The Methodology Bit – Version One (very bad draft)

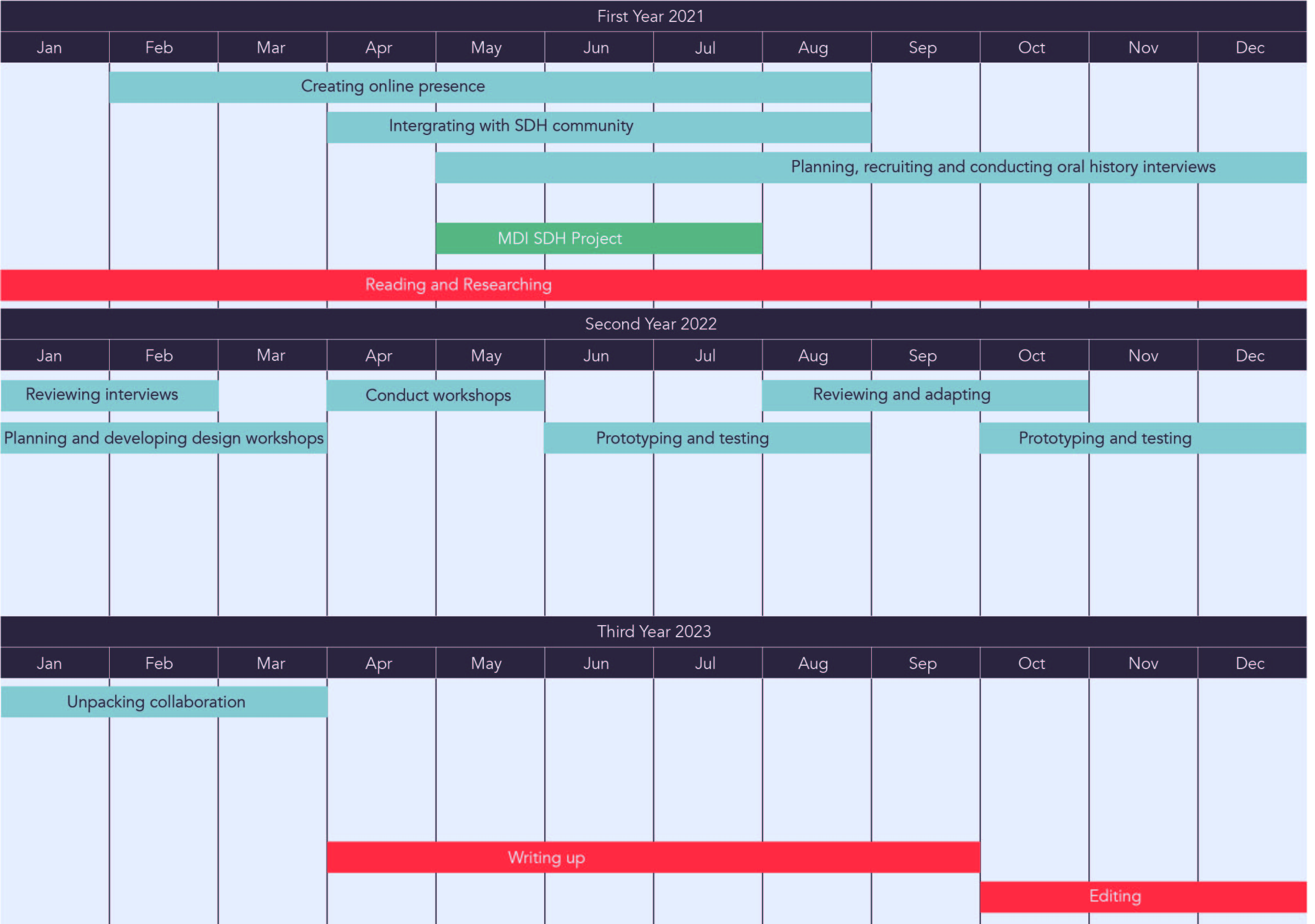

The above graphic was my initial project timeline. To say this is not how the project eventually played out would be an understatement. Both the initial chosen design methods and what I was intending on designing turned out to be highly inappropriate for the situation I was designing for. The central aim of my project was to develop a solution to encourage the reuse of oral history recordings, a problem infamously dubbed “the deep dark secret” of oral history (Frisch, 2008, p. 00). I was specifically looking at how to solve this deep dark secret with public history institutions, museums, heritage sites etc. My case study was the National Trust property Seaton Delaval Hall just north of Newcastle. I assumed I would make some kind of software or product to help ‘solve’ this issue, which would involve creating a prototype and then testing it out. However, within the first year it became apparent my plan was not going to work for two reasons. Firstly, my testing ground, Seaton Delaval Hall and National Trust were very risk adverse. The structure of the property and the National Trust in general is not a space where radical change or experimentation can happen easily, stability is key. Secondly, after researching the previous attempts of trying to solve the problem of oral history reuse, I realised me creating a new product was not going to work. There was something more fundamental that was being overlooked – maintenance.

Although there is little written on how certain attempts failed, what was written nearly always referenced how after the project money ran out the software or website fell apart (Gluck, 2014; Boyd, 2014, p. 9). This issue of oral history reuse is not about snazzy interfaces but about maintenance, politics, and wider complexities of institutions. Therefore, maintenance became the lens through which I did my project, specifically the way the performance artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles describes maintenance in her Manifesto for Maintenance Art 1969!. For Ukeles maintenance is: deeply undervalued in society; consist of many interconnecting boring tasks; and cannot afford to radically change (Ukeles, 1969). All three of these properties, but especially the latter two, led me to seek a methodology which could handle complex issues and be sensitive to the environment it is designing in, as I mentioned before the National Trust and the hall were risk adverse. I landed on Research through Design, a relativity young design methodology where the focus is not the creation of a product but creating new knowledge by using design methods (Stappers and Giaccardi, 2017). In my particular case this new knowledge would create a better understanding of how oral history recordings are/can/should be maintained. This in turn might lead to the development of more appropriate solutions to the deep dark secret of oral history.

