Tag Archives: Recordings

OHD_RPT_0256 Options for making oral histories accessible

Tech options for making oral history recordings accessible

V1. January 30 2023

Hannah James Louwerse, Archives at NCBS

Making oral history recordings accessible to people has been infamously difficult, with the oral historian Michael Frisch referring to the issue as “oral history’s deep dark secret”. There have been many attempts to solve this problem with some being more successful than others. By analysing the history of oral history technologies one can see how using technology to access to oral history recordings depends on three factors: maintenance, ethics, and user-friendliness. This short report will go through each of these factors bringing examples of oral history technologies to explain what you should look for when seeking a solution to putting oral history recordings online.

- Maintenance

Maintenance is often the biggest killer of solutions to the deep dark secret of oral history. Maintenance depends on a continuous supply of money and labour, which is not always easy to get hold of, especially within grant cycles. It is therefore essential to think about the maintenance necessary to sustain a technology which allows access to oral history recordings. How you do this depends on the source of the technology and how it was developed.

- Tailor-made, in house development and maintenance

Creating your own digital oral history archiving system allows it to be perfectly tailor to your collections needs. However, it also means the maintenance of this system is solely in your hands, which can be very risky, especially when working within grant cycles. Projects like the Visual Oral/Aural History Archive (VOAHA) created by Sherna Berger Gluck at California State University, Long Beach and Civil Rights Movement in Kentucky Oral History Project Digital Media Database developed by Doug Boyd built tailor-made technologies specifically for their existing oral history collections, either developing the technology themselves or hired someone to do it for them. At the time they were the height of technology, but when the money ran out there was none left to maintain the archives/databases. Both VOAHA and Boyd’s Civil Rights Movement in Kentucky Oral History Project Digital Media Database were “digitally abandoned” and left vulnerable to inevitable technical obsolescence and online hackers (Boyd and Larson, 2014, p. 7; Boyd, 2014, p. 90). In the end the two projects were absorbed by their respective universities’ libraries.

1.2 Use existing specialist oral history software

By using specialist oral history software, the maintenance is no longer your responsibility, which is both a risk and a benefit. The benefit is how it is a cheaper option in comparison to hiring someone full time to take care of the technology. But the risk is that the software developer stops maintaining the software, which is what happen in the case of Stories Matter, an oral history software developed by the Centre of Oral History and Digital Storytelling at Concordia University and a software engineer from Kamicode software (High, 2010; Jessee, Zembrycki, and High, 2011). The Kamicode website still has a page on Stories Matter, but the software is not downloadable. The reason for this is unclear, however it is easy to imagine the maintaining of such niche software is unlikely to be a high priority for a software company.

A more successful example of specialist oral history software is Oral History Metadata Synchronizer (OHMS), developed by Doug Boyd after his reflections on Civil Rights Movement in Kentucky Oral History Project Digital Media Database. OHMS has been in existence for some years and is a popular way for oral history projects and archives to organise their oral history metadata and link the video/audio file to a searchable text. Unlike Stories Matter, OHMS is developed and maintained by people who are interested in oral history and use it for their own projects. Maintaining OHMS is therefore in their own interest.

1.3 Use existing mainstream third party platforms

Another cheaper option is using more mainstream platforms such as Soundcloud or Spotify. These are less niche technologies and therefore do not have the benefits more specialised software has, but the maintenance is pretty much guaranteed since these platforms are universally used. Certain projects have created Spotify playlists and other have Soundcloud versions of their recordings alongside the original files in the brick-and-mortar archive.

- Ethics

The internet is an ethical nightmare and putting someone’s personal story online in an ethical manner is not an easy task. The starting point will always be clear communication to the interviewees on how people will be able to access their recording, and thorough paperwork which accompanies the recording. Following this there are a couple of other things people have done to support the ethical handling of oral history recordings.

2.1 Extracts

The simplest of ethical practices is to only make certain extracts available online. This means you can avoid putting online more sensitive information but still give an example to the archive visitor of the kind of content the oral history holds. If the archive visitor wishes to hear more, they can request the full recording via email. A possible consequence of this might be people only using the online extract and not bother enquiring any further because it is deemed as “too much effort.”

2.2 End user agreement

Archives like Trove and Centre for Brooklyn History have “end user agreements” the archive visitor must agree to before they are allowed access to the oral history recording. These end user agreements contain information on basic copyright and data rights, a disclaimer about the opinions expressed in the recording, and outline the archive user’s obligations. These obligations include correctly citing the recording, adhering copyright law and data protection law. These end user agreements are a way for archives to hold users accountable in case of misuse or rights violations.

- User-friendliness

People have a low tolerance of bad user-experience design. The software Interclipper, championed by Michael Frisch was reviewed during the development of Stories Matter and VOAHA and was deemed difficult to use in both instances (Jessee, Zembrycki, and High, 2011; Gluck, 2014). It no longer exists. OHMS offers both a backend metadata synchronizer and a viewer, the latter however is often left in favour of an in-house interface design. Project Jukebox developed by the University of Alaska in collaboration with Apple Computers Inc. in the 1990s, is still available online but still looks like it was made in the 90s, even though at the time it was described as “a fantastic jump into space age technology” (Lake, 1991, p. 30). It is therefore important the user experience and interface are updated as fashions and taste evolve across the wider internet.

