Readings

Families remembering food: revising secondary data by Peter Jackson et al.

Secondary analysis reflection: some experiences of re-use from an oral history perspective by Joanna Bornat

Dynamic Attitudes

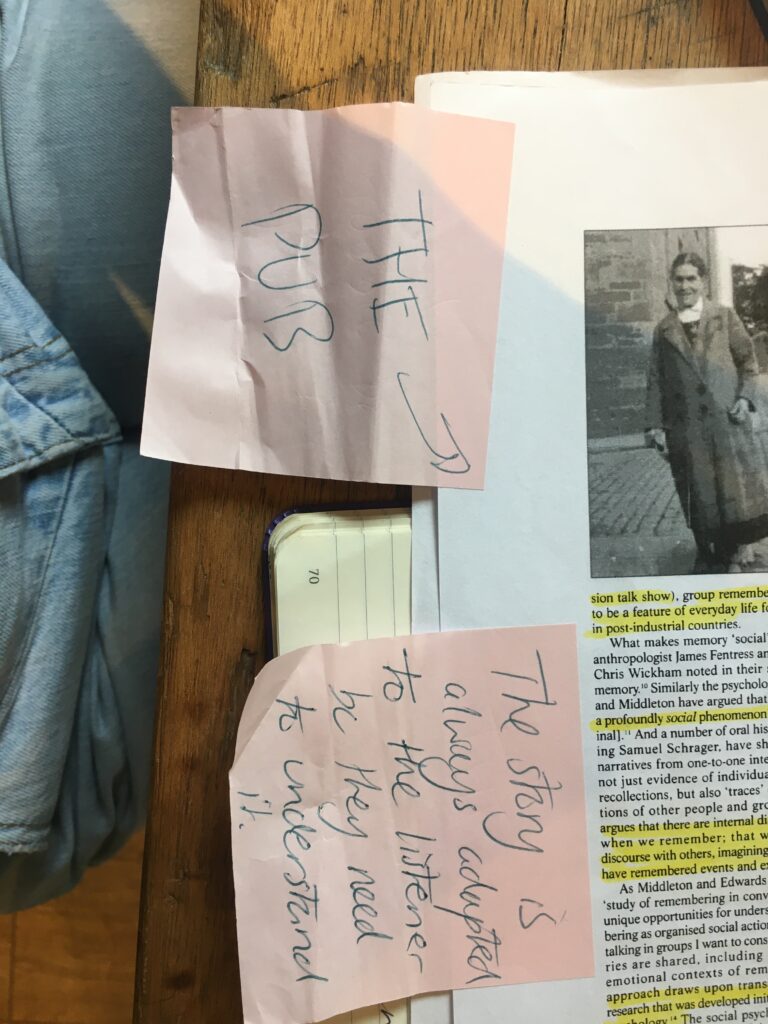

Everyone views the world through their own personal lens and academics are not exempt. If when an academic sets out on their researching journey they already have a vague idea about what they are going to write about. An oral historian will pick people to interview based on this idea and will ask questions that will fulfil this idea. However, many unexpected things can happen during research that causes you to change your attitude, readjust your lens etc. Your mindset evolves with the project and there is nothing you can do to stop it. This is why constant reflection is so important because our thought process is never static.

