倫理、ヘルスケア、および人工知能に関する学習教材

© 2024, Jan Deckers and Eisuke Nakazawa

Preliminary note / はじめに

This learning resource was developed by Jan Deckers with advice from Eisuke Nakazawa, who wrote the Japanese translation. The Great Britain Sasakawa Foundation provided the funding. This learning material was developed primarily to help students, particularly those in various health care disciplines, to think through some of the moral dilemmas associated with the use of artificial intelligence (AI) in health care. It may appeal also to many other students and scholars. You can work through this resource at your own pace. It may take you around 3 hrs to do this. The text is interspersed with moments of reflection where you might like to pause and think for a while, before moving on.

この学習リソースは、日本語訳を書いたEisuke Nakazawaのアドバイスを受けてJan Deckersによって開発されました。グレイトブリテン・ササカワ財団が資金を提供した。この学習教材は、特にヘルスケア分野の学生が、人工知能(AI)の使用に関連する倫理的なジレンマを考察できるよう支援するために開発されました。また、多くの他分野の学生や研究者にとっても興味深い内容となる可能性があります。この教材は、自分のペースで学ぶことができますが、すべての内容を通読するには約3時間かかると見積もられます。教材中には、考える時間を設けるための「考察の時間」が挟まれています。進む前にひと息ついて考えてみてください。

1. Objectives / 目的

This learning resource has been developed to stimulate ethical discussion of how health care might be improved and undermined by the development of artificial intelligence (AI) and how AI systems ought to be designed and used to promote health care. While recognising that all biological organisms have interests in health, the focus here is primarily on human health care.

この学習教材は、AIの開発がどのようにヘルスケアを改善し、あるいは損なう可能性があるか、またAIシステムをどのように設計・使用するべきかについて倫理的議論を喚起することを目的としています。本教材は、およそ生物であれば自分の健康に関心を持っていることを認識しつつも、主に人間のヘルスケアに焦点を当てています。

The following questions will be discussed:

- How to ensure that AI for health care is evidence-based?

- How to navigate the black box of AI?

- How to use AI data responsibly?

- What are the ethical issues related to the use of carebots?

- Is the use of AI for health care sustainable?

- Does AI change human self-understandings or identities, and does it do so for better and/or for worse?

- Do people produce conscious entities when they create AI systems?

この教材では、以下の問を考えていきます。

- ヘルスケア向けAIがエビデンスに基づいていることをどのように保証するか?

- AIのブラックボックス問題にどう対処するか?

- AIデータをどのように責任を持って使用するか?

- ケアボット(介護ロボット)の使用に関する倫理的問題は何か?

- ヘルスケア向けAIの使用は持続可能か?

- AIは人間の自己認識やアイデンティティをどのように変えるのか、そしてそれは良い変化なのか悪い変化なのか?

- AIシステムを作成する際、人々は意識を持つ存在を生み出しているのか?

2. How to ensure that AI for health care is evidence-based? / ヘルスケア向けAIがエビデンスに基づいていることをどのように保証するか?

Those who design AI systems for health care should use evidence to develop such systems, but they may not be willing to do so. While disease prevention and health promotion should, arguably, be guiding the development of AI in health care, AI designers are not always motivated primarily by these goals due to the existence of conflicts of interests.

ヘルスケア向けAIシステムを設計する者は、そうしたシステムを開発する際にエビデンスを使用するべきです。しかし、彼らが必ずしもそのようにするとは限りません。本来であれば、疾病予防や健康促進がヘルスケアAIの開発を導くべきですが、利益相反が存在するため、AI設計者たちがこれらの目標だけを動機にしているとは限りません。

Reflection:

Reflect for a moment on what sorts of conflicts of interests might drive the development of AI systems for health care?

考察の時間

ヘルスケア向けAIシステムの開発を動機づける可能性のある利益相反には、どのようなものがあると思いますか?

Image 1: CC BY-SA 3.0; Conflict Of Interest by Nick Youngson; Alpha Stock Images; https://www.picpedia.org/keyboard/c/conflict-of-interest.html

Companies that design AI systems for health care know that they should take some interest in health as their systems would be highly unlikely to be used if they undermined health. However, they might be designed to promote the health of some at the cost of that of others. For example, by being designed in such ways that users are likely to buy particular products, the financial interests of (sponsors of) AI companies might be advanced significantly. These financial benefits might promote them, at the expense of many others (Strickland 2019).

企業がヘルスケア向けAIシステムを設計する際、システムが健康を損なうものであれば使用されない可能性が高いため、ある程度健康に関心を持つべきであることは理解しています。しかし、それでも、特定の人々の健康を促進する一方で他の人々の健康を犠牲にするような形で設計されることがあります。たとえば、ユーザーが特定の商品を購入する可能性を高めるように設計された場合、AI企業の(スポンサーの)経済的利益が大幅に促進される可能性がありますが、それが他の多くの人々の利益を損なう結果を招くこともあります (Strickland 2019)。

Even where conflicts of interests are eliminated, what we class as ‘evidence’ will inevitably be biased by the particular conceptions of truth that we all have. An AI designer might, for example, be biased either consciously or unconsciously by the assumption that our understanding of medicine should be based largely on scientific data derived from the study of male bodies, thereby ignoring the possibility that this science may not apply to the bodies of others. The upshot might be an AI system that performs well for males, but less well for others. Such gender bias is common both in medicine and in AI systems.

さらに、利害の衝突が排除された場合でさえ、私たちが「エビデンス」とみなすものは、私たち各々が持つ真実に関する特定の概念に偏っていることは避けられません。たとえば、AI設計者は意識的または無意識的に、「医学の理解は主に男性の身体を対象とした科学データに基づくべきだ」との前提に偏っている可能性があります。その結果、男性には優れた性能を発揮する一方、他の人々にはそうではないAIシステムが生まれるかもしれません。このようなジェンダーに基づく偏りは、医療やAIシステムの両方でよく見られる問題です。

The important thing is to separate unjustifiable from justifiable bias, as well as to avoid discarding sources of bias from cultural traditions that are different from one’s own without serious critical scrutiny. Sometimes, unjustified bias may not be able to be eliminated without causing a greater injustice. In such situations, one must try to recognise (the possibility of) bias, and try to ensure that the injustice is the lesser evil compared to another injustice (Loughlin 2008).