List of examples

- Project Jukebox: https://jukebox.uaf.edu/

- Stories Matter: https://www.kamicode.com/en/portfolio/project/23-concordia-university-stories-matter

- VOAHA: https://csulb-dspace.calstate.edu/handle/10211.3/206609

- Civil Rights Movement in Kentucky Oral History Project Digital Media Database: https://crdl.galileo.usg.edu/collections/crminky/?Welcome

- OHMS: https://www.oralhistoryonline.org/

- Soundcloud: https://soundcloud.com/balticarchive

- Spotify: https://anchor.fm/RainhamHall

- Trove: https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-220064352/listen

- Centre for Brooklyn History: https://oralhistory.brooklynhistory.org/interviews/rivera-dolores-19920911/

Bibliography

Boyd, D.A. (2014) ““I Just Want to Click on It to Listen”: Oral History Archives, Orality, and Usability” in Oral History and Digital Humanities. pp. 77-96. Palgrave Macmillan: New York

Boyd, D.A. and Larson, M. (2014) “Introduction” in Oral History and Digital Humanities. pp. 1-16. Palgrave Macmillan: New York

Gluck, S.B. (2014) “Why do we call it oral history? Refocusing on orality/aurality in the digital age” in Oral History and Digital Humanities. pp. 35-52. Palgrave Macmillan, New York.

High, S. (2010) “Telling stories: A reflection on oral history and new media” in Oral History. 38(1), pp.101-112

Jessee, E., Zembrzycki, S. and High, S. (2011) “Stories Matter: Conceptual challenges in the development of oral history database building software” In Forum: Qualitative Social Research. 12(1)

Lake, G.L. (1991) “Project Jukebox: An Innovative Way to Access and Preserve Oral History Records” in Provenance, Journal of the Society of Georgia Archivists. 9(1), pp.24-41

Smith, S. (Oct 1991) “Project Jukebox: ‘We Are Digitizing Our Oral History Collection… and We’re Including a Database.’” at The Church Conference: Finding Our Way in the Communication Age. pp. 16 – 24. Anchorage, AK

OHD_PRS_0127 Only Time Will Tell: the ethical dilemma of oral histories

This one has been my favourite paper to present so far. I think it was really fun and people seemed to enjoy it.