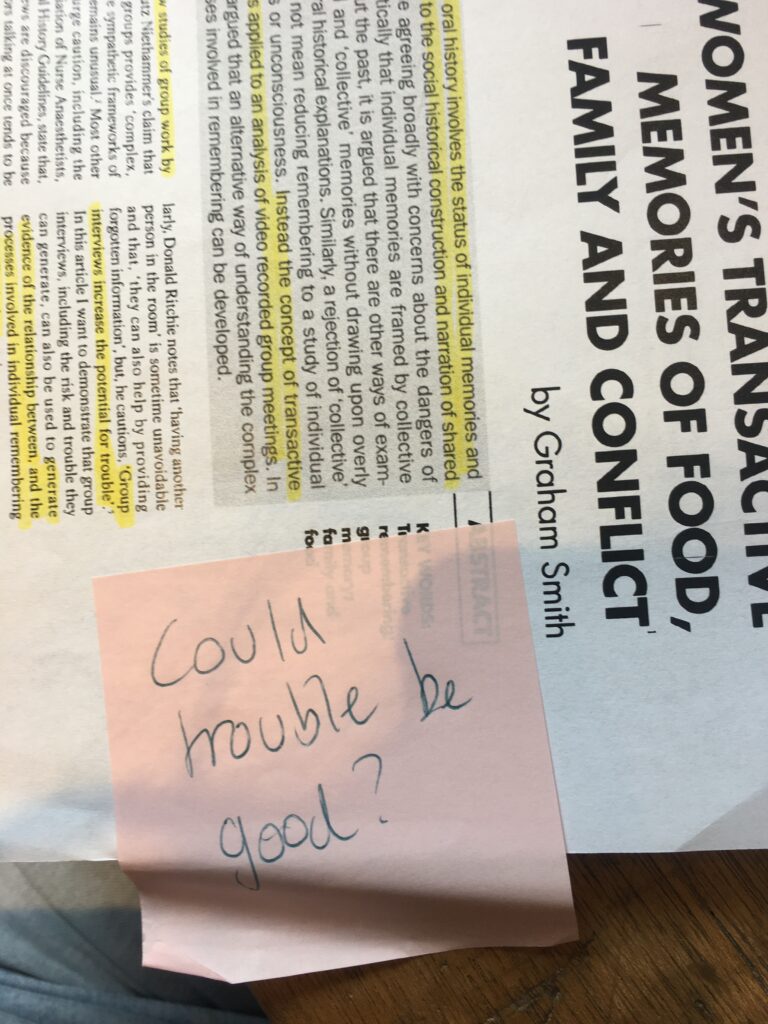

Reuse is not the issue, its about permissions

To reuse an oral history can be very valuable but because everyone views history through a different lens it is likely that the reuser will have different attitude to the creator. This results in different conclusion to be made from the same source. However, oral histories are set up in a way that makes the source only give permission for the creator’s interpretation and not necessarily the reuser’s. This is why it’s not about the reuse of oral histories, we know that creates value, but the permissions around the new interpretation, the one that was not necessarily agreed on by the source.

Even if the source agreed that their recording is open source the reuser might still feel the need to ask for permission especially if that person is still alive.

