting research journey.

Since the start of my PhD in January there are two things I have observed when people talk about archives during COVID.

I, too, hold these opinions. I have recently started digging through the National Trust’s oral history archive which is housed at the British Library and it has not been the most relaxing affair. Every time I clicked on an entry and then wanted to go back to my search results I would have to refresh my page and if I accidentally clicked on any of the names that were hyperlinked in the entry pages I would lose my place in the archive and have to go back to the start. I also have very little experience of actually working in an oral history archive so really need to visit a brick and mortar archive that houses oral history. The only information I do have on listening to oral history in a brick and mortar archive comes from my friend who told me in horror how they had given a CD player and a broken set of headphones.

What I am going to do for this presentation is dissect these two observations and explore how I can reframe these in order to use them in my work for my PhD.

Point 1!

Let us start with the digital archives that so many of us have had to rely on over the last year. Digital archives exist because they are following the bigger trend of moving our lives online. But this move from brick and mortar to digital is about a literal as it can get. When I was going through the National Trust’s oral history archive it felt as if the British Library took the index cards that accompanied the recordings and just transcribe them into a webpage. They moved the collection online without thinking about how this new realm could enhance the experience of archive. Other than the fact that this makes going through the archive a bit frustrating and boring you also lose that serendipity that everyone always talks about when they are in brick and mortar archives: the scribble in the margins, the note lost in the pages of a book. These two things: the loss of serendipity and the direct translation is why I believe people are complaining.

So how do we solve this? To start with I suggest a reframing of what we think a digital archive is. As I previously mentioned a digital archive is not the digital equivalent of a brick and mortar archive because we lose that serendipity that we love so much. So what if we view the digital archive as a tool to access the information in the brick and mortar archive. Our computers, browsers and webpages then become the tools that grant us access to the archive, which is a role normally held by archivists. They are the people who usually accompany us in our journey through the brick and mortar archive. But our computers, browsers and webpages are not the same as a fully trained archivist. An archivist is a human who is capable of complex and creative thought. They can solve problems and navigate around barriers, while a computer is only as creative as its database and code allows it to be. So we could view digital archives as a digital alternative to archivists but I believe this would still cause frustration, because within this framing we are still comparing the new digital archives to the old brick and mortar archives and in this fight the brick and mortar archives have the creative upper hand (for now.)

So I would like to propose another way of framing our digital archives. A couple of weeks ago I attended a seminar on AI. During the seminar, Professor Irina Shklovski from the University of Copenhagen presented a paper called AI as Relational Infrastructure. She discussed how the way we view AI is all wrong. We view AI as a tool we can used but Shklovski suggested that we should view it as a relationship, an exchange of skills and knowledge. So I translated this principle onto my work in the National Trust’s oral history archive. This translation made me view my computer, the browser and this British Library portal as an archive-robot that was trying to help me navigate the messiness of the brick and mortar archive on the other side of my screen. However this archive-robot is very new to the archive; we need to remember that digital archives are the new kids on the block and these archive-robots do not know the ways of the archive yet. The way that I currently picture this relationship is as follows. Here we have our archive-robot who has just started their new job at the archive, they do not really know what they are doing, they might have even lied a bit on the CV. Along come a lot of random people who start handing all their documents, notes, and other bits and bobs over to the archive-robot, who and I cannot stress this enough has no idea what they are doing, and expects them to just sort everything out. This is a rather tall order as we already know that archive-robots cannot think as creatively as a human-archivist – yet. What we need to do now as a community that uses these archives is train these new kids in archiving because in the end they will help us in our research.

I know this sounds like I am advocating robot rights. Maybe I am a bit but what I really trying to say is that instead of viewing digital archives as the digital equivalent of brick and mortar archives, or viewing them as tools to access those archives, you can view them as an archive-robot who is trying to adapt to this new world as much as you are. It might sound like a silly idea but I can tell you from experience it eases the frustration a bit. And most importantly if we view our digital archives like this we put ourselves into a mindset that allows us to seek progress and development in our digital archives and not just settle for this rather crude translation of brick and archives. Digital archives are still in development and I think that if we see them more like archive-robots in training then maybe we can help them help us.

