Tag Archives: Collaboration

OHD_WKS_0297 SDH OH workshop

OHD_RPT_0296 SDH oral history strategy

Seaton Delaval Hall Oral History Strategy

V1

Hannah James Louwerse

1. Aim

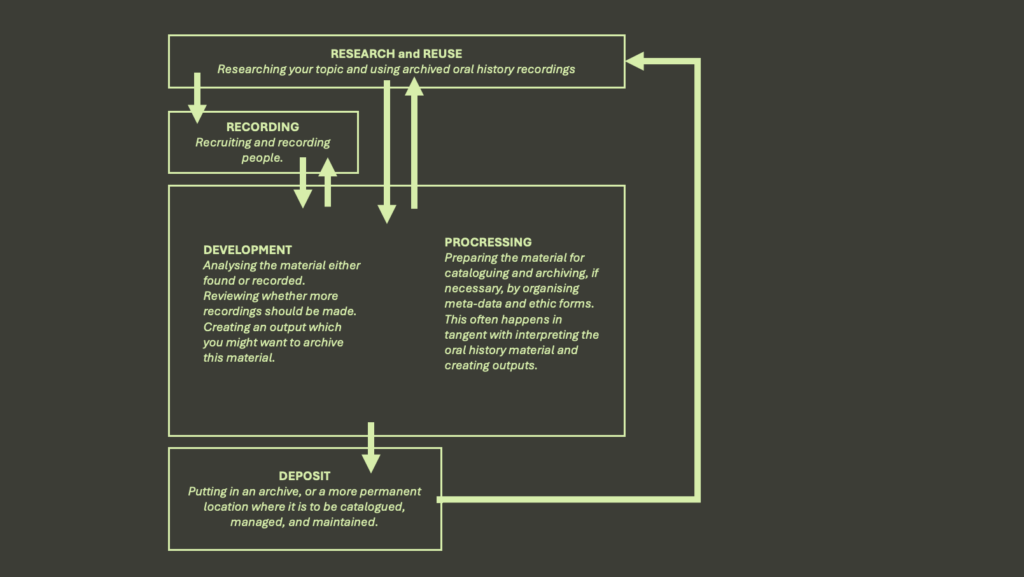

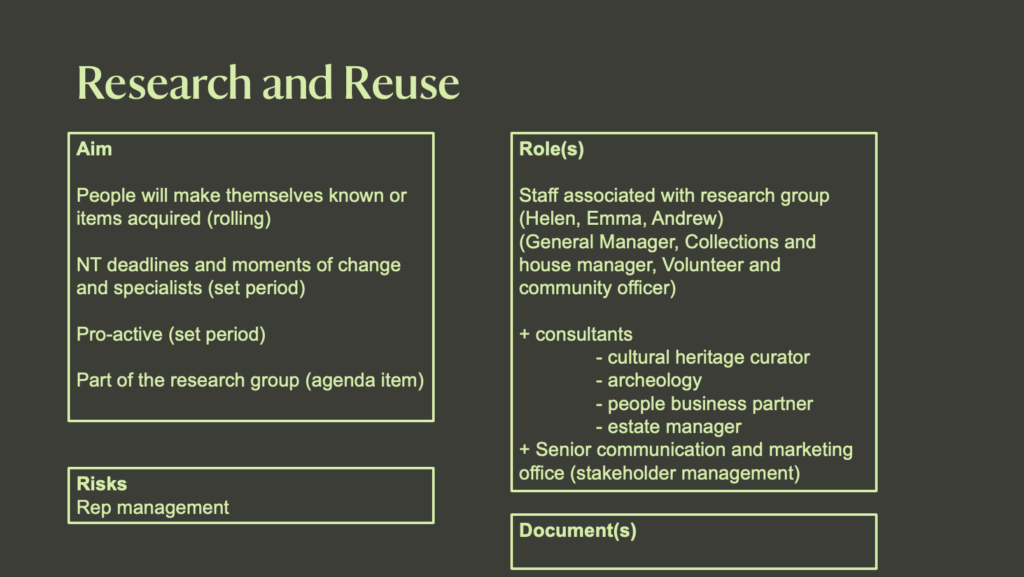

The overall aim of the strategy is to embed oral history practices into the Hall’s existing research activities to create an ongoing process of collecting, interpreting, and sharing oral histories.

2. Roles

2.1 Core Oral History Team

The core oral history team consists of the General Manager, the Collections and House Manager, and the Volunteer and Community Officer. These members of staff already lead and support the volunteer Research Group. Their added responsibilities will encompass:

- setting up designated oral history training for volunteers and staff;

- organising the recording of new oral histories;

- recruiting volunteers for the recording and processing of oral histories;

- offering emotional support and guidance to the interviewers and transcribers.

In addition, this group will make up the reviewing team in charge of checking sensitive content in both the archived and newly recorded oral histories. They will also lead the oral history review which will take place annually during a Research Group meeting.

2.2 Supporting Site Staff

Although the Senior Communication and Marketing Officer is not part of the core oral history team, their contribution is essential for the successful implementation of the strategy. They will advise the core oral history team in matters related to the Hall’s reputation and data protection issues.

2.3 Supporting regional NT staff

Identifying and recruiting candidates for oral history interviews will require drawing on the expertise of regional National Trust staff, such as people business partners, estate managers and cultural heritage curators in, for example, archaeology.

2.4 Volunteers

Conducting interviews, managing data, and transcribing or summarising new oral histories will to a large extent be executed by NT volunteers. Equally, they will play a vital role in the researching of the archived oral history recordings.

3. Collecting oral histories

3.1 Scope and Focus

There are two forms of oral history which the Hall is aiming to collect:

- institutional memory

- histories of the cultural fabric of the Hall and the surrounding area

The recording accounts on the maintenance, restoration, and management of the site will help the Hall build an institutional memory. Collecting this information will create a collection of recordings which demonstrate the wide and diverse range of work done to preserve the site, its collection, and its history. It also avoids the loss of knowledge that occurs when an individual leaves the Hall. Histories of Seaton Delaval Hall’s cultural fabric will include recording information and stories about the collection, the hall, the gardens, and the surrounding area etc.

3.2 Pro-active Collection

The oral history is to be collected in a pro-active fashion, fully into the Hall’s knowledge gathering practices. Moments for potential collection are, for example, when a new item is acquired; as part of a research project; after restoration work; or when a significant person visits the Hall. More moments of collection will emerge as oral history gathering becomes a common practice on site.

4. Recording and processing oral histories

4.1 Training

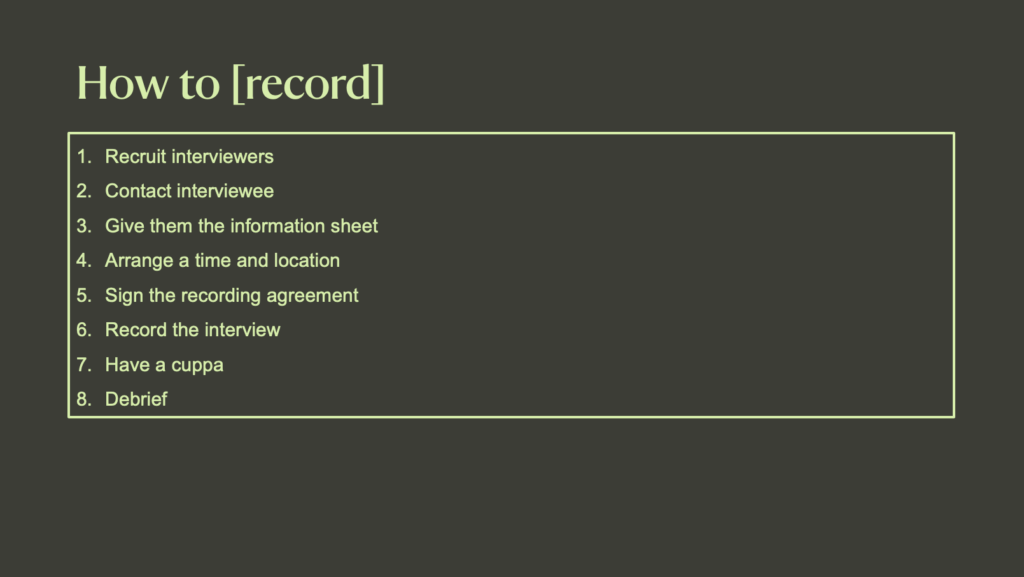

A handful of staff and volunteers can be trained in oral history interview techniques, processing the recordings, and analysing the oral history material. Training sessions should be arranged at regular intervals, e.g., every three years. An analysis of training needs and requirements will be reviewed annually during a Research Group meeting. The training can be done through the oral history society or through Northumberland Archives.

4.2 Interim Storage

An interim storage solution needs to be arranged with the IT Department and Data Protection Office. Both have specific requirements for digital devices and Microsoft SharePoint.[1] In addition, there are restrictions on what external devices can and cannot be connected to Trust computers. Until a solution has been arranged, it is best to follow two main principles of digital storage: keep the recordings in three different locations and ensure those locations follow data protection law.