重要なのは、正当化できない偏りと正当化できる偏りを区別し、自分とは異なる文化的伝統からの偏りを、十分に批判的に検討することなく排除しないことです。場合によっては、正当化できない偏りを排除することが、別の大きな不正義を生む場合もあります。このような状況では、偏りの可能性を認識し、その不正義が他の不正義と比べて小さいものであることを確認する必要があります (Loughlin 2008)。

Image 2: CC BY-SA 3.0; Evidence based by Nick Youngson; Pix4free; https://pix4free.org/photo/31575/evidence-based.html

Reflection:

How would you separate evidence from falsehood?

考察の時間

エビデンスと誤情報をどのように区別しますか?

An AI system may recommend that a London bus should be red as it might be ‘trained’ on images of London buses being red. Similarly, it might recommend that Wenxin Keli should be used to treat patients with atrial fibrillation from data that shows that many patients with atrial fibrillation take Wenxin Keli. However, it is important to separate correlation from causation. The fact that two things are frequently correlated does not imply that one thing causes another. To count as evidence in health care, one must establish that taking a particular substance or receiving a particular treatment causes a particular outcome (Deckers 2023: chapter 6, particularly 6.4-6.6).

AIシステムが「ロンドンのバスは赤色であるべき」と推奨する場合、それはロンドンのバスが赤色である画像をもとに「学習」している可能性があります。同様に、AIシステムが心房細動患者に「Wenxin Keli(温心顆粒という中国でしばしば用いられている薬剤)」を使用すべきと推奨する場合、その根拠は多くの心房細動患者がこの薬を服用しているというデータかもしれません。しかし、相関関係が因果関係を示すわけではありません。ヘルスケアにおけるエビデンスとして評価されるには、特定の物質の摂取や治療が特定の結果を引き起こすことを立証しなければなりません(Deckers, 2023: 第6章、特に6.4-6.6)。

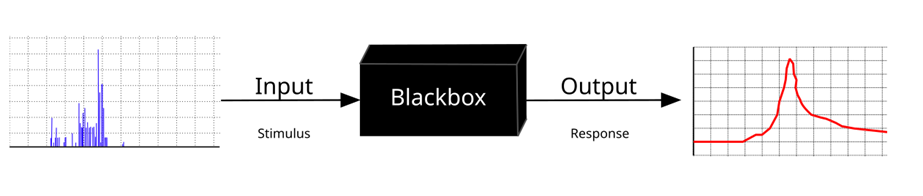

3. How to navigate the black box of AI? / AIのブラックボックス問題にどう対処するか?

Even where AI systems may be reliable, they may not be transparent. Some talk about the black box of AI to refer to this lack of transparency (Von Eschenbach 2021). Some AI systems are deliberately designed in that way as the companies that develop them may be keen to protect their intellectual property. They may not like to give away their trade secrets. Although this is understandable, health care workers are challenged with tricky dilemmas here: do they trust AI systems where it is not clear how their outputs (e.g. treatment recommendations) are produced?

AIシステムが信頼できる場合であっても、それが必ずしも透明性を持っているとは限りません。この透明性の欠如を指して、AIの「ブラックボックス」と表現することがあります(Von Eschenbach, 2021)。一部のAIシステムは、設計した企業が知的財産を保護し、自社の機密を守りたいと考えるために、意図的にこのように設計されています。このような理由は理解できるものの、ヘルスケア従事者にとっては厄介なジレンマを引き起こします。たとえば、治療の推奨など、AIシステムがどのように出力を生成しているのか不明確な場合、従事者はそのAIシステムを信頼すべきでしょうか?

Image 3: CC BY-SA 4.0; Krauss Vector: Pduive23; https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/5/5b/Blackbox3D-withGraphs.svg

Reflection:

Would you ever use an AI system if you were unclear what its recommendations were based on?

考察の時間

もしAIシステムの推奨が何に基づいているのか不明なとき、それでもあなたはそのシステムを使用しますか?

Sometimes, this lack of explainability is not due to the company wanting to hide how systems works, but due to an inherent feature of some systems, for example those that rely on ‘machine learning’. Here, AI systems are fed with huge amounts of data, and the machine ‘learns’ to find patterns in the data that may help health care workers to identify diseases or to make treatment decisions. In the UK, a TBS (‘transplant benefit score’) model is currently being used to help health care workers to make decisions about which patients to allocate organs to (Lee et al. 2023). A new AI system has been shown to be able to do a better job, at least if we class ‘better’ here in terms of organs lasting longer. However, the problem is that those who designed it do not understand how it manages to do this (Wingfield et al. 2020). A patient might ask here why they did not deserve priority over another patient in transplant decisions.

一部のAIシステムにおける説明不可能性は、企業が仕組みを隠そうとしているのではなく、「機械学習」などのシステム固有の特徴によるものです。この場合、AIシステムには膨大なデータが投入され、機械がそのデータのパターンを「学習」することで、疾病の特定や治療方針の決定に役立てます。たとえば、イギリスでは現在、TBS(臓器移植の利益スコア)モデルが、臓器をどの患者に割り当てるかを決定するために使用されています(Lee et al., 2023)。新しいAIシステムは、少なくとも臓器の生着持続期間を基準とする場合、これより優れた結果を出せることが示されています。しかし、問題は、設計者自身がそのAIシステムがどのようにその結果を出しているのか理解していない点です(Wingfield et al., 2020)。このような状況で、移植の優先順位がなぜ他の患者よりも低いのかを尋ねられた場合、患者にどのように説明するのでしょうか?