Point 2!

People miss brick and mortar archives. Other than the fact that we don’t really like digital archives right now, I think there is something deeply emotional about people’s desire to reenter brick and mortar archives. Even though we might have access to certain documents online, people still want to be near the physical document. Just like how people travel to see the Mona Lisa despite the fact that everyone knows what the Mona Lisa looks like. This feeling, this desire, this need to be in the physical space I also see in my mother, who because of the pandemic has not been able to travel to her motherland the Netherlands for nearly a year now. Just like the archive-robots allow us to connect to the brick and mortar archives, my mother has been able to connect to her homeland via her devices be that FaceTime with her sister, watching dutch tv, reading dutch newspapers or listening to dutch radio. But we know it is not the same as physically being there. She wants to connect to the land. She wants to be in that physical environment. And I think this feeling is very similar to people missing brick and mortar archives as if the archive is their motherland.

I think it is necessary to understand the importance of this connection when it comes to research. Connecting with your subject of your research in an emotional way can help one be more responsible in how we handle our archival material. This is especially important in cases where the archival material is from someone who is still alive or has close living relatives, which is something that is very common with oral history. When we use our digital devices to access archival material or in fact do anything that involves interacting with humans dead or alive online we have something I am going to call “digital distance”.

Through our screens we reduce humans to a handful of pixels, a username and 240 character statements. This is digital distance and the reason why some people do or say bad things because that person to them is not fully human because the way they are presented on our screens is not fully human – you cannot look them in the eye. Now obviously you cannot look the creators of archival material in the eye because most likely they are dead. But their humanity is present in the archives in their bad handwriting, spelling mistakes and doodles. Physically being with the documents, imagining what they smelt, felt and saw when they were creating this document makes us connect on an emotional level. It reminds you that these are not just bits of isolated evidence but actually are part of a wider portrait of someone’s life. You become invested in this ghost type thing and the only way to truly feel their presence is by being in the brick and mortar archive.

This feeling of closeness that people want to have with the Mona Lisa and feeling of belonging that people have with their motherland they can be found in people desire to go back into brick and mortar archives. It is a connection that is strange and maybe nothing completely logical but very human. I think by reframing this observation as the archive as motherland highlights the importance of the physical in archiving. It is a physical activity and the fact that it is physical plays an important role in responsible researching.

How does this help me?

For my PhD I have been challenge with building an oral history archive-esque thing at the National Trust property Seaton Delaval Hall in Northumberland.

So, how can this reframing of observations into the archive-robot and the archive-motherland help me build an archive?