4.2.1 List of stored material

All material listed here contains personal information.

- Audio files (a WAV copy and a MP3 copy)

- Interviewee data sheets

- Recording permission forms

- Copyright and reuse forms

- Summaries and/or transcripts

- The Seaton Delaval Hall oral history catalogue

4.3 Ethics

4.3.1 Paperwork

There are two ethics forms necessary to collect and archive an oral history recording:

- a Recording Permission Form

- a Copyright and Reuse Form

The Permission Form must be signed before the recording device is switched on. The Copyright and Reuse Form is signed after the interviewee has read the transcript/summary of their recording or has listening back to the audio. The Copyright and Reuse Form allows the interviewee to close all or part of the recording for a set amount of time. Note that both forms contain personal information and therefore need to be stored in adherence with data protection law.

4.3.2 Sensitivity checks

Sensitivity checks are the responsibility of the core oral history team. They will read or listen to the oral histories and assess whether there is any sensitive content. Sensitive content comes in two forms:

- information the interviewee might not want out in the public domain

- information that could upset the listener of the recording

If the former is flagged by the core oral history team because they believe the interviewee might not want to share particularly information publicly, they should mention this to the interviewee before they sign the Copyright and Reuse Form. This may result in the interviewee wanting to close a particular section of the recording. If the team finds material which fits the latter, any sensitivity warnings should be added to the index.

4.4 Indexing

The spreadsheet created for indexing the Hall’s oral history recordings allows for easy tracking of progress and searching. It is also compatible with the British Library’s method of cataloguing in case the recordings are at some point donated to the British Library. The index contains personal information and therefore needs to be stored according to data protection law.

4.5 Transcripts and Summaries

The strategic aim is to create both a transcript and a summary for each oral history recording. Transcripts are essential if the audio file is lost or is corrupted. Interview summaries allow for content to be described in more searchable terms.

5. Archiving

Oral history recordings can be archived at Northumberland Archives. However, backup copies should be kept at the Hall in case the recording is also archived at the British Library. This is especially crucial since Northumberland Archives only excepts MP3 files and the British Library requires WAV files.

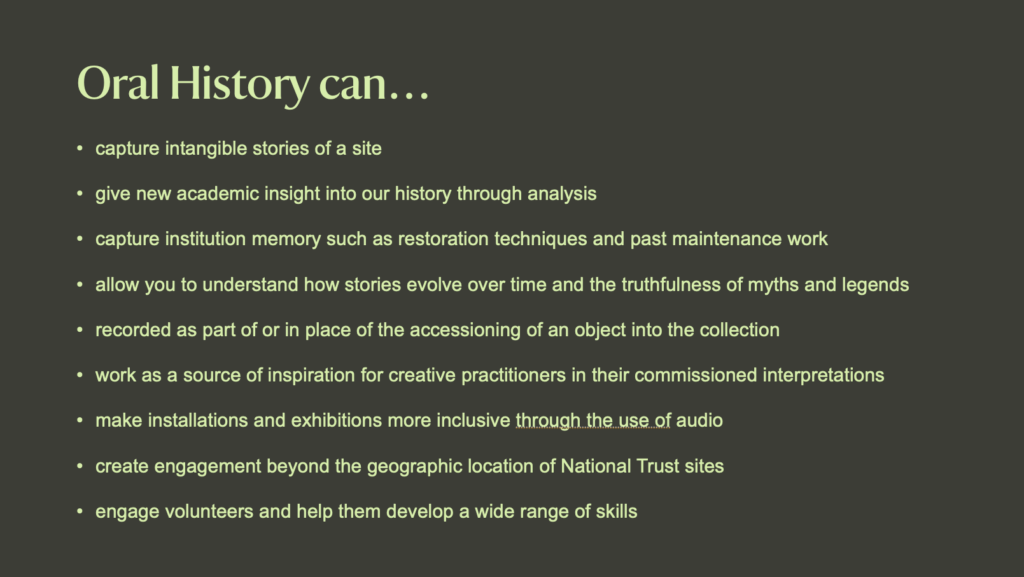

6. Reusing oral histories

In connection with the Hall and the collection, oral history can be used in interpretations and exhibitions. In addition, new staff or contractors can access the hall’s institutional memory and learn about their predecessors and their work by listening to the stories shared. The overall objective is for oral history to be a fully integrated and accessible resource, equally available for consultation as any item in the collection.

[1] For example, the IT department does not want WAV files to be put on SharePoint because they are very large, while the Data Protection Office requires all personal data to be stored on SharePoint.