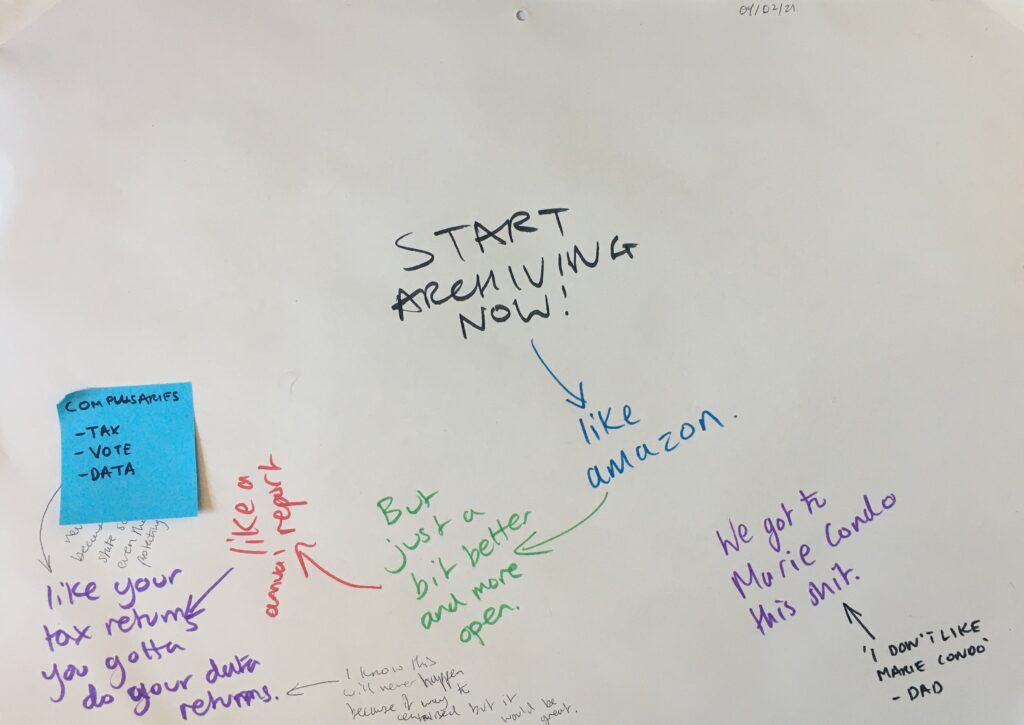

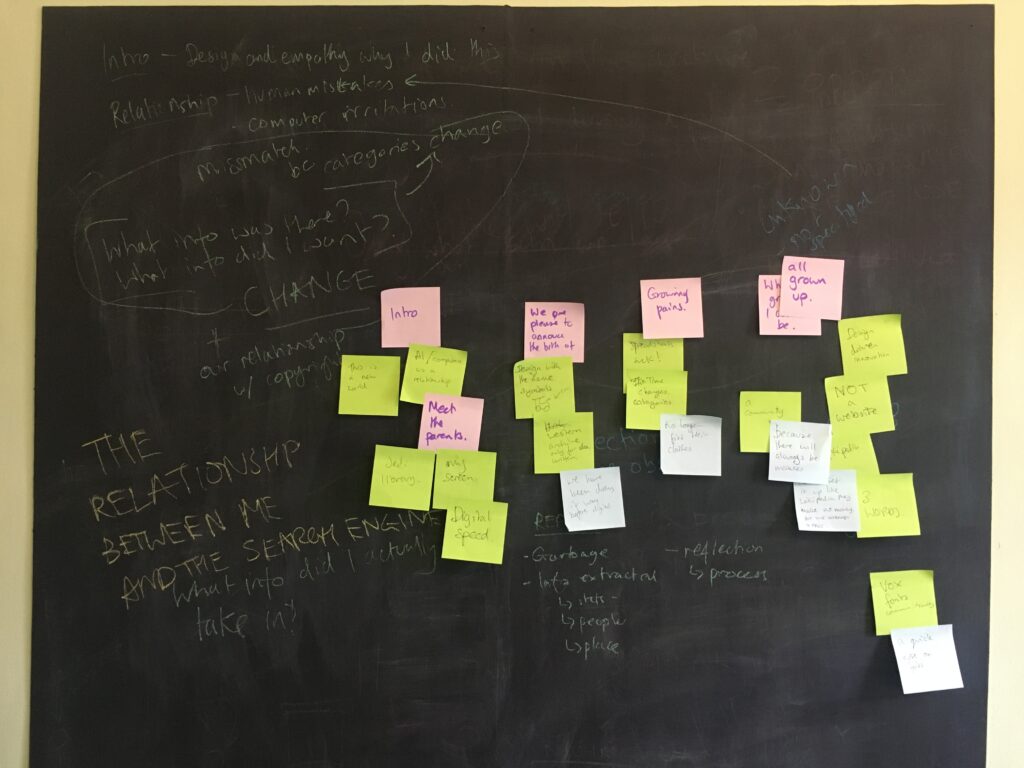

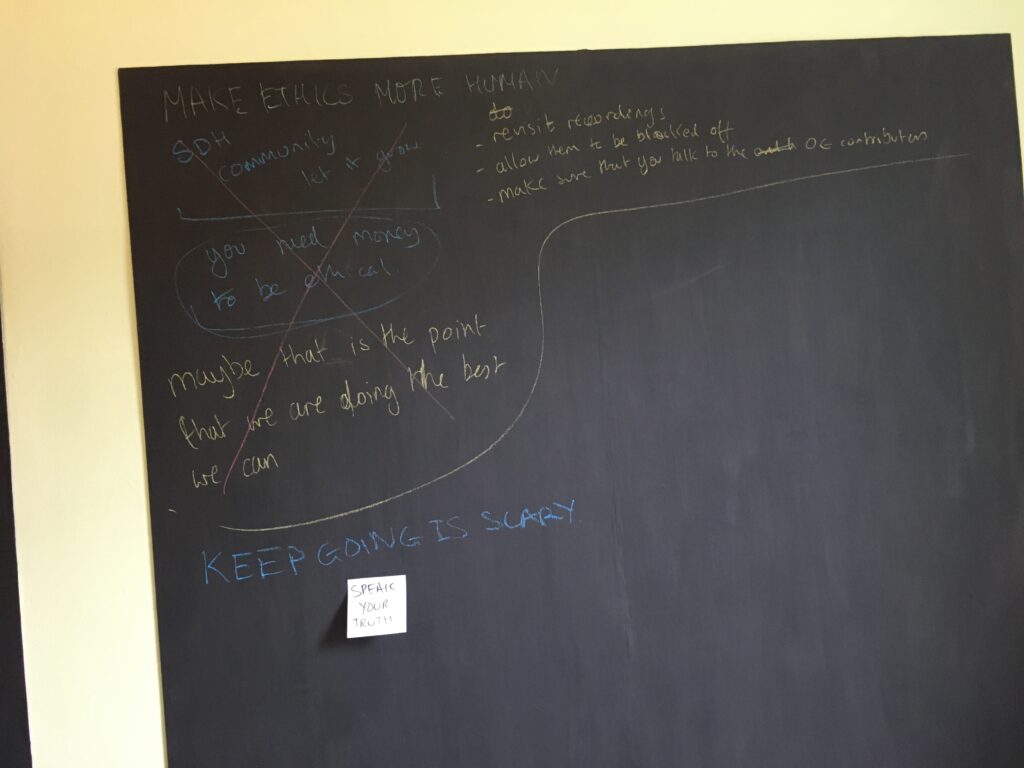

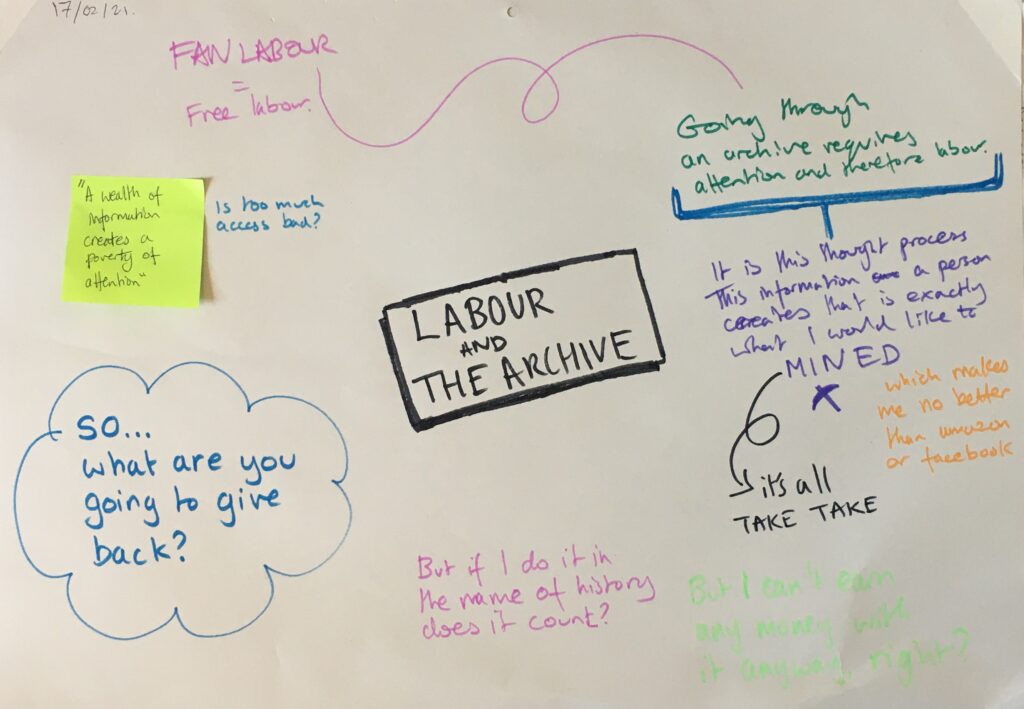

Brainstorming

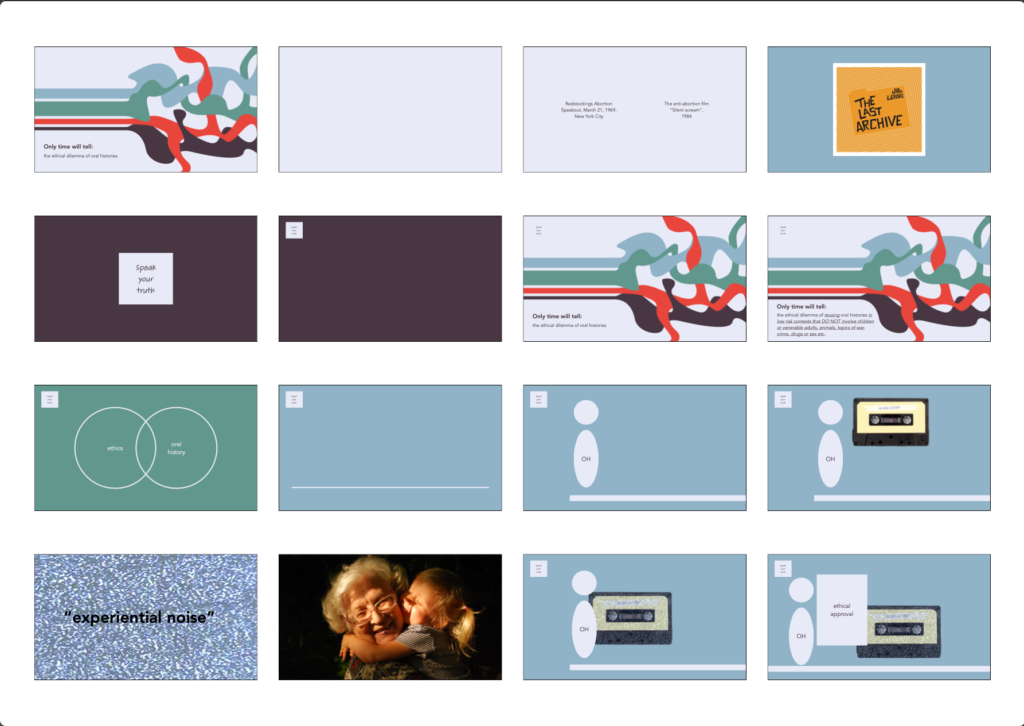

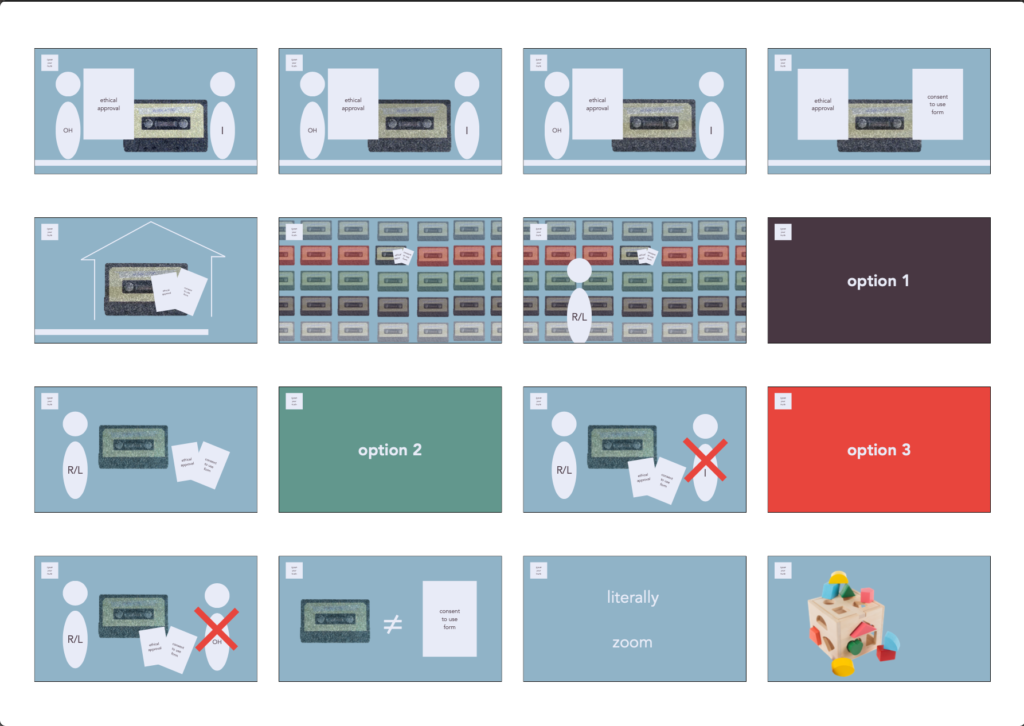

Slides

Script

[slide 1]

I am going play two sound recordings which both discuss abortion, so if you think this might upset you I invite you to mute your computer and after I have played them I will signal in the chat that you can unmute.

(Plays segment from Redstockings Abortion Speakout, March 21, 1969, New York City and the anti-abortion film “Silent scream”)

[slide 2]

The first clip we listened to was from the Redstockings Abortion Speakout, which took place on the 21st March 1969 in New York City. The second clip was from the anti-abortion film “Silent scream” made in 1984.

[slide 3]