Reframe 1

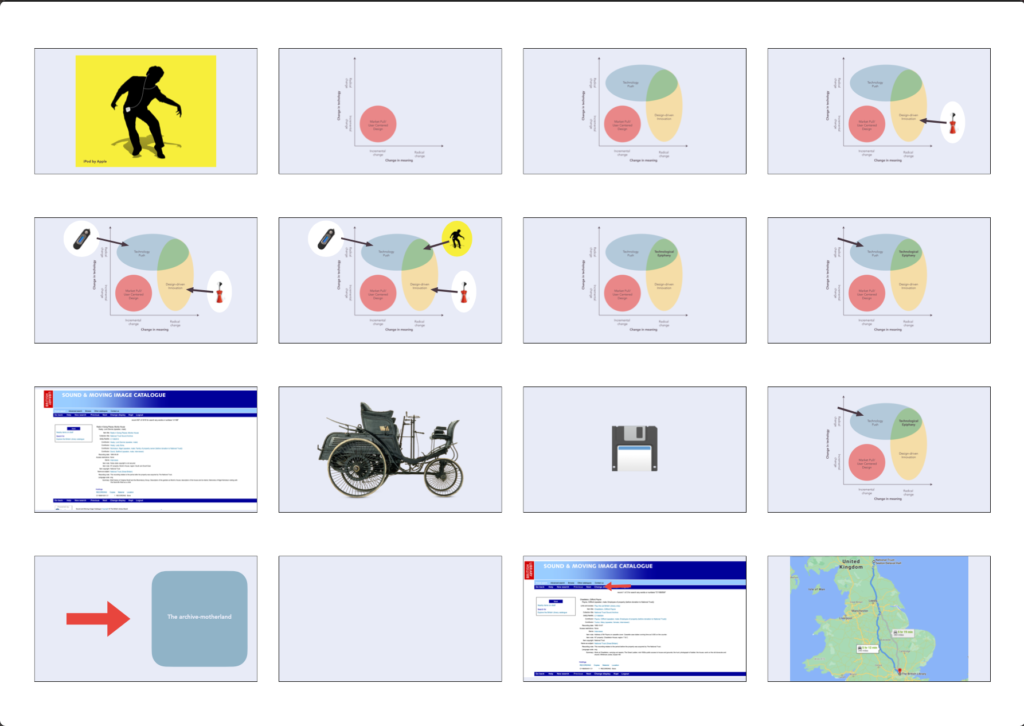

As I said previously by reframing the frustrations of the digital archive into the naive archive-robot we put ourselves into a position where we want actively want change. We are thinking about what the archive-robot might look like when they grow up. What this reframing allows me to do is start thinking in terms of design-driven innovation. Design-driven innovation is a term used by the design scholar Roberto Verganti in a book by the same name. The idea behind design-driven innovation is seeking to change the meaning of an object or system. For example, corkscrews are there to open my wine but this corkscrew by Alessi “dances” for you and plays on you inner child. Similarly portable music players allowed you to listen to music on the move, but the iPod allowed you to cheaply buy songs from iTunes and then curate them into your own personal soundtrack.

Here we have two axis: change in technology and a change in meaning both have a scale from incremental to radical change. In the corner we have market pull/user-centered design. Here we have the bubble design-driven innovation, where see radical change in meaning and the bubble technological push where there is radical change in technology. In this yellow part where there is a radical change in meaning but not in technology we find designs like Alessi’s corkscrew. In this blue section we find technologies like the first mp3 player, which was a significant technological upgrade from portable cassette and cd players. Now in this green part we find the iPod. This green part is what Verganti refers to as a technological epiphany.

Currently our digital archives and archive-robots live here in the blue section where there is an upgrade in technology but not in meaning. As I said using the British Library does feel like they uploaded the index cards. By the way, this is not a just people being silly, human kind always does this when there is a change in technology. The first cars looked like carriages and our save button looks like a floppy disc. We don’t like radical change so we keep the meaning and symbols. But for my PhD I want to do what Apple did in 2001 and also achieve a technological epiphany. I want to upgrade the archive-robot because I think this is the perfect opportunity to do so when everyone is using digital-archives so much and complaining about them.

Reframe 2

So how will I use this idea of the archive-motherland in my work. As I briefly mention before oral history often deals with people who are still alive so looking after their archival material responsibly is imperative. That is why I do not think it is too much to ask that if you want to take information from the community you should probably think about becoming part of that community. And the only way to do that is to physically go there and look the people in the face. This is not a new idea there are many archives that only allow you to access the oral history recordings if you are in the building where they are stored. This is the case with the National Trust’s oral history archive which you can only listen to if you are in the British Library. Now I think you might be able to predict what my problem with this is. The British Library is in London and quite some miles away from Seaton Delaval Hall in Northumberland. So if I want to keep this principle of connecting to history through physical space I might have to very politely ask the British Library if they could maybe bend the rules for me.

Conclusion!

I think that what I am trying to get at here is that through these observations and reframing I think I can say that connecting with history is a deeply human process. And the way we do it and the way it is changing because of technology and the pandemic is nothing new to human kind. I think that while we do pursue these new technologies we also need to remember that emotional connection we have within the brick and mortar archives. I do not know for sure what archives will look like in a years time but a lot of it with have started now during the pandemic.

I really want to end on a quick note that I think it is really important to remember that the internet and the servers that the internet is store on use up a truly insane amount of energy and are very bad for the environment and the majority is own by amazon, which is actually a terrifying idea when you think about it.