People with Type 1 diabetes (T1D) have a pancreas that no longer secrets enough insulin, so from diagnosis they are dependent on insulin being administered in either an injection or via an insulin pump. This means people must manually balance and adjust their insulin medication according to their meals, while also accounting for what the sugar concentration in the blood is. Unfortunately, life can be a daily battle and tightrope walk to keep their blood sugar in the healthy range and preventing it from going too high (damages blood vessels, eyes, kidneys, nerves), or too low, which can be dangerous for the brain’s energy supply.

Exercise can be a dilemma for people with Type 1 diabetes

In general, people with T1D are encouraged to be physically active due to the associated health benefits (e.g. better heart and lung system), and in general the disease doesn’t hold people back, with thousands running marathons yearly, there is a T1D professional cycling team, there are stars like Henry Slade and Sir Steve Redgrave who reached the pinnacle of their sports (Figure 1). However, for many people exercise is avoided due to worries of their diabetes control deteriorating, or exercise causing dangerously low blood sugar, termed hypoglycaemia (fuel to the brain is compromised). Hypoglycaemia can be fatal if not treated, and the more frequent this event occurs, the more accustomed the body becomes to it and the usual feelings we get when the brains sugar is getting too low (pale, hunger, pins and needles, confusion), don’t occur. This results in a dangerous situation where brain fuel is compromised, but the defence symptoms against it are blunted. Naturally, exercise potentially leading to increased occurrence of hypoglycemia is an understandable barrier.

Figure 1: Type 1 diabetes athletes. Professional cycling team Team Novo Nordisk and England Rugby union international, Henry Slade.

“If I exercise my diabetes gets worse” versus “exercise is no problem for me”

For decades, in clinic observations have reported a wide range in how people cope with frequent exercise with clinicians observing improvements in some and a deterioration of diabetes control in others. Indeed, some clinical colleagues remained sceptical on recommending people engaged in exercise at all, such was the risk that their diabetes control would worsen. Over the past 10 years our group has sought to understand why this is, with the aim that more targeted and personalised support can be created for the individual.

Are the insulin producing cells in the pancreas truly destroyed?

It has been recently shown that while people are dependent on insulin as medication, the pancreas may have an underlying and persistent ability to produce small amounts of insulin still. This is important, because any remaining pancreas function could play a role in how the person walks that tight rope when exercising.

We recently conducted a study where we measured how much ‘C-peptide’ people were secreting in their blood and urine in response to food. C-peptide is released from the pancreas along with insulin and is used to assess how much function or damage is present in the pancreas. We found that in people with established Type 1 diabetes (>5 years), that there was a wide range in how much C-peptide people produced. Some had zero levels of C-peptide, while others had very small amounts and a small fraction of people were still producing a significant amount. We then took these groups of people and got them to walk on an incline treadmill for 45 minutes and monitored their blood sugar for a couple of days after exercise. We found in those with no C-peptide their diabetes control got worse, while in those who were positive, their diabetes control improved. So, despite having the disease similar amounts of time, being of similar fitness, and similar overall diabetes control, a controlled bout of exercise resulted in a divergent split in their blood sugar control; those with C-peptide improving, and those negative, getting worse (1, 2).

Age at diagnosis as an indirect measure of pancreas function

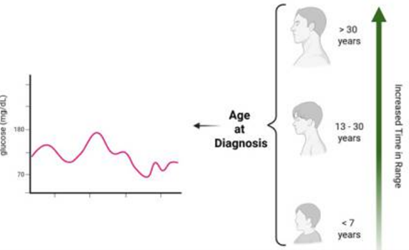

We sought to understand the exercise tightrope further by looking at how the age at someone’s T1D diagnosis might impact their blood sugar control when exercising. Analysing insulin producing cells from pancreas donors shows that the damage in the pancreas seems to be different depending on when they were diagnosed, early childhood versus teenage versus adulthood. We explored how splitting people by these diagnosis-age categories impacted their diabetes control. We showed that those diagnosed before the age of 13 had worse diabetes control when exercising, and those with adulthood diagnosis had better blood sugar when exercising (Figure 2). Put simply, two people of the same fitness, overall diabetes control, and the same duration of diabetes, but one diagnosed as a toddler versus one diagnosed in adulthood, could have divergent changes in their diabetes control when doing the same bout of exercise (3).

Figure 2: Adapted from Taylor et al. (3) – Age at Type 1 diabetes diagnosis versus time in normal blood glucose range.

What does this mean for the exercise tightrope?

We hope our data will provide evidence to clinicians to monitor every person’s C-peptide levels, regardless of how long they have had T1D. This could provide useful information in identifying people at risk of finding exercise hard, it could also mean pushing others to more challenging diabetes control targets. There are also tools like diabetes technology, blood sugar sensors, and exercise education programmes that could be used in a more targeted way to support people to exercise without compromising their diabetes control. At a personal level, people can suffer from a lot of anxiety and distress because of how hard they find managing their diabetes, while others find things easier. If the clinical team are aware that there could be some underlying disease differences that explain this – ultimately, this will improve the persons understanding of their own disease, and potentially make safe exercise, with targeted support, adoptable into the lives of all people with Type 1 diabetes.

References

- Taylor GS., Shaw, AC., Smith, K., Wason, J., McDonald, TJ., Oram, RA., Stevenson, E., Shaw, JAM., West, DJ. (2020). Capturing the real-world benefit of residual beta-cell function during clinically important time-periods in established type 1 diabetes. Diabetic Medicine, 39:e14814

- Taylor, GS., Smith, K., Capper, TE., Scragg, JH., Bashir, A., Flatt, A., Stevenson, EJ., McDonald, TJ., Oram, RA., Shaw, JA. & West, DJ. (2020). Post-exercise glycemic control in type 1 diabetes is associated with residual β-cell function. Diabetes Care, 43(10), 2362-2370.

- Taylor, GS., Bruger, B., Scragg, JH., Page, O., Schmid, H., Nsengimana, J., West, DJ. & Shaw, JA. (2025). Impact of Age at diagnosis and insulin delivery modality on free-living glycemia in Type 1 diabetes during periods associated with dysglycemia: a retrospective analysis of the type 1 diabetes exercise initiative study. Diabetes Technology & Therapeutics, in press.