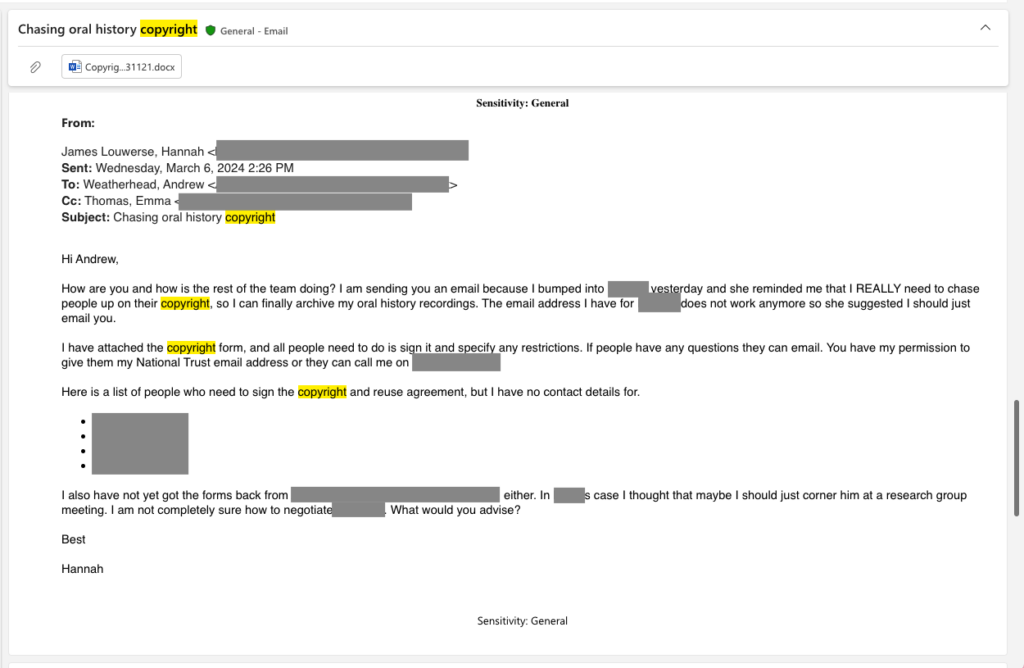

OHD_SSH_0294 Screenshot of email

OHD_PRS_0265 Reusing oral history in GLAM: a wicked problem

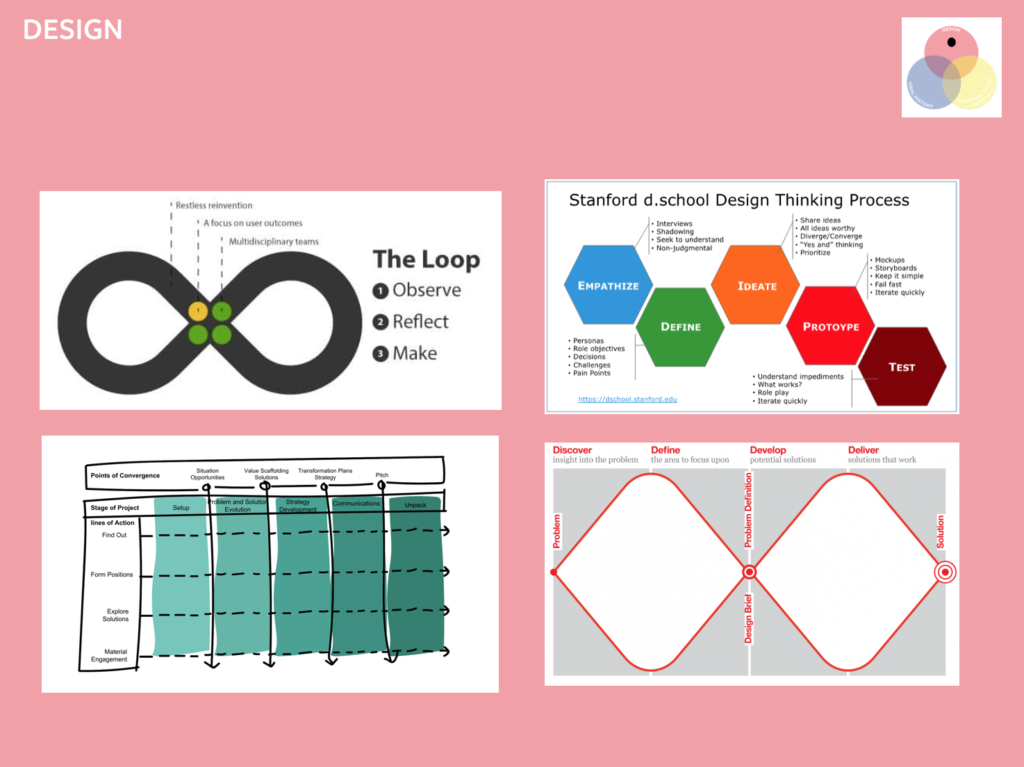

My PhD or CDA, collaborative doctoral award is about reusing oral history recordings within GLAM, galleries, libraries, archives, and museums. I am using the National Trust property Seaton Delaval Hall, as a case study. Now for context my background is in Art and Design. I did Fine Art at undergrad and then moved into design, specifically innovation and system design. And so when it comes to the infamous issue of reusing oral histories I approach it from the perspective of a designer. This has led me to frame the issue as a “wicked problem”. The term “Wicked problem” comes from a paper titled, Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning, written by a Professor of the Science of Design, Horst Rittel and a Professor of City Planning Melvin Webber in 1973. And the term has been adopted by innovators and designers because this paper is about problem solving and the act of design is basically problem solving. In the paper Rittel and Webber specifically discuss two types of problem solving: “tame and benign” problems and “wicked problems”. Tame, benign or scientific problems are simple. They are easy to define and have one simple solution. It is a very linear process: define problem, solve problem. A wicked problem is exactly the opposite. They are extremely difficult to define and coming up with one simple solution is close to impossible. And the process of solving a wicked problem is not linear at all. Defining the problem and creating solutions often happen at the same time in a kind of back forth manner. You make an initial definition of your problem and create a solution to that problem and then the testing of a solution reveals another part of the problem. So you go back to your problem definition and tweak it, and then think of another solution and it repeats. In fact, as Rittel and Webber write this process could go on forever since a wicked problem will forever keep evolving as the world changes. You can therefore never truly solve a wicked problem but only pick various interim solutions which are not perfect but will cause the least damage. And to keep creating these interim solutions you need collaboration because a single person could not possibly understand all the evolutions in the wicked problem, all the different angles, all the different stakeholders.

Therefore my project is a Collaborative Doctoral Award for a really good reason. I have benefitted greatly from being in collaboration with the National Trust because I got access to a huge variety of people who I could work with in order to build a better understanding of the problem definition and any potential solutions. And over the nearly three years I have been working on this project I have been able to expand the definition of the oral history reuse in GLAM problem. It is extremely complicated, and the specifics of my case study will not be the same as all GLAM institutions. As trait seven of wicked problem goes “every wicked problem is essentially unique”. But I have found five recurring areas of wickedness, which most GLAM institutions will have to deal with when tackling the reuse of oral history recordings: technology, labour (specially maintenance labour), money, ethics and law, and value. In order for an organisation to start understanding the wicked problem of oral history reuse and start creating solution, there needs to be a collaboration between the people who work within these five areas. Within each unique institution there will definitely be other areas and other people that need to be brought to the table but it is these five areas and the people who work in them which make up the foundation of solving the wicked problem of oral history reuse.

I am going to start with technology because this is the area which often hogs all the attention, which is not surprising, we like the technological fix, it’s sci-fi, it’s the future, it’s a bit magic. But its magic is an illusion, as Willem Schneider acknowledges in his reflection on the oral history reuse technology Project Jukebox[1]. Technology on its own will not solve the wicked problem of oral history reuse. Obsolescence has be built into technology in a near aggressive way. So while you can recruit a software engineer at the start your project to develop your technology, you are going to need someone who is able to maintain the technology when obsolescence kicks in. The area of technology is therefore completely intertwined with the area of labour, specifically maintenance labour. Maintaining a technology is not easy and the more complex a technology, the harder it is the maintain, and the more specialised person you need to hire to maintain it.

So when we think about the technology we are going to use to tackle our wicked problem, we need to always be thinking about the labour needed to maintain it. We need to collaborate with those who will maintain it and not be seduced by magic of complex technology. Because while we now have complex AI technology like ChatGPT, I can tell you from experience, and I am sure many of you can relate, in the National Trust you are using a landline to organise interview dates and posting transcripts and consent forms by snail mail. As the historian David Edgerton writes in his book The Shock of the old we should not measure technology through innovations but rather use. In which case Excel and Word are still king of the technologies.

So the technology used to help create a solution to the wicked problem of oral history reuse has to be proportional to the skills of the person maintaining it, which is why you collaborate with them. But that person and their skills will need to be paid for and so you need to talk to the money people. Economic system you are working in will directly influence your technology, because the more complex the technology, the more expertise you need, the more likely it is things are going to be a little more on the expensive side. People with advanced technological skills are not cheep. They make a lot more money shooting down bugs all day in a monster tech organisation then being the IT person in the GLAM sector. And this is not just money for a set amount of time, this is labour needed to maintain an archival object – this goes on forever. So getting feedback from the money people on any solutions you are developing your solve your wicked problem, your particular case of “how do we make oral histories reusable within my institution?”, is invaluable because the truth is money does make the world go round. So recruiting them into your little collaboration crew is essential.

Now what I have talked about so far is basically the mechanics of oral history reuse. How you use an appropriate technology to get your oral history recording from A to B from a WAV file to useable, searchable interface and keep it there. But you cannot just simply just go from A to B with oral histories. I have done three different placements for my PhD and in during all of them I was trying to make archival material reusable. I spent those six months not thinking about technology but working on either copyright, data protection, or sensitivity checks. When you are working with oral histories you are dealing with people’s lives, permissions and restrictions have to be in place in order to make it available. Which is why alongside your tech developer, your maintainer, money people, you have to have your copyright team, your data protection team, and maybe some kind of ethical review team. And again, just like obsolescence in technology collaboration is crucial because ethics changes all the time. Copyright in the form we know it now was heavily influence by the internet, which is relatively young. GDPR was only implemented in 2018. And what language and images are deemed socially acceptable is always changing. The feedback you get from the ethics people to keep your ethics up to date is so important, because most institutions in the GLAM sector cannot really afford a lawsuit or scandal, so you need to get this right.

It is getting busy our collaboration crew but have one area of wickedness left, value, and this is where things start to get really sticky, because all I have talked about so far is about making reusable oral histories not about actually reusing them. You can lead a horse to water but you cannot make it drink. You can make your oral histories as reusable as you like but if people do not want to reuse oral histories they are not going to reuse, even if its easy to do. They have to see the value in reusing.

And this is where I mention trait 8 of wicked problems “Every wicked problem can be considered to be a symptom of another problem”. The difficulty of reusing oral histories is a symptom of the problem with how we value historical material. And how we value historical material is a wicked problem in itself because you can value things in so many different ways. The classic way is it monetary value. Within this frame oral histories are not going to fair to well against other historical items like chairs, paintings, original Beatles lyrics. In total I have seen the National Trust used eight different ways to value material:

Communal – The item represents a particular community.

Aesthetic importance – The item is deemed ‘aesthetically’ important or is from a famous artist.

Illustrative / historic – The item is illustrative of some historic moment.

Evidential – The item works as evidence to see how something was.

Supports Learning – The item is helpful in supporting learning found in the national curriculum.

Popular appeal – The item has mainstream appeal.

Cultural heritage significance – The item is significant to a specific culture.

Contextual Significance – The item gives important contextual information to a site, or a historical event

Materials also have international, national, regional or local value.

You can also flip the idea of value, how much is it going to cost to keep this item? This can again be measured several ways for example money and space, but also carbon. How much energy will it take to keep this item? Yep the reusing of oral history is an environmental issue.

Value is complicated and in order to get people to reuse oral histories we need to understand all the value oral histories can offer. We need to talk to curators, artists, educators, community workers, academics, all the potential different reusers and ask them what they find valuable. Why would they reuse oral history? And then we need to think about how we communicate this value. Do we go top down and work with policy makers to develop policy which makes it a requirement to reuse oral histories? Or do we work bottom up and try and nurture a culture of oral history reuse by teaching it more at a university level and creating projects based around reuse? Although whether a project based solely around reuse will get funding is another question, which brings us back to the money people and proves the wicked entanglement of it all.

This is not a banal, tame problem. It is a wicked problem – a mess. These five areas, well four overlapping` areas and a continent of complexity, are deeply intertwined and this is before we even start bringing in the unique elements of each individual institutions case of oral history reuse. And the only way to start detangling in some way without failing or being destructive is by collaborating and create a solution that will bring us a step closer to reusing oral history.