Both are featured an episode of the podcast “the Last Archive” made by historian Jill Lepore. In this podcast Lepore is trying to work out who killed truth and in this specific episode she discusses how the concept of “speaking your truth” that was used at the Redstockings’s Speakout contributed to creating the post-truth era we live in now. The whole podcast, but especially this episode haunted me whenever I started writing this paper. I would try to add it in but it did not really work, so in the end I extracted this haunting from my brain by writing

[slide 4]

“speak your truth” on a post-it and popping it in the corner of my blackboard. I am going to do a similar thing now and

[slide 5]

just leave a digital post-it in the corner of my presentation.

[slide 6]

I realised that the title of my presentation is a rather ambitious, so I would like to make some amendments to in order to better frame what I am going to talk about.

[slide 7]

(Only Time Will Tell: the ethical dilemma of reusing oral histories in low risk contexts that DO NOT involve children or venerable adults, animals, topics of war, crime, drugs or sex etc.)

I am specifically looking at how to encourage reusing oral histories and the case study I am basing my research on is the National Trust property Seaton Delaval Hall in Northumberland, which I assume will produce relatively low-risk oral histories.

[slide 8]

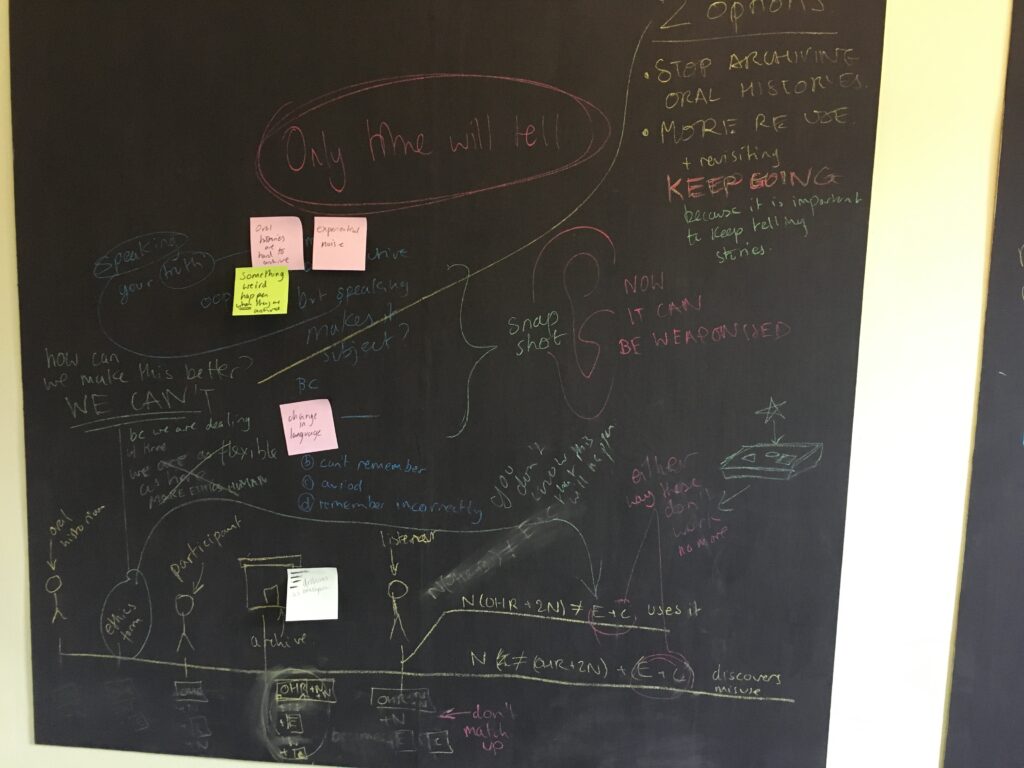

In this presentation I am going to map out the basic relationship between ethics and oral history that I imagine I will experience during these next three years.

[slide 9]

Here we see a timeline of the life of an oral history.

[slide 10]

At the start we have our oral historian, who wishes to conduct an oral history project.