Recording for reuse

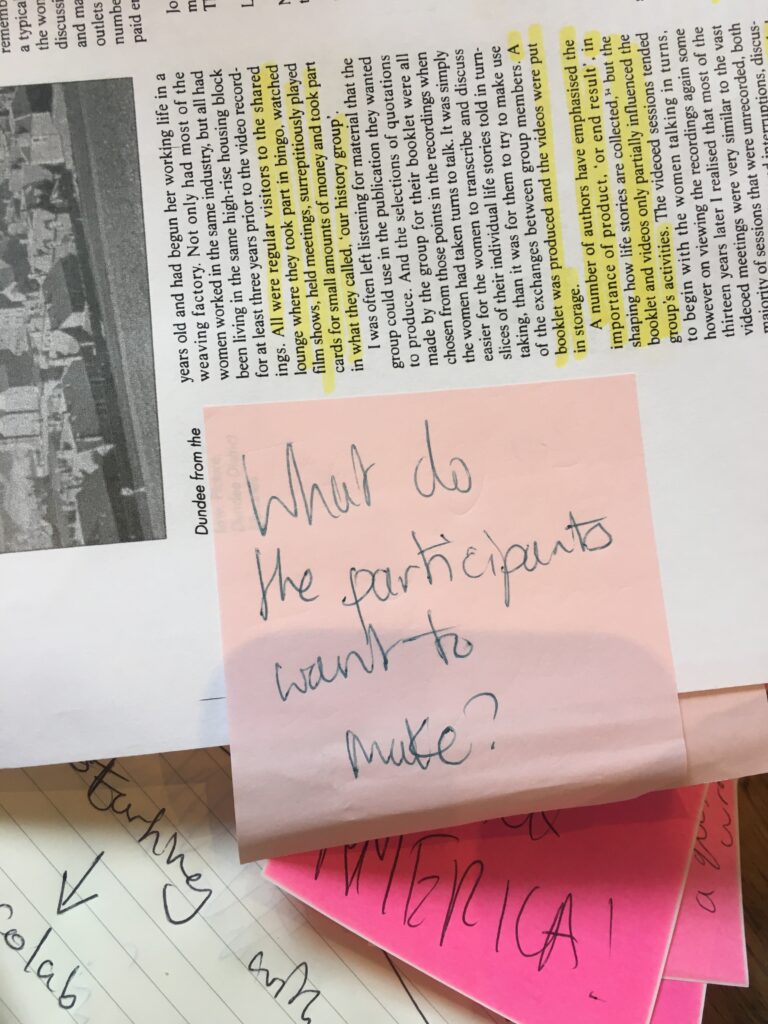

What this reading group made clear to me was that the particular oral histories I will be recording are solely for reuse. I am not planning on writing any analysis on the content of the recordings I just need to make sure that they can be reused properly. Reuse is my mission. I have no lens to work through. (Only the subconscious ones and the large one where I am super focused on getting ALL information.)

Always reflect

This reflection is not only for the interviewer but also for the interviewee. In the piece about food they end with the conclusion that it is important to get the interviewee to reflect on what they are saying. To encourage them to become active participants in their own historical analysis, instead of it solely being the interviewer being the one who is analysing it. This is better for the power dynamic.