Reflection:

Reflect for a moment on what a health care worker might tell the patient in this situation?

考察の時間

このような状況で医療従事者が患者に何を伝えるべきか考えてみてください。

The health care worker would need to reply that they do not understand the output either. Rather than health care workers relying blindly on AI systems, research (e.g. randomised controlled trials) might be carried out to check whether a particular AI system might make better decisions compared to other ways in which decisions could be made. Where such trials have been carried out, a health care worker might say to a patient that they do not understand the reason behind the decision, but that a study had shown that the machine performed better than a team of people deciding without the help of AI. They would also need to explain to the patient what criterion or criteria had been used to define ‘better’. It might mean, for example, either that organs last longer or that those who receive the transplanted organs suffer fewer side-effects.

医療従事者は、この出力の理由を理解していないと答える必要があるかもしれません。しかし、医療従事者がAIシステムを盲目的に頼るのではなく、ランダム化比較試験などの研究を実施することで、特定のAIシステムが他の方法と比較してより良い決定を下すかどうかを確認することができます。このような試験が実施された場合、医療従事者は患者に対し、決定の背後にある理由を理解していないが、研究によりそのAIシステムが従来の方法よりも優れていることが示されたと説明することができます。また、患者に対し、「より優れている」と判断された基準についても説明する必要があります。たとえば、臓器の生着持続期間が長いか、移植を受けた患者の副作用がより少ないかといった基準です。

4. How to use AI data responsibly? / AIデータをどのように責任を持って使用するか?

By using AI systems, health care workers are also able to gather a lot more patient data than they used to be able to, to analyse it better, and to store it more easily for a long period of time. The handling of AI data comes with significant moral risks. These include inadvertent data loss, deliberate sharing of data, and the inappropriate use of data for research. Even if confidentiality is an important value, it may need to be traded off with other values, for example beneficence (well-being). The classical model of consent is that patients should provide consent for specific therapeutic goals or research projects. This might be questioned as many ascribe value to the fact that AI systems can pool data gathered from multiple sources, store it with greater ease, and for a much longer time. Data that may not be useful today may become useful in the future. The usage of data for as yet unspecified research projects (a long time) in the future would be problematic if we hold on to the idea that patients should be allowed to consent only for specified research projects.

AIシステムを使用することにより、医療従事者はこれまで以上に多くの患者データを収集し、それをより詳細に分析し、長期間簡単に保存することが可能になります。しかし、AIデータの取り扱いには重大な倫理的リスクが伴います。これには、データの偶発的な損失、故意のデータ共有、研究へのデータの不適切な使用などが含まれます。機密保持は重要な価値ですが、しばしば他の価値、たとえば「善行」(患者のウェルビーイング)との間でバランスを取る必要があります。従来の同意モデルでは、患者は特定の治療目的や研究プロジェクトに同意を与えるべきとされています。しかし、AIシステムがさまざまな情報源から収集されたデータを統合し、それをより容易に、また長期間保存できる点に価値を見出す人も多くいます。現在の段階では役立たないデータが、将来においては有益になる可能性があるのです。今後の未特定の研究プロジェクトのために長期間データを使用することは、「患者は特定の研究プロジェクトにのみ同意すべき」という考え方に基づけば問題となるかもしれません。

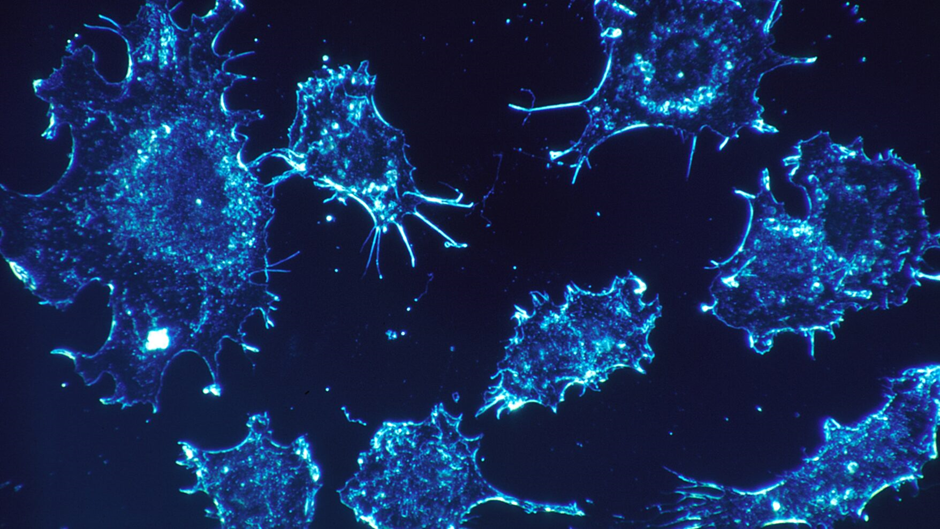

Imagine that an AI system helps you to find out that a particular patient is at greater risk of developing cancer compared to the average patient, for example through the AI system analysing particular images of the patient’s tissues and finding that some are pre-cancerous. The patient does not know about this.

次のような状況を想像してください。AIシステムが患者の組織の特定の画像を分析し、一部が前がん状態であることを発見することで、ある患者が平均的な患者よりもがん発生のリスクが高まっていると判断したとします。しかし、この情報が患者には知らされないとしたらどうでしょう。

Image 4: CC0 1.0; cancer cells as viewed under a microscope; rawpixel.com

Reflection:

Reflect for a moment on what you might do with this newly acquired information.