[1] “we stumbled onto digital technology for oral history under the false assumption that it would save us money and personnel in the long run.” (p. 19)

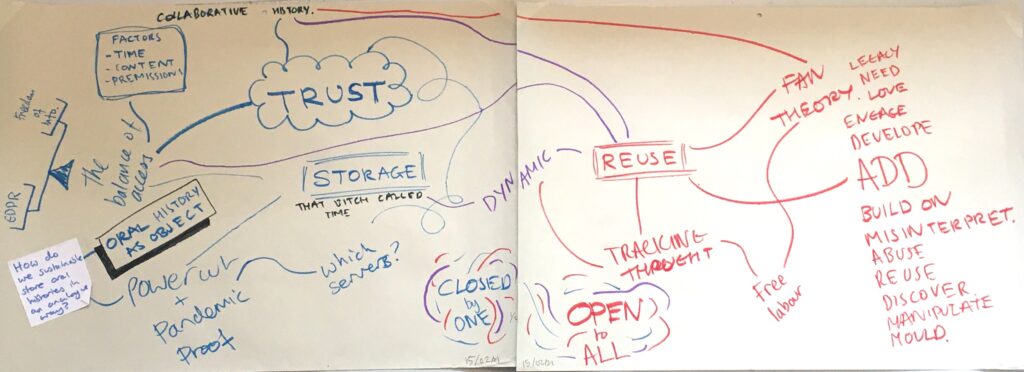

OHD_WHB_0247 Miro board of the NCBS away day

OHD_WRT_0179 Summary of thinking Spring 2021

Summary of thinking

In this rather tumultuous world I think that this CDA currently addresses three points of change: the digital invasion, the history review and collaboration fever. When I refer to the digital invasion I am specifically talking about the digital’s influence in the GLAM sector, which pre-pandemic was already making its mark through pressure to digitise collections but now has had a rather large boost due to many of the brick-and-mortar buildings being closed for long periods of time causing institutions to move everything online including exhibitions. The second point of change encompasses several discussions people are having about how we represent our history today. Contemporary issues, like the Black Lives Matter movement, the #metoo movement and climate change have caused people to demand a review on how we represent the past, wishing for it to be more inclusive and better reflect the stories of minorities. The final point of change, collaboration fever, addresses the increasing interest in interdisciplinary projects both in- and outside academia.

Within each of these points of change there are conflicts, clashes and collisions that are happening. These often take place around the symbols and languages we used to communicate in each sphere. For example in the digital invasion we can find a clash between the symbols and languages used by the digital realm and the archival realm. Where the digital is fast and shiny, the archive is slow and dusty. When searching the digital the user relies on pre-inputted keywords while archival searching relies on the creative knowledge of the archivists. What each sphere returns from a search is also in opposition; the order digital list versus the somewhat messy archive box of stuff. Here I believe the challenge is to soften and slow down the invasion of the digital as I am pessimistic that it will be able cure all the problems that brick-and-mortar archives presently experience.

The conflict found in the history review is clearly based around the symbols and language we use to discuss our history and what affect it has on modern society. Where one sees a symbol of the Great British Empire another sees a symbol of the slave trade. Where one generation sees coal as a symbol of a way of life that was destroyed, another views it as a symbol of pollution and an unsustainable industry. The problem here is that currently people approach this discussion in two very extreme ways; either they ignore it completely or they turn it into a war of identity. The challenge inside this point of change is to create a space for a more nuanced discussion.

The clashes that happen within the last point of change I have experience first hand many times. Every field of research has its own accompany culture, language and habits. When people collaborate across disciplines they bring this baggage with them. This can lead to clashes and confusion as symbols can mean completely different things in different fields. However, this clash of cultures is not the only problem within this point that I am concerned about. My biggest qualm with this point, and why I refer to it as collaboration ‘fever’, is that there is a growing romanticism around the language used in the area of collaborative projects. The gimmicky jargon, the token gestures and the ritualistic methods can, in my opinion flatten, and mute the collaborative process. This is an issue that is being picked up on by different people in the field of design. They are critical of how people are packaging their ‘methods’ into toolkits and selling them on to non-designers, which reduces the process into a tick-boxing exercise instead of a critical, thoughtful and difficult collaborative process.

So how do we tackle the challenges within each of these points of change? My current proposal is replacing these clashes of cultures and frustrating discussions with dialogue. In his book On Dialogue David Bohm describes discussion as a game on ping-pong where the focus is on defending ones truths against another’s. In contrast dialogue is focussed on creating a collective culture and an overall shared meaning. I imagine that creating this collective culture is far more sustainable for our points of change than the current discussions that are happening.

In case of our first point of change dialogue can be used to slow down the invasion of the digital. Where currently the digital is imposing its culture onto the archive, through search bars and keywords, dialogue offers the opportunity for the culture of the archive to inform the digital. Having this exchange of ideas instead of one field dictating to another opens the door to creating new creative technologies, rather than having this constant battle between cultures. We instead create a new set of cyborg symbols and languages, that in addition offers the opportunity to make both areas more inclusive. Where currently the digital sphere is for nerdy techies and the archive is for nerdy academics we can create a new space for all nerds.

Transforming heritage sites into places of dialogue is already happening with ventures like the International Coalition of Sites of Conscience founded by Liz Ševčenko. In her paper on the subject of the Sites of Conscience, Ševčenko emphasise the need to implement dialogue into the management of heritage sites as a way to not suppress conflict but instead view it as something that should be “embraced as an ongoing opportunity.” This should be one of the targets in order to make it sustainable beyond the timescale of the project.

The role that dialogue can play within collaboration fever is creating a space where we are aware of each person’s cultural baggage, but also make a space where we constantly question the process of collaboration. Hopefully we will then we able to harvest a more holistic picture of the collaborative process rather patting ourselves on the back for completing certain tasks and achieving specific outcomes.

So how do we create a sustainable dialogue that address all three points of change? Currently my suggestion is make things, together, all the time. In my opinion we should make things because it makes the dialogue more tangible and easier for those who were not there to understand the thought process. It also causes people to buy into the process more, make them feel like they are part of something and are being heard. This making needs to be constant, because every time we make something it is essential that we reflect on it in order to fully understand the process and avoid this project becoming an exercise in ticking boxes.

Now there comes a point where we need to capture this ongoing process. At the end of the three years we can show the results of our making in a conclusive way through an exhibition or oral history project or an archive. However, it is of utmost importance, as I have previously touched upon, that we analyse this constant collaborative making in a way that allows it to live beyond the three years of this project. Otherwise all the preaching about sustainable dialogue is completely undermined.

To summaries this project deals with three points of change: the invasion of the digital into the GLAM sector, the conversation surrounding changing attitudes to our past and the increasing interest in collaborative work. Each of these points of change have areas of conflict based around symbols and language that in my opinion can be combated by creating a sustainable dialogue through constant collaborative making. Hopefully this process will result into something that lives beyond the time limit of this project and can be adopted by other parties who wish to embark on a similar venture in the future.

OHD_WRT_0175 Interim Crit Plan

Here follows a basic plan for interim crit sessions that I believe will help my work. The general aim is for me to get feedback on my work but also to bring together various stakeholders for further knowledge exchange. I imagine there will be two types of crit sessions, one AFK (away from keyboard) and the other on Zoom. I think it best for them to take place near the end of this calendar year.

AFK Day

There is the option to have AKF days at different locations, one at Newcastle, another at Northumbria and one at Seaton Delaval Hall. What I plan to do is have an exhibition of my work which people are able to visit throughout the day and also have scheduled sessions where people have a round table discussion about my work. When it comes to capturing people’s feedback, the discussions can be recorded and people will be also encouraged to leave comments on my work either via a feedback or post-its.

Zoom Day

The Zoom day will be similar in structure; there will be a Miro board that functions as a type of gallery space and scheduled round table sessions. Although it might also be helpful to send round a collection of my work before hand. Feedback again will be captured in a similar way as I can record zoom sessions and people can leave comments and post-its on the Miro board.

