Social mobility is a peculiarly British preoccupation, while in the US aspiration is associated with economic opportunity, social class has been defined by occupation. Mobility is about not being tied to the class of your birth, i.e. your father’s, but being able to have control over your occupational outcome, relative to the opportunities of others. Grammar schools are often cited as offering the life chances which a fair society should offer, which the state education system is not seen to be delivering, that working class children with ability could attain middle class roles.

There are several anachronistic factors in the foregoing: the gendered pattern of employment status; the hierarchical structure of occupational classifications; the singularly upward interpretation of social mobility; and the idea that grammar schools support the working class. Our society has changed over decades to be more middle class and less industrial, with women aspiring to similar status as men, families where both parents work in high status roles and are concerned their children consolidate their social status.

Grammar schools were conceived in a social structure where most people had working backgrounds, and there were predicted to be shortages of educated people to take up highly educated, scientific, professional and supervisory roles. Few people went to university at all and there was greater expansion planned meaning that there was plenty of space for upward mobility without many people coming the reverse direction. People from working class backgrounds could attribute their success to the life chances offered by a grammar school education which they felt fortunate to have offered.

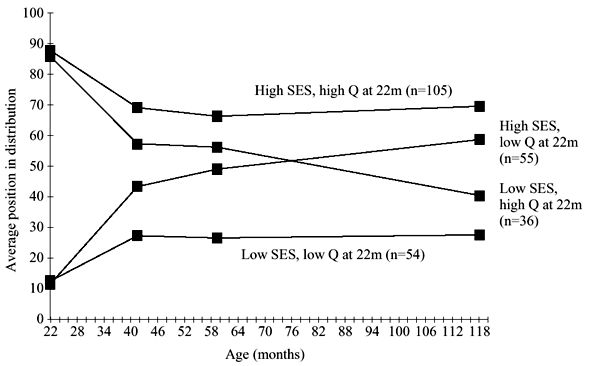

The graph shows four lines, representing cross classification of rich and poor, smart and dull, as they develop over their childhood, using data from children born in 1970. The groups are identified early on and then their average score on tests is marked to form time series, with the low-low and high-high groups being extreme as might be expected. But what focused the attention of everyone was that the other two lines crossed over, smart poor kids were overtaken by dull rich kids in middle childhood, and you could read off an age when this occurred from the graph.

The graph shows four lines, representing cross classification of rich and poor, smart and dull, as they develop over their childhood, using data from children born in 1970. The groups are identified early on and then their average score on tests is marked to form time series, with the low-low and high-high groups being extreme as might be expected. But what focused the attention of everyone was that the other two lines crossed over, smart poor kids were overtaken by dull rich kids in middle childhood, and you could read off an age when this occurred from the graph.