I will unpack the concept of Research through Design or RtD and how it functions within the context of my project. Since the field of design is broad and there are the various interpretations of RtD, I will focus on the use and understanding of RtD within the field of Human Computer Interaction or HCI and Interaction design or IxD. HCI and IxD handle information technology and my work addresses the management of archive material, which is a form of information. Therefore, borrowing from HCI and IxD feels appropriate because their main purpose is to understand and design for the relationship between humans and their technology, which within my project can vary from analogue archive index cards to online catalogues systems. I will explain how RtD is explicitly suitable for researching and understanding maintenance systems, through its use of simultaneous problem and solution development, which originates from Rittel and Webber’s concept of ‘the wicked problem’. Following this I will focus in on what design methods I used as part of my research to generate knowledge. I will also explain how this knowledge and research is then presented in a way to demonstrate rigour.

Understanding RtD

RtD is a relatively young concept and it currently does not have a fixed methodology, which seen by some as a positive and some as a negative (Gaver, 2012). Although there is no strict definition of RtD there is consensus that, firstly, RtD as a method is excellent at handling complex problems, and secondly, the goal of RtD is to produce knowledge (Zimmerman et al., 2010, p. 311; Stappers and Giaccardi, 2017). The former is helpful to me because I am looking at the maintenance of oral history recordings in public history institutions. The latter is helpful because I was unable to do any thorough testing of prototypes as was originally planned, instead I will create knowledge which can help individual public history institutions understand and handle their own versions of the oral history reuse issue. To start with let us investigate the how RtD helps us understand maintenance infrastructures, and then move to looking at how creating knowledge is more appropriate for tackling this issue.

Wicked problems

RtD, like many other methodologies in design is focused around solving complex or ‘wicked’ problems. The term ‘wicked problem’ comes from the paper, Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning, by Horst Rittel and Melvin Webber. The origins of the wicked problem come from the 1960s where designer shifted from exclusively thinking about the product they were designing to thinking about the systems around the products and the wider systems of our society. These systems of our society were becoming increasingly complicated due to the rise of more complex technologies, and increased awareness of societal inequalities and the emergence of Post-structuralism, which challenged the idea problems could be defined in an objective manner (Bayazit, 2004, p. 17; Rittel and Webber, 1973, p. 156). What became apparent was how the Newtonian and more scientific problem-solving methods and theories used in the early half of the Twentieth Century could no longer handle the complexity of the post World War Two problems (Rittel and Webber, 1973). The types of problem which could be solved using this method, where a problem is easily defined, and solutions either fail or succeed, Rittel and Webber refer to as “tame” or “benign” problems. And the complex problems appearing in the latter half of the Twentieth century are referred to as “wicked problems”. Wicked Problems are societal problems involving multiple stakeholders and are of a complete opposite nature to benign problem. They are extremely difficult, if not impossible, to define and there is no correct solution, only ‘better’ or ‘not bad’ solutions (Rittel and Webber, 1973).