[slide 11]

This is the beginning of the oral history’s life. Already from the start this oral history is affected by something I am going to call

[slide 12]

“experiential noise”. I am using this term to refer to how a person perceives the world at that moment in time, which is influenced by everything from what is in the news to whether they were hugged enough as a child. I specially use the word noise because I find it to be a very nebulous and volatile feeling. Here is a quick example of experiential noise in action.

[slide 13]

This is a picture of someone hugging their grandparent: before the pandemic this would have be a lovely picture of intergenerational love, however now you hope that the grandparent has had both their jabs.

[slide 14]

The oral historian’s experiential noise affects the oral history straight away. Lynn Abrams, refers to this as her “research frame” and discusses in the Transformation of Oral History how her position as a “university lecturer in women’s and gender history” influenced her interviewees testimonies when she did a project on women’s life experiences during the 1950s and 1960s.

[slide 15]

The next step in the life of the oral history is to get ethical approval. How to gain this differs between institutions. I have completed my first ethical approval for my low-risk project and it was relatively painless. I consider myself lucky.

[slide 16]

Clutching its ethical approval the oral history moves on to meet the interviewee, who has plenty of experiential noise.

[slide 17]

The interviewee’s experiential noise is very complicated because they are the ones who are remembering. Memory is messy and potentially all sorts of confabulation, misremembering and gaps can appear during the process.

Now we have all this noise that is being supplied by the interviewer and interviewee, but as soon as the record button is pressed all of it is frozen.

[slide 18]

Stopped. Now we move onto a really important step for my project. The recording can now be archived, which means that it can then be reused and reusing is the thing I am focusing on.

[slide 19]

But we must not forget to consult the consent form, that is the appropriate permissions and clearances, which if I am being honest have no idea of:

- I haven’t done it yet

- It’s different for everyone

- GDPR is confusing

[slide 20]

But let us say for the sake of the story that it has been stored and is available.

[slide 21]

Our little oral history can happily nestle between all the others holding its consent form and ethical approval close to its heart.

[slide 22]

Some time has passed and along comes a researcher/listener. Being a pestilent human means they are full of new fresh experiential noise. Once they and the experiential noise come in contact with the oral history three things can happen:

[slide 23]

Option one:

[slide 24]

The listener listens to the oral history, goes on to write an account of why things changed or stayed the same with a full understanding of the context in which the oral history was created and the experiential noise that was present.

[slide 25]

Option two:

[slide 26]

Because of their experiential noise the listener listens back to the oral history and is shocked by what they hear and goes on to write something about the interviewee that is not flattering. Joanna Bornat recalls a situation where the testimonies of white Australian housewives, who initially had been interviewed about domesticity, were used to illustrate racism in 20th Century. Having their oral histories used in this way was not something the interviewees had agreed to when they gave permission for their oral history to be archived. It also suggests, as did the housewives, that racism has a history. They believed and said things then that they would not believe and say now.

[slide 27]

Option three:

[slide 28]

Again because of their experiential noise the listener listens back to the oral history and is shocked by what they hear because they are surprised that this is allowed to be public. Our relationship with privacy has changed a lot over the last few decades, as has the relationship between researcher and researched. An example of this could be when the historians Peter Jackson, Graham Smith and Sarah Olive, reused the testimonies found in the archive, the Edwardians. Theyfound that the interviewers had included field notes on the interviewees that contained information that definitely would not pass an ethics review or board these days.

[slide 29]

In both option two and three the ethical approval and the consent to use form no longer matched up with the oral history, because the reception of the oral history had changed. The words said have not changed but their meaning has. The passage of time has not just changed the experiential noise of the listener/researcher but the whole of society’s. This is not surprising as language changes all the time, just think of the word

[slide 30]

literally or zoom.

This is why oral histories are so difficult to archive and write ethics for.

[slide 31]

The best way I can describe it is like one of those toys where you have to put right shape through the right hole.

[slide 32]

Only in the case of oral histories the shape keeps changing.

So what do we do now?

Well I offer three options:

[slide 33]

Option one:

[slide 34]

Stop recording oral histories, stop archiving them, stop asking money for them. It’s just going to be an ethical mess. Stop it.

Now I am going to go on a whim here and assume this probably is not what people are looking for.

[slide 35]

Option two:

[slide 36]

We can try and improve our ethics forms to accommodate its noisy nature. Maybe if we make a system that forces us to annually update our ethics and consent forms we can keep up with the noise. Now considering how much time and effort already goes into ethics I imagine that this option is also not realistic. It reminds me of Wendy Rickard writing in her paper Oral history – ‘more dangerous than therapy’ that she wishes that more interviewees and interviewers could listen back to their tapes, but that this is simple not possible due to lack of resources – “it seems you have to be rich to be ethical”.

[slide 37]

Option three:

[slide 38]

To start with we do more reusing. According to Michael Frisch within oral history there is a preference to record interviews instead of reuse them. This results in less information on the process of reusing. Which is why I am suggesting that we reuse more so we can learn more about it. The more we revisit, the more we can reflect, the faster we can pick up on ethical misdemeanours or challenges and the more we can improve the process of recording, archiving and reusing oral histories. We need to become more practiced in reusing and learn more about the ethical pitfalls of reuse. It is important to keep telling these histories that people have worked hard for to capture, but this also means we need to keep the shop tidy. Sometimes we might make a mistake but then it is our responsibility as a community to fix it and grow.