OHD_MDM_0024 Mind map storage versus reuse

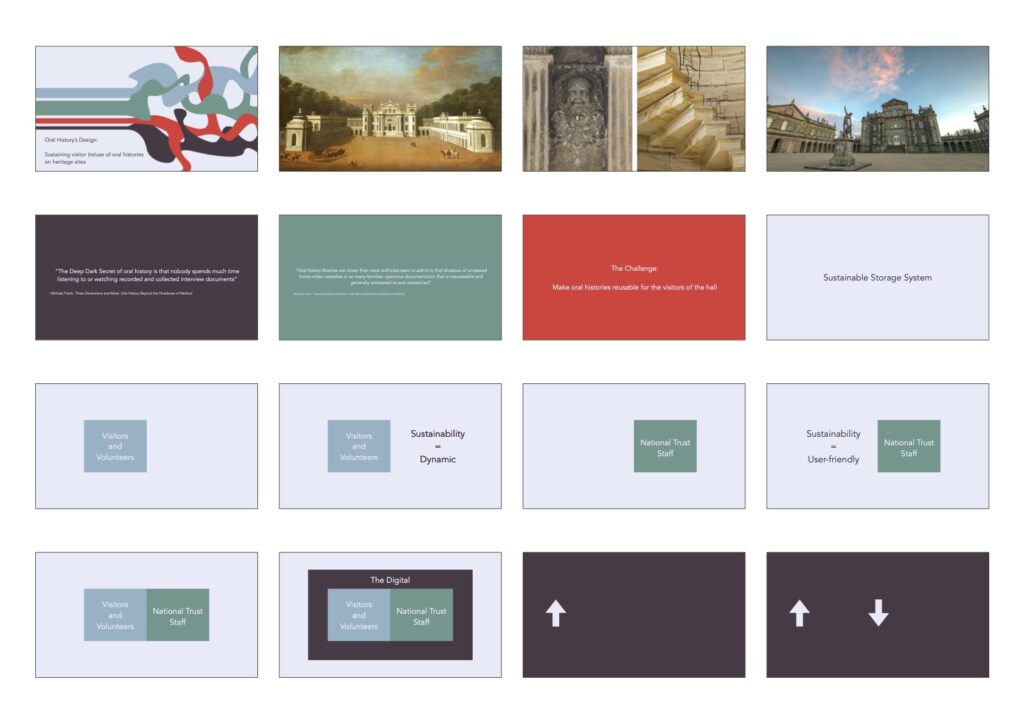

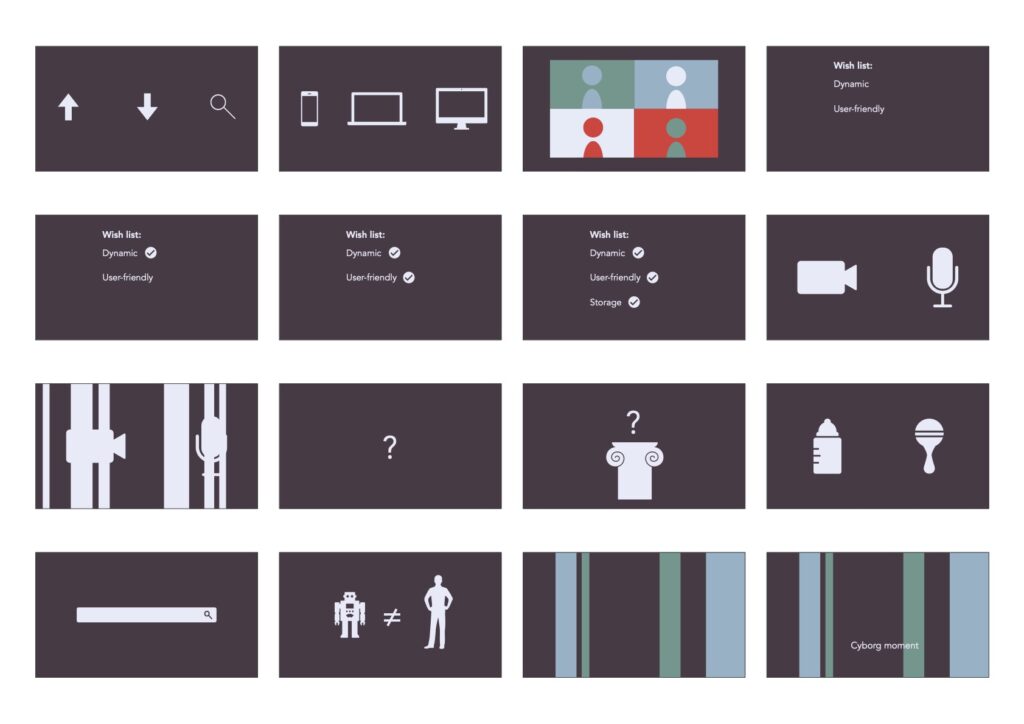

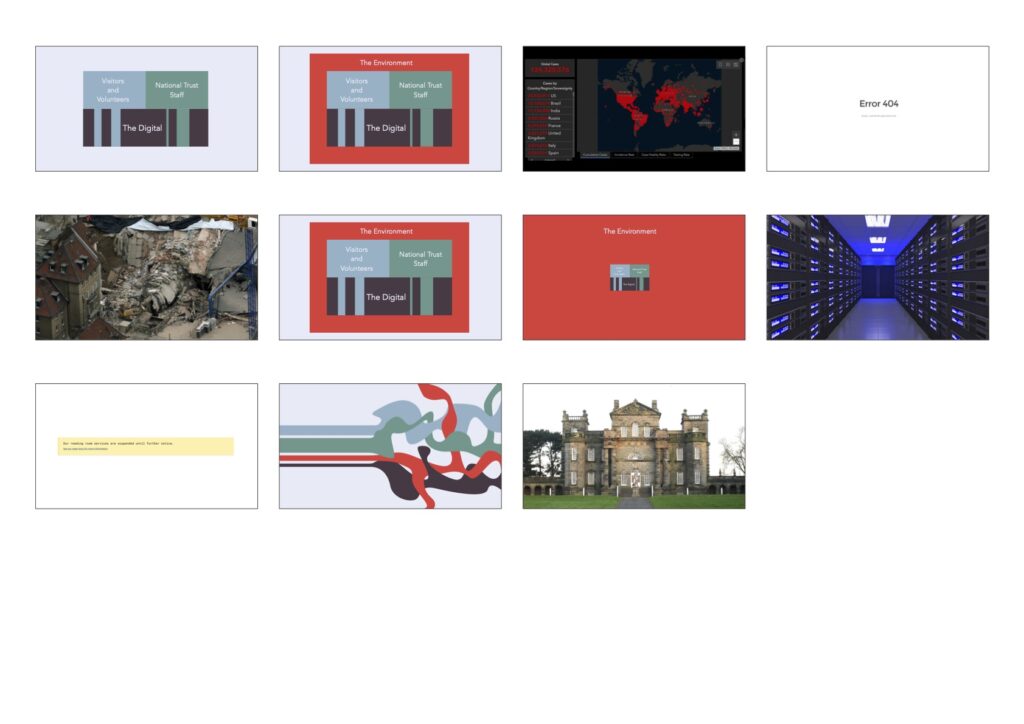

OHD_PRS_0125 Oral History’s Design: Sustaining visitor (re)use of oral histories on heritage sites

On 26 March I presented my first paper during a series of Digital Heritage Workshops organised by Lancaster University and IIT Indore. It was really scary and weird. I didn’t feel looked after at all. I also presented something that had already been discussed by previous speakers. Anyway you live and learn.

Script

This is Seaton Delaval Hall. Built in the 1720s the hall and its residents, the ‘Gay Delavals’ became renowned for wild parties and other shenanigans. In 1822 the hall went up in flames severely damaging the property. This history is represented very well in the collection that is housed at the hall which is now run by the National Trust.

What is less represented is the more recent history. The community that looked after the hall after it burnt it down, when it was a prisoner of war camp during both wars and later when the late Lord Hastings invited the local people to parties after its restoration.

This history lives within the local community. Luckily we have the wonderful field of oral history that allows us to capture this predominately undocumented history.

However oral history has a deep dark secret. After recordings have been made and analysed, they are locked into an archive or into a historians cupboard and never heard from again. They are like a box of unwatched home videos.

This in the context of Seaton Delaval hall seems sad as its strength as an institution lies within its deep connection with its surrounding area. It would therefore be a shame if the community who gave these histories cannot access them. I also personally think this to be ethical dubious as the lack of access to these oral histories brings up issues of power inequality where an institution like the National Trust happily takes the oral histories but not giving something in return.

SO this is the challenge: we want to make oral histories reusable for the visitors of the hall.

To make the rather complex problem more tangible I have focused in on the idea of sustainability:

I would like to point out here that I am using the term storage system instead of archive because I feel that the idea of the archive is very loaded and cultural represented as not particularly accessible to the masses.

Let’s start with the visitors and volunteers. This particular group, especially the volunteers, are the people who will contribute and donate their oral histories to the hall. Now because of the standard time and financial constraints the period of recording will not be able to capture all the stories. So this system that will house the the initial recordings needs to be dynamic and sustainable enough for the visitors and volunteers to keep adding and reflecting on the history.

For the staff the term sustainability addresses user friendliness. It needs to be easy for a new staff to learn how the system is use and managed.

This is where I believe the digital can help.

The digital as we are all fully aware has the amazing capacity to allow people from across world to upload, download, browse all sorts of content. It’s awesome. Also as time goes on more and more people are getting familiar with the digital sphere. Especially with the pandemic which forced to many use it more. This is not just individuals but also the case for most institutions notably those in the culture sector who have been very busy trying stay afloat by working out how they can use all these digital tools to keep their audience. The digital and its tools have become and are increasingly becoming part of everyday life.

The dynamic and sustainable requirement of the system, where people can easily add information and stories is pretty covered by basic digital systems.