考察の時間

この新たに得られた情報をどのように扱うべきか考えてみてください。

This finding might be highly relevant for the patient if the patient could be screened for cancer more regularly because of this finding, and if early detection of cancer might help in the treatment. This is not always guaranteed. For example, thanks to recent technological breakthroughs in AI, more patients can be diagnosed with thyroid cancer. However, in spite of this, prognoses for patients suffering from thyroid cancer have not improved significantly (Ho et al. 2015; van Deen et al. 2023). Moreover, some cancers can resolve without any treatment, a phenomenon known as spontaneous remission (Radha and Lopus 2021). While scientists think that this is rare, if technology to diagnose cancer is improved, more cancers that might resolve without any treatment may be identified. Before health care workers decide to share information with patients, it is therefore important to assess whether it might be better for the patient not to receive information, particularly when it might make them anxious.

この発見は、患者にとって非常に重要である可能性があります。たとえば、この情報をもとに患者が定期的にがんスクリーニングを受けることで、早期発見が治療に役立つ場合があります。ただし、それが必ずしも保証されるわけではありません。たとえば、AIの最近の技術的進歩により、より多くの患者が甲状腺がんと診断されるようになりました。しかし、それにもかかわらず、甲状腺がん患者の予後は劇的には改善していません(Ho et al., 2015; van Deen et al., 2023)。さらに、一部のがんは治療なしに自然と消失する場合もあります。この現象は「自然寛解」として知られています(Radha and Lopus, 2021)。科学者たちはこれが稀であると考えていますが、がん診断技術が向上することで、治療を必要としないがんがより多く発見されるかもしれません。そのため、医療従事者が患者と情報を共有する前に、その情報が患者にとって本当に有益かどうかを慎重に評価することが重要です。特に、それが患者を不安にさせる可能性がある場合にはなおさらです。

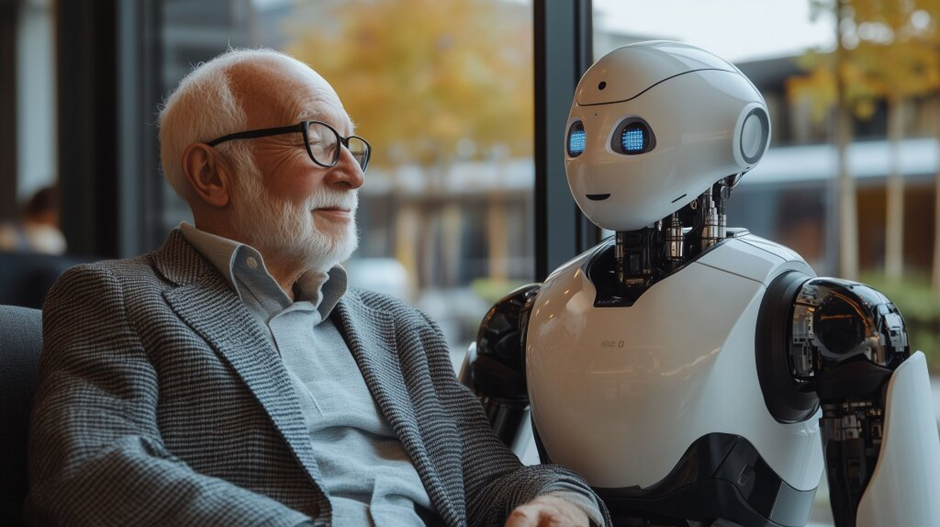

5. What are the ethical issues related to the use of carebots? / ケアボット(介護ロボット)の使用に関する倫理的問題は何か?

In a rapidly ageing society, for example in Japan, relatively few young people must care for an increasing number of older people. Care robots (or ‘carebots’) have been designed to take over some of this care work (Robson 2019). This raises some dilemmas.

急速に高齢化が進む社会、たとえば日本では、比較的少ない若者が増加する高齢者人口を支えなければなりません。このような状況で、ケアロボット(または「ケアボット」)は、一部の介護業務を代替する目的で設計されています(Robson, 2019)。しかし、これによりいくつかのジレンマが生じます。

Reflection:

Reflect on the following questions:

- Are carebots able to provide good care?

- Might there be situations where they cannot do so?

- Might the extensive use of carebots in the (health) care sector lead to problematic ideas about what human care should consist of?

考察の時間

以下の問いについて考えてみてください。

- ケアボットは良いケアを提供することができるでしょうか?

- どのような状況ではそれができない可能性があるでしょうか?

- ヘルスケア分野でケアボットを広く使用することが、人間によるケアの本質に関する問題を引き起こす可能性はありますか?

Image 5: CC-BY 2.0; Marco Verch; Älterer Mann sitzt neben humanoidem Roboter in einem Café; https://ccnull.de/index.php/foto/aelterer-mann-sitzt-neben-humanoidem-roboter-in-einem-cafe/1102624

Carebots may be able to provide good care, but it does not seem appropriate to hold the view that they could replace the care that human beings can provide. To lift someone who is very heavy in and out of bed, for example, a carebot might be able to do a very good job. Indeed, it might be able to do a much better job than could be done by a human carer where the latter would lack the physical strength possessed by the AI device. However, a carebot would not seem to be able to provide human care. How could essential attributes of care, such as compassion, love, and tenderness, be shown by an AI device? An AI system might be able to simulate these traits, which may lead the human being who is being cared for to think that they receive real care. Potentially, this might lead to misconceptions about what ‘AI care’ is and about what ‘human care’ is.

ケアボットが良いケアを提供できる場合もありますが、人間が提供できるケアを完全に代替できると考えるのは適切ではないように思われます。たとえば、非常に重い人をベッドから持ち上げて移動させる場合、ケアボットは非常に良い仕事をするかもしれません。実際、肉体的な力が不足している人間の介護者よりも優れた結果を出す場合もあります。しかし、ケアボットが人間のケアを提供することは難しいでしょう。ケアの本質的な要素である「思いやり」「愛情」「優しさ」をAIデバイスが示すことはどうすれば可能でしょうか?AIシステムがこれらの特性をシミュレーションすることはできるかもしれません。それにより介護を受ける人が本物のケアを受けていると感じることさえあるでしょう。しかしその結果、「AIによるケア」と「人間によるケア」が何であるかについて誤解を生じさせる可能性が出てきます。

6. Is the use of AI for health care sustainable? / ヘルスケア向けAIの使用は持続可能か?

The implementation of large amounts of data into AI systems also raises other issues, for example related to the notion of sustainability. This notion has both a social and an ecological component.