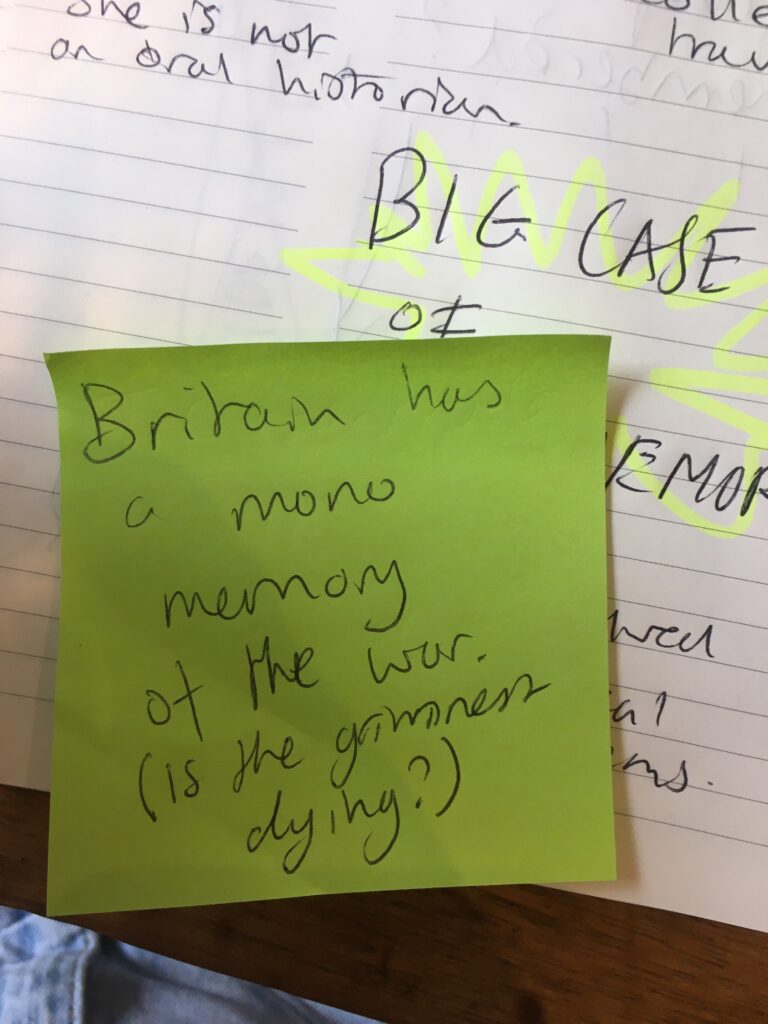

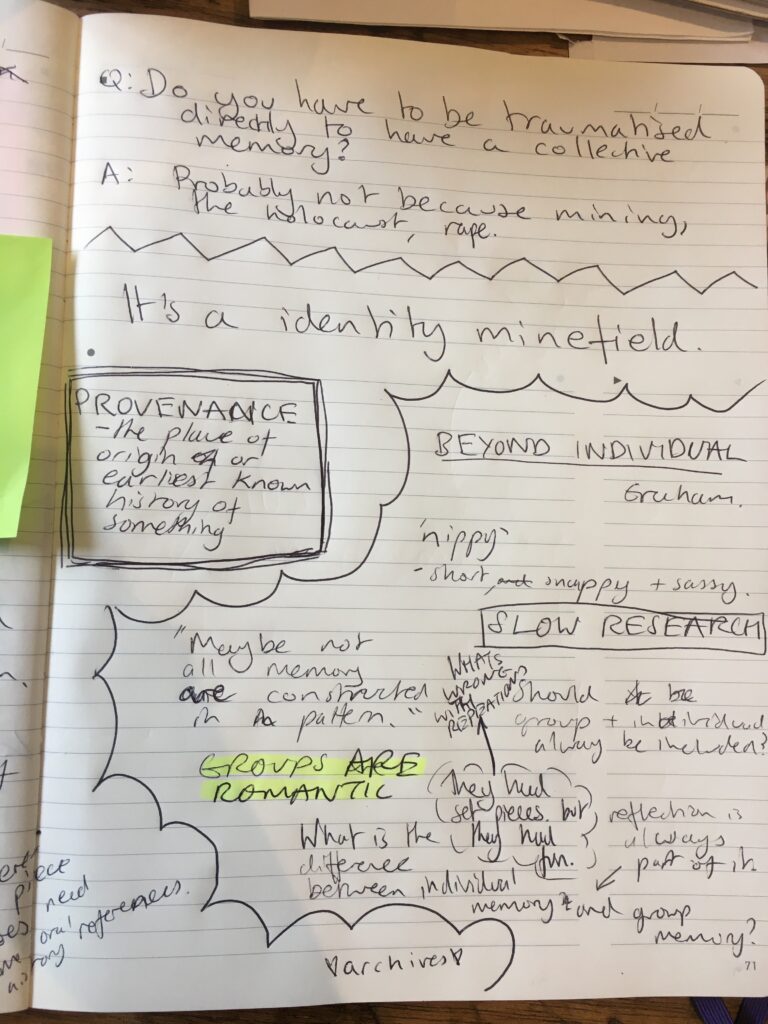

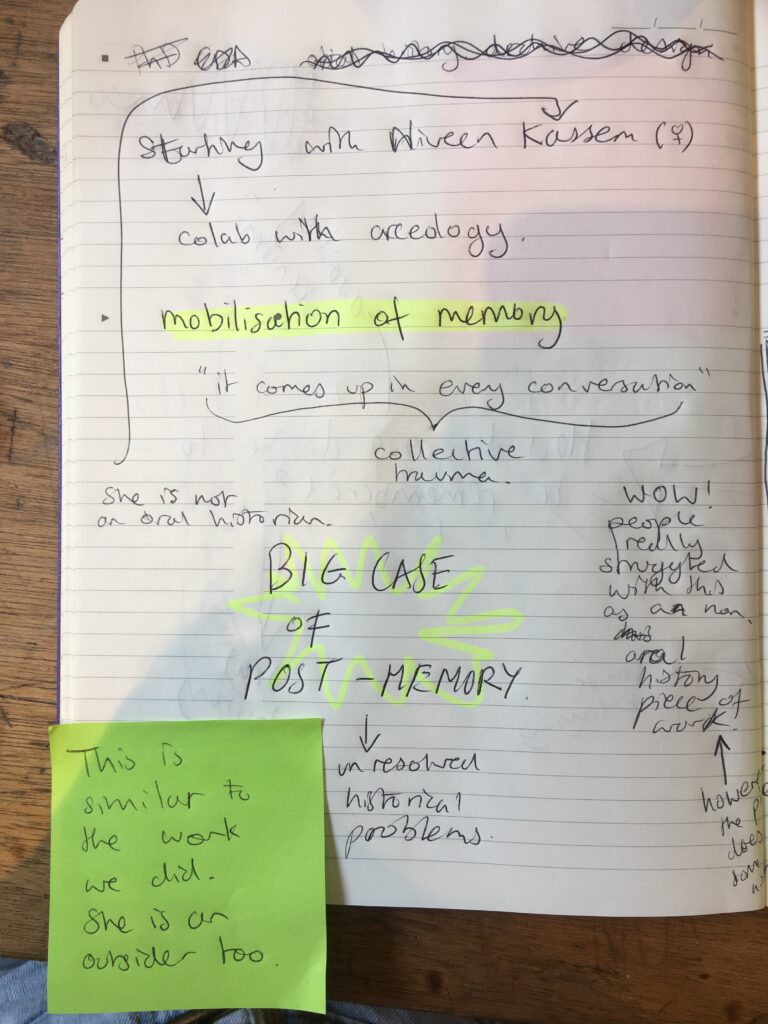

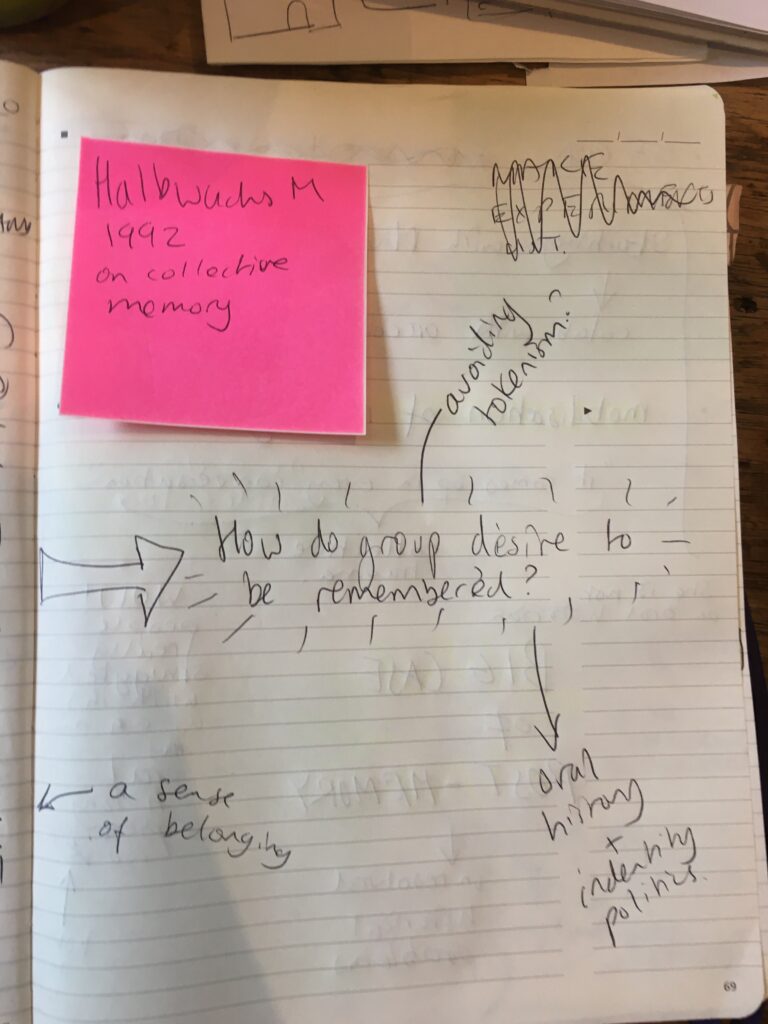

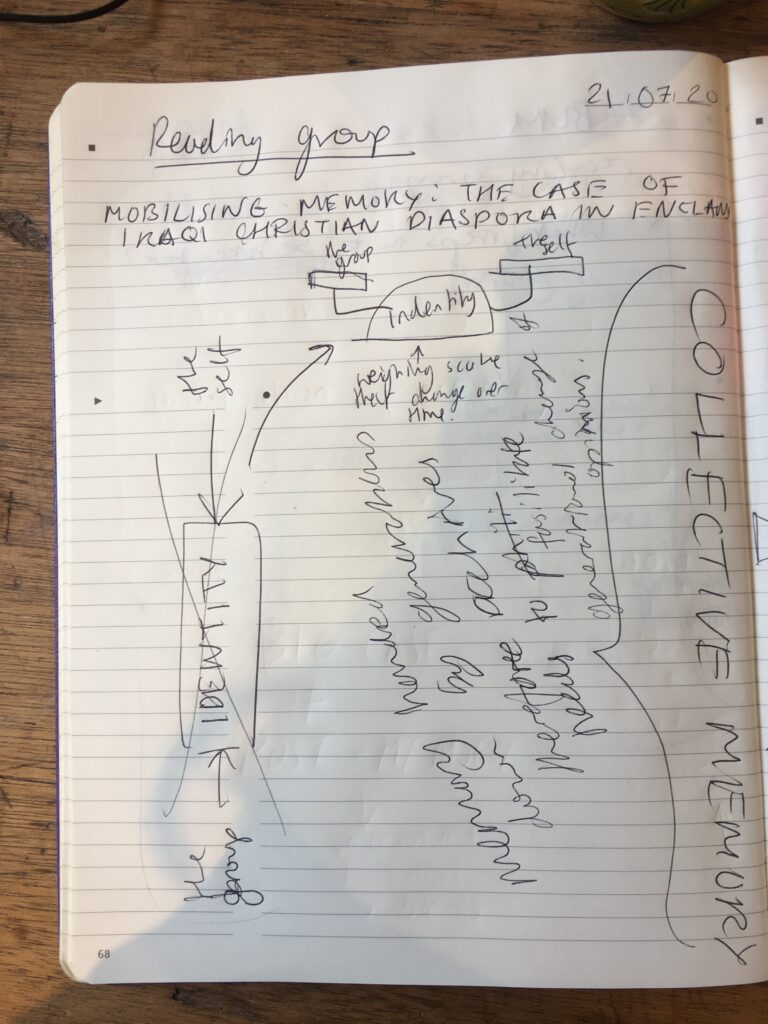

The code

Now I have already started writing a code of practice for the design aspect of this CDA but I have not really thought about what this would be for the oral history side. On reflection the system I am building for this CDA probably should have some type of code that accommodates it. And I believe that a point that was brought up by Graham in the reading group is a good starting. You see he mentioned that on of the oral history collections that was being reused had field notes attached to the recordings that would now be considered very unethical. Now of course these notes are a fabulous source for showing previous scholars attitudes to the method of oral history collection but they probably should not be digitised and on the internet for everyone to find. Graham therefore had them removed from the internet. This made me think that in the process of reusing oral histories there maybe should be the task of also doing ethical checks on the storage. A kind of mutual agreement that all oral historians keep each other in check since ethics is such a nebulous minefield.