The user friendliness can be achieved if the staff are involved right at the beginning with the design of the system. Allowing it to mould to the staff’s digital habits and knowledge.

What the digital can also help the staff with is storage. The digital is able to store documents in also sorts of formats and in all sorts of locations. I personally find that the internets ability to duplicate (think memes) might be a possible tool that could help storage issues but that simultaneously brings up all sorts ethical issues around permissions and copyright.

However what the digital also has done is created this desperate need to record and store everything and therefore also a huge sense of loss when something isn’t captured. Because as you are able to capture and store something you also create a whole bunch of things that arent captured and therefore lost. Technology has always played a huge role in this, just look at the field of oral history which relies completely on the ability to record someone’s voice. So then the question is should we record everything? Do we need to record everything? It’s tempting when you can record everything. But then you have everything and that is also useless because you cannot reuse everything. One of the archivists at the Parliamentary Archives once told me that they had calculated how long it would take for them and their colleague to digitise everything and it was 120 years. This paradox brings up issues around value. What do we value? Whose voices do we value? But an even bigger problem is what will we value?

This one of the bigger I imagine we will be dealing with in the next couple of years. Trying to keep the digital eco system healthy and not complete collapse under its own weight.

The digital is still very young. Which is proven by what it can do really enthusiastically like record everything and allow everyone to contribute. But it is also proven by the gaps that has. For example many search functions on online archives are difficult to use and don’t deliver that same serendipitous feeling that brick and mortar archive has. A search bar is not close to being the same as an archivist who knows the collection. Robots are not completely ready to replace humans just yet. For now humans will have to fill in the gaps that the digital has.

A good example of this blend of human and digital is that people who are unable to do their research because they cannot go into archives or the digitisation of the document they are interested in is not good enough. What I have seen many people do now is use their human network to access these documents by ringing people up and asking them take pictures of documents. I thought this was a funny cyborg-y moment where people needed both technology and a human person to achieve their goal.

So what we are looking at is how the digital can support the needs of humans at Seaton Delaval Hall by adapting to their needs. But at the same the humans are free and able to fill in these gaps that are present in the digital.

However there is one more layer I would like to add to this challenge of building a sustainable storage system. And that is the environment. Our environment heavily influences whether we can access archives. A pandemic can shut us off from the brick and mortar archives. A power cut can take down the servers where the digital archive stored. Or an earth quake or storm can destroy both completely.

This in addition to digital gaps is why I do not believe that it is sustainable to solely relay on either a digital or a brick and mortar storage system. A system that floats between these two worlds and at its centre has the humans that are reason for its existence, that I believe is the closest we might get to having something sustainable. Something that will allow Seaton Delaval Hall and its community continue telling stories for generations to come.

Slides

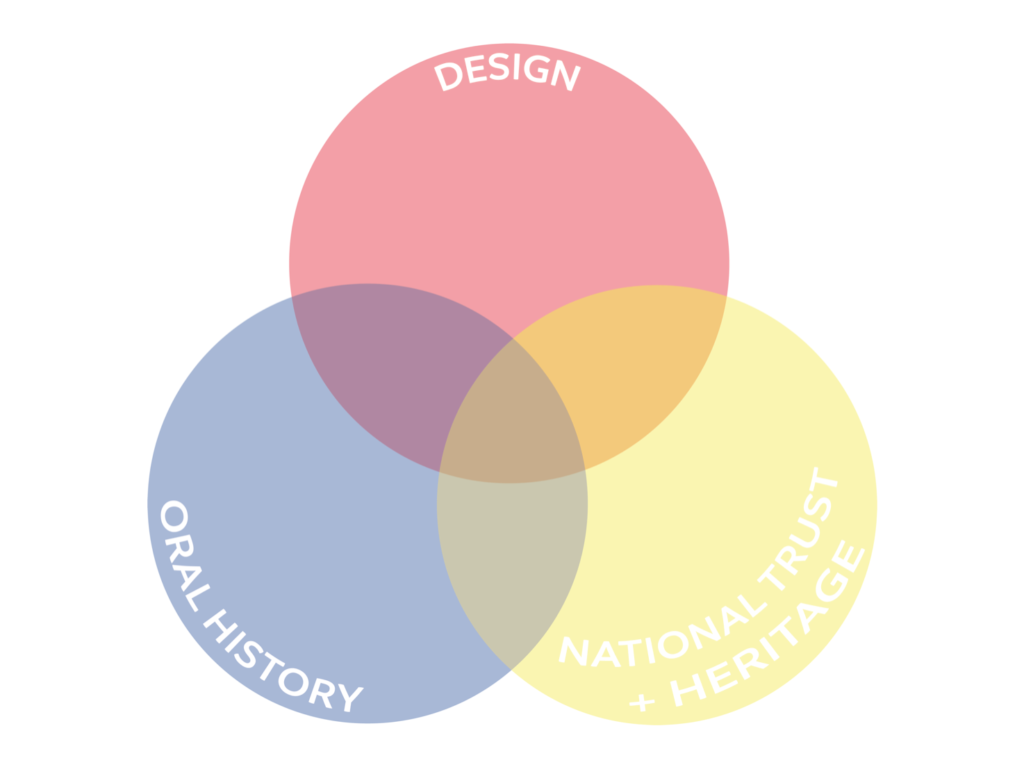

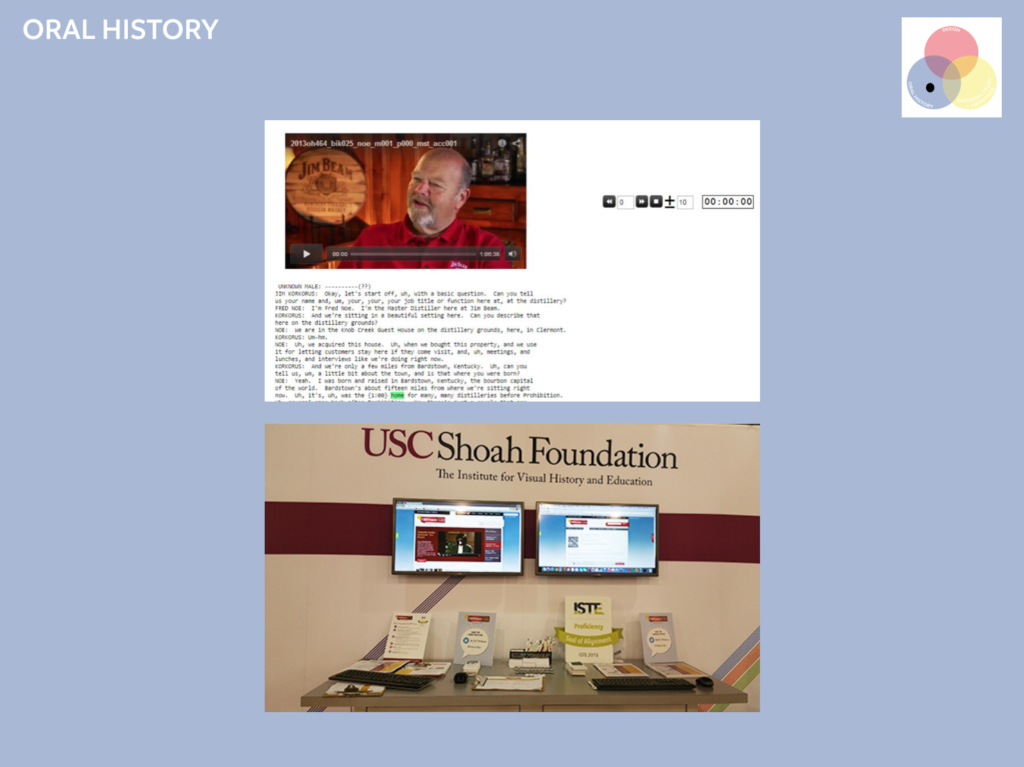

OHD_PRS_0124 Presentation/Interview

Below is the presentation I had to do in order to be chosen as the student to complete this PhD. The interview took place on Feb 18th 2020 and the question I had to answer was, “What are the key challenges and opportunities [in this PhD] and how will you address them?”