膨大な量のデータをAIシステムに取り込むことは、社会的および環境的な観点から「持続可能性」という概念に関連する問題を引き起こします。

Socially, the question must be asked whether current work that is being carried out in the AI sector can and, more importantly, ought to be sustained. The development of ‘machine learning’, for example, relies on a large number of data being fed into computer systems, which requires a lot of time, and may not be the most interesting type of work. It may also not be paid well, raising the question whether some people are being exploited to develop AI and what ought to be done about this. Heilinger et al. (2024, p. 206) comment, for example that ‘the financial gains made from AI-based systems are distributed extremely unequally, as can be shown by comparing the annual financial gains of, say, Amazon’s CEO on the one extreme end and the underpaid labourers working under dangerous and exploitative conditions in the cobalt mines on the other extreme end’.

社会的に生じてくる問いは、現在AI分野で行われている作業が継続可能かというもの、さらにもっと重要なものとして、そもそも継続されるべきかという問いです。たとえば、「機械学習」の開発では、大量のデータをコンピュータシステムに入力する必要があり、多くの時間が必要です。この作業は最も興味深い種類の仕事とは言えないかもしれず、十分な賃金が支払われない場合もあります。そのため、AIの開発において一部の人々が搾取されている可能性があり、この問題に対してどのような対策を講じるべきかが問われます。Heilingerら(2024)は次のようにコメントしています。「AIベースのシステムから得られる経済的利益は極めて不平等に分配されており、その例としてAmazonのCEOが得る年間収益と、危険で搾取的な条件で働くコバルト鉱山の労働者を比較することができる。」

Ecologically, the development of AI also raises questions as vast natural resources are used to build hardware. This, as well as the development and use of software, requires energy, where much of this energy is generated by the use of dwindling natural resources, emitting toxic and dangerous gases in the process (Bolón-Canedo et al. 2024).

環境的には、AIの開発も大きな課題を引き起こします。たとえば、ハードウェアの製造には膨大な天然資源が必要です。さらに、ソフトウェアの開発および使用もエネルギーを必要とし、多くのエネルギーが有限の天然資源を利用して生成されており、その過程で有毒で危険なガスが放出されています(Bolón-Canedoら、2024)。

Image 6: CC BY-NC-SA 4.0; Photo by Etienne Girardet on Unsplash; https://unsplash.com/?utm_source=medium&utm_medium=referral

Reflection:

What do you think should be done to ensure that the development and use of AI systems is sustainable?

考察の時間

AIシステムの開発と使用が持続可能であることを保証するために、どのような対策が必要だと思いますか?

One thing that could and should be done is to try to make AI systems more energy-efficient. However, this does not guarantee that the development of AI systems will become more sustainable. In this regard, Wu et al. (2022) point out that ‘despite the significant operational power footprint reduction, we continue to see the overall electricity demand for AI to increase over time — an example of Jevon’s Paradox, where efficiency improvement stimulates additional novel AI use cases’. Similarly, Heilinger et al. (2024) make the point that AI systems in general are unlikely to be sustainable at the present time as long as the socio-economic situation is one that favours permanent economic growth.

ひとつ可能な対策は、AIシステムをよりエネルギー効率の良いものにすることです。しかし、これによってAIシステムの開発がより持続可能になることは保証されません。この点について、Wuら(2022)は次のように指摘しています。「運用のエネルギー消費が大幅に削減されたにもかかわらず、AIの電力需要は時間とともに増加し続けている。これは効率の向上が新たなAIの利用場面を惹起するというJevonの逆説の一例である。」同様に、Heilingerら(2024)は、現代の社会経済状況が恒久的な経済成長を追求する限り、AIシステムが持続可能になる可能性は低いと指摘しています。

7. Does AI change human self-understandings or identities, and does it do so for better and/or for worse? / AIは人間の自己認識やアイデンティティをどのように変えるのか、そしてそれは良い変化なのか悪い変化なのか?

In spite of this lack of sustainability, Heilinger et al. (2024, p. 210) also claim that ‘AI is likely to increasingly influence and shape human lives in the future’, which raises the question whether it might change human self-understandings or even human nature, and whether it might do so for better or for worse.

持続可能性の欠如にもかかわらず、Heilingerら(2024)は、「AIは今後ますます人間の生活に影響を与え、社会を形成するようになる可能性が高い」と主張しています。これにより、AIが人間の自己認識やさらには人間の本質そのものを変えるかもしれないという問いが生じます。そして、これが良い変化なのか悪い変化なのかについても議論が必要です。

Reflection:

Reflect for a moment on how the self-understandings or identities/characters of health care workers and patients who use AI might differ from those who do not use AI systems at all.

考察の時間

AIを使用する医療従事者や患者の自己認識やアイデンティティが、AIを全く使用しない場合とどのように異なる可能性があるか考えてみてください。

While it is hard to say how AI might alter the self-understandings or characters of health care workers and patients, it is likely that the use of AI systems alters people in profound ways. For example, the time that a doctor spends looking at a screen competes with the time that the doctor communicates with patients, which may affect the self-understandings of both. A patient who uses the internet to look up health-related information may also be transformed by what they read, which may influence how they approach a doctor, for example by enabling them to ask more relevant questions. A patient with a prosthetic limb that incorporates features of an AI system may also alter their understandings of themselves as their body is, arguably, enhanced by the prosthetic, which enables the person to move better.