Through their explanation of the properties of wicked problems Rittel and Webber do give a simple structure to the ‘solving’ of wicked problems – simultaneous problem and solution(s) development. This has become the basis of much of design research in the last fifty years including RtD. The idea of passing between the editing of the problem definition and creating solutions is a way to continually challenge the underlying assumptions made during the initial formulation of the problem (Zimmerman, et al. 2007, p. 495). In order to understand why the wicked problem, simultaneous problem and solution development, and the continuous challenging of assumptions is helpful in the context of reusing oral history recordings within public history institutions, you need to understand the nature of maintenance.

The invisible web

In Ukeles’ manifesto there is the line: “Maintenance is a drag: it takes all the fucking time (lit.) The mind boggles and chafes at the boredom” (Ukeles, 1969). Maintenance and how it works is boring. The sociologist Susan Leigh Star makes a call for the study of boring things in her paper the Ethnography of Infrastructure, and although Star does not directly use the word ‘maintenance’ in her work, her idea of infrastructures has been used to better understand and unpack maintenance (Graham and Thrift, 2007). There are several of Star’s infrastructure properties which can help to understand maintenance infrastructures, such as:

- “Embeddedness” – Small maintenance infrastructures live within larger maintenance infrastructures (Star, 1999, p. 381). For examples, cleaners, janitors, and IT support are all part of a wider maintenance infrastructure of a building.

- “Reach or scope” – As is written in Ukeles’ Manifesto for Maintenance Art 1969! “It takes all the fucking time.” Maintenance is not a one-off event, it goes on forever (Star, 1999, p. 381).

- “Links with conventions of practice” – Those who work within an infrastructure will develop habits which are heavily influence by the technology they use. (Star, 1999, p. 381).

- “Built on an installed base” and “Is fixed in modular increments, not all at once or globally”- The maintenance infrastructure did not appear overnight it was built bit by bit in reaction to changes in the community it is meant to support or the technology it uses (Star, 1999, p. 382). And as Ukeles says there is little room for change once it exists (Ukeles, 1969).

However, it is specifically the “invisible quality” of an infrastructure, where the idea of wicked problems and simultaneous problem and solution development come in.

A maintenance infrastructure is a wicked problem. It is a complicated web of interconnected elements which is slowly, yet consistently, evolving in order to hold off any collapse. It is made up of technology, people, and their actions or labour which stops breakdowns from happening (Graham and Thrift, 2007, p. 3). These three aspects can be invisible in one way or another. Technology becomes invisible because it is buried underground like pipes or is suspended high above our heads like telephone poles. People can be invisible because maintenance workers are made invisible by either the location or the time the work takes place. For example, domestic workers stay in private homes and commercial cleaners work outside opening hours (Star and Strauss, 1999, p. 16). Within the context of my project the technology and the people are both invisible because the majority of work happens inside the closed doors of a storage space or office. The work associated with the maintenance and keeping of historical items, like oral history recordings, has always been invisible, however, like everything else, it has only gotten more complicated with the rise of technology. Technology has, in a way, opened up the storage space through the creation of digital archives, but this has also buried all those who maintain historical material deeper behind screens and servers. Actions or work can also be invisible. This is often emotional labour or other forms of care. A nurse is a great example of such a worker, because their work with patients is often “taken-for-granted” due to its completely intangible nature (Star and Strauss, 1999, p. 15). Oral history also has elements of invisible emotional labour because it relies on living humans to tell their stories. In order to ‘extract’ these stories the oral historians have to make the interviewee feel comfortable, which often involves many cups of tea.

In addition to the three main elements of a maintenance infrastructure being invisible in one way or another the outcome and function of a maintenance infrastructure also somewhat invisible. The main aim of a maintenance infrastructure is to keep things from decaying (Graham and Thrift, 2007, p. 1). However, because the product of the labour is a lack of decay it is difficult to quantify since there is no measurable outcome, only the absence of something, making it invisible. Everything about a maintenance infrastructure, the technology, the people, the work, the outcome, can or is invisible. These various elements are invisible in different ways making it additionally complicated. To solve the issue of oral history reuse in public history institutions we need to understand and map its maintenance infrastructure. This maintenance infrastructure and how it comes together is a wicked problem and the mapping of this maintenance infrastructure is equivalent to defining the problem in simultaneous problem and solution development. But in order to map the maintenance infrastructure we need to make it visible. Luckily how one makes an invisible infrastructure visible is relatively simple — you break it.