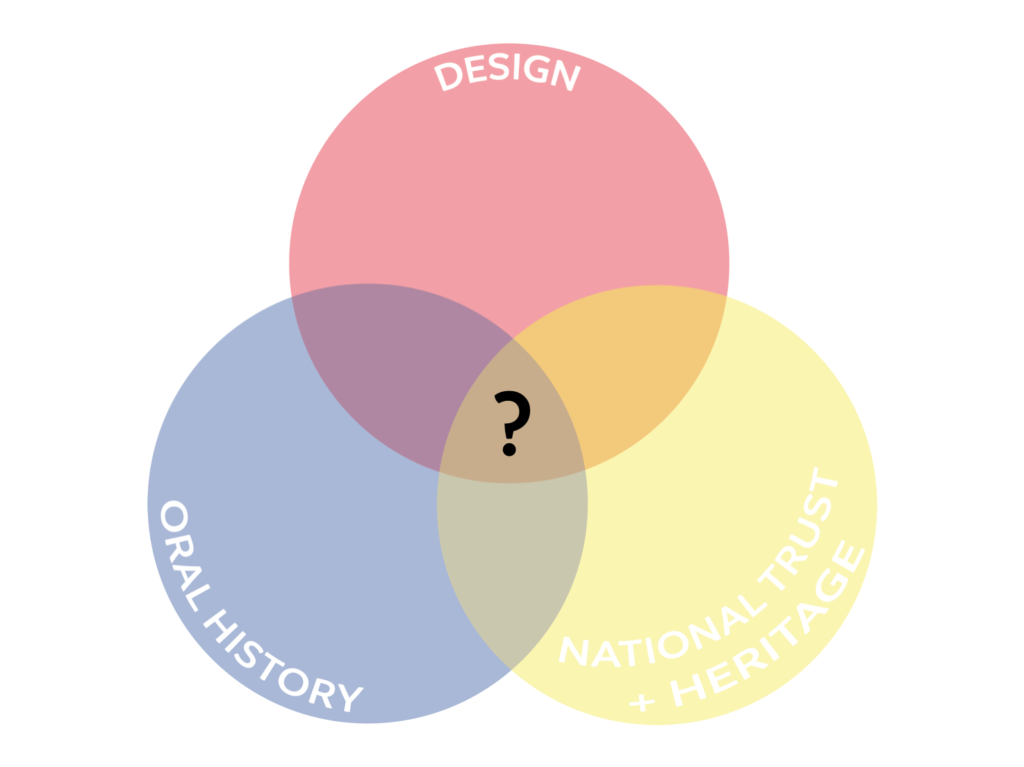

SLIDE ONE

I have set this presentation up as a Venn diagram of three main parties of this CDA: National Trust and the heritage sector, Oral history and Design. In order to answer your question, I will navigate through the various sections of the Venn diagram identifying opportunities, challenges and how will address them.

SLIDE TWO

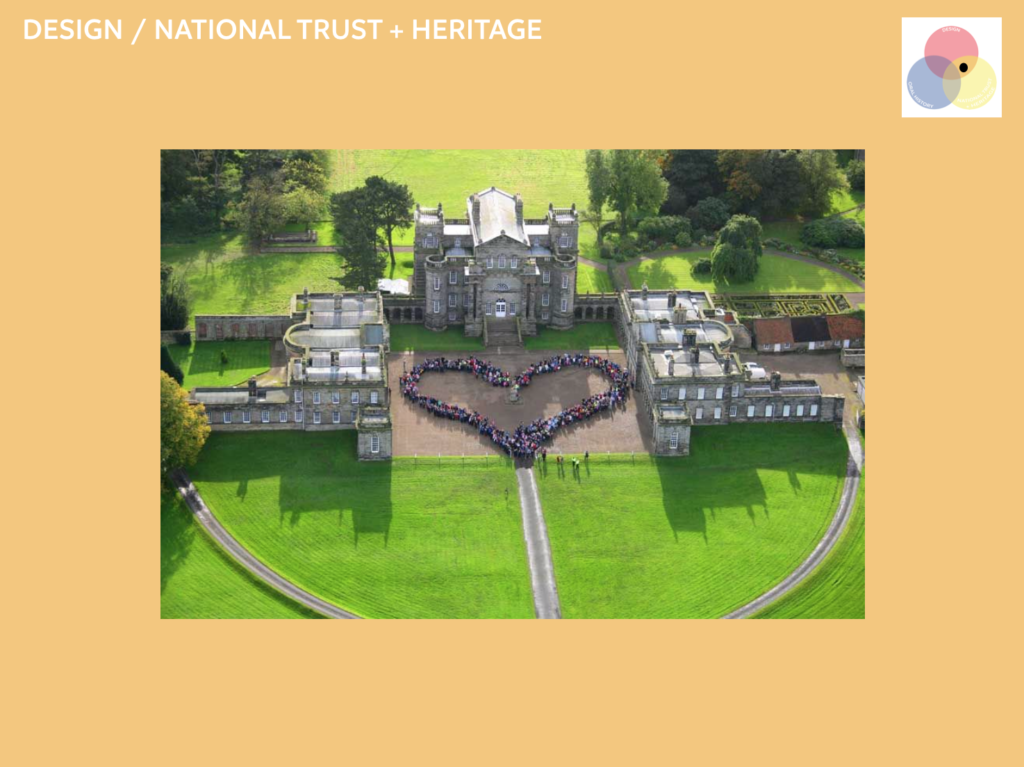

I think the first opportunity lies with the National Trust property Seaton Delaval Hall. If you observe the setting and history of the Hall you will find it to be the appropriate setting for this CDA. Firstly, the Hall is in the middle of a wide and rich community. Over hundreds of years the Hall and its inhabitants have contributed to this community and return the community has also given back with the most recent example being the money that was raise to help the National Trust take over the property. Secondly, it is a relatively young National Trust property. By that I mean that it has only been acquired by the National Trust in the last 11 years, meaning that until very recently; stories, memories and histories were being made at the Hall. Seaton Delaval Hall is therefore a perfect candidate for any oral history project, however a recent collaboration between the National Trust and MA in Multidisciplinary Innovation at Northumbria University makes the Hall the perfect location for this CDA.

SLIDE THREE

In May 2019 as part of the Rising Stars Project the National Trust came to Northumbria University with hope to collaborate in setting up a new oral history project. I was part of the team on the Multidisciplinary Innovation MA that was given the challenge of creating a new, an innovative method for collecting, archiving and displaying oral history. We started off by investigating methods of collecting group memories, as at first we found the National Trust’s current prescribed method of collecting oral history too formulaic. We concluded that due to the aforementioned setting of the Hall there should be a focus on reengaging the local community through this oral history programme. So we wanted to create a more participatory type of oral history that reveal a bigger picture of the Hall and created a sense of collective ownership of these histories. Instead of the “rather odd social arrangement” of the one-to-one interview, as Smith describes it in Beyond Individual / Collective Memory: Women’s Transactive Memories of Food, Family and Conflict, the team wanted to lay the power of the narrative with the participants instead of the interviewer. What we wanted to avoid is what the historian Lynn Abrams experienced while working on a project about women’s life experience in the 1950s and 60s. During that project she found that her position as an expert in women’s and gender history and implied feminist meant that her participants adapted their story to fit the wider feminist narrative. However, as our project progressed and the team dove further into oral history theory we started to understand the importance of individual interviews. Especially because during the testing of our group interviews we found that some people were less comfortable with the group setting and therefore would contribute less.

SLIDE FOUR

So, after three months of research, designing, testing, refining and testing again we developed two new group-interview methods alongside an incorporated individual interview. We also created several ways to display oral histories around the property, and potential new methods of archiving oral histories. Despite the high level of outputs the project only really scratched the surface, however it gave the opportunity for this CDA to exist in the first place. I view this project as the launchpad for this CDA. What it did was start an exploration into collective ownership and the role of community within the context of oral history at Seaton Delaval Hall and it brought together the various parties sitting here today. But most importantly it revealed that it would require more time and effort for it to be successful. This is especially the case with archiving, which was purposefully left open ended by the team, because as we producing all the previously mention outputs we discovered that oral history archiving is a very difficult problem.

SLIDE FIVE

Micheal Frisch discusses difficult problem this extensively in his paper ‘Three Dimensions and More’. He describes oral history archives as a shoebox of unwatched family videos and outlines various paradoxes that occurs in oral history archives. One of the paradoxes, the Paradox of Orality, refers to the inappropriateness of the reliance on transcripts in the context of oral history. Many oral historians, including Alessandro Portelli, agree that using transcripts in archiving reduces and distorts what was originally communicated by the interviewee. Although there are many archives that rely on transcripts, there are also archiving systems being developed that tackle this exact issue. Certain systems are already engaging with this paradox by using various forms of technology. Such as the Shoah Visual History Foundation, set up by the film director Steven Spielberg, where video testimonies of holocaust survivors are indexed, timestamped in English and can be navigated along multiple pathways. Another example is Oral History Metadata Sychronizer (OHMS) created at the Louie B. Nunn Center for Oral History at the University of Kentucky Libraries, which can be navigated by searching any word and it will jump to the exact moment that person is talking about the searched word (Boyd). I imagine throughout the CDA these systems, including the more analogue archives need to be explored further in order to uncover the opportunities for innovation. What we are specifically looking for is the opportunity to create a system that is not driven by technological advancements, but by a desire to change the culture of how we use archives.