AIが医療従事者や患者の自己認識や特性にどのような影響を与えるかを断言するのは難しいですが、AIシステムの使用が人々を大きく、深く変化させる可能性は高いでしょう。たとえば、医師が患者とコミュニケーションを取る時間がスクリーンを見つめる時間と競合する場合、これが医師と患者の双方の自己認識に影響を及ぼすかもしれません。他方で、患者がインターネットで健康に関する情報を調べることで、その知識によって自身の考え方や態度が変化し、医師に対してより的確な質問を行えるようになる可能性もあります。さらに、AIシステムを搭載した義肢を使用する患者が、自分の身体が補完され、動きやすくなったと認識することで、自己認識が変わるかもしれません。

A more profound change might be brought about by a system that detects levels of dopamine in the body and that administers medication to boost dopamine levels in Parkinson’s patients, who may go on to live with fewer symptoms of the disease because of it. An even more significant change might be brought about by an AI system that would detect the presence of particular (quantities of) hormones in the body, for example oxytocin, and release chemicals to restore any imbalances at appropriate times to facilitate pro-social behaviour. The identity of a person who may be quite anti-social might be altered quite significantly if they suddenly become more pro-social because of it.

さらに深い変化は、ドーパミンの量を検出し、それを補う薬剤を投与するAIシステムを使用する場合に見られるかもしれません。このようなシステムは、パーキンソン病患者が症状を軽減して生活することを可能にします。また、特定のホルモン(たとえばオキシトシン)の存在量を検出し、不均衡を修正する化学物質を適切なタイミングで放出するAIシステムがあれば、社会的行動を促進することができるかもしれません。反社会的な傾向があった人が、これによって急に社会的になる場合、その人のアイデンティティは非常に大きく変化する可能性があります。

Image 7: CC0; Low Section of Person with Prosthetic Leg; https://www.pexels.com/photo/low-section-of-person-with-prosthetic-leg-9623428/

AI is not the only technology that can profoundly impact human identity. For most of evolutionary history, human beings developed in environments that did not provide artificial light, for example. This raises the question whether we are adapted to living in such luminous environments, even if such environments have also provided significant benefits. Like artificial light, AI is likely to have transformed human beings significantly. This raises other interesting questions.

AIは人間のアイデンティティに深く影響を与える唯一の技術ではありません。たとえば、人類の進化のほとんどの期間、人工的な光源のない環境で育まれてきました。このことは、人工的な光に適応しているのかどうかという疑問を投げかけますが、人工的な光が多くの恩恵をもたらしていることも事実です。同様に、AIは人類を大きく変化させる可能性が高い技術であり、他にも興味深い疑問を提起します。

Reflection:

Reflect for a moment on these questions:

- What is artificial?

- How are different artificial things connected to each other?

- How is what is artificial related to what is moral?

You might explore this theme further in Deckers 2023: chapter 8.3.

考察の時間

以下の質問について考えてみてください。

- 何が「人工的」であると言えるのでしょうか?

- さまざまな人工物同士はどのように関連しているのでしょうか?

- 人工的なものと道徳的なものはどのように関係しているのでしょうか?

このテーマについては、Deckers(2023)の第8章3節でさらに詳しく探求することができます。

8. Do people produce conscious entities when they create AI systems? / AIシステムを作成する際、人々は意識を持つ存在を生み出しているのか?

Another interesting question is whether advances in AI technology might alter the AI systems that are being designed in very significant ways. Some scholars suggest that, at some point in the future, AI systems might perhaps become conscious or have experiences (Llorca Albareda et al. 2024). As consciousness/experience has been associated with (greater) moral status, AI systems might then perhaps no longer be regarded as objects that one can manipulate freely (objects that should be valued for their instrumental value), but as sentient entities that must be regarded as having a higher moral status because of it (that should be valued as ‘moral patients’ for their intrinsic value) (Deckers 2023: chapter 1.4).

AI技術の進歩により、AIシステムが非常に大きな変化を遂げる可能性があります。一部の学者は、将来的にAIシステムが意識を持ったり、経験を有する可能性があると示唆しています(Llorca Albaredaら、2024)。意識や経験は(より高い)道徳的地位と結びついているため、その場合AIシステムは、自由に操作できる物(道具的価値を持つもの)ではなく、意識を持つ存在としての道徳的価値を持つ「道徳的主体」としてみなされる可能性があります(Deckers, 2023: 第1章4節)。

Image 8: CC BY-ND 4.0; commander data star trek emoji | AI Emoji Generator; https://emojis.sh/

A different question is whether they might even be subjects with moral agency, or moral agents. Jecker and Nakazawa (2022, p. 770) remark that ‘the Japanese saying, Yoyorozu-no-Kami (8 million gods), expresses the idea that the Japanese see gods in everything’, and they suggest that Japanese people may be more open compared to many others to the idea of some AI systems being animated. Imagine an AI system that looks a great deal like a real doctor, for example a social robot with human-like features (for example, like Lieutenant Commander Data, an android or humanoid robot featuring in the Star Trek television series), such as a voice that simulates a human voice and a shape that resembles that of a human being. Some patients may come to regard such an AI machine as a real doctor, but would it be a real doctor (Llorca Albareda et al. 2024)?

一方で、それらが道徳的主体ではなく、むしろ道徳的責任を負う「道徳的エージェント」になり得るかどうかという別の問いも存在します。Jecker and Nakazawa(2022)は、「日本の言葉である『八百万の神(やおよろずのかみ)』は、あらゆるものに神性が宿るという考えを表しており、日本人は多くの他国民よりもAIシステムを生命的存在として捉える可能性がある」と述べています。たとえば、人間に似た特徴(たとえば人間の声に似た音声や、人間の形状を模倣した外観)を持つ社会的ロボットが登場すれば、患者の中にはこのようなAI機械を本物の医師としてみなす人もいるかもしれません。しかし、それは本当に「医師」と言えるのでしょうか?(Llorca Albaredaら、2024)

Reflection:

Reflect for a moment on whether an AI machine might ever be a moral decision-maker? If so, who would be to blame if a bad decision was made: the AI system (now regarded as an AI doctor), the company that designed it, the person who decides to use it, or some combination of some of these?

