By Kirstie Cronin

Me, the foodie.

I have always adored food. My parents dubbed me a “foodie” long before I knew what that meant. Trying new foods, cuisines, and ingredients genuinely feeds my soul (pardon the pun) and brings me so much joy. Throughout my studies, cooking after a long library day, whether for myself, friends, or my boyfriend, became my favourite ritual. Those that know me well know that I find cooking extremely therapeutic, it allows me to switch off after a long day and delve into herbs, spices, and new recipes. And yes, hands up, I love snapping an aesthetically pleasing picture of my creations.

I studied and graduated with an MSci degree in Neuroscience from the University of Glasgow and developed a particular passion for population brain health and dementia prevention. I conducted a year-long placement investigating the lifelong risk of dementia in former professional rugby players, as well as contributing to a study investigating the impact of modifiable risk factors for dementia in a cohort of former professional football players.

Following graduation, I worked as a research technician using post-mortem diagnostic techniques to examine the pathological impact of traumatic brain injury on neurodegenerative diseases.

My opponent, Dementia.

I moved to Newcastle to begin my role as a Research Assistant within HNERC, leading the analysis for an Alzheimer’s Research UK-funded project exploring how healthy eating patterns in the UK influence dementia risk.

Briefly, dementia is a disease of the brain that leads to cognitive decline affecting memory, thinking, and everyday functioning. Around 57 million people currently live with dementia worldwide, and this number is expected to rise to ~153 million by 2050. With roughly 10 million new cases each year, the need for action is urgent.

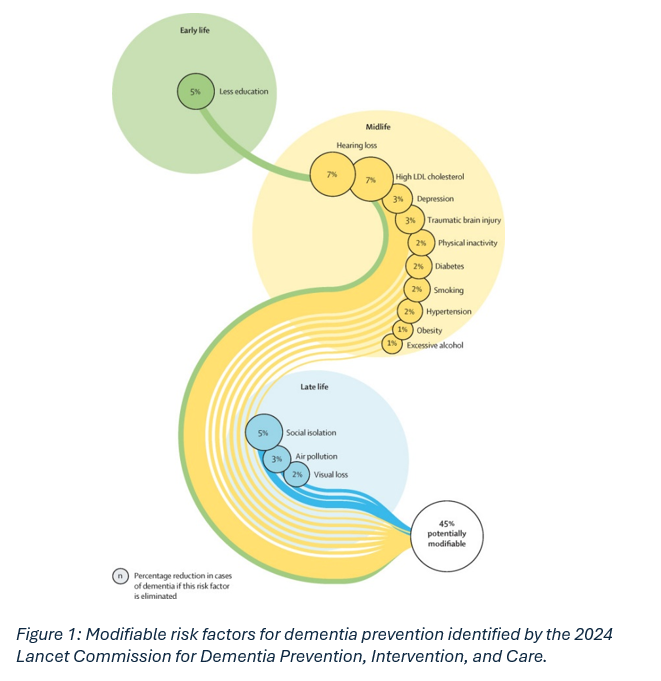

Identifying risk factors for dementia that the population can actively address is essential for disease prevention. Evidence from the 2024 Lancet Commission for Dementia Prevention, Intervention, and Care shows that around 45% of dementia cases could be preventable by addressing modifiable risk factors (Figure 1). Diet is one such risk factor that not only directly, but also indirectly through conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, and obesity, influences dementia risk.

So, what does a brain‑healthy diet look like in the UK?

Most people have heard of the Mediterranean diet. It is widely considered a gold standard dietary pattern for promoting overall and brain health. It emphasises intake of fruits, vegetables, seafood, olive oil, legumes, nuts, and a preference for white over red meat, while limiting sweets, pastries, red meat, and butter, margarine, or cream. Research shows that people who follow this diet tend to have a lower risk of dementia.

However, the Mediterranean diet doesn’t really reflect a typical UK diet. Ingredients can be less accessible or more expensive, and studies show that the Mediterranean diet may actually have weaker associations with health outcomes when applied outside Mediterranean populations.