SLIDE SIX

Currently, we use all types for archives in a static way, which is the opposite to how we treat history. Not only are we constantly making new history through the passage of time, our attitudes towards history constantly changes. For example the global discussion surrounding artefacts in the British Museum or even attitudes towards mining. Recently I worked with the arts and education charity Hand Of at the Durham Miners Hall with children from the local area. Working with these children you see that they view mining through a completely different lens to the generation that came before. While you and I might associate mining with the miners’ strike and the deindustrialisation of the UK, these children view mining as something from the pass, something important to the previous communities but ultimately something unsustainable and bad for the environment.

The static nature of the archives is in complete contradiction to how people experience history. I believe this CDA is looking for is a more sustainable and dynamic preservation of stories. A system that taps into the ever changing zeitgeist reflected in its visitors instead of keeping everything frozen in time.

Well the CDA is called the ‘Oral history Design’. In my eyes I see design the provider of tools for exploration, with Seaton Delaval Hall providing the test subjects. This CDA would not be possible if it was not for the resources that the National Trust has to offer. Those resources being the visitors, the volunteers, those who provide the histories and the team working at Seaton Delaval. I believe that in order to create a system that is truly sustainable it needs to be tested at every point of the process and the collaboration with the National Trust gives us that opportunity.

SLIDE NINE

The challenge however is finding the appropriate design tools. Design intervention and the use of design thinking tools can deliver high rewards but it can also cause considerable damage if not use responsibly. Not only do I expect to do more research into design methods on top of the ones I am already familiar with. I also expect to constantly be reviewing, adapting and modifying the tools and design process as project progresses. This is something that is highly encouraged by many people in the field of including the Kelley brothers, from IDEO, who openly invite people to adapt their methods and Natascha Jen from Pentagram, who argues that design thinking is more of a mindset, not a diagram or tool. Within this CDA this might evolved into regular reflection on the process both from myself as the student and from the other parties involved. All of this is especially important because the collaboration between design and oral history is a relatively new and unexplored territory.

SLIDE TEN

This unexplored territory, however gives the CDA opportunity to explore something in addition to the creation of a new archiving system; the methodology behind cross-disciplinary work within the academy. Cross-disciplinary work is nebulous and struggles to be categorised within the academic system. As I found throughout my MA there is a lot literature that talks about interdisciplinary, transdisciplinary, multidisciplinary, cross-disciplinary work. These papers, books and articles talk about bringing various parties together in order to solve a problem but it is nearly always in the context of business or social enterprise. The CDA will therefore offer us the opportunity to research and experience multidisciplinary or cross-disciplinary work within the context of a university.

However, cross-disciplinary, transdisciplinary, interdisciplinary, multidisciplinary work, whatever you would like to name it, does come with its fair share of challenges. I am familiar with this as during my MA I had to work in an 18-strong team of people from a diverse range of ages, ethnicities, nationalities and socio-economic backgrounds and different fields of work. Throughout the year it was clear that one of our biggest barriers was communicating across these differences. It often felt like I was speaking a completely different language, which sometimes was the case, as certain ambiguous words were perceived differently depending on the person’s background. I predict this to happen throughout the CDA, not only across the design and oral history but also with the National Trust and any additional parties that might be involved.

SLIDE ELEVEN

It is essential that we have as many of these cross-disciplinary conversations as possible. Roberto Verganti, in his book Design-driven Innovation, refers to these types of cross-disciplinary conversations as a ‘design discourse’ – experts from different backgrounds exchanging information. Verganti finds this to be essential in design-driven innovation, an innovation strategy that pursues change through a reinvention of the meaning of a product or system instead of relying of technology. Which is exactly what this CDA is looking for.

This design discourse needs to be managed and organised efficiently, which I feel confident I am capable of doing due to working in teams throughout my professional and academic work. Especially thanks to my MA and my work with Hand Of and teaching for the early English programme Such Fun! I know the importance of clear communication and disciplined organisation. I imagine that I as the student of this CDA, I will have to take a project manager-esque role in order to float between the different disciplines, communicating progress and finally managing expectations.

SLIDE TWELVE

And that really is the crux of it all, managing expectations, because you cannot guarantee anything. For all we know the answer to design oral history archives is – don’t, National Trust’s prescribed archiving method of electronic cascading files does the job perfectly well. For now this CDA is exploring the unknown, but that is what I like about it. I spent three years in a Goldsmiths art studio exploring the unknown, then I did an MA do to more targeted exploration of the unknown and now I have a narrow it down again in applying for this CDA. Exploring the unknown is full of opportunities and challenges, but you have to do it in order to find them and I very much like to do it.

The feedback a got on my presentation was good, however I did not do as well on answering the questions. This is a completely fair judgement as I felt slightly unprepared. I think it is important that I start planning out the steps I will be taking throughout the three years and deadlines for certain outputs.

OHD_BLG_0093 Oral History ➡️ Design

My masters in Multidisciplinary Innovation (MDI) taught me how design and its practices can be used in any field in order to create innovative solutions to complex problems. I believe that during this PhD I will use these techniques to help create a solution to the problem of unused oral history archives. This particular flow of knowledge I am completely aware of, however now I would like to discuss the reverse. How can oral history, its practices and its archives influence the world of design?

Let’s start with the reason oral history as a field exists. Oral history interviews are there to capture the history that is not contained within historical documents or objects. These histories often come from those whose voices have been deemed ‘unimportant’ by those more powerful in our society. It could be said that the work oral historians do is an attempt to equalise our history. However, oral histories, unlike more static historical objects and documents, are created in complex networks of politics, cultures, societies, power dynamics and are heavily influenced by time: past, present and future. Some oral histories take on mythological or legendary forms and are not necessarily sources of truth, but they do capture fundamentally human experiences that cannot be distilled into an object.

But how can this help the design world I hear you ask? Well, currently the design world is going through a bit of an ethical crisis. Ventures that started out as positive ways to help the world have brought us housing crises (AirBnB), blocked highways (Uber), crumbling democracy (social media etc.), higher suicide rates (social media), and even genocide (look at Facebook’s influence in Myanmar.) It’s all a big oopsie and demands A LOT of reflection. Why did this go wrong? How did this go wrong? What happened? Have we seen this before? How can we stop this from happening again?

We did a lot of reflection during MDI, but we also didn’t do enough. One, at the time we never shared any of our own reflections with the group and two, we now cannot revisit any of these reflections or the outcomes of our real life projects because they weren’t archived. The only documents I can access is my own reflective essays and a handful of files related to the projects, most of which solely document the final outcomes. This results in me only being able to see my own point of view and no process. Post it notes in the bin, hard drives no longer shared and more silence than when we were working in the same room. So what do we do if one of our old clients came to us asking how we got to the final report? Or after having implemented one of our designs are now experiencing a problem which they feel we should solve? Did we foresee it ? What are we going to do about it? I don’t know ask the others. It’s not my problem.

Now imagine this but on a global scale in a trillion dollar industry with millions of people (a relatively small proportion of the world) and very little regulation. And I am not just talking about Silicone Valley for once, but every global institution in the world. My supervisor told me that the World Trade Organisation once came to him asking for his help in setting up an oral history archive. The reason they needed this oral history archive was because they had all these trade agreements but everyone that had worked on them had retired and taken their work with them. They had the final outcome but not the process. Zero documentation of how they got there. Post it notes in the bin. They eventually did complete the oral history project but then did not have the documents to back these oral histories up because post it notes GO IN THE BIN. Whoops.

So, how did we get here?

In order to answer this question you need to be able to look back and see a fuller picture than your own point of view. We do this by not doing what the World Trade Organisation and MDI 2018/19 did. We create a collateral archive made of our post-it notes, digital files, emails etc. and we talk. We then put the collateral archive and the recordings of us talking together in one place. The reason we cannot rely solely on the collateral archive is because, as I said previously the documents cannot encompass the human experience to the extend that oral histories can. Also, not everything is written down some things will be exclusively agreed on verbally so the oral interview should (hopefully) fill in some of the blanks.

Once all this documentation has come together it needs to be made accessible to EVERYONE (with probably some exceptions.) This has two outcomes, firstly, it answers the question how we got here. People can analyse and reflect on the process in complete transparency. When something goes wrong we can look back and work out why. And secondly, in the case of design we now have a fantastic bank of ideas, a back catalogue of loose ends and unpursued trails of thought. Setting such a bank is already being examined in the field of design. Kees Dorst collaborated with the Law department at his university (I think) because he wanted to see how the Law department was able to access previous cases to help the present cases.

“Design […] seems to have no systematic way of dealing with memory at all” – Dorst, Frame Creation and Design in the Expanded Field p.24

In conclusion, people are increasingly aware that they need to capture their process in a constructive and archivable manner. Which is something I highly encourage for ethical reasons but also because archives are cool and you can find cool stuff in them. I am going to integrate this trail of thought into my PhD by being active in the creation of my collateral archive and also suggesting oral history interviews to be taken from all those involved.

(There is another reason why I would like to take oral history interviews of those involved, which hopefully is made clear in the ethics section of the site)

I hope that by integrating oral history into the design process it will push design into a more ethical space.