“The normally invisible quality of working infrastructure becomes visible when it breaks: the server is down, the bridge washes out, there is a power blackout.” (Star, 1999, p. 382).

You can see this with the previous attempts of solving the oral history reuse issue. Those who have written about it state how the eventual collapse of the website or software revealed how much the systems relied on the maintenance of digital systems (Gluck, 2014; Boyd, 2014, p. 9). The breakdown of the solution developed by these projects revealed part of the maintenance infrastructure for their particular situations. However, the information was only discovered after the project was finished, therefore the information could not be fed back into problem development.

Breaking the maintenance infrastructure to gain information for simultaneous problem and solution development is not an option; the system must keep maintaining. This is one of the reasons why the National Trust and Seaton Delaval Hall were worried about me widely testing prototypes, they were apprehensive to anyone who might disturb the delicate equilibrium they have in place. As I mentioned in the introduction the National Trust’s aversion to risk and testing, and the history of attempts to solve the oral history reuse issue led me to move away from designing a product. This is where RtD becomes different to other forms of design methodologies which also used simultaneous problem and solution development, because instead of creating a product or some other form of full realise system, it creates knowledge.

Knowledge, not a product

To understand why RtD focuses on creating knowledge rather than a product and why this is helpful within the context of mapping maintenance infrastructures through simultaneous problem and solution development, we need to look at how knowledge is defined within the terms, ‘research’ and ‘design’. Generally, research and design have often been pitted against each other, as Stappers and Giaccardi show in this table in their chapter Research through Design.

| Research | Design | |

| Purpose | General Knowledge | Specific Knowledge |

| Result | Abstracted | Situated |

| Orientation | Long-term | Short-term |

| Outcome | Theory | Realization |

Table 2.1 – In general, the terms ‘research’ and ‘design’ carry different connotations (Stappers and Giaccardi, 2017)

The definitions in the table above originate from the different types of ‘knowledge’ produced by academic and vocational forms of design education. Within the former, the ‘knowledge’ produced is in the form of research such as theories, frameworks, and matrixes, which can be used by others. The latter’s ‘knowledge’ comes in the shape of more tangible products for very specific situations (Glanville, 2018, p. 14; Stappers and Giaccardi, 2017). RtD sits somewhere in the middle where it produces knowledge which can be used by others but this is still grounded in the specifics of real-world application (Stappers and Giaccardi, 2017). According to Zimmerman et al. the outcomes of RtD can vary from new design theories, frameworks or philosophies to artefacts offering a possible new future, to tools to encourage wider discussion in the field (Zimmerman et al., 2010, p. 311). However, the goal overarching of RtD is to produce knowledge used to simulate conversations with interested parties about possible futures (Zimmerman et al., 2010, p. 311; Stappers and Giaccardi, 2017).

The knowledge created is purposefully ambiguous to make it more transferable to other situations and to allow it to be flexible when change does come. People are able to take the knowledge and interpret it for their own specific situation (Gaver et al., 2003). This recognises Rittel and Webber’s idea that a wicked problem is never truly solved, and each variation of the issue is completely unique (Rittel and Webber, 1973, p. 162, p. 164). Its ambiguity means it is removed from its specific situation and time; therefore it allows room for slow implementation, which is again essential to maintenance infrastructures because there is little room for radical change (Ukeles, 1969, p. 2). If a product was being created instead of knowledge this would not work. Creating a product is akin to the design description in the table above, specifically fixed in one location and time, this makes it difficult for others to replicate or use in anyway. Within the context of my work making something which does not need to be implemented immediately and can be used by other public history institutions is more suitable than making a product which cannot even be tested properly. By not having to do thorough testing of a product RtD can help avoid breaking the maintenance infrastructure. However, RtD still requires some form of simultaneous problem and solution development which by nature of the method would require some probing of the maintenance infrastructure. By using less invasive design methods in RtD you can navigate the delicate maintenance infrastructure and still do simultaneous problem and solution development.