考察の時間

AI機械が道徳的な意思決定を下すことが可能になるとしたら、その場合、誤った決定が下されたときに誰が責任を負うべきでしょうか?AIシステム(AI医師とみなされる存在)、それを設計した企業、それを使用した人、またはこれらの要素の組み合わせでしょうか?

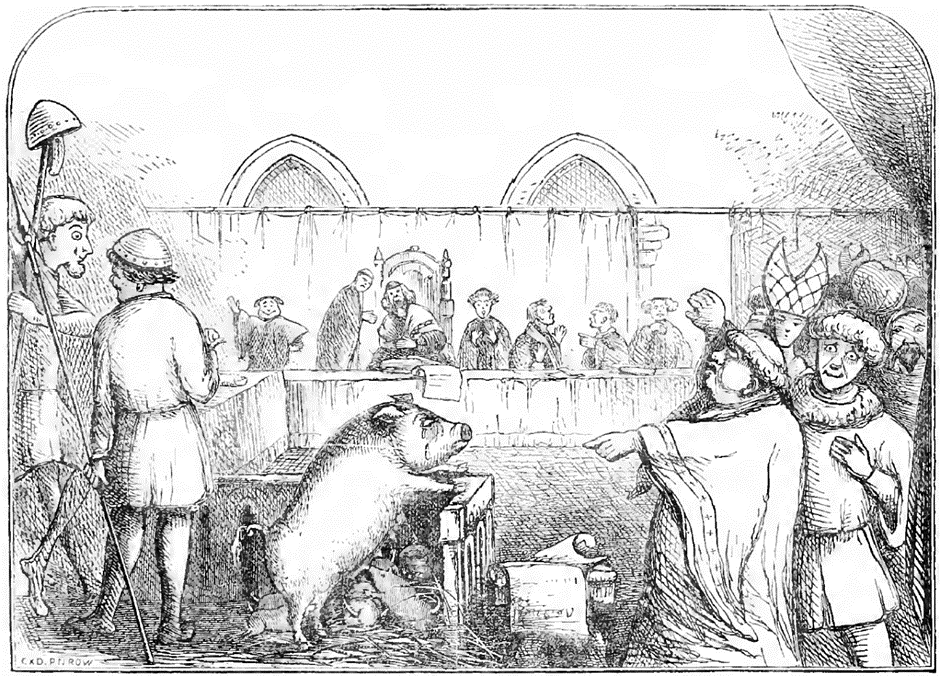

Some nonhuman animals have been put on trial in the past.

過去には、一部の動物(人間ではない)が裁判にかけられた事例もあります。

Image 9: in public domain, from Chambers (1864), depicting a sow and her piglets being tried for the murder of a child. The trial is held to have taken place in 1457: the mother was found guilty and the piglets were acquitted.

Might the time now have come for some AI systems to carry some blame? A lot of philosophical work is currently being done to try to address whether some AI systems might be moral patients or moral agents. The important message for (training) health carers might be this one: the burden of proof should be on those who claim that AI systems might carry (part of) the blame. There does not seem to be sufficient evidence to suggest that human beings should be exculpated from any wrong decisions that they may make with the use of AI systems.

もしかすると、現在ではAIシステムに一部の責任を負わせる時代が来たのでしょうか?現在、多くの哲学的研究が「AIシステムが道徳的主体や道徳的エージェントとなる可能性」について検討しています。医療従事者(および今後医療従事者になる皆さん)への重要なメッセージは以下の通りです。責任がAIシステムにあると主張する者に立証責任があるべきです。AIシステムの使用による誤った決定から人間が責任を免れるべきだと示唆する十分な証拠は現時点ではありません。

AI systems cannot be blamed as they are not moral agents. Takahiro Nakajima (2024) writes rightly that ‘AI does not understand the “meaning” of the character strings it presents at all’ and that ‘chatting with AI is ultimately a monologue, not a dialogue’. However, one should be mindful that some AI systems designers may try to dodge responsibility for their creations by blaming the systems, rather than those who produced them.

AIシステムは道徳的主体ではないため責任を負うことはできません。中島隆博(2024)は、「AIは提示する文字列の『意味』を全く理解していない」「AIとの対話は最終的には独り言であり、対話ではない」と的確に指摘しています。しかし、一部のAI設計者が、自らの責任を回避するためにAIシステムに責任を押し付けることがないよう注意する必要があります。

9. Conclusion / まとめ

This learning resource was designed to stimulate ethical discussion of how health care might be improved and undermined by the development of artificial intelligence (AI) and how AI systems ought to be designed and used to promote health care. Topics included how to ensure that AI for health care is evidence-based, how one might navigate the black box of AI, how one might use AI data responsibly, what the ethical issues are related to the use of carebots, whether the use of AI for health care is sustainable and what should be done to ensure social and ecological sustainability, as well as whether AI changes us and whether we change the entities used to create AI systems. Health care workers and patients may wonder about many other topics related to AI. However, the main problems and opportunities associated with the use of AI systems in health care may be captured in this resource.

この学習教材は、ヘルスケアを向上させると同時に損なう可能性のある人工知能(AI)の発展について、またAIシステムがどのように設計され、ヘルスケアの促進のために使用されるべきかについての倫理的議論を喚起することを目的としていました。具体的には、以下のようなトピックを扱いました。

- ヘルスケア向けAIがエビデンスに基づいていることをどのように保証するか?

- AIのブラックボックス問題にどのように対処するか?

- AIデータをどのように責任を持って使用するか?

- ケアボット(介護ロボット)の使用に関する倫理的問題は何か?

- ヘルスケア向けAIの使用は持続可能か?その社会的および環境的持続可能性をどのように保証するか?

