James Law (Newcastle University)

It was not so very long ago that Prime Minister David Cameron was extolling the need to think about a person’s Life Chances. The idea as indicated above was originally attributed to the work of German sociologist Max Weber but was really given focus in Johnson and Kossykh 2008 review Early years, life chances and equality and Frank Field’s report The Foundation Years: preventing poor children becoming poor adults.

The story was that poverty was no longer the principal driver of social inequalities but that the opportunities an individual had and then took were key to improving the lot of more disadvantaged people in society. This seemed to be especially relevant for children whose life chances had been curtailed by virtue of circumstances completely outside their control. A Life Chances strategy was promised and due to be released at the time of the Brexit vote. It was postponed, Prime Minister Cameron resigned and, life chances, along with much of the Conservative party manifesto, appeared to be kicked into the proverbial long grass. The issues remained the same, of course, but the politics had changed. Continue reading

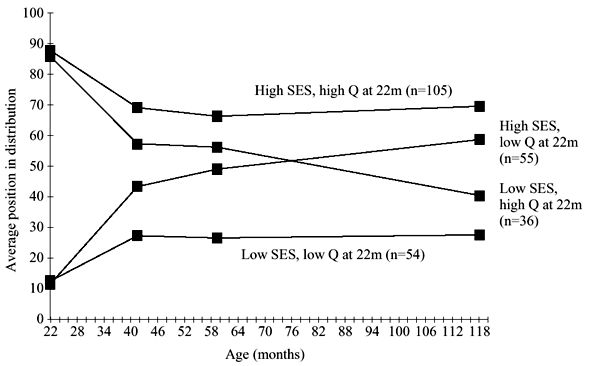

The graph shows four lines, representing cross classification of rich and poor, smart and dull, as they develop over their childhood, using data from children born in 1970. The groups are identified early on and then their average score on tests is marked to form time series, with the low-low and high-high groups being extreme as might be expected. But what focused the attention of everyone was that the other two lines crossed over, smart poor kids were overtaken by dull rich kids in middle childhood, and you could read off an age when this occurred from the graph.

The graph shows four lines, representing cross classification of rich and poor, smart and dull, as they develop over their childhood, using data from children born in 1970. The groups are identified early on and then their average score on tests is marked to form time series, with the low-low and high-high groups being extreme as might be expected. But what focused the attention of everyone was that the other two lines crossed over, smart poor kids were overtaken by dull rich kids in middle childhood, and you could read off an age when this occurred from the graph.