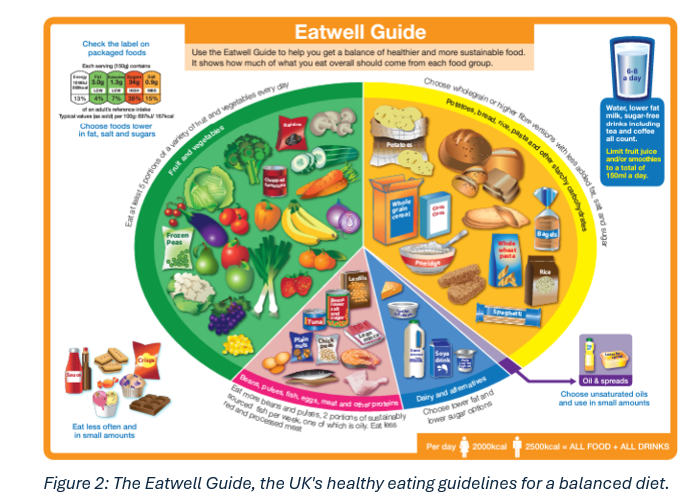

This is where the UK’s own healthy eating model, the Eatwell Guide, comes in (Figure 2). The Eatwell Guide is depicted in a plate‑style diagram showing what a balanced diet looks like based on UK food culture. Like the Mediterranean diet, it encourages a high intake of fruits and vegetables, lean protein sources like seafood and chicken, and limits red/processed meat and high‑fat foods. The Eatwell Guide also promotes consumption of starchy carbohydrates, especially wholegrains, reflecting common UK foods.

Fighting dementia with food.

My team and I are investigating how adherence to the Eatwell Guide may influence dementia risk using the Biobank cohort of over 500,000 participants. Over the past few months, I have been creating dietary scores to measure how closely participants follow the Eatwell Guide. Using these scores, I will then explore whether greater adherence is associated with lower dementia risk, including specific subtypes like Alzheimer’s disease. I will also look at whether the diet–dementia relationship differs across population sub-groups and whether any specific foods or food groups stand out as especially protective.

What Can You Do?

Even if you think you eat “pretty well,” there is always room to improve. When I reflected on my own diet and eating habits, I was surprised by how many easy changes I could make to improve my nutrient intake and in turn improve my overall and brain health.

This project has allowed me to bring my research straight into my kitchen. I have had the joy of creating Eatwell‑aligned recipes to share with our PPI group and discovering new ways to cook the food I already love. I look forward to sharing exciting updates and possibly some new recipes, as this project progresses.

References

Griffiths, A., Malcomson, F., Matu, J., Gregory, S., Fairley, A. M., Townsend, R. F., Jennings, A., Ward, N. A., Ells, L., Stevenson, E., & Shannon, O. M. (2025). Socio-demographic variation in adherence to The Eatwell Guide within the UK Biobank prospective cohort study. https://doi.org/10.1101/2025.06.06.25329110

Livingston, G., Huntley, J., Liu, K. Y., Costafreda, S. G., Selbæk, G., Alladi, S., Ames, D., Banerjee, S., Burns, A., Brayne, C., Fox, N. C., Ferri, C. P., Gitlin, L. N., Howard, R., Kales, H. C., Kivimäki, M., Larson, E. B., Nakasujja, N., Rockwood, K., … Mukadam, N. (2024). Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2024 report of the Lancet standing Commission. In The Lancet (Vol. 404, Number 10452, pp. 572–628). Elsevier B.V. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(24)01296-0

Shannon, O. M., Ranson, J. M., Gregory, S., Macpherson, H., Milte, C., Lentjes, M., Mulligan, A., McEvoy, C., Griffiths, A., Matu, J., Hill, T. R., Adamson, A., Siervo, M., Minihane, A. M., Muniz-Tererra, G., Ritchie, C., Mathers, J. C., Llewellyn, D. J., & Stevenson, E. (2023). Mediterranean diet adherence is associated with lower dementia risk, independent of genetic predisposition: findings from the UK Biobank prospective cohort study. BMC Medicine, 21(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-023-02772-3

Stewart, W., Russell, E. R., Lyall, D. M., Mackay, D. F., Cronin, K., Stewart, K., Maclean, J. A., & Pell, J. P. (2024). Health and Lifestyle Factors and Dementia Risk among Former Professional Soccer Players. JAMA Network Open, 7(12). https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.49742