[slide 39]

We are never going to be able to write the perfect ethics form. Time affects how we experience oral history so we need to find something that is as stubborn and relentless as time which I believe is

[slide 40]

us (the human race)—the vessels of experiential noise and the deciders of

[slide 41]

“what is ethical?”.

[slide 42]

Like our history, our ethics change with us because it lives within us, so trying to shove all the nebulous responsibility onto a single static document does not make sense. So for now we might just have to hustle though because only time will tell if we are doing it right.

[slide 43]

But there is one more thing…

[slide 44]

The post-it note. “Speak your truth”.

So after I had finished planing this paper, I stared at the post-it note for while contemplating its existence. Eventually I concluded that the option three, where we embrace reusing and all its messiness was really scary. In this post-truth world where everyone “speaks their truth” and does not listen to each other it is terrifying to simple get on with and keep going. As an oral historian you could ruin someone’s life because you allowed public access to their testimony and someone completely misused it. You could write something and be “cancelled” or “trolled” for your opinions. Or you can have your funding cut by your government because the narrative your telling is not what they want to hear.

[slide 45]

Initially I was going to end it here in a slightly depressing way, but I sent my draft to my supervisor who said that I might be over-worrying a little bit. His words reminded me of something my old neighbour used to say, something that I think is important when you do pretty much anything in live including research:

[slide 46]

“all perfect must go to Allah so if you want to keep your rug you have to make a little mistake”

OHD_BLG_0075 Texts, Images and Sounds Seminars Summary

What follows is a summary of the various seminars that I took presented by Ian Biddle from Newcastle University. Overall I enjoyed these seminars mostly because I had covered many of the topics during my time at Goldsmiths but now I understand it better.

Thinking Texts

Seminar

You can read many things as texts: buildings, art, music etc. The word text comes from the word to weave. A text therefore represents a complicated set of ideas woven together to create one idea.

There is a lot of snobbery and hierarchical thinking around text and the author. Author come from the word authority. However to say that the author has complete authority over a text is a very outdated idea. Everyone interprets and experiences texts in a different way. This is often due to the various elements that make up their background: gender, race, work, economical background etc. In addition to this snobbery around interpretation there is also the also now outdated belief that cultures that have no text, have not published, have no history. Which is a bit racist.

Visual Culture and the Cinema Mode of Production

Reading and Seminar

I wrote a summary in a blog post

Map

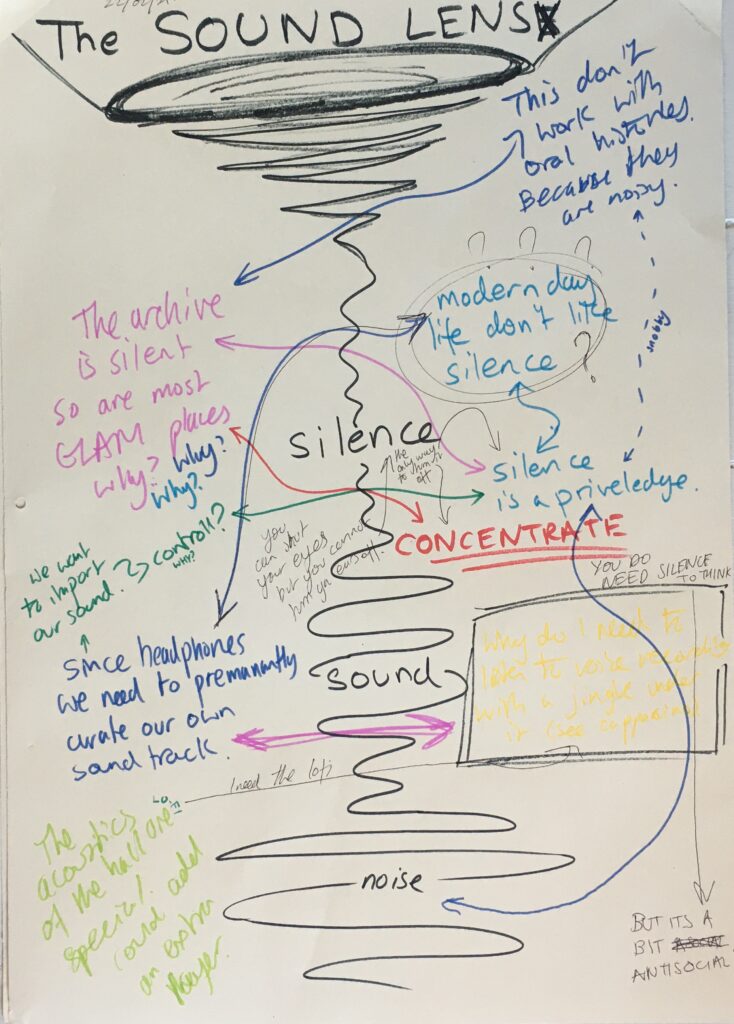

Noise Cultures Base/Bass Materialism

Seminar

Sound is married and dependant on technology. They way we experience sounds has developed in correlation with tech look at the invention of noise canceling headphones but also the noise of industry and cars that infiltrates our everyday surroundings. Because of advancements in speakers listening has become a contact sense. We can now feel the beat of the music move our bones to the rhythm.

There is a spectrum of sound where music is on one end and noise is on the other. Where sounds fall on this spectrum changes with time and whoever is listening.

How we perceive sound and our experience of it has changed dramatically over time. We now live in a world of lo-fi sound, a constant blurry noise where we cannot make out the specific sources. Before we live in hi-fi sound. Everything could be heard crystal clear because we did not have the rumble of the machines.