- AIは私たちをどのように変えるのか、そして私たちはAIシステムの作成に使用される存在をどのように変えるのか?

医療従事者や患者は、AIに関連する他の多くのトピックについても疑問を抱くかもしれません。しかし、ヘルスケアにおけるAIシステムの使用に伴う主要な問題や機会は、この教材で大部分を網羅しています。

Exercises/Group Discussion Questions / 演習・グループディスカッション

The following list of questions can be used to stimulate personal reflection, classroom discussion or essay writing:

1. What would you do to check whether an AI system that is being used in health care might provide good information?

2. Would you ever use an AI system in health care if you did not understand what the outputs of the system were based on? If so, what would be the conditions for using it?

3. What should health care workers and researchers do to ensure that they use AI data responsibly?

4. Would you ever condone the use of carebots? If so, what would be the conditions?

5. What should designers and users of AI systems in health care, as well as regulators, do to ensure that the use of such systems is sustainable?

6. How might the self-understandings or the nature of health care workers and patients be affected by the use of AI systems in health care?

7. Do you think that people produce conscious entities when they create AI systems, and what might be the moral implications of creating conscious AI systems?

このリストは、個人ワーク、授業でのグループディスカッション、レポート作成のに応用することができます。

- ヘルスケアに使用されるAIシステムが正確な情報を提供することを確認するために、どのような手段を講じますか?

- AIシステムの出力の根拠が不明な場合でも、それをヘルスケアで使用することに賛成しますか?その場合、どのような条件が必要ですか?

- 医療従事者や研究者がAIデータを責任を持って使用するためには、何をすべきですか?

- ケアボットの使用を容認しますか?容認する場合、その条件は何ですか?

- ヘルスケア向けAIシステムの設計者、ユーザー、そして規制当局は、その使用が持続可能であることをどのように保証すべきですか?

- ヘルスケア従事者や患者の自己認識や性質は、AIシステムの使用によってどのように影響を受ける可能性がありますか?

- AIシステムを作成する際、人々は意識を持つ存在を生み出していると思いますか?その場合、意識を持つAIシステムを作成することの道徳的な意味は何でしょうか?

References / 参考文献

Bolón-Canedo, V., Morán-Fernández, L., Cancela, B. and Alonso-Betanzos, A., 2024. A review of green artificial intelligence: Towards a more sustainable future. Neurocomputing, 599 (September), 1-10.

Chambers, R. 1864. The Book of Days: A Miscellany of Popular Antiquities in Connection with the Calendar, Including Anecdote, Biography, & History, Curiosities of Literature and Oddities of Human Life and Character. W. & R. Chambers.

Deckers, J. 2023. Fundamentals of Critical Thinking in Health Care Ethics and Law. Ghent: Owl Press.

Heilinger, J.C., Kempt, H. and Nagel, S., 2024. Beware of sustainable AI! Uses and abuses of a worthy goal. AI and Ethics, 4(2), 201-212.

Ho, A.S., Davies, L., Nixon, I.J., Palmer, F.L., Wang, L.Y., Patel, S.G., Ganly, I., Wong, R.J., Tuttle, R.M., and L.G. Morris., 2015. Increasing diagnosis of subclinical thyroid cancers leads to spurious improvements in survival rates. Cancer, 121(11): 1793-1799.

Jecker, N.S. and Nakazawa, E., 2022. Bridging east-west differences in ethics guidance for AI and robotics. AI, 3(3), 764-777.

Llorca Albareda, J., García, P. and Lara, F., 2024. The Moral Status of AI Entities. In Lara, F. and Deckers, J. (eds). 2024. Ethics of Artificial Intelligence, Cham: Springer, pp. 59-83.

Lee, E.G., Perini, M.V., Makalic, E., Oniscu, G.C. and Fink, M.A., 2023. External validation of the United Kingdom transplant benefit score in Australia and New Zealand. Progress in Transplantation, 33(1), 25-33.

Loughlin, M., 2008. Reason, reality and objectivity–shared dogmas and distortions in the way both ‘scientistic’and ‘postmodern’commentators frame the EBM debate. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 14(5), 665-671.

Moyano-Fernández, C. and Rueda, J., 2024. AI, Sustainability, and Environmental Ethics. In Lara, F. and Deckers, J. (eds). 2024. Ethics of Artificial Intelligence, Cham: Springer, pp. 219-236.

Nakajima, T., 2024. Listening to the Daoing in the Morning. Paper presented at the Kyoto Institute of Philosophy, November 2, 2024.

Radha, G. and Lopus, M., 2021. The spontaneous remission of cancer: Current insights and therapeutic significance. Translational Oncology, 14(9), p.101166.

Robson, A., 2019. Intelligent machines, care work and the nature of practical reasoning. Nursing ethics, 26(7-8), 1906-1916.

Strickland, E., 2019. IBM Watson, heal thyself: How IBM overpromised and underdelivered on AI health care. IEEE Spectrum, 56(4), 24-31.

van Deen, W.K., Spiegel, B.M. and Ho, A.S., 2023. A narrative review of decision aids for low-risk thyroid cancer. Ann Thyroid, 8(3), 1-8.

Von Eschenbach, W.J., 2021. Transparency and the black box problem: Why we do not trust AI. Philosophy & Technology, 34(4), 1607-1622.

Wingfield, L.R., Ceresa, C., Thorogood, S., Fleuriot, J. and S. Knight. 2020. Using artificial intelligence for predicting survival of individual grafts in liver transplantation: a systematic review. Liver Transplantation, 26(7), 922-934.

Wu, C.J., Raghavendra, R., Gupta, U., Acun, B., Ardalani, N., Maeng, K., Chang, G., Aga, F., Huang, J., Bai, C. and Gschwind, M., 2022. Sustainable ai: Environmental implications, challenges and opportunities. Proceedings of Machine Learning and Systems, 4, 795-813.