Our relationship with silence is also very strange. Sound proof housing in a city centre is extremely expensive. To have access to silence is a privilege. Yet we are also afraid of silence. We are constantly turning on music and TV. Most people cannot walk from A to B without having headphones in. I think we have a need to control our sound.

Slavonic Languages have different words for listening but I haven’t been able to find any examples.

‘Acousmatic Sound’ listening to a sound without know the source. Basically Greek philosophers would stand behind a curtain and speak in an effort to get the audience to concentrate better on what they were saying.

Map

The Affective Turn or the New Scholarship of the Senses

Seminar

Affect (psychology) = mood

Affect (philosophy) = the grammar of emotions

Affect labour = labour that is conducted in the service industry often considered feminine work

Affective computing = instead of the old input output model this type of computing is focused on interface

Feeling works on a very different logic. It’s the body of knowledge outside of the rational that controls emotions. It is in a sense a different world that we live in.

Affect. Complicated political thinking without attracting too much attention or a specific type of attention from a suppressive state. Think Provo and their ludike actions.

Art organises your feelings. It’s that ah! moment when you see a work of art that perfectly communicates a complex feelings.

Affect theory kills boundaries. Biddle’s tip if you are stuck throw some affect theory at it. It’s not political and it unpicks the logic of other theories.

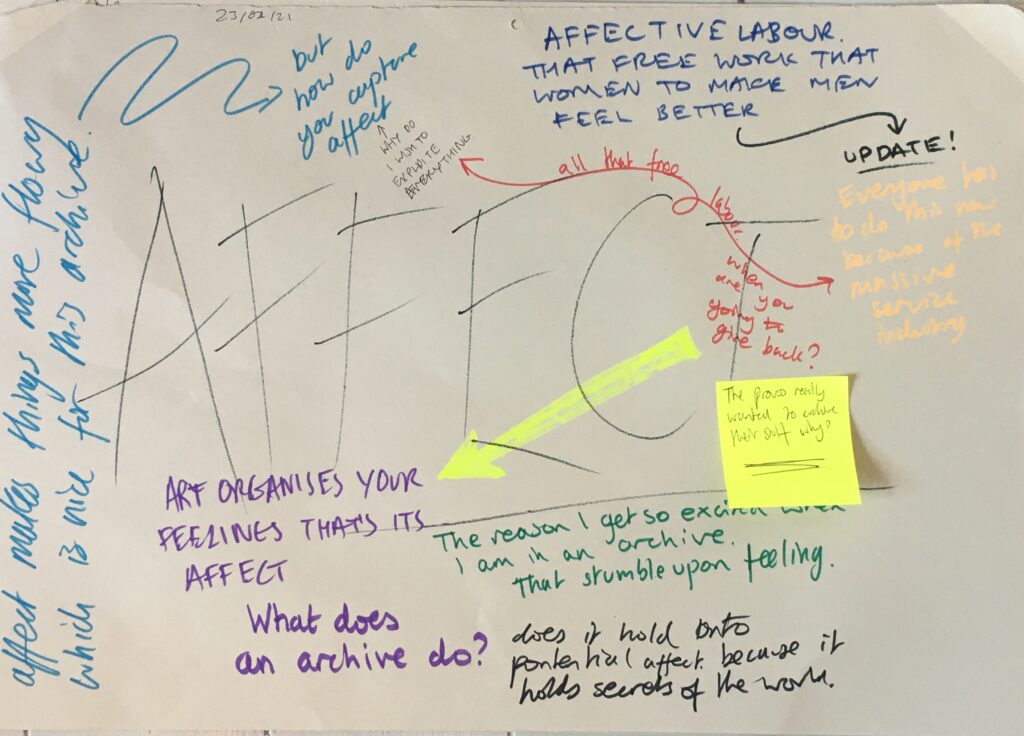

Map

Memory and the Archive

Reading

This is an easier version of Derrida.

To make an archive is to repeat. It is a deeply nostalgic act with questionable productivity. “I just want to relive it”

The archive represents the now of whatever kind of power is being exercised anywhere at any place or time.

There is a feverish desire – a kind of sickness unto death – that Derrida indicated, for the archive: the fever not so much to enter it and use it, as to have it, or just for it to be there, in the first place.

Stedman, Dust

We have to have all the data.

And currently those who are in power (big tech) are also mining all the data for reasons no one is completely sure about less of all them.

Seminar

Archives are full of metaphors. From the architecture of the buildings that store them to the icons we use to store data on our laptop. This is common theme in new technologies. The first cars looks like carriages and the save button is a floppy disc. However some of these metaphors are more tailored to the elite, as in the elite are more likely to recognise this metaphor or the metaphor represents an elite version. Just look at the representation of the Jedi library in Star Wars it is nearly exactly the same as the library at Trinity College in Dublin. Why would Jedis need books?

The putting something in an archive is called archivisation. By archiving something you move it from the private into the public but not from the secret to the non-secret. That is because archives promise access but do not always give it. An archive can be compared to house arrest, the documents are not in prison but they are also not free.

Archives are particular anxious places. They worry a lot about the longevity of their collections and general rot. There is also the added anxiety that new forms of preservation leads to new forms of loss. When we were able to record sound we had to learn how to archive it. I cannot imagine the amount of loss that is created by the internet.

Quick warning here to not fetishise